An Excerpt from

The Lair of Raven

By Colonel (Ret.) Craig W. Duehring

From The Lair of Raven, published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (December 24, 2014), pages 61-84, reprinted with permission.

Editor’s Note: Author Craig Duehring, having acquired many flying skills, used and improved them during his tour in Vietnam. He was in a small, slow propeller driven plane, braving danger so that he could keep those of us on the ground supplied with intel and fire support. That includes earning 2DFCs, one in my A camp’s AO (Duc Hue A325), which ran between his FAC base at Duc Hoa and the Cambodian border.

A short time before the Cambodian Incursion began (May 1st through June 30th 1970), Craig decided he wanted to “see more action” and extended for another tour to join a secret unit, working clandestinely in Laos.

This selection from his book picks up where he finds out, upon returning from a FAC operation, he is immediately going to the unit, much sooner than he expected. It ends talking about the wonderful Hmong people.

Chapter 3

Arrival in Laos

Laos

So, I said goodbye to my Army and Air Force buddies and headed off to my new life. On Friday, April 10, 1970, after one night in real civilization in Bangkok, I boarded the “Klong” C-130 flight to Udorn RTAB in northern Thailand. Once there, we circled the base for at least an hour awaiting clearance to land. Out the side window I could see fires burning at various spots on the base. Later, I learned that an RF-4 had been shot up over the Chinese Road and lost control on final. The pilot shoved the engines into afterburner and both aircrew members bailed out. The flaming aircraft struck the AFRTN station at change of shift and killed 19 people. It then traveled through two “Colonel’s trailers,” took out a newly remodeled but unoccupied wing of a barracks and ended up in the swimming pool. One of the aircrew members landed in the BX parking lot and his ejection seat smashed through the roof of the base theater and landed in the front row.

I dragged my way to the passenger terminal where I was met by an officer attached to Detachment 1 of the 56th Special Operations Wing – or “home” when we came to Udorn and our unclassified PCS destination. He asked if I had any civilian clothes in my bag to which I replied, “Yes.” He continued, “Then go into the men’s room and change and give me your wallet.” I handed over my wallet and dragged my duffle bag through the swinging door. When I came out, he said, “You will never wear a uniform again until you are back in the states on your final PCS move. And, these cards that refer to the military such as your club card, your check book with your rank on it, etc. all have to be removed.” As we drove to the Det. 1 headquarters, he continued, “I will lock your uniforms in a CONEX and these cards and checks will be kept in a safe in Intel where you can get at them, if needed.” He gave back my ID card, my Geneva Convention card and my flight cap. In the event that we were shot down and unable to escape, he explained, we were to attempt to claim our rights as prisoners of war with our cards and to quickly put our flight cap on in an attempt to be captured “in uniform” and not shot as a spy. By the way, it never worked. No Raven, who was not able to escape, was ever taken alive. This fact was brought out to me very graphically some months later when my very good friend, Park Bunker, who followed me into the Raven program, described his own death on the radio as it took place. Another Raven who was shot down after I left, who probably died in the crash, had his body stacked on top of the airplane where it was burned in full view of his friends.

I spent a great night as a guest of my newly found friends at Det. 1. Their jobs were to instruct Thai, Lao and Hmong student pilots how to fly the AT-28. This airplane was the Navy version of the T-28 Trojan with the large engine and 3-bladed propeller. It was outfitted with 6 wing bomb stations and 2 wing-mounted .50 caliber machine guns. When they weren’t instructing, they flew bombing missions into northern Laos. We got to know all of these Air Commandos and usually saved the best targets for them. Imagine the challenge in teaching a young man to fly in combat when he didn’t even know how to drive a car—and in a language that was foreign to his tonal language.

Two days later, I was driven out to Det. 1 where I met my first “real” Raven (possibly Will Platt), who dumped me into the back seat of his Bird Dog and off we went, across the Mekong, landing at Wattay Airport at Vientiane. There was a small air terminal on the west side of the field but much of the north and east sides were filled with Air America airplanes – neat airplanes like C-130’s, Pilatus Porters, C-47’s, C-123K’s, Volpar’s and bunches of helicopters – UH-1’s and H-64’s. It was magic. We taxied off the southeast end of the runway and onto the ramp where the Lao T-28’s were parked in neat rows and O-1’s were parked individually among sandbag and PSP revetments. We drove down to the American Embassy compound where I met the chief Raven, Lt Col Bob Foster – probably the finest Air Force officer I’ve ever met. What a change from where I had come. I left the worst Air Force officer I’ve known and sat down with the best. I was nearly in shock.

The Kingdom of Laos was divided into 5 military regions simply numbered MR I through MR V. In each was a major city that hosted the flying operations of the Royal Lao Air Force, Air America and the Ravens. The cities were Vientiane, the royal capital of Luang Prabang, Pakse, Savenneket and General Vang Pao’s guerilla headquarters at Long Tieng. Twenty-one Ravens were authorized in country but I never saw quite that many during my 11-month tour. But, there was a rapid turn-over. The concept was that a FAC or fighter pilot would serve in Vietnam for 6 months of a normal 12-month tour; then he spent 6 months as a Raven. The Raven tour was split into two 3-month tours; one at Long Tieng or Lima 20 Alternate, as it was also called – or just plain “Alternate” – and 3 months at one of the other sites. The reason for this was simple. About half of the Ravens were flying out of LS-20A at any given time because that was where most of the fighting was taking place. The threat was consistent up there while at other locations, the threat was more sporadic.

