Lang Vei Extraction of Survivors Under Heavy Fire:

Unsung Heroes of the 176th Minutemen Assault Helicopter Company

By Mike Keele

Originally published in the April 2018 Sentinel. Photos courtesy Ray Cyrus

Ray Cyrus was an ordinary guy with a job to do in Viet Nam, but he wanted more. He fancied himself to be door gunner material, and extended his tour by six months to live his dream. He was assigned to the Minutemen in Chu Lai, and in February of 1968, he was gunning on “slicks” because he could see that they got more hours in the air than did the gun ship guys. So, on/about 7 February, ’68, he was assigned to go out on an emergency extraction mission at a beleaguered SF camp called Lang Vei.

Ray in ARVN fatigues. The 176th flew covert missions into Cambodia and Laos to drop sentries. They took their dog tags off for these missions and wore the ARVN fatigues for concealment in case they were ever shot down.

Crew Chief Teddy Spurlock (left) and co-pilot Bob Hartley (right) performing a pre-flight check. Da Nang, South Vietnam, 1968.

The flight from Chu Lai to Khe Sanh was a long one, which should have warranted a medal just for the flight, but the day was only beginning. Ray said that they fueled up at Khe Sanh, which is a lobbed mortar round down the road from Lang Vei, and even at that, they were driven away from the POL (refueling point) by mortar and/or artillery fire in Khe Sanh — and they hadn’t even gotten over their target area yet. He went on to explain that the crew was an odd assortment: The aircraft commander that day, Bob Hartley, normally flew as the “Peter Pilot”, and the PP, Tom Lake, was normally the aircraft commander. The crew chief was Teddy Spurlock, who kept some bubble gum and band aids on hand for emergencies. None of these men was likely to have realized the enormity of their mission until the pilots were briefed at Khe Sanh. Still, they took off for Lang Vei with high hopes of…….surviving.

Ray said they got in touch with a Covey aircraft, a Super Sky Master flown by a guy named Rushworth. With everything that was going on, the rotor-heads were relying on Rushworth pretty heavily, as he had time in grade in that AO. He told them that their job was to just glide on down where smoke was to be popped, pick up the surv-uh, troops and then get out. On the way in, there were indigenous troops firing AK47s and NVA troops firing AK47s, and it was a little hard to tell which was which, except that some of them were shooting at the Huey, and the rest were shooting at those guys. That gave Ray all the guidance he needed and he went to work in this target rich environment, where bullets and rockets and mortars were flying every which way.

Door gunner, Ray, with his fixed-mount gun. According to Ray, “Early on, our machine guns were mounted with bungee cords, but too often we ended up shooting our skids. Later we changed to fixed-mount guns, which limited our range some but spared our skids.”

By Ray’s recollection, there were no A-1 Sky Raiders in the air when he was there, so he was a little sore about not having any of the 176th Muskets along to provide gun cover. Still, a chance to snatch a few live bodies from impending death should never be overlooked, so they touched down right on the appropriate color of smoke. At that point, Ray encountered 1st Lt. Paul Longgrear, who had multiple wounds, but he was pushing other wounded men onto the aircraft. Ray said that, complicating Longgrear’s job, were a bevy of “civilians” who were scrambling onto the chopper, a problem the Lieutenant solved by ordering them off the bird at gunpoint. Ray said that one particularly tenacious sort was clinging to a skid as they made their take-off, and Ray could see that the man wouldn’t be able to hang on long enough to land with the rest of the load. This problem was solved when Ray stepped on the man’s fingers, causing him to let go at a speed and altitude which would not be likely to kill him when he got back to mother Earth. (an aside on this was a phone call Ray received years later from the pilot, Rushworth, who said he thought Ray had shot the man off the skid, (which he hadn’t) and saw this young, would-be sky diver crash through the roof of a hootch to end his flight.

First Lieutenant (1LT) Paul R. Longgrear, the Mobile Strike Force (MSF) company commander at Lang Vei, is helped to the Marine Aid Station at Khe Sanh Combat Base, 7 February 1968. (U.S. Army)

The incoming gunfire was horrendous, and they wondered how many rounds had hit vital spots on the Huey. Well, apparently none had, and they limped over to Khe Sanh where their load of survivors was discharged. Ray described an oft seen photo of Paul Longgrear being half-carried, half-dragged away from the aircraft by a Marine. By this time, Ray and the rest of the crew was assessing the damage to their helicopter: T-tt-twelve, th-th-thirteen, and on and on. One particularly grievous wound suffered by the old bird was a .50 cal round which went through a push-pull tube connecting the swash plate to the rotor blades. Now, that might sound innocent enough to you neophytes, but us rotor-heads know that to lose that one part, even if you’re sitting on the ground with the blades turning, is game over for everybody within shrapnel range.

Ray said they made a get-away from Khe Sanh as quickly at pleasantries could be conveyed. They limped as far south as Phu Bai, where there was an air field. The next morning, they got a replacement push-pull tube which Spurlock hammered into place, and off they went to beautiful Chu Lai-By-The-Sea. The bedraggled quartet was more than happy to get home, as everyplace they had stopped had been inhospitable, unless you like being shot at with small arms, large arms, mortars, rockets and maybe, artillery.

An amazing part of this story is that, although Marine CH-46s were flying race track patterns around the perimeter of Lang Vei, none of them was willing to land and make the extraction. And the most amazing part is that this one, lone Army Huey from 200 miles south of Lang Vei, flew in and got the survivors out and went home without so much as an atta-boy. So, does anybody know someone with influence who could make it possible for these men to be belatedly awarded the medals for bravery they so righteously earned?

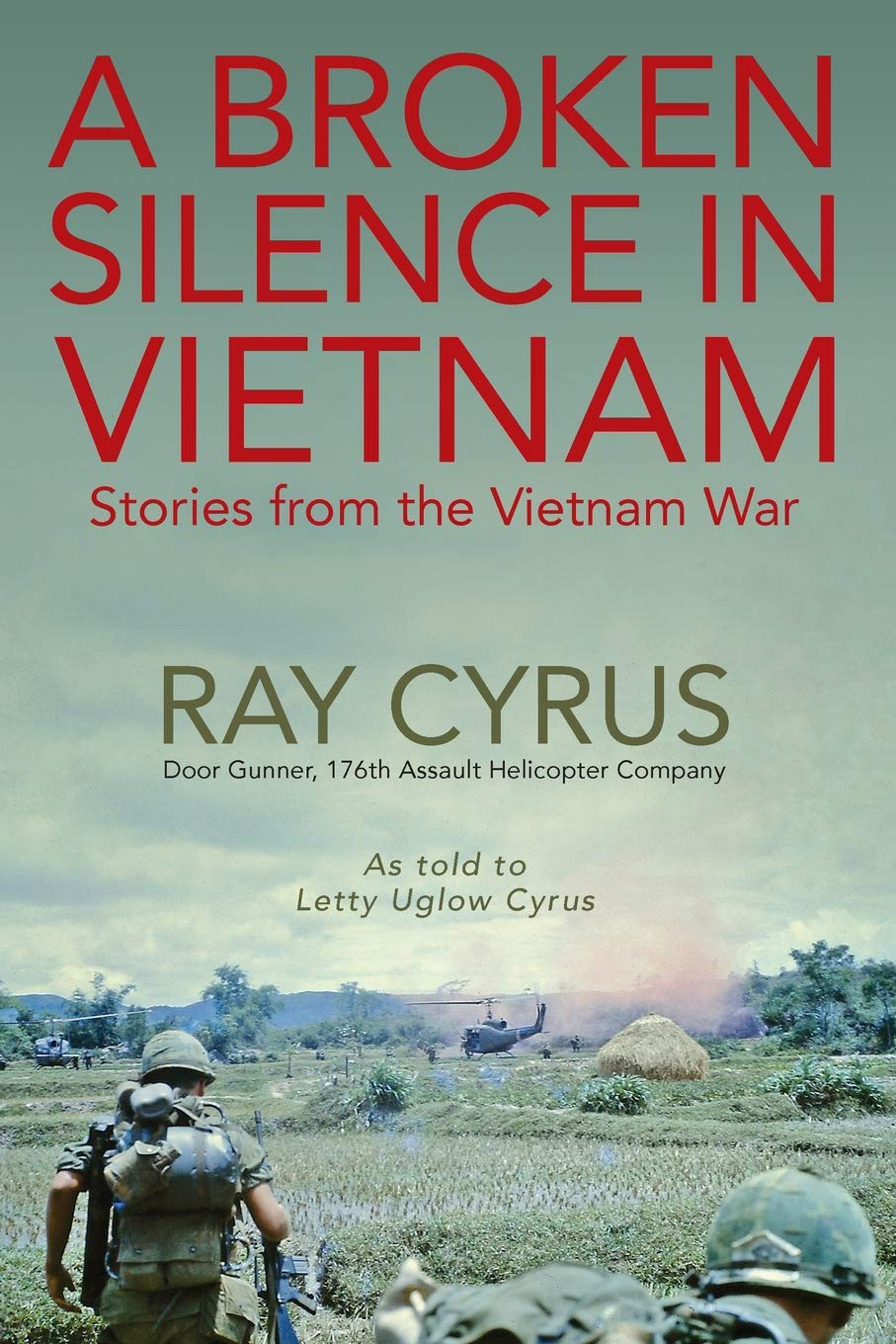

Ray Cyrus’ book A Broken Silence in Vietnam contains the story of his wartime experiences in Vietnam. Each chapter is followed by stories of several fellow Vietnam veterans Ray met out in public places while wearing his Vietnam veteran hat.

The book is available for purchase at major online bookstores and Outskirtpress.com, the publisher’s website.

About the Author:

Mike Keele, who passed on April 8, 2023, became an honorary member of Chapter 78 in 2010. He was also a member of the Special Operations Association, and a life member of the 1st Cavalry Division Association.

He was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, beginning as a door gunner in Vietnam. In late 1967 thru the summer of 1968 he served as Crew Chief with a very active air section of the 1st Cav missions flying across the fence and over the A Shau Valley into Laos supporting SOG recon teams and missions supporting conventional units in the A Shau Valley — the most dangerous area of operations in I Corps in northern South Vietnam.

Mike Keele and his wife Cora.

Leave A Comment