A HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE

ou Une Mémoire de l’Holocauste

Esther, and her husband, Maurice Korjenewski

Manicha Komar, mother of Esther Korjenewski

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

When I was 12, in the early 1960s, a couple years before the word “Vietnam” entered the American lexicon and psyche for our generation, our TV was flooded, thanks to me, with TV series about World War II. Combat, starring Jewish actor Vic Morrow (née Victor Morozoff), and Gallant Men, starring Ric Jason, were two of the shows I watched religiously. The great documentary series Victory at Sea was another. My late father, a veteran of the Army Air Corps, who served in the South Pacific during World War II, often watched them with me, but I cannot recall his words.

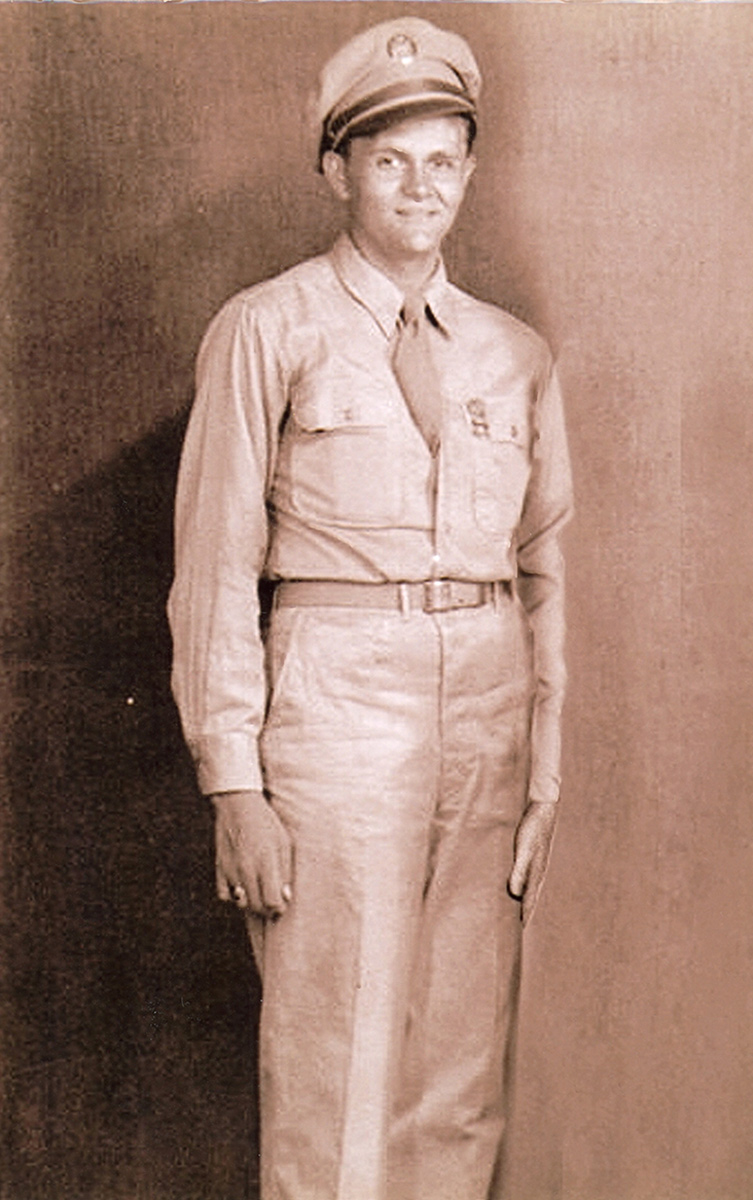

The author's father Corporal Jerry Yablonka, US Army Air Corps Radioman, South Pacific Theatre during World War II.

My late mother, on the other hand, as soon as I channel-flipped to watch one of these shows, would get up from the couch, walk into my folks’ bedroom, and quietly close the door. I never understood why until my father reminded me about the fact that the grandfather for whom I am named perished at Auschwitz. Today I understand more and am able to write about what my grandmother, mother, and aunt endured.

Because my mother was silent most of her life about what she and other members of my family went through, much of what I know, I learned from my typically talkative grandmother.

The author's grandmother, Esther, father, Jerry, and mother, Gabrielle

This, then, is what I know:

My Mother, Gabrielle, Aunt Madeleine, and their mother Esther, my grandmother, were, for a time, protected by Monsieur Charles Pacôme, a former Olympian and well-known Catholic lawyer in Lille, in the north of France.

If you’ve read or know of the book The Diary of Anne Frank, then you know how the three were protected. Ironically, Monsieur was so well known in Lille that he often entertained Nazi officers in his home.

