MACV-SOG

One-Zero School

Part II in the Series:

School Development and Assignment of Class One

By Travis Mills

Originally published in the April 2018 Sentinel

Editor’s Note: If you missed part one of this series, click here to read it.

I spent 31 days on the Sanctuary and then returned to FOB 4. When I got back to camp it was noon meal time. It was a bittersweet reception. Seeing old friends and learning of the ones that were gone. My old hooch was now occupied by new guys and all my stuff was in a foot locker in supply waiting to be shipped back to the states. I was assigned a room in the transient quarters. The next day I went to the S-1 and S-3 to see about getting back on the team and getting back in the game, but life had other plans.

I had been able to talk my way out of the hospital and back to camp rather than being sent to Japan for rehab. So I was assigned to work with Maj. Toomey until I was recovered enough to get back on a team. After a couple of weeks, Maj. Toomey said SOG Headquarters in Saigon had sent a levy for a One-Zero qualified officer to start up a “Recon Team Leader’s Course” (One-Zero School) in Camp Long Thanh. He told me this would be a good assignment, give me time to “heal up” and in couple of months come back to the FOB to get back on a team.

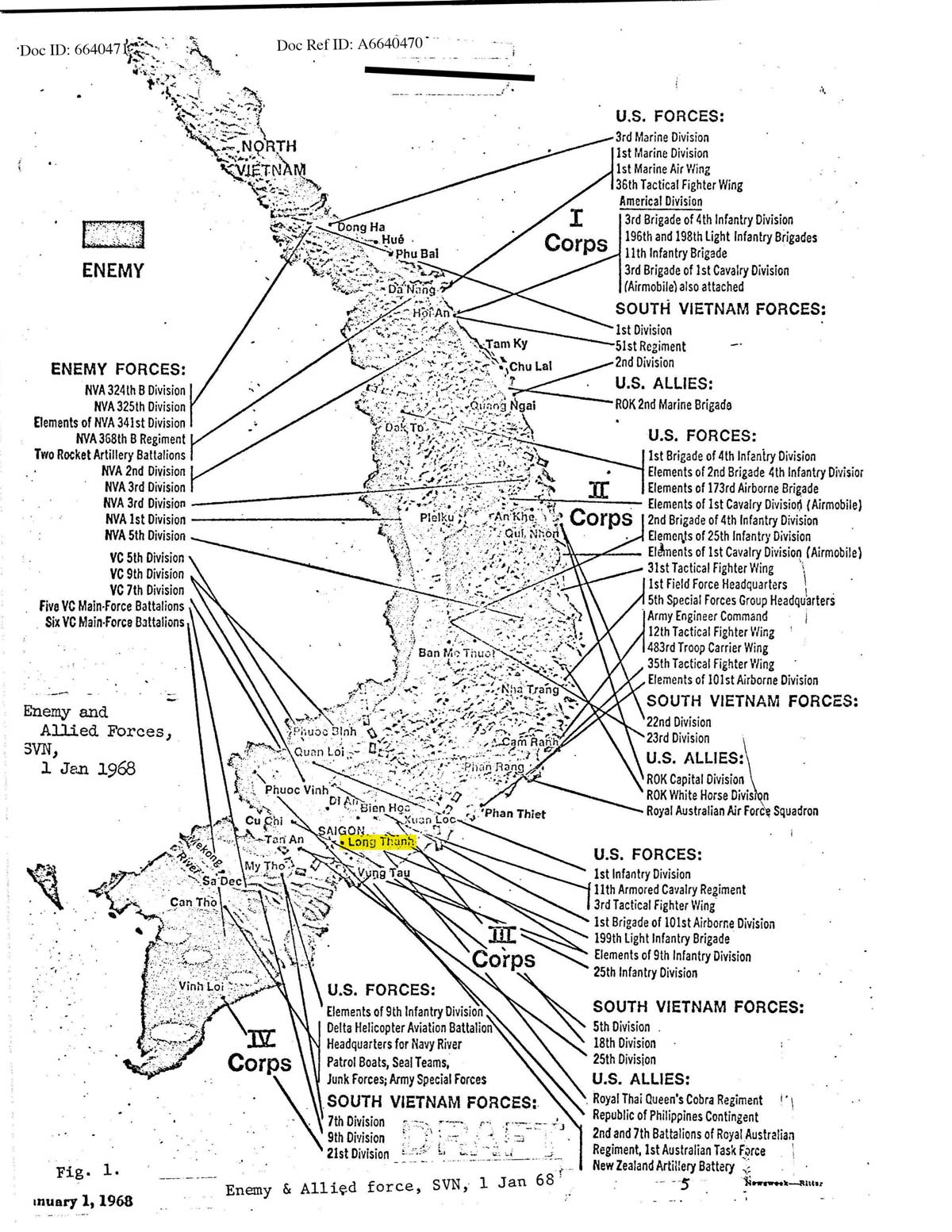

The next day I was on the “milk run” to SOG Headquarters I was given a quick briefing by Col. Cavanaugh (Chief SOG) and Col. Johnson (Chief OP 35). Basically, SOG was in a difficult position because of recent heavy losses of experienced One-Zeros and increased demands for missions. The vast majority of the replacements had no SOG experience and there was not enough experienced One-Zeros to train them, let alone field as many teams required by the demands from MACV. The classic Army solution was “Start a School”. Then I was handed off to a MAJ in the S-3. He gave me a US Army Manual on Patrolling and a general outline for a 21-day “patrolling course”. The course was to be conducted at Camp Long Thanh and I would be assigned one experienced One-Zero or One-One from each of the FOB’s as instructors. I would go to Long Thanh the next day and the first group of students would arrive in 3 weeks.

Map from PARTIAL REPORT: U.S. Army Security Agency Southeast Asia Cryptologic History, Chapter 6 - the January 1968 Communist Tet Offensive (NOTE: Full Report is Unavailable).

Long Thanh

The next day I was escorted to Long Thanh by the MAJ from S-3 and introduced to the CO and the OPS Officer as “the person who will be organizing and running the new team leader school.” By the look on their face, I had a feeling this was the first time they had heard of this new school. With that, the MAJ stated he had to leave in order to get back to Saigon before it got dark and the road closed. After he left, the CO and S-3 began asking all kinds of questions about who, how many, when, how long, about logistics (food, lodging, training materials, ammunition), etc., etc. I showed them the Patrolling Manual and the one page training outline. We all agreed we had better have a long meeting tomorrow. I was given a bunk the transient quarters and as I lay down that night my only thought was “What in the hell have I gotten into?”