I had been told that, because the NVA had been rocketing LS-20A every night, the Ravens stationed there had moved back to Vientiane to sleep but flew north every morning, cycling out of LS-20A all day before returning to Vientiane. This was normal during the dry season when the NVA could move heavy equipment over the dirt roads and through shallow rivers. During my welcome interview I prayed that I would be sent to LS-20A and finally, Mr. Foster (the officers were all referred to as Mister) said, “Well, Craig, I am going to send you up to Long Tieng to work with Gen. Vang Pao.” I felt ready to jump up and cheer. “What I want from you is to do the best job you possibly can.” “And, if” he continued, “in the process, you piss somebody off; you send them to me because 50% of my job is to keep people off your back so you can fight.” Thus, began the steady growth of deep respect that I developed for this man in the months that I was privileged to work for him. From that point on, I would have done anything for him. And, I would have died before I let him down.

Almost as an afterthought I asked, “I was scheduled to come to Laos a couple of weeks ago and didn’t get the word to move so another guy was sent and I was told that there wouldn’t be an opening until August. Then I was told to hurry up and go. Can you tell me what happened?” Mr. Foster took a deep breath and sat back in his chair. “Hank Allen,” he began, “was scheduled to return home a week or so ago. The person who came to replace him was Dick Elzinga. Dick arrived 10 days ago. As is the custom, the departing FAC normally checks out the new guy so Hank and Dick took off from Vientiane the next morning (March 26, 1970) in a Bird Dog and, after (I think) a stop at Long Tieng, took off and were never heard from again.” It took only a second for what he said to sink in. If I had received the radio message and departed on time, that would have been me in the back seat of that missing airplane. So, I replaced the guy who replaced me. That story set the stage for many close calls that were to occur in the months ahead.

I met my new family that night including A.D. Holt, Stan Erstad, “Weird” Harold Mesaris, Jeff Thompson, Brian Wages, Jim Cross, Mark Diebolt, and Jim Struhsaker who was also known as T-shirt because of his habit of flying in a white T-shirt, blue jeans and cowboy boots. He also had the greatest handlebar mustache I’ve ever seen—with the possible exception of the one worn now by Sam Elliot. We probably ate a quick dinner before heading down town for a night of bar-hopping. Our little house was crowded and so the new guy got the couch in the front room.

On Wednesday, April 15, 1970, the guys raced through a pre-dawn breakfast and took one of the jeeps to the airport to take-off for a full day popping bad guys. Tom Palmer, a major in the Air Commandos, sat down with me for a minute and explained what my check out would consist of. At the airport, I grabbed my shoulder bag of new 1:50,000 scale maps with a 1:250,000 over-all navigation map, a set of 7 X 50 binoculars, my Smith & Wesson .38 combat masterpiece, a survival vest, a set of dark glasses, my helmet mounted with a boom mike and hiked out to the back seat of a waiting T-28. We took off and headed up towards the mountains and the famous Plaine des Jarres (PDJ). The others were already out there and putting in air strikes in the morning sun. Tom showed me the territory which consisted of mountain after mountain after mountain. Try as I might, I was so lost I couldn’t believe it. After all, I’d never flown in mountains before and certainly not when people were shooting at me. Tom put in an air strike or two and, after 2 hours, we landed at the secret base of Long Tieng (also known as LS-20A, Lima 20 Alternate, Alternate or Channel 98 for the TACAN station on the ridge nearby). The 4,200-foot runway lay hidden among the sharp, karst mountain peaks with houses and huts and ramps all around it. The only way to land was to the west while the only way to take-off was to the east. As soon as a pilot cleared the end of the runway on take-off, he side-stepped to the right to allow the other aircraft to land in the other direction. You landed every single time as the sharp peaks at the west end made a go-around very unlikely. I quickly noticed the rusting wing of a C-123 that tried a go-around quite unsuccessfully.

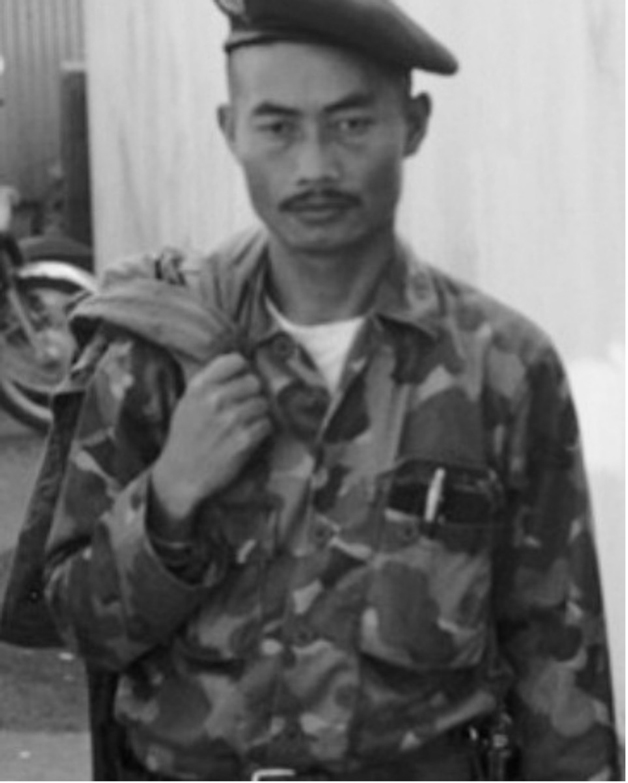

Capt Yang Bee (Photograph Raven William E. Platt Collection)

Long Tieng, Laos, Lima Site – 20A

We took a short break, met the Intel crowd and some of the maintainers – including both Air Force crew chiefs and Air America contract Filipino crew chiefs. Then we climbed into an O-1 with me in the front seat and Tom in the back. Now it was my turn to put in some air strikes which I did, apparently to Tom’s satisfaction. My log book says “Saw 5-man NVA patrol; 2 A-1’s Dragon White; 2 A-1’s Dragon Red; 2 F-4E Gallup; 1 Sec(ondary) Fire; Mr. Palmer in back.” We landed after lunch and hiked up to the Air America hostel for some fried rice before Tom turned me loose on my own. He introduced me to the chief “backseater,” Captain Yang Bee who the guys called General Ky since he looked a lot like the South Vietnamese Air Force Chief of Staff, General Nguyen Kao Ky. The backseaters (call sign “Robin”) were soldiers in VP’s army who had learned English to one degree or another and who often rode with the Ravens to translate the requests of the Hmong officers on the ground. Sometimes we flew with them and sometimes we did not. I tended to fly with them very often. Yang Bee was the best and his English was excellent. He was also a very dynamic individual who was very close to VP. Tom’s specific instructions were to go out and get familiar with the area but do not direct any air strikes – especially on the first day in country. Give them to the other Ravens. I clearly understood and told him so.

We took off and Yang Bee started talking excitedly on his radio in the back seat. After a bit, he called to me on the intercom. “27” he said. They couldn’t remember our names but knew our individual call signs; mine was Raven 27 which told the world that I was from Military Region II. “We must go LS-26 (Xieng Det) now. Many enemy, maaany enemy attack right now.” A troops-in-contact situation or TIC; the highest priority mission was underway. “Yang Bee, we can let one of the other Ravens handle it. We are not supposed to direct air strikes today.” “No”, he replied, “no other Ravens are airborne. We must go quickly. The fighters will be coming soon.” I checked with our radio operator and sure enough, all the other Ravens had landed to refuel. I was up there alone. There was nothing else to do but to call Cricket, the orbiting (ABCCC) Airborne Command and Control Center, and see what fighters could be sent to me.

We arrived overhead of the besieged outpost while Yang Bee kept up a steady stream of unintelligible chatter with his contact below. Soon, a flight of A-1’s, Zorro 44 & 45, showed up and I directed them on the battalion-sized enemy force which was holed up in a deserted village and at other locations surrounding the Lima Site. The A-1’s were a great asset because they could stay in the area for hours and carried every kind of ordnance imaginable. The fire was extremely accurate and the enemy moved around quite a bit. When the A-1’s were Winchester (out of ordnance) a second flight of A-1’s, Firefly 40 & 41, came on scene. By this time the enemy was on the move so we simply chased them. There was a lot of ground fire reported but that comes with the territory. They were followed by a flight of 2 F-105’s, Dallas 1 & 2. Finally, a third flight of 2 A-1’s, Firefly 46 & 47, arrived and we chased the enemy into the jungle and forced them to break off the attack. The Hmong soldiers were extremely happy and said that 100-200 enemy soldiers had been killed by our air strikes. I landed after a 3-hour mission, really feeling like one of the guys. It was late in the day, so after refueling, Yang Bee and I flew back to Vientiane. We became good friends as the months passed. Amazingly, he is one of the few backseaters who survived.

I didn’t think too much about the mission until I spoke with one of the flight leads again several weeks later. He was astounded to learn that my “reward” was the “thanks and love of the Meo (Hmong) people.” They were all awarded DFC’s. He sent a letter on my behalf to the embassy, and I was subsequently submitted for a DFC, as well—my 2nd.

Here is the letter that the flight lead sent to the embassy. I have a photo copy.

Undated letter—probably around May – June, 1970

Department of the Air Force, Headquarters 56th Special Operations Wing, APO San Francisco, 96310. Subject: Letter of Commendation

To: Mr. Robert Drawbaugh, Project 404, APO 96352

This letter is written in hopes of rectifying an apparent injustice to Raven 27. On 15 Apr 70 I participated in an operation with Raven 27 and two other flights of A-1’s which resulted in the saving of a Lima site, countless lives and the rout and destruction of the enemy forces. It was my understanding that this letter was to have been written by the Flight Lead of the first flight. I recently discovered that it was never submitted, consequently this correspondence, even though belatedly.

On that date, Raven 27 answered the distress call of friendly forces at a Lima site under attack by a battalion of hostile forces. Issuing a request for strike aircraft he proceeded directly to the scene and through directions from the friendlies and careful, low altitude searching he discovered the enemy forces hiding in a nearby, now deserted village. By the time the first flight of A-1s arrived he had located several concentrations of hostiles and proceeded to accurately brief and work the targets. After each attack, Raven 27 swung down low over the village to assess the effect of the ordnance and to detect any movement of the enemy troops. Once the hostiles were struck, they began to fire back and every pass by Raven 27 drew heavy SA/AW ground fire. His marking was so accurate that the enemy were driven from their hiding places, many of them killed enroute, and forced to seek refuge in available fortifications. Raven 27 however, had observed each movement and he directed my flight against the bunkers. With complete disregard of the heavy ground fire, he went back in after each pass to make corrections for the next ordnance. So devastating was the placement of ordnance that the enemy broke and ran. Raven 27 terroriously (sp?) stuck to their trail in spite of their concentrated attempts to shoot him down. Following them up into the hills, Raven 27 directed still a third flight of A-1s against the now decimated force. His final flight completely disorganized and scattered the remaining hostiles and the force was never encountered again by friendly forces. A later friendly sweep through the area revealed 150 KBA in the village and along the route of the retreat.

Raven 27’s courage in the face of extremely intense and accurate ground fire made it possible to save the friendly Lima Site. His accurate and professional FACing resulted in the confirmed death of 150 enemy troops. His outstanding abilities are deserving of high recognition.

Signed: Richard E Michaud, Lt Colonel, USAF, Asst Deputy Commander for Operations

So, on my first day in Laos, I 1) was checked out; 2) flew 4 sorties; 3) flew 9 hours and 10 minutes of combat time; 4) kept a friendly outpost from being overrun; and 5) earned a DFC! I knew it was going to be a hell of a tour.

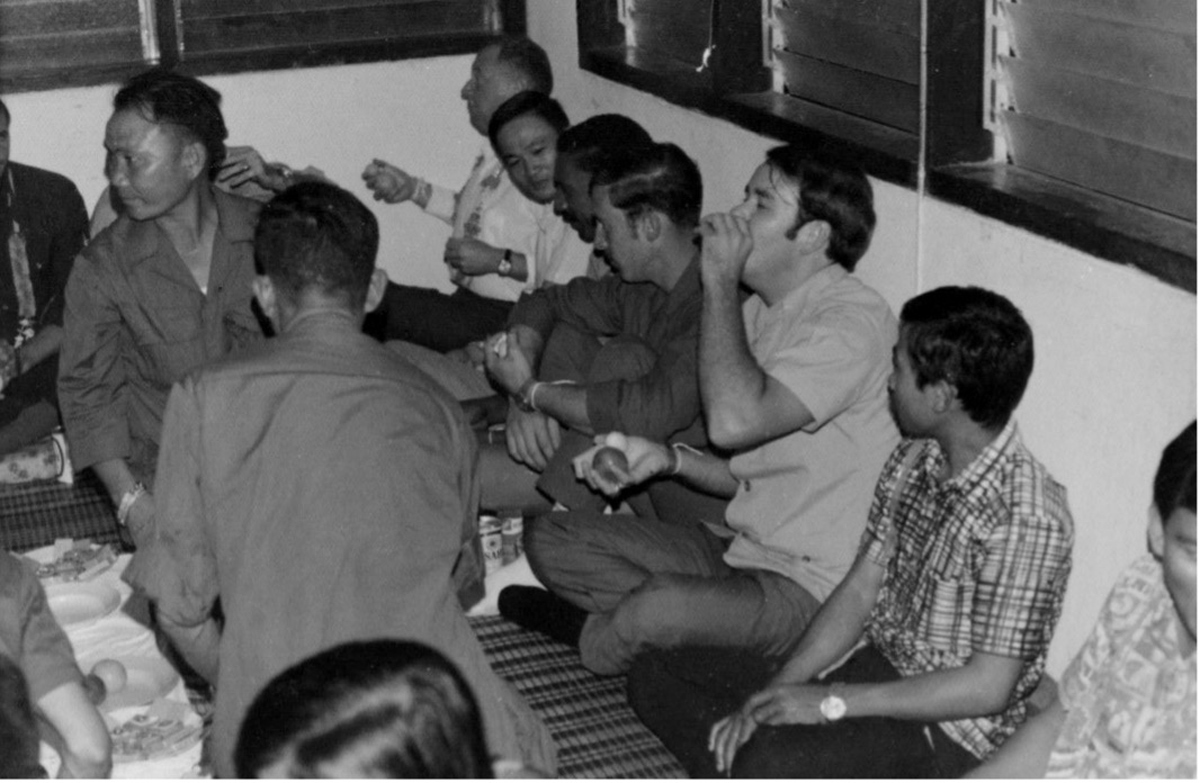

Craig Duehring, Bill Lutz, Jeff Thompson, Maj Gen Vang Pao, Nate Classen, Jim Hix, Grant Uhls, Chad Swedberg, Radio Operator, Long Tieng 1970

Vang Pao

On the evening of the second day, Jerry Rhein, the AOC Commander, took me to Vang Pao’s house for dinner. Jerry was a remarkable pilot, an air commando from the ground up who was assigned to run the air support mission for General Vang Pao. Jerry was a combat veteran in the A-1 Skyraider and later in the year, he led the A-1’s on the famous Son Tay raid into North Vietnam. General Vang Pao was a legend throughout Southeast Asia. He was a Hmong (or Meo as we called them at that time; Meo means savage) and the first Hmong to be commissioned in the French Army. According to Bernard Fall, in his book Hell in a Very Small Place, Lt Vang Pao was one of only a handful of Laotian officers who performed exceptionally well. In fact, he led a company of 300 soldiers during the battle of Dien Bien Phu in the spring of 1954. He rose to become the only Hmong general in the Laotian Army. He was also the leader of his people and led the fight against the communists for years. He had six wives, one from each of the major families of the Hmong. He held the power of life or death and his decisions, for his people, were final. There are many legends surrounding this man, most of which are impossible to prove. But it can be said that, at that time, he was at the zenith of his power and he was smart, dynamic, charismatic, considerate and still human.

I changed into clean clothes and we drove the very short distance to VP’s house in Jerry’s jeep. While the general hosted dinner at his house every night that he was at Long Tieng, you never really knew who might turn up. So, we walked up to the door where VP was talking and waited for him to notice us. “Jerry, my friend, welcome to my house,” the general began. “General Vang Pao, I would like to introduce our newest Raven, Raven 27.” As I had practiced, I joined my hands together at the fingertips and raised them above my eyes along with a slight bow, in the Buddhist tradition of showing respect to a high-ranking individual. Simultaneously, VP stuck out his hand to shake mine. Then we both changed what we were doing—he joining his hands together and I thrusting out my right hand. We tried once more to coordinate our greetings and, finally, with a laugh, he grabbed my flailing hand and shook it firmly. “Welcome. And come inside.”

As I recall, the food was fairly simple—chicken, boiled whole and chopped with a meat cleaver, rice, fruit and vegetables and, of course, the inevitable White Horse scotch. There was very little furniture in the house so we sat on the floor. Several months later, I participated in a baci or ritual ceremony that involved the honorees sitting against the wall while VP sat in front of the first man. The first honoree held out his right hand, palm up and gently touched his left temple with his left hand. Those around him, who wished to honor the honoree at the same time, touched his elbow while touching their own temple with the other hand. Person after person would do this until there was a chain of people, each touching one side of his own head while touching the elbow of the person next to him. This allowed the bad spirits a route of escape. VP would take a length of clean, white string from an ornately carved silver bowl, and then bring the string up under the right wrist of the honoree, tying it with a square knot and twisting the ends in his finger tips and gently tucking the ends under the string. The idea comes from the spirit-worshippers of the region who believe that the body has many souls. By themselves, the souls are weak and vulnerable to bad spirits. However, tying them together with string makes the person stronger. As the string is tied, the one tying the string wishes the honoree health, long life, happiness, wealth etc. Then, a few small food items such as a package of crackers, a hardboiled egg, a banana etc. are placed into the hand and topped with a shot glass of lao-Lao, the traditional distilled liqueur or, in the case of VP’s house, White Horse Scotch. The honoree bowed slightly and attempted to raise his hand in a Buddhist greeting, then chugged down the shot of scotch. Once VP shuffled to the next man, his chief of staff would come and repeat the procedure followed by other well-wishers, all of whom knew where the plate of drink-laden shot glasses was set. During a lull, one of my fellow Ravens suggested that I eat something since the scotch had a delayed reaction.

Baci at Gen. Vang Pao's House

The next morning after the baci, I awoke with the worst hang-over I’ve ever had and about 15 – 16 strings on my wrists. I cannot drink dark liquor to this day. For special occasions there was often music provided by traditional instruments. On the occasion of the Hmong New Year during the winter (dry season) of 1970-71, we left the baci and danced on the roof. I doubt the Hmong ladies took much pleasure in dancing with us. And, the dancing was totally unlike western dancing. The ladies lined up in a line on one side while the men lined up across from them. The dancing was the twisting and turning that you normally associate with Thai dancers. On yet another celebration, we watched as thousands of Hmong walked up a mountain holding lit candles. I don’t recall the reason for the celebration but the effect of thousands of flickering lights on the mountainside was impressive.

This would be a good place to repeat a story that I heard from several reputable sources in the CIA about how they had introduced White Horse scotch to VP. It seems that, early on, VP asked the agency folks what Americans would like to drink. One of them replied that scotch was very much appreciated to which he replied, “Good, order a case of the best scotch for me.” Knowing that they had probably opened Pandora’s Box and that the agency would be providing scotch for a very long time, they picked up a case of White Horse and he quickly settled for that. The rest is history.

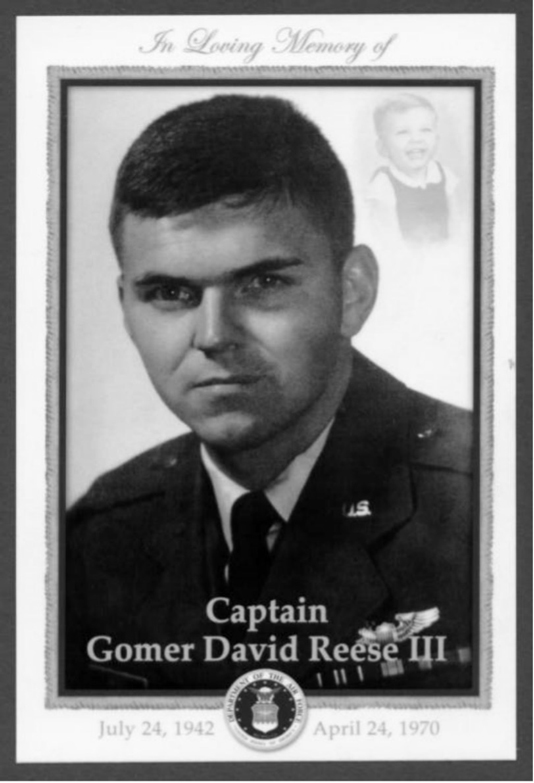

On April 23, barely a week after my baptism by fire, another new Raven arrived by the name of Dave Reese. He was scheduled to replace Jim Cross who was within a few days of going home. Jim was a very sharp officer who had worked as a Senate page. He planned a career in politics and already had an impressive network set up. Dave Reese had come like all the others, from a tour in Vietnam. He was a very likeable guy who seemed to fit right in. I don’t recall what we did the day he arrived but it probably involved touring the local bars and clubs in Vientiane. On the morning of April 24, 1970, we all met at the table at our house in Vientiane and each person said what he intended to do that day. I remember sitting across from Dave Reese, now the new guy, but I don’t remember the conversation. We headed out to the airport and I flew to some area that I’ve long since forgotten. At lunch time, Jim and Dave landed in the U-17 after looking around the area, grabbed a bite to eat and took off again, all while I was airborne. I was about to land when I heard a call from Mark Diebolt, who was flying the AT-28 and who was talking to Jim Cross, but I could only hear one side of the conversation. Jim and Dave had unwittingly flown over Roadrunner Lake which, recently, had been surrounded with heavy duty 37 mm anti-aircraft guns as well as ZPU 14.5 mm machine guns, and on towards Ban Ban. Somewhere around there, the U-17 took 3 hits of anti-aircraft fire. Jim pointed the aircraft south and sought to put some healthy distance between themselves and the big guns. Mark Diebolt intercepted him at the southern edge of the PDJ and saw the aircraft below him in a steady descent. Jim said he had jettisoned his rocket pods and was hoping to clear the ridgeline in front of him. Mark looked down and actually saw the trees of the jungle through the hole in the wing. A cloud moved between them and, when Mark cleared the cloud, he saw smoke and fire rising from just short of the ridge line. Only the AT-28 carried a parachute so bailing out was not an option. We were unable to recover the bodies.

In 1994, my wife and I quietly flew into Laos for a 10-day visit. During that time, we stopped at the American Embassy and were briefed on the progress of finding MIA’s. When they showed us the location of the dig for Jim Cross and Dave Reese, I knew immediately that they were looking in the wrong place. They were on the south side of the low ridge (i.e. the back side) while Jim and Dave had crashed on the north side because they could not cross the ridge line to the valley in the south. They promised to try again.

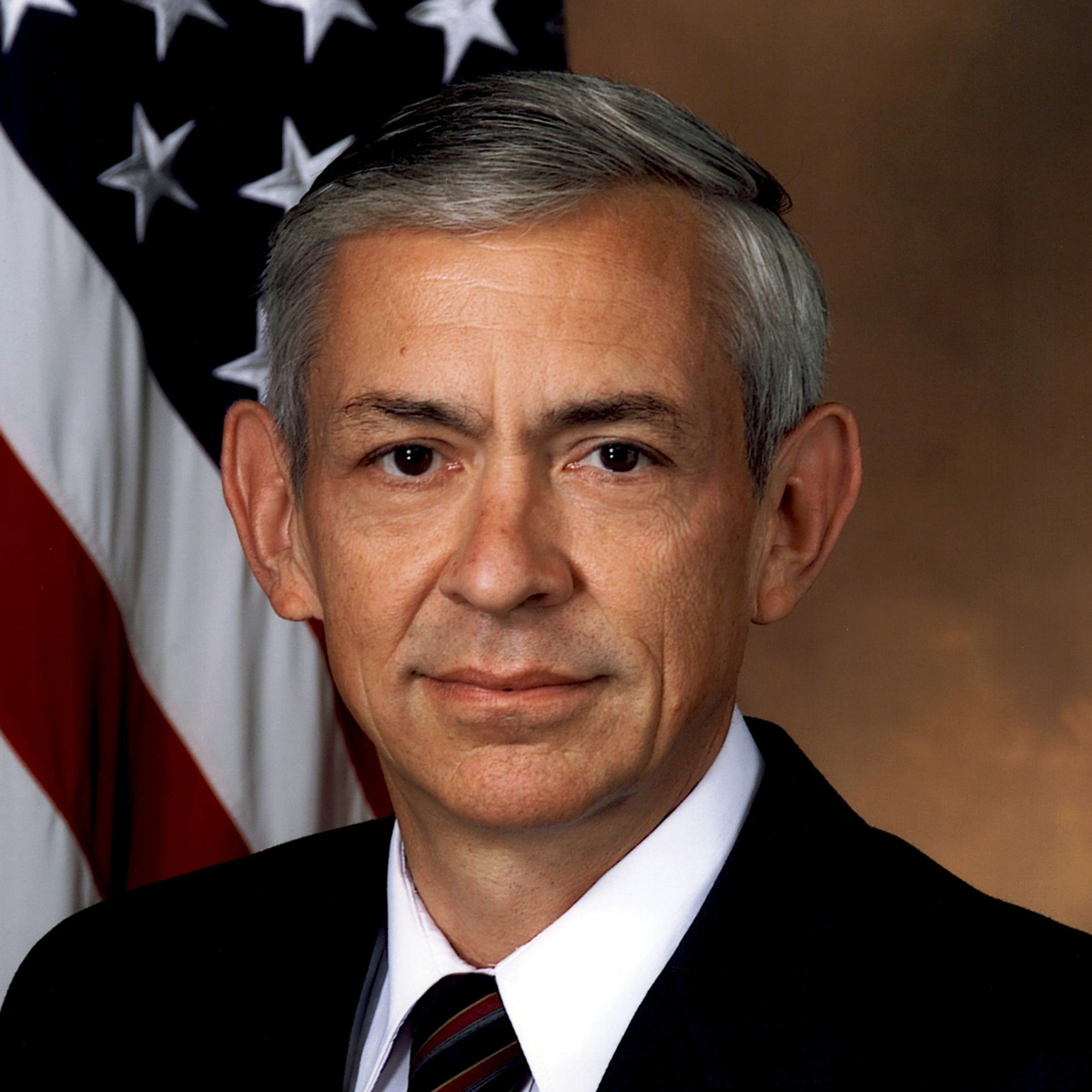

While I was still the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force, a member of my staff brought a message to me from the POW/MIA folks in San Antonio. They wanted me to know that they had recovered some bone fragments which had been positively identified as coming from Jim Cross and Dave Reese. I was in a state of shock and, at the same time, extreme joy. Actually, there were 3 groups of remains – one from Jim, one from Dave and one that definitely came from the wreckage but could not be positively identified as either man. In October, I flew to Ohio where I had the honor of presenting the flag to Jim’s father along with fellow Raven Ron (PF) Rinehart. Then, in the spring of 2010, I participated in the burial of Dave Reese as well as the burial of the common remains here at Arlington National Cemetery. Members of both families attended, united now as they were on the day that the news was given to them 39 years earlier. Several Ravens attended as well. It was an emotional time for all of us. As is the custom for all Ravens, we threw a nickel on the grass (to save a fighter pilot’s ass). Later, I returned to the grave one last time and left a shot glass of scotch on the marker.

Jim Cross Headstone and Scotch

Life at Long Tieng (LS-20A)

The life of a Raven was incredibly unstructured. At LS-20A, we had a Raven house or “hooch” as we called it, which was built of all dark wood. There was a large room where we could watch 16mm movies that came in by C-130 along with the food and normal supplies. The room had a bar that got plenty of use although we actually preferred the CIA bar over the bear cage. There were 3 black bears in that cage, which butted up to a rocky hillside and contained a cave. The male bear was simply known as Floyd or Papa Bear. Then there was Mama Bear (or Eartha) and Baby Bear – sort of what Goldilocks found in the bears’ house. They were fed but Papa Bear liked his booze. The safest way to supply his “needs” was to remove a floor board in the bar over the bear cage. Floyd would stick his snout through and make begging noises until someone poured a beer or something else into his waiting mouth. One night we were mean to old Papa Bear and poured down just about everything we had in the bar – to include some awful peppermint schnapps. Given enough alcohol, even a black bear can get drunk. Well, he finally sat down on his butt and moaned. Then, he got up and headed towards the cave where Momma Bear had parked herself at the entrance, with Baby Bear behind her. When Floyd approached, Momma Bear swatted him on his nose which knocked him back on his behind. I guess the poor guy spent the night on the concrete floor because, the next morning, he was sitting there with red eyes and moaning with a probable hang-over. Oh, the poor guy.

Floyd (aka Papa Bear)

We had a kitchen but usually ate our meals with the CIA guys in the dining hall they had, that was run by some excellent Thai cooks. There were bathrooms with pictures of stick figures showing how to use a toilet seat. This was necessary because the Hmong who worked for us used our facilities, too. Since they were used to squatting on the ground, they often hopped up on the toilet seats before using them. Their weight was too great and the seats inevitably broke. We had a radio room in that building which was run by Combat Controllers from Hurlburt Field in Florida. One day, one of our radio operators, who will remain nameless, found an old pistol in the desk drawer. It fascinated him and he cleared it of ammunition, so he thought, so he could have a better look. I walked into the radio room just as the gun fired and a hole appeared in the floor between my feet. We stared at each other in shocked silence for a moment while I did a quick check of my body for unplanned leaks and he started babbling “I thought it was empty. I looked at it first. I’ve always been around guns all my life. I’m very, very sorry.” Then he broke down into tears. I didn’t even have time to get angry. All’s well that ends well. It was an accident and only one of many close calls.

Our bedrooms were located in a 2 story “U” shaped house built out of cinderblock. My room was upstairs on the left as you entered the interior of the “U.” When I looked out my window, I could see the runway as well as the massive mountain in the distance that looked, to my imagination, like the stone tablets of Moses were displayed on the top. I had a cot and a wardrobe for my clothes. There may well have been a dresser there, too. I had bought a crossbow from a Hmong huckster and had hung it on the wall. My rifle was stored elsewhere but I hooked my pistol belt and the huge Randall hand-made survival knife with sharp teeth on one side and my name etched on the blade, over the “bed post,” such as it was. There was a desk pushed under the lone window that allowed me to watch the flight line as I wrote letters or read books and magazines. Above the window was an opening that was supposed to be covered by heavy, clear plastic. In the summer months, the fresh air was appreciated but, in the winter, it got very cold – not quite cold enough to freeze, but very cold. I bought an electric heater for my room but, every time the heater turned itself on, it would pop the circuit breaker and all the lights would go out in the rooms throughout the building. It got to the point where you hear an audible “snap”, the lights would go out and people started cussing out my poor little space heater (or me). So, I just turned it off and bundled up.

One day in October, I heard that a team of assassins may have entered the valley. We decided to wear our pistols for the rest of the day including the inevitable visit to the bar over the bear’s cage. Two gentlemen returned to their rooms to find the screen slit open but thee was no evidence of intrusion. Since we had often heard that there was a bounty on our heads, we took the warning seriously. However, my only threat came the following night when I entered my room and saw the biggest, ugliest grey and black speckled spider I’ve ever seen in my life, clinging to the painted cinder block wall near my bed. I slowly took off my boot and tried to smash it with the heel but the position was awkward and the spider dropped to the floor just as I cracked the wall with the heel of my jungle boot. It raced across the floor and even across a card board box. When it ran on the box, the feet made rapid tapping noises – it was that big. Instantly, I concluded that only one of us was spending the night in that room so I aggressively caught up to it and smashed it with my boot against the floor. Damn, it was big.

CIA Bar above the Bear Cage—Tom King, ?, Jim Hix, Jim Rostermundt, Bill Lutz, “Snake”

Intel had a room that we stopped at for the latest information. As the months rolled by, I became more cynical of the ability of the Intel community to provide much of anything that was timely and useful. Mostly, they were in the receive mode and sent what we learned back to 7/13th Air Force at Udorn. But, they did provide the day’s list of fighters (FRAG) along with their TOT’s. If we hadn’t discussed our plans the night before, we pulled them together at that time and each man just announced what he was going to do and what fighters he thought he could use. Once we were in the air, we kept in close touch with each other on the FM radio and modified our plans as necessary.

We were surrounded by endless mountains and jungle growth. There were flowers of all kinds and, especially, orchids which seemed to thrive in the high mountain environment. Jim Rostermundt (aka “Rooster”) bought orchids from locals and had his room filled with them. He said there were an estimated 5,000 varieties of orchids in Laos, of which only 3,000 had been identified and named. I think he owned one of each!

We also bought Hmong rifles, those wonderful hand-made flint lock rifles with hexagonal barrels and a wooden pistol grip. When we bought one, it came with a powder horn (actually made from an animal horn), a piece of bear skin that covered the firing mechanism, a small horn for flash pan powder and a small gourd to hold the shot in. No two rifles were ever alike. They were completely handmade. I bought three.

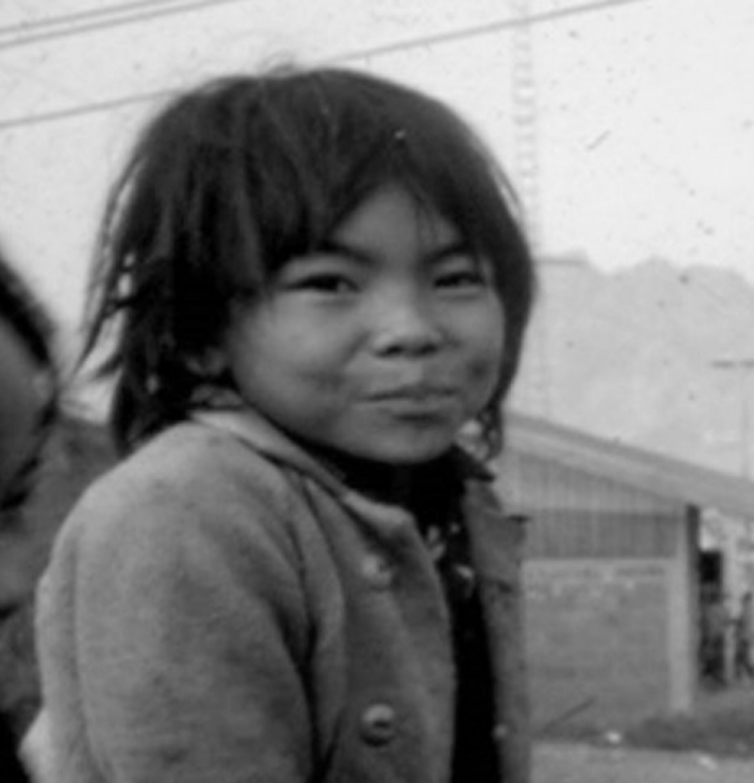

Hmong boys on the PDJ, 1994

The Hmong were mostly animist which meant they believed spirits inhabited everything – the rocks, the rivers, the mountains – everything. These spirits could be a great threat especially since they also believed that people were born with not one, but many souls. You were strongest when your souls kept close together. That is why, at a baci, strings were tied around your wrists – to tie the souls together and to give you strength. Little children were often seen with a cord around their necks and an amulet hanging from the cord containing good luck charms. The charms would ward off evil spirits while the cord would bind the young child’s spirits together. I snapped a great picture of a Hmong boy and his brother, wearing this cord and amulet, when Terri and I visited the PDJ in 1994.

There was a little girl, a beautiful little girl, who lived and played near our house. I saw her nearly every day. While her friends walked around as usual, she used a small crutch that was fashioned by one of the CIA folks. As a small child, she had become ill and her parents summoned the shaman, who dealt in colored injections. What these injections consisted of, no one knew, but they were every color under the rainbow. So, he took his dirty needle and shoved it into her leg, severing the femoral nerve. Thus, her lifeless leg dragged behind her and she pulled herself along. She was always smiling and giggling, and playing peek-a-boo or something similar. I believe I read that one of the CIA guys got her out of the country and brought her to America. I hope that is true.

Little Hmong girl with crutches (Photograph William E. Platt Collection)

The Hmong men wore a mixture of clothing styles. The soldiers wore uniforms, of course. But, the civilians wore the traditional black outfits (pants and shirts – which hung loosely over the pants) and the tight black cap with a brightly colored tuft on the top. It was reminiscent of Chinese clothing. Many of the young men had transitioned to western clothing. The young guys who worked in our house wore old clothes when they worked but, when they were going out for the evening, they showered and changed into very nice trousers and carefully ironed shirts and looked like they were going to a disco somewhere. They even wore western leather shoes but had to walk along the muddy streets with great care.

It always astonished me to see Hmong men wearing black suits on special occasions like Hmong New Year’s, weddings or funerals. Where they kept them, I do not know. I recall watching a bull fight on a holiday and seeing many of the men wearing black suit pants, white shirts and black vests without coats. They also often wore the black cap with tuft on these days, too.

About the Author:

The Honorable Craig W. Duehring is a native of Mankato, Minnesota. He joined the Air Force in December of 1967 and immediately entered Air Force Officer Training School followed by Undergraduate Pilot Training at Craig AFB, Alabama. He saw service during the Vietnam War in 1969-70, as an Allen Forward Air Controller with the 25th ARVN Division. In 1970-71, he was a Raven Forward Air Controller based in Laos. Subsequent assignments included a T-37 Instructor Pilot and Flight Commander at Craig AFB and Base Fuels Management Officer at Langley Air Force Base. He was an A-10 Flight Commander and Chief of Wing Training at RAF Bentwaters from 1978 to 1981. He served at HQ USAFE in the Tactical Fighter Operations Division from 1981 – 84. He returned to RAF Bentwaters in the A-10 during the period 1984 – 86. He returned to West Germany in 1986, and was stationed at Norvenich Air Base as American Community Commander and Commander of the 7502nd Munitions Support Squadron. He was subsequently Deputy Commander of Operations of the 406th Tactical Fighter Training Wing at Zaragoza Air Base 1989-91. He then spent 1992-93 studying at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, D.C. followed by a tour as the United States Air Attaché to Indonesia from 1993 to 1995. Duehring retired from the Air Force in 1996, having attained the rank of Colonel.

Col. Duehring’s awards include the Silver Star, Defense Superior Service Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross with one oak leaf cluster, and the Air Medal with 26 oak leaf clusters. He flew a total of 834 combat missions and 1525.8 combat hours. In 1988 he was awarded the Lance P. Sijan Award as the top leader in the United States Air Force in the senior officer category.

In 1998, he was an unsuccessful candidate for the United States House of Representatives on the Republican ticket for Minnesota’s 2nd congressional district. Duehring became the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs and performed the duties of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs in the period immediately before and following the September 11 attacks. In July 2006, Duehring became Acting Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Manpower & Reserve Affairs). In November 2007, President George W. Bush nominated Duehring to be Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Manpower & Reserve Affairs), and Duehring subsequently held this office until retiring from public service on April 30, 2009. In September, 2009, His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI conferred a Papal Knighthood on Duehring in the Order of Saint Gregory the Great at the level of Knight Commander with Star. On September 1, 2010, Duehring was appointed by Governor Bob McDonnell as a member of the Board of Directors for the Virginia National Defense Industrial Authority. On April 12, 2014, he was inducted into the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame.

Leave A Comment