One day, my semitic-looking Aunt Madeleine, then a young girl of 8, perhaps 9, was out playing on the road outside of Monsieur Pacôme’s house when a Gestapo officer driving down the road pulled over and began to question her. Monsieur, seeing this, ran outside and yelled at the Gestapo,”Qu’est-ce que tu fais en train de parler à ma fille?” (“What are you doing talking to my daughter?”). The Gestapo apologized and drove off.

Charles Pacôme

This is what the Worldwide Web has taught me about Monsieur Pacôme:

“Charles Pacôme was particularly successful at the Olympics. After winning the silver medal in 1928, he added a gold medal in 1932, both in lightweight freestyle [wrestling]. His only other international medal came at the 1931 European Championship with a bronze in welterweight freestyle. He was a lawyer, but he also attended the conservatory in Lille and won several prizes as a violinist.”

The latter fact would confirm a story my mother did tell me once about how he had played his violin for Nazi officers in his home. I can only wonder whether he did so while my family was being hidden inside his house at the very same time.

I wish to God that I had asked Monsieur Pacôme that question when I met him, his wife, and children in Lille in 1978. Far more important than that, though, was the fact that, before he died, I got the chance to tell him “Merci pour ma vie!” (“Thank you for my life!”).

But Monsieur Pacôme’s bravery did not always keep my family safe. At a point when my grandfather was still with them, the four were rounded up and forced into a Vichy camp outside of Paris called Drancy. There were other Vichy camps, too, but my mother never enumerated on them.

I do know that at one point, they escaped from one of them. As they were escaping, a Nazi came walking briskly toward them. My mother and aunt started to dart away, but my grandfather, Maurice, told them, “Ne cours pas!” (“Don’t run!”).

They didn’t. The Nazi passed them by.

Besides Monsieur Pacôme, my grandmother was, undoubtedly, the bravest person I have ever known. She showed her bravery countless times during World War II.

The author's aunt, Madeleine, grandmother, Esther, and mother, Gabrielle after World War II.

Once, when she was on a street car in Lille with my mother and aunt, a Nazi boarded and demanded to see all the passengers’ papers. My grandmother had fortuitously obtained false identity papers for herself and her daughters, possibly through Monsieur Pacôme, but I can’t be certain, with the very French name DuPont. But that alone would not have saved them from being arrested because, while my mother and aunt were born in Belgium, raised in France, and, therefore, spoke unaccented French fluently, my grandmother was born in Poland and had a thick, Eastern European accent. What was she to do?

On the spur of the moment, she whispered to her daughters, “Dites à l’officier que je suis muette et que vous devez parler pour moi.” (“Tell the officer I am mute and that you have to speak for me.”). Either my mother or aunt did, and they were safe—that time.

Later, when the three had left Lille and were hiding from the Nazis in a central France village called Avesnes, I don’t know how it did, but it came to pass that, according to my grandmother, only the priest and a nun in the village’s one Catholic church knew that they were Jewish. For fear of being exposed, and in order to keep up appearances, my grandmother would go to Communion on a regular basis and partake of the Holy Wafer.

After my grandfather had been abducted by Nazis and shipped off to Auschwitz in a cattle car (a fact my parents sadly confirmed, along with the date of his death from dysentery, at the Belgian Holocaust Museum in Bruxelles in the 1980s), a couple of fellow Belgians who knew of my grandfather’s being apprehended, approached my grandmother. They told her that for so many Francs, they could secure my grandfather’s release from Auschwitz. My grandmother gladly paid them and hoped with all her heart to see my grandfather again.

She never did. The two thieves had simply absconded with her money. This occurred at a point in the war before the Nazis were rounding up women for the camps. My grandmother mustered the courage to go to the Gestapo and report the two for what they had done. For once in the history of the Third Reich, the Nazis did a good thing. They caught the two bandits, stood them up against a wall, and sent them on their journey to Hell.

Toward the end of the war, still running away from Nazis, my grandmother, mother, and aunt made it to Marseille. Their plan, their hope, their dream was to board a ship for England. They waited in line for hours on the given day of departure. Then escapees were finally allowed to board the ship. The line moved forward with them creeping closer and closer to the dock. Then, all at once, the gate to the dock was closed by a gendarme. Right in front of them!

“Pas plus de place à bord!” they were told. (“No more room aboard!”).

They were extremely dejected and saddened as they walked away from the ship…until the next day, when they got word that the ship they were hoping would free them from tyranny and death was sunk off the coast of France by a German U-Boat, leaving all three to go on living the rest of their lives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment