AN EXCERPT FROM

FIRST TO

THE FRONT

THE UNTOLD STORY OF

DICKEY CHAPELLE

TRAILBLAZING FEMALE

WAR CORRESPONDENT

By Lorissa Rinehart

Excerpted from FIRST TO THE FRONT, Copyright (c) 2023 by Lorissa Rinehart, Permission granted by Lowenstein Associates, Inc., pages 295–307)

28

The Sea Swallows

She first heard of Father Augustin Nguyen Lac Hoa over the dying embers of a campfire on the Ho Chi Minh Trail from a couple of MAAG advisors debating who was the toughest man they had ever met.

“Nobody is tougher than Father Hoa,” said one of them, a veteran paratrooper. The rest nodded in silent agreement.

As a country priest in Canton Province (now Guangdong), China, Father Hoa had been pressed into teaching the sons of river pirates how to read. As compensation, his pupils taught him jujitsu while their fathers taught him the principles of guerrilla warfare. During World War II, the priest’s unlikely military training continued when the government drafted him into the army where he learned the basics of munitions. He survived to return to his flock. But after Mao Zedong seized power, Catholics became the target of mass arrests, torture, and execution. Father Hoa and his parish fled to Cambodia until communist guerrillas began to harass them there as well.

Resettling once more, this time on the mouth of the Mekong River Delta, they established the village of Binh Hung and gained citizenship in time for the 1959 national elections. Aware of their politics, the Viet Cong, who had recently gained a foothold in the region, told the priest that his village shouldn’t vote. Several communists were on the ballot and the Viet Cong knew his parish would cast their ballots against them. Undaunted, Father Hoa, along with every adult of voting age, trekked several hours to their polling place in the regional center of Tan Hung Tay. As a reprisal, the Viet Cong hung an eleven-year-old boy named Ah Fong from a cross with a sign on his chest reading, THIS CAN HAPPEN TO ALL YOUR CHILDREN.

Already twice made refugees by communists, the parish collectively chose to stand their ground this time. Putting his military training into practice, Father Hoa formed the Sea Swallows, a counterinsurgency militia named for the nearly indestructible species of tern that migrated through the Mekong Delta each spring. Since its founding, the Sea Swallows had grown from several dozen soldiers to a force of seven hundred that included volunteers from almost every province in South Vietnam.

Eager to meet this fighting priest, as she would later dub him, Dickey arranged for them to have tea at the American embassy in August. Over their second cup of oolong, Father Hoa invited Dickey to come live with them for a while, another first for any reporter.

The chopper dropped her off in mid-October. A squadron welcomed her on the landing pad, firing a twenty-one-gun salute and raising their flag. Dickey quickly fell into the village’s rhythm.

Every morning, bugles called the village to wake, soldiers to drill, and prisoners to work. Ducks and pigs and dogs and babies composed the chorus of afternoons. Stringed pipas, instruments similar to guitars, and mouth harps announced the end of the workday. Sometimes when the air was cool enough, the militia’s radio picked up the Saigon jazz station that was piped through an enormous Pioneer loudspeaker, washing the village in Coleman and Coltrane, Evans and Getz, Mingus and Roach. The resounding percussive of tanggu drums called the devout to evening prayers at the Our Lady of Victory Chapel. In the dark, gongs made from flattened mortar shell tips rang out the all clear every hour on the forty-five, except when incoming Viet Cong bullets made them chime like kindergarten triangles. This music played almost every night. The Sea Swallows replied with their own refrain of artillery, mostly left over from the French Indochina War, along with psyops messages broadcast over the same loudspeaker that earlier might have played jazz.

But more than defend, the Sea Swallows went on the offensive against the Viet Cong and had so far secured a five-mile perimeter around the village. Dickey of course insisted that she accompany them. The night before her first patrol, she joined the officers for dinner in their mess beside the Sea Swallows’ armory. On one side of the long table, two German shepherds, gifts from US Army Research and Development, strained at their leashes. On the other, soldiers tossed their scraps to caged boa constrictors. Dickey sat in the center beside the ranking officer, Captain Nguyen, who talked of the liberation of Vietnam while Dickey used chopsticks to feed succulent crab to the cat that had crawled on her lap. Occasionally, a soldier would interrupt, asking the captain to inspect his modifications on a 1953 French mortar or World War I bullets that had been polished back into working order. Each time, he nodded a hesitant approval. They needed new weapons, but these would have to do. After dinner, Nguyen handed her a carbine to carry the next day. “You might need it,” he cautioned.

Dickey went back to her quarters to practice carrying the gun along with her cameras. “How do Marine combat correspondents do it with an M-1?” she wondered in her journal, then packed her pockets with extra film and cigarettes for tomorrow’s march.

They left in a thick rain at dawn, made too much noise, and only had a captured flag to show for their mosquito bites. “I scratched like a civilian,” Dickey wrote. Still, the squadron gave her the flag. She would later unfurl this keepsake from her purse on stages in the Plains states in order to drive home the necessity of supporting the Sea Swallows and groups like them.

That afternoon she photographed the demolition class in the chapel. Like her, the instructor was an outsider, a member of the Vietnamese special forces sent here both to teach and to learn. She had met him before, what seemed like a lifetime ago, on one of her first patrols in the highlands.

“Don’t you get homesick?” he asked her as his students practiced inserting fuses. Then shyly added, “I think you are willing to die for your duty.”

“I’m sure you are too,” she replied, then added, “We might both live through our whole careers.” The look on his face told her she had said the wrong thing. He expected to die defending the freedom of his country. To think otherwise was tantamount to a dereliction of duty.

Dickey Chapelle—“She’s Ready to Defend America,” a portrait of Georgette Louise Meyer (aka Dickey Chapelle), as a member of the Women Flyers of America, an organization formed in 1940 to teach women to fly and then to ferry American bombers to Great Britain. (© Milwaukee Journal Sentinel – USA TODAY NETWORK; Reprinted with the permission of the estate of Dickey Chapelle)

A week later, Nguyen announced the next patrol mission beyond the walls of Binh Hung. The troops assembled in a portentous gray dawn. Dickey ignored the omen, instead scanning the faces of the hundred assembled regulars as Nguyen gave them their orders. “I was surprised to realize how many of the Binh Hung faces had become familiar and even a little dear to me in the ten days I have been among them,” Dickey wrote in an unpublished article about the operation. But combat, she knew, always made fast friends.

Nguyen dismissed them to load into the Sea Swallows’ fleet of weathered motorboats with mounted automatic rifles at the bow and stern. Amidships, soldiers clutched their American M-1s and French Lebels with shells in the chambers and their safeties off. Bathing children laughingly swam out of their way as they departed down the canal. Dickey noted with no small degree of sentimentality the woman who saluted the soldiers, then blew a kiss to her husband, blushing behind his Browning automatic.

Outside of the village, water lilies and floating buttercups swirled in the eddies of their wake. Skirting the edge, farmers on the way to market poled their sampans stacked high with bundles of watercress, bananas still on the stalk, baskets full of fish, and clinking bottles of home-brewed beer. On the banks, children played and fishermen fished, boatbuilders caulked their hulls, and housebuilders thatched a new roof. The whole scene seemed so utterly pastoral, so opposed to their actual purpose.

A stone lion and live Tommy gunners guarded a Buddhist temple just outside Tan Hung Tay where they rendezvoused with a company of Montagnard militia. “They are mountain people from central Vietnam,” wrote Dickey, “the Father and the captain have been delighted with their performance… My first chore of the day was to help prove it by photographing a Viet Cong corpse lying in the marketplace.” She then added parenthetically, “(I guess I should point out that in my experience the public exhibition of enemy dead is still considered a pretty normal part of warfare in every culture but our own.)” Inured by now to the spectacle of violence, the marketgoers hardly noticed the body as they went about their shopping. With equal nonchalance, Dickey focused her lens on metal spikes across his chest, classic Viet Cong booby traps, that he had been caught planting along the path into town.

Reports of an approaching enemy column took them farther down the canal to Van Binh, another Catholic Chinese refugee settlement where the Viet Cong had recently poisoned the drinking water and shelled its market. The village chief welcomed the Sea Swallows with a feast of pork liver soup, roast duckling, shrimp, crab, beer, and French brandy. Evening fell. Dickey slept in the same barracks as the soldiers and woke with them before dawn.

“The first firing came at 08:10 exactly,” wrote Dickey, “a few rifle shots and a submachine burst of three. Then for several minutes the fire was so heavy that I couldn’t count.” Dickey expended a roll of film and was loading another when she saw the mortar crew run by. She followed, film in hand, and dropped to one knee as the crew assembled the mortar in three and a half minutes flat. They fired. A dud. Military protocol dictated waiting ten minutes before loading a new shell in case the old one had simply yet to explode. But there was no time for such caution under heavy fire closing in on a thousand yards. Without hesitation, the crew reloaded and fired three more times. On the fourth, incoming fire slackened and the enemy dispersed.

Whatever misgivings the Sea Swallows or any citizens of Binh Hung had about Dickey disappeared after that. Farmers’ wives hosted dinners for her. The commander of Companies Six and Seven invited her to his wedding. She celebrated the Vietnamese Independence Day by setting off fireworks with the best of them, went to children’s birthday parties, and attended mass on Sunday. And, whenever the Sea Swallows went on maneuvers, she went with them.

She regularly joined them on perimeter night patrols and marched out to confront reported bands of Viet Cong. She came under fire nine times, endured clouds of mosquitoes so thick they clouded her glasses, and watched deadly snakes slither by her boots as she stood motionless for fear the smallest sound might alert the enemy to their location.

She described in gripping detail the dangers and difficulties of warfare in Vietnam that confronted the Sea Swallows even before one reached the enemy—charging water buffalo, mined canals and spiked foxholes, and terrain that both the Viet Cong and MAAG personnel considered equally impossible to traverse but which the Sea Swallows crossed by the mile. She portrayed them as they were under fire, cool and collected as any soldiers she’d ever seen.

“The Reds had chosen a spot where the walkers were cut off from the two boats by a hundred yards of swamp,” she wrote of her last mission with the Sea Swallows. “Suddenly there came a lone rifle shot followed by a second’s pause. Then half a dozen rifles spoke at once.” Among them she heard the sound of an American M-1, distinguishable by its cannon cracker sound. Dickey threw herself flat on the bilge as the rounds of fire intensified. “But it was not a mere single shot we were hearing now… Our own counterattack party had opened up on the Reds with burst after burst from their automatic rifles.” The firefight lasted an hour until there “came the detonation of what I took to be a grenade and finally— deep, shocking silence.” The enemy dispersed.

Refugees Crossing Hungarian Border—For weeks in the winter of 1956, Dickey documented the refugees risking their lives to escape the brutal Soviet installed dictatorship that toppled Hungary’s democratically elected government. (Wisconsin Historical Society, Dickey Chapelle, 1956, PH3301J, Box 2, Page 20, Image 4; Reprinted with the permission of the estate of Dickey Chapelle)

The Sea Swallows gathered their wounded and began their long trek back to Tan Hung Tay where they found a banquet laid in their honor. Word had reached Father Hoa that a battalion of three hundred heavily armed Viet Cong had surrounded the patrol, but he could not determine the outcome of the battle. “If there are survivors, we will sate them,” he told the women and children as they laid out the meal. “If there are not, we will rededicate ourselves to avenging their sacrifices.”

Father Hoa invited Dickey to sit at the head of the table with him. “I demurred,” she wrote, “I said that was a place for a soldier.”

“Sit down,” intoned the priest.

After dishes of crab, sweet-and-sour pork, roast goose, and broiled shrimp, it became clear why Father Hoa had wanted her to sit next to him. In front of everyone, he asked her to stand, then pinned the insignia of the Sea Swallows on the muddied shoulder of her fatigues. When she realized what he was doing, it took all of her strength not to cry. She felt honored and unconditionally welcomed. In other words, at home.

On November 6, 1961, nearly a month after arriving, Dickey left by helicopter along with the three who had been wounded in the previous day’s attacks. She lingered a long time at the porthole, watching Binh Hung fade like an island in the sea of Viet Cong territory.

Back in Saigon, a cable waited for her at the Majestic Hotel.

PLEASE FORWARD THESE WORDS TO THE FIGHTER OF BINH HUNG NAMED DICKEY CHAPELLE. WE EXTEND OUR BEST WISHES FOR YOUR SUCCESS. AS WE ARE MOVING INTO A LARGE OPERATION WE HAVE INFORMED ALL OUR FIGHTING MEN OF YOUR DEPARTURE. THIS AFTERNOON TWO COMPANIES OF OUR ASSAULT GROUPS MET AND HAD A BATTLE WITH THE ENEMY. WE HAVE HEARD VERY HEAVY SOUNDS OF GUNFIRE SO IT IS POSSIBLE THAT WE HAVE ENCOUNTERED THE ENEMY MAIN FORCE. IT IS SO HEAVY THAT WE ARE SENDING TWO MORE COMPANIES OF REINFORCEMENTS. WE HAVE NAMED THIS BATTLE THE CHAPELLE BATTLE. DUE TO LACK OF COMMUNICATION WE DO NOT YET KNOW THE RESULT.

In the end, the Sea Swallows won the day.

But for all the declarations of mutual respect and admiration, Dickey had arrived at, documented, and in some ways unwittingly abetted one of the darkest turns in the history of the Vietnam War. The first clue she failed to decipher were the Montagnards stationed at Tan Hung Tay. A moment’s pause might have led her to question why and how these indigenous highland men had come to be in the heart of the Mekong River Delta. The answer, of course, was the CIA. As with the Hmong in Laos, the CIA recruited and trained guerrillas from Vietnam’s polyglot of indigenous highland peoples only to abandon them to the communists when Saigon fell.

In coordination with the decidedly pro-Catholic and openly corrupt government of President Di?m, the CIA had also started organizing the many ethnic-Chinese Catholic parishes in the Mekong Delta into a clerical paramilitary program that formed an archipelago of anticommunist enclaves within the delta region. But this operation remained in its fledgling stage when Dickey was on patrol with the Sea Swallows.

However, even in their early stages, these operations were beginning to ramp up. On October 18, 1961, Dickey wrote a letter to Hobe Lewis at Reader’s Digest that read, “I am not being disappointed in my stay here. These Asians are daily and literally fighting Reds; I have been on four operations with them so far… They are heavily though not well armed and organized as semi-regulars… They are improvising the military doctrine of the future—and so if they succeed, the whole free world will be richer for it.”

Hobe then replied to her letter on October 23, writing, “With General Van Fleet and General Taylor both concerned with guerrilla warfare, I don’t need to tell you how urgently we would like to see an article on the subject. I cannot direct you since you know so much more about the subject than I do, but I do hope that you will give this top priority.” As to the generals he referenced, they could not have been more consequential to the Vietnam War. General James Van Fleet had been a gunner during World War I, a hero of D-Day during World War II, and a commanding general during the Korean War. President Kennedy had recently recalled him to serve as a consultant on guerrilla warfare. General Maxwell D. Taylor had been the commanding general of the 101st Airborne during World War II, had recently become chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and in 1963 would be appointed as ambassador to South Vietnam. Whether or not the military or the CIA gave direction to the Reader’s Digest editorial board, they were clearly the magazine’s primary audience.

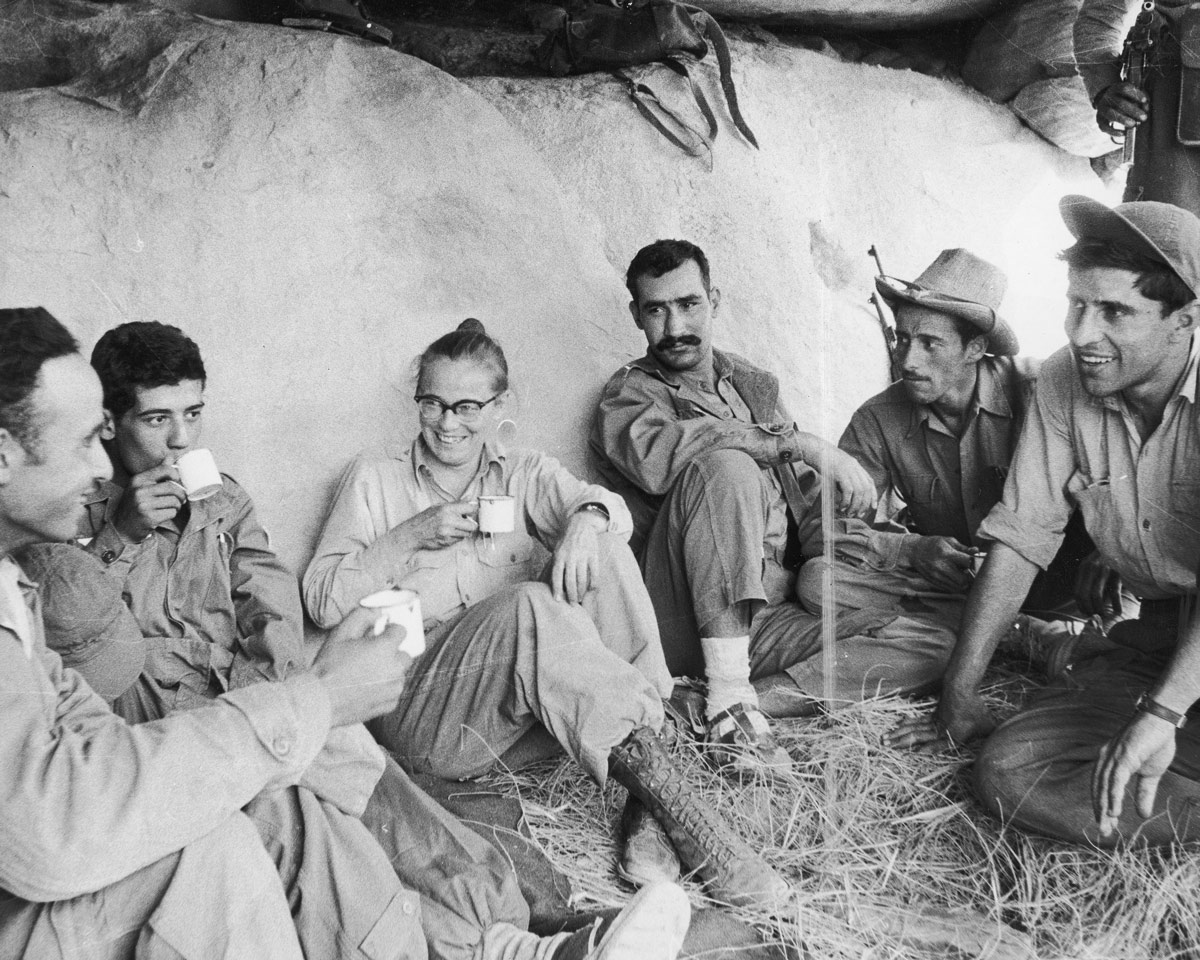

Chapelle and FLN Rebels—Dickey’s familiarity with military training made her comfortable with soldiers the world over, and likewise, they with her. Here, she shares a cup of Turkish coffee with members of the FLN Scorpion Battalion. (Wisconsin Historical Society, Dickey Chapelle, 1957, Image ID:12158; Reprinted with the permission of the estate of Dickey Chapelle)

Five days later, on October 28, 1961, Special Forces Major Donn Fendler was welcomed on the Binh Hung helicopter pad. His presence, though possibly unrelated to Dickey’s exchange with Hobe, was far from coincidental. In 1938, at the age of twelve, Fendler became famous for surviving nine days in the mountains of Maine after being separated from his family. When President Roosevelt invited him to the White House and asked him what he wanted to do when he grew up, he answered without hesitation that he wanted to join the Navy. Six years later, at eighteen, he did just that and fought in the World War II Pacific Theater with distinction. After the war, he reenlisted with the Army and trained in the 101st Airborne Division. When he arrived in Binh Hung, it was in the capacity of a military advisor, most recently and most often to the CIA’s Montagnards.

Dickey did not mention his presence in any of the articles she wrote and his name appeared only once in her journal. How long he stayed, she didn’t note, but an addendum to her photo captions for The New York Times indicated he remained long enough to go on one or more combat missions. “Publication of this photograph without prior security review by US authorities,” she wrote, “would be most embarrassing to the photographer. Unfortunately both the face and name of an American frequently on duty behind enemy lines are plain in the picture.”

The backward gaze of history all too easily connects these occurrences into the causality of what happened next. In early January 1962, only weeks after Dickey helicoptered out, CIA director William Colby ordered the fourteen-man “A” detachment of the Special Forces into Binh Hung on an extended assignment. As in Laos, they organized the citizens to clear a landing strip large enough to land a twin-engine Caribou transport plane. By midsummer 1962, some fourteen hundred light and heavy weapons had been delivered and the combined American-Chinese Special Forces team approached two thousand soldiers. In the CIA’s estimation, Binh Hung would serve as the nucleus of the Delta Pacification Program that in turn laid the groundwork for the expanded war that emerged in 1966 and 1967.

Though she witnessed most of these developments or was made aware of them by her contacts, Dickey failed to add these parts together into their grisly and inevitable sum. In this she was not alone. Indeed, most of her journalistic peers were content to keep quoting the Kennedy administration’s line that insisted the conflict in Vietnam amounted only to petty skirmishes that Saigon-based, US-backed forces had under control.

As one of the few willing and able to spend weeks at a time embedded with armed forces; one of the only accredited to paratroop; and the only reporter who wore the wings of the Vietnamese airborne and 101st Airborne and the insignia of the Sea Swallows, Dickey had a unique and hard-won knowledge of the early days of war in Vietnam. But as a survivor of the physiological torture of solitary confinement who came out of prison only to live her life primarily in active war zones, she only saw the walls closing in on her again as America’s losses mounted in Southeast Asia. As such, she searched for the only way to win she knew: fighting.

Back in the States, the Marine Corps chief of staff, Lieutenant General Wallace Greene, asked for an in-person briefing and update to her original “An American’s Primer of Guerrilla Warfare.” Dickey pulled no punches.

She began by characterizing the recent neutralization of Laos— meaning neither the USSR nor the US could claim it as an ally—as dangerously naive, while categorizing the half measures to contain communism with Vietnam as categorically ineffectual. “In fact,” she wrote, “in both countries the pursuit of both aims is now proceeding at a rate so slow as to suggest failure of attainment of any objective in the US interest.”

The solution by her estimation was an increase in commitment, if not with the number of men, then the degree to which they stood with and beside their Asian allies. MAAG personnel should be deployed to the villages where counterinsurgency militias like the Sea Swallows or regulars in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam were daily engaging the Viet Cong. They should be expected to eat the same food, live in the same quarters, walk the same distances, and take the same risks as their Asian counterparts.

Having spent five months in the field with a myriad of Lao and Vietnamese troops as well as MAAG advisors, Dickey also knew the harm caused by the racist attitudes of Americans both on a policy and personal level. She’d gained substantial insight into the stereotypes that fed these attitudes, the logical fallacies behind them, and the fallout their perpetuation catalyzed.

Dickey addressed all these points head-on in the second appendix to her primer, entitled “An American Mythology* of Asian Defense.” The explanatory note to the asterisk read: “I have with difficulty resisted the temptation to substitute a forward-area term such as ‘hog-wash’ for the word MYTHOLOGY.” Anyone in any branch of the military would have understood that by “hogwash” she really meant “bullshit.”

The first hogwash-myth she addressed was that Buddhism prevented Lao and Vietnamese recruits from becoming effective soldiers. This she dismissed handily, writing, “the Pathet Lao which inexorably advanced against the Royal Lao forces month after month was almost all composed of Lao apparently uninhibited by killing.” The real difference, she argued, was their training, just like any other fighting force.

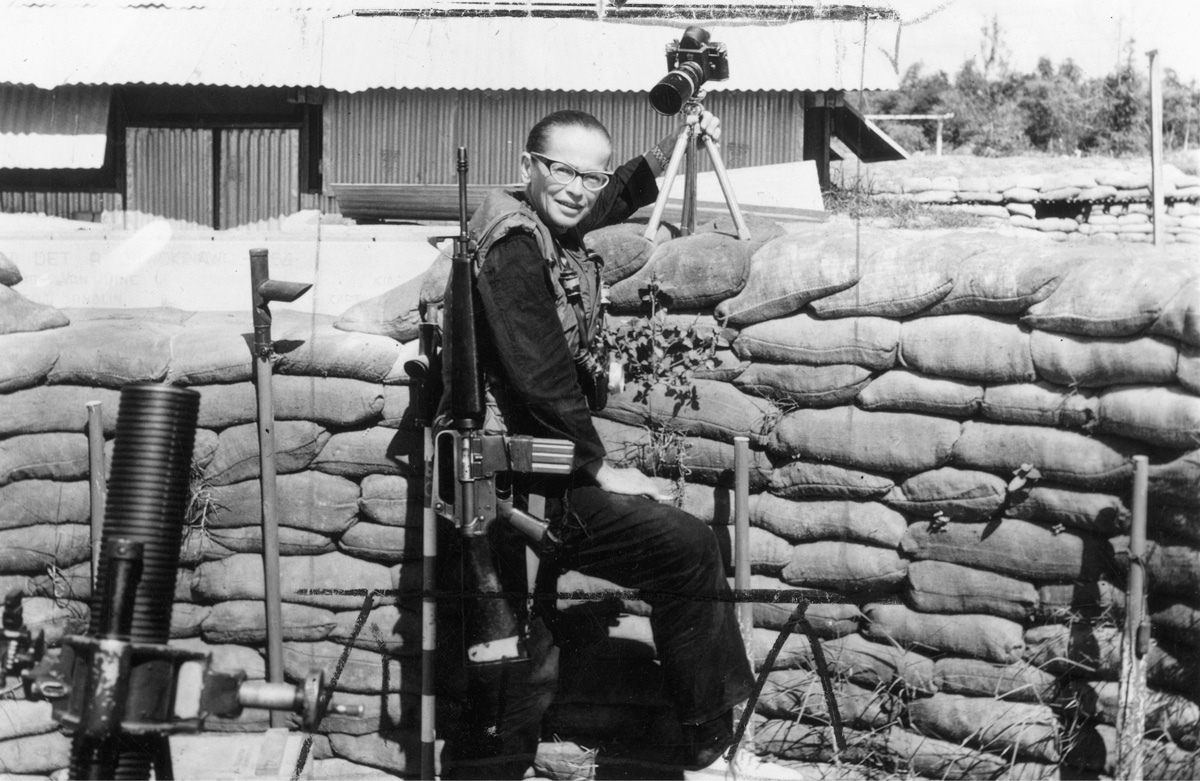

Dickey Chapelle in Vietnam—Though the Geneva Conventions prohibited journalists from carrying firearms, the realities of the Vietnam War required that they be able to defend themselves—as well as help the battalions they were embedded with—if the need arose. Here, Dickey is pictured carrying a semi-automatic rifle while embedded on the Vietnam-Cambodia border with the South Vietnamese Marines. (Wisconsin Historical Society, Dickey Chapelle, 1964, Image ID:1943; Reprinted with the permission of the estate of Dickey Chapelle)

Dickey additionally spoke to the idea that historical animus and language barriers prevented White American military advisors from effectively training Southeast Asian troops. For the past five years Dickey had felt nothing but welcome and warmth from numerous guerrilla forces from Algeria to Cuba to Vietnam. As such, Dickey knew that this animus, when it existed, could be overcome if Americans would only submit to the idea of a universal meritocracy. As she wrote, “This is another BIG LIE serving communism. Why do we believe it? Because, I think, of our distaste for thinking of any American in a situation where he is not automatically accepted because of his mere nationality and the cash in his wallet as a symbol of omnipotence the way we like to think Americans should be—but must earn respect by personal merit before he gets it.”

She further addressed the racist idea once famously espoused by General Westmoreland that “Asians just don’t have the high regard for the value of human life that we Americans feel.” The US military often cited the “human waves” tactic employed by Chinese troops during the Korean War as proof of this prejudicial concept. But Dickey easily countered this logic, “It is western military practice as well as Asian to employ human waves in war; what else is the classic infantry charge?” Iwo Jima and D-Day would come to the minds of those reading her words. “The ultimate contemplated waste of human life—the use of the nuclear bomb—is a real factor in the security plans not of Asia but of two non-Asian powers, Russia and the US.”

Drawing from her own experience in Fö Street Prison when she ceased to care about her own mortality, Dickey wrote, “I have never seen any evidence that the skin color or continental origins of anyone affects his respect for life. Scientifically, only pain (of exhaustion, injury, disease, hunger, disappointment) can reduce that instinctive respect.”

Realizing the full weight of this dangerous attitude, Dickey concluded her point with a personal experience worth quoting at length.

I have been in the presence of death among Asians very often. I have never known their reactions to be very different from my own if there was hope we could save a life; under that condition they eagerly did everything humanly possible just as Americans would. But there was a difference when it was clearly hopeless to try to save life. Then their reaction was to far better control the bitterness we all felt than I was able to do.

Once I remember there were tears in my eyes only as we loaded the body of a man who had just died fighting among us onto a helicopter. Later, the Asian sergeant told me:

“We liked you for crying. We think to show tears is unmanly. But you are a woman and we were glad you were there to cry for all of us.”

In so many words, Dickey once again told the US Marine Corps to soldier up to the level of those they dared deride at the risk of losing their own life and liberty.

The military establishment listened to her on a great many topics, incorporating a number of her suggestions, such as stationing MAAG personnel in the field and maintaining constant contact with their Vietnamese counterparts. Undoubtedly, others made these same points. But it was a small chorus and Dickey had the voice of a drill instructor. In the coming months and years, Dickey would give numerous briefings to top brass at the Army, Navy, and Marines. She gave lectures to new recruits on the basics and specifics of guerrilla warfare. The Marines included her writing in their counterinsurgency manual. Her photographs were often used in briefings for President Kennedy and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. After her presentation on “An American’s Primer of Guerrilla Warfare,” General Greene wrote her to say, “I think that you are a good Marine.”

But they did not listen to her in any discernible way when it came to creating a culture of racial equality within their ranks.

In truth, by the time Dickey had seen what she had seen and said what she had said, America’s racial bias had been so interwoven into its war plans that one voice could not have made a substantial difference. Instead, the opposite occurred.

On the same visit to Washington, DC, during which she briefed the Marine Corps, Dickey was recruited by the Human Ecology Fund. Outwardly, the fund invested millions in anthropological, psychological, and sociological research on a myriad of subjects largely pertaining to human behavior. Headquartered at the Cornell University College of Human Ecology, the fund ran satellite programs at twenty separate institutions, including George Washington University, where Dickey signed a contract for “$50 dollars a day and travel expenses” for work on unspecified “research problems in areas of your competence.”

Only two clues remain as to the nature of her work: a pamphlet advertising her lecture on methods of resisting communist attempts at brainwashing, given at a Human Ecology Fund conference; and a letter indicating she submitted a treatise on the importance of supporting a free press within a democratic society. In both cases, Dickey seems to have assumed her work would be used to expand and protect the constellation of rights enshrined in the US Constitution and Bill of Rights while informing the evolving field of international law with the ultimate goal of expanding the borders of the free world. Indeed, the vast majority of those who received grants and contracts assumed similarly benign, if more banal, motives behind the fund since they were given no reason to suspect otherwise.

In reality, the Human Ecology Fund was a front for the research and development of MK-Ultra, a CIA-led interrogation enhancement program that used psychotropic drugs, electroshock, and psychological torture to illicit confessions from detainees across multiple conflicts during the Cold War. None of the researchers that received Human Ecology Fund grants or contracts, Dickey included, were told that their research would be used for these gruesome purposes. Nor would any have cause to suspect these covert and criminal intentions with Cornell University as a front. Not until an investigative report by The New York Times in 1977 was the scope and scale of the Human Ecology Fund revealed even in part. But by then the CIA had purposely shredded the majority of the paperwork pertaining to the development of MK-Ultra through the fund, forever concealing the extent of this program.

Washington had turned America down a dark road that Dickey would follow as far as she could.

About the author—Cultural critic and historian Lorissa Rinehart writes about art, war, politics, and the places where these discourses intersect. Her writing has recently appeared in Hyperallergic, Perfect Strangers, and Narratively, among other publications. She holds a master’s of art from NYU in experimental humanities and a bachelor’s of art in literature from UC Santa Cruz. First to the Front is her first book.

For more information visit www.lorissarinehart.com or Instagram @Lorissa_Rinehart

Leave A Comment