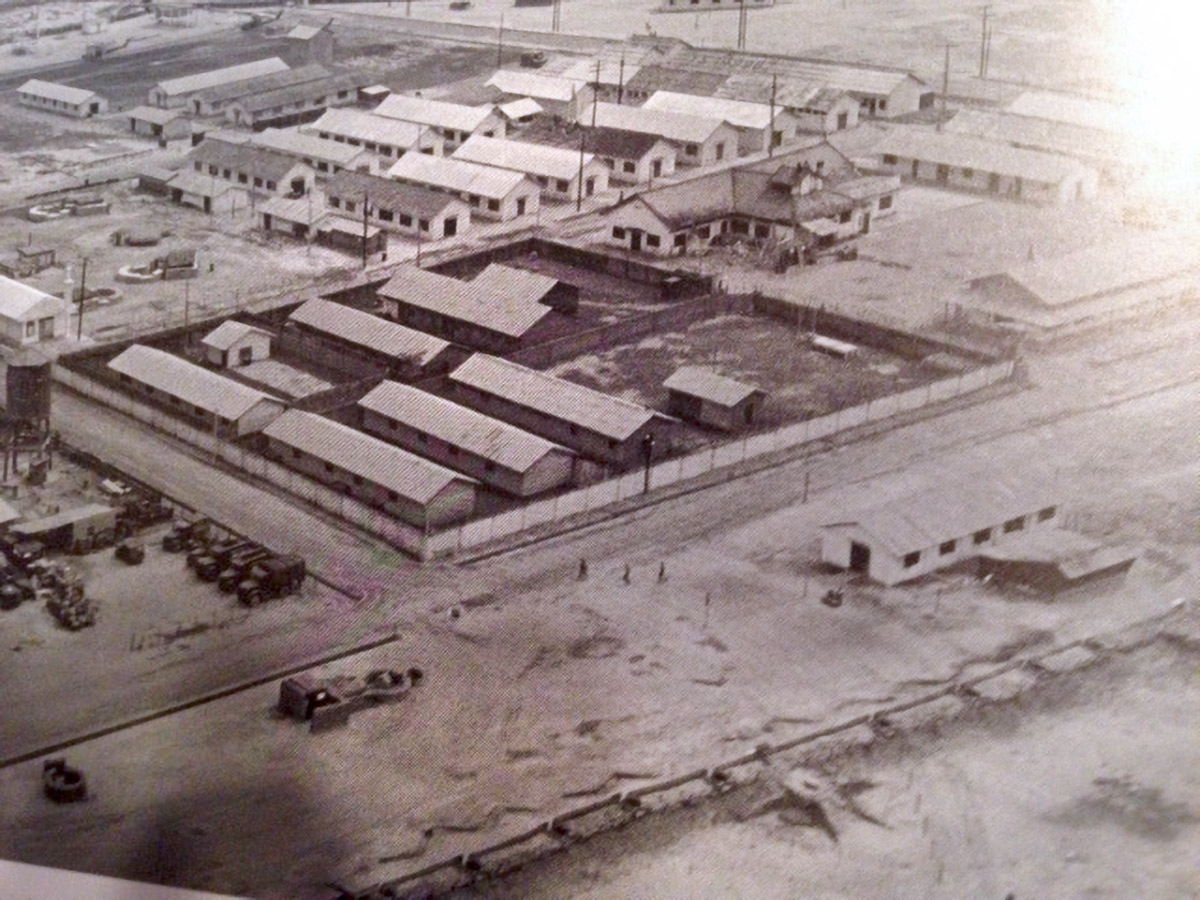

Camp Long Thanh was a very unique camp. On the 5th Group Organization Chart it was listed as B-53. It was about 35 miles SE of Saigon about 5 miles off of Hwy 15. It was rumored to have been established by the French prior to WWII, supposedly it had been occupied by the Japanese during WWII and reoccupied by the French after WWII until their withdrawal from Viet Nam. Upon their departure it was taken over initially by the CIA, and eventually by MACV-SOG. From the very beginning it had always been a highly secretive site and occupied by very high level intelligence units. The camp was quite large and very compartmentalized. There were several “compounds” within the camp, that unless you had the correct clearance and/or need to know, you didn’t ask questions or try to enter. It was home to the projects “Borden”, STRATA, as well as many others never acknowledged. There was a small airstrip just south of the camp where a steady stream of C-130 and C-123 “Blackbirds” picked up and dropped off non-descript teams and supplies. Everyone in the camp wore sterile uniforms (unmarked tiger suits), and when outsiders visited they were required to turn their jackets inside out to mask names, ranks, etc.

Due to the camp being established so long and occupied by these “secret organizations” with very substantial “discretionary funds”, the accommodations were quite extraordinary for a “combat zone”. If you were permanent party in this camp you had an individual, air conditioned room, with clean starched sheets. The dining facility was one of the best in Viet Nam. The chief cook had been the “chef” at the embassy, but he had two draft aged sons. So one of the previous CO’s made the offer if he would come to the camp, the camp would hire his two sons as part of the security staff, which would give them a complete deferment of the Vietnamese Draft, and they would be assigned temporary (permanent) duty as his KP assistants. As the saying goes; “it was an offer he couldn’t refuse.” The mess sergeant made regular trips to the Saigon docks when the Navy ships were in with a truck load of “War Trophy’s” (VC Flags, VC Sandals, etc. — made by the camp sew-girls, sprinkled with chicken blood and a few bullet holes) to trade for the Navy rations. The end result: Life was good at Camp Long Thanh.

Initially it was a strange relationship. Long Thanh was an OP 34 camp and I (and the instructors coming later) were from OP 35 and definitely considered “outsiders”. I at first, and the instructors when they arrived, were given very specific guidelines and restrictions on where we could go around the camp and what we could do, and especially don’t be asking any questions that didn’t specifically pertain to the One-Zero school. Even though this One-Zero school seemed to be pretty high on OP 35’s priority list, it didn’t seem too high to the OP 34 list. I was told in Saigon the camp would provide logistical support, i.e., training facilities, materials, ammunition, and transportation. The S-4 told me to submit a list of what I needed and they would forward it to SOG S-4. SOG S-4 didn’t seem to have a very high priority on our requests, so we received only about 30% of the materials requested. I was told this is a new project and supplies are limited, so you’ll have to make do with what you’ve got.

Camp Long Thanh (Courtesy Travis Mills)

Instructors Arrive—Their Training Begins

Near the end of the first week the instructors started showing up at the camp. They were all experienced One-Zero’s or One-One’s. Just like me, they were told to go the airfield, get on a blackbird and get off at Long Thanh. Most of them had been told very little about the project and were also told they were only “on loan” to the school for a couple of cycles. As a result no one had any orders other than the “special travel orders” from the FOB’s and the infamous “get out of jail free” card. Those “special travel orders” identified the bearer as a member of MACV Studies and Observations Group, a highly sensitive unit and verified the bearer had all the sufficient security clearances and authorization for travel via the “Blackbirds” and/or Air America. Most of them were not very happy to be there, they wanted to be back at their FOB with their team. A couple of them had an injury and were sent to the school while they healed up. The only thing that made it somewhat palatable was the opportunity of an occasional trip to Saigon.

We were provided a barracks type building that was previously used by the STRATA Teams. We used half for bunks and the other half as a work area for class preparation. In the days (and nights) before the instructors arrived I had been racking my brain to come up with a training program that would provide “keep you alive” information and mission essential skills. I thought back to my first days on a recon team: What knowledge and skills would I liked to have had that first time I jumped off that Kingbee 20 miles from nowhere?

We spent the first two days just sitting in a circle getting to know each other and formulating a plan. I told them, “You guys are still 1-0’s, you’ve just got a different mission for a little while. These guys we’re getting are new to SOG. You guys, better than anyone, know that Prairie Fire and Daniel Boone recon is an entirely different animal. There are no manuals — it’s all acquired knowledge from being on the ground and coming back alive.

Our job is to teach them that knowledge and those skills so when they go back to their FOB, they can be an immediate asset to their team. The teams now are so heavily committed the 1-0’s don’t have the luxury of spending a week or two to train new guys — they have to be ready and able to contribute within a few days of being assigned to a team. We will have two weeks here — then we all go to FOB 2 for the ‘final exam’: to be assigned a target and launched. FOB 2 agreed to this plan because their teams are over committed and 3 or 4 extra teams will help relieve some of the pressure and give their teams a much needed break. These will be real targets, so take your side of the training very seriously because these “students” will be your team.

When you come back from the mission, if you give your approval, the “students” will be given a handshake, a pat on the back, a Zippo lighter with the SOG crest, a very sincere “Keep Your Head Down”, and a ride to the airfield to catch a blackbird back to their FOB. We come back here for a one week break to get ready for the next cycle of students to arrive, then we do it again. How long will this school last? I don’t know. Col. Johnson, Chief of OP 35 told me we will continue until there are no more new guys to train. At the current rate of our losses, we may be here quite some time. “You will be here until your FOB sends a replacement.”

With that piece of business out of the way, we launched into a brain storming session of what are the most critical subjects and skills they need to learn and how we are going to get it all done in two weeks. Each one had their own opinion of what was most important as well the differences in operating procedures between the Prairie Fire and Daniel Boone AO’s. At the end of a very long day, we had compiled a preliminary list of subjects and tasks.

The next day we began to formulate a training schedule. Because the vast majority of the “students” will be new to SOG, we felt it extremely important that the very first thing was to emphasize that our “business” is vastly different than anything they have ever seen or been involved in before. This is not just some glorified long range patrolling. The standard mission is 7 days, but very few last that long. Once you get off that helicopter the only “friendly’s” are the other members of your team and Covey (a forward air controller dedicated to SOG). You and your team immediately become one of the most hunted groups in the country. The North Vietnamese take it so seriously, there is a real bounty on the SOG teams and they have a special, highly trained unit whose sole mission is to hunt down and destroy SOG teams. You will always be outnumbered. Sometimes it’s only 2 or 3 to 1, but it can rapidly and easily escalate to 100’s to 1. Once the enemy knows you’re in the area, they will devote entire regiments to find and kill you.

You will be operating up to 17 miles deep into enemy territory. And because we do operate so deep across the border, once the helicopters insert you they are only able to stay in the area a short time, then they have to go back to refuel and rearm. If you get in trouble, it can take up to an hour before they can get back to you. There is no mortar or artillery support. In Prairie Fire you have air support, but in Daniel Boone you only have helicopter gunship support. In some areas there is communication through a relay site, but as a general rule, Covey is your only communication and your lifeline. Running recon is a tremendously hazardous business, and if there is a secret to success and survival, it’s knowledge and training. Every one of these instructors are experienced 1-0’s or 1-1’s. Our mission over the next two weeks is to share as much of that knowledge and experience, both the successes and mistakes, so you can make a significant contribution to your team. Your “final exam” will be a mission on a real target. This is very serious business, so pay attention and train hard.

Jon Cavaiani (MOH recipient), lower right, when he came through 1-0 school at B-53 (Photo by James [Jones] Shorten, used with permission)

Topic One: Define the Mission

Once we had their attention, the next subject was to define the mission of SOG. The primary mission is gathering intelligence. There are some direct action missions, but those are primarily for the Hatchet Forces. Your ultimate goal is to be inserted into your target area, spend your time gathering the intelligence and being extracted and no one ever knowing you were there. Unfortunately that rarely happens. Although your mission is not to go in and “shoot up” the place, you and your team will be among the most heavily armed groups in the country. If you are discovered by the enemy, your survival depends on being able to win that fight even though you’re heavily outnumbered and outgunned and a long way from help. Some of the advantages you have are:

- stealth;

- a small team (6 to 8 men) can move fast;

- intensive training and

- precise team execution.

By stealth we don’t necessarily mean slinking around in the shadows, but more of being able to move through the area silently and invisibly. You will be carrying a lot of equipment, weapons, etc. Almost all of them are made of some type of metal and/or hard plastic. Unless properly prepared, every time you move or take a step, these things make noise. As a 1-0, it is your responsibility to ensure every member of your team has sufficiently “silenced” his gear. One of the first things is to get rid of is the standard rifle sling. It and the attachment swivels make lots of “hard noise”. Remove the sling, and secure or remove the sling swivels. All other equipment that can come in contact with another hard object must be secured or cushioned so it doesn’t make hard noise. Your movements and “noise” must blend with the natural sounds of the jungle and it is essential that you hear “them” before they hear you.

Not only must you “silence” your gear, you have to communicate silently. Once you’re on the ground, talking must be held to an absolute minimum. You must have your team so well trained and drilled, that 95% of communications can be done with hand and arm signals. The first time you are lying beside a trail and observe an NVA unit move by, you will be amazed how much noise they make and how far you can hear them coming. It will totally confirm the importance of silence in your movements.

The other part of stealth is being invisible. It is obvious that means blending with the surrounding environment, and most importantly covering your trail. It is almost impossible for 6 or 8 men, carrying very heavy loads (rucksacks & weapons), to move through the jungle and not leave evidence of their passing. The “tail gunner” is one of the most important members of your team. He must understand the importance of covering the trail and how to remove and/or camouflage the signs of your passing.

In our operational areas the enemy employs highly skilled trackers. These are usually people who are native to the area and extremely familiar with the local terrain. If they can pick up your trail and determine the direction of travel, their familiarity of area will allow them to use a parallel trail to get ahead of you and assist the local unit in setting up an ambush, and just lie in wait for you. As a general rule they will not follow your trail directly or too close. They will travel off to the side and far enough back to be out of sight, but within hearing distance. If they can’t get ahead of you, they will track you to your RON site, then one will go back and guide a larger, heavily armed unit to overrun your RON site. You have to always be aware of the possibility of trackers and take the necessary precautions.

On the other side, even though there’s a good chance you have trackers, don’t let that panic you into taking unnecessary risks. You may occasionally run into tracker dogs. The dogs are not as big a threat as the human trackers. The dogs are usually not well trained and tend to bark, alerting you they are there. There are several things to deter the dogs such as powdered CS, pepper mixed with dried blood, etc. During the movement techniques phase, we’ll talk about ways to evade, elude, and possibly eliminate trackers. Although it may be close to impossible to not leave some evidence of your passing through the area, the important objective is to make it as difficult as possible for the enemy to detect your trail. The more difficult you make it, the more likely they will make an error and if you know they are there you can take appropriate actions.

Although these were only three of the many tragic events within SOG, they were significant teaching tools to emphasize to the students the seriousness of our operations. They drove home the point that your team will be hunted like animals and in order to survive you have to be at the top of your game every minute you are on the ground. Contrary to popular belief, the enemy that is hunting you is very, very good, extremely dedicated and unrelentingly persistent. If there is just one thing you take away from this course, it should be that just one minute of inattention can result total disaster.

RT Mamba from CCN on a prisoner snatch mission (SOA-B53) (Photo courtesy James [Jones] Shorten)

Topic Two: Gear—Load Your Fatigues

The next topic area was gear. The choice of uniforms is almost unlimited. The only thing that is “chiseled in stone” is that you will be completely sterile. No dog tags, no ID Cards, No Jump Wings, No Patches, No Name Tags and/or Nickname Tags, etc. At this time in the war, there have been enough US uniforms and weapons lost, captured, sold on the black market, etc., that just because you have one of those items, the State Department can still have plausible deniability. Most of you will not immediately be assigned as a 1-0. The vast majority will go to an existing team as a 1-1 or 1-2. The other team members will be full of advice about uniforms and weapons and other gear. Almost everyone has their own personal preference, but many prefer the standard US jungle fatigue uniform. It has lots of pockets, it dries quickly and is pretty rugged and is readily available. All the FOB’s have a sew-shop, and almost everyone will have their field uniforms modified with extra pockets, compartments, and appendages. Again, the 1-0 will have plenty of advice on what you add and how to utilize it. The boots of choice are the standard US issue Jungle Boot with the nylon tops. They’re light, rugged, provide good ankle support and most of all they dry quickly.

Keeping your feet and your other body parts as dry as possible will be a top priority. It’s a highly debated issue, but many of the experienced team members chose to not wear underwear or socks in the field. It rains a lot in the A/O’s and most team members don’t carry any type of rain gear, so you’re going to get wet. You are going to spend days in wet clothes, whether it be from rain or sweat, combined with accumulated dirt, grime, etc., and you will be prone to develop a rash. The standard issue underwear has a tendency to bunch up and exacerbate the rash and in that hot, humid, dirty environment, pretty soon you have a good case of the classic “crotch rot”. It can get extremely uncomfortable and you will likely fight it for the rest of your life.

Continually wet feet can be a tremendous problem. The skin begins to get the “prune” appearance, and continued walking, running, etc. causes the skin to begin to flake off and develop into areas of raw tissue. Again, in that environment, infection is rampant. Many of the “old hands” go without socks, because they retain the moisture, both sweat and rain, and increase the chance of “trench foot”. Sure you can wear socks, and many team members do. You just have to be continually aware of your feet and change socks as often as possible. Also, you can’t decide the day before the mission to not wear socks. You have to condition your feet, by going without socks all the time in camp and when training. It will take a few weeks to get them really tough and develop callouses in the right spots. Once you have your feet conditioned and you’re wearing the jungle boots with the air vents and nylon tops, you will have a much lower chance of developing foot problems. But, whatever you decide to do, be aware of these potential problem areas and take the necessary precautions to prevent injuries and/or infections.

When you start putting your gear together, you start from the inside out. Once you’ve decided on the basic uniform, you build from there. What you carry in or on your basic uniform is your absolute last line of survival. It means you’ve ditched your rucksack and web gear and all you have left is what you have in your pockets.

The first thing in your fatigue pocket is the URC-10 Emergency Radio. This is your last line of communication. It puts out an emergency signal on the guard frequency that is monitored by all aircraft.

The next thing is a compass on a piece of suspension line around your neck. In one of your breast pockets is your operational map and your mission KAC code sheet. The operational map only covers your current A/O (usually 16 to 20 grid squares). It is covered with acetate so you can annotate it with grease pencil. Again, it only covers your current A/O — it’s a need to know situation. If you have no idea if there is anything going on in the grid squares around your A/O, you can’t compromise anything or another team, no matter how much they beat you. The KAC code sheet is a 5X5 matrix of colors and numbers with each square a predetermined response.

Each team has a unique KAC for a mission and covey has a copy of each individual team’s KAC. An example would be once a team is on the ground, within 10 minutes the 1-0 will call covey with a Black 23. On their KAC sheet that’s a “Team OK!” These KAC sheets change with each team and each mission. After mid-1968, and the introduction of RDF along the “Trail” minimum time on the radio was essential to avoid team detection. Also there was an “emergency KAC code”, that was a minimal code committed to memory by the 1-0 and covey. This was used in absolute last ditch commo and used with the emergency authentication code. That code was committed to memory and only known to the 1-0, the S-3 Briefing Officer, and Covey. If you make a mistake on the authentication code, the next thing you will see is a 2.75 WP rocket marking your spot followed by a 250 lb. bomb, or a napalm canister, or 20mm cannon fire! So make sure you remember the emergency authentication code – it is for MEMORY ONLY – DO NOT WRITE IT DOWN!!

In one of your other pockets is your emergency medical kit. That contains morphine, compress bandage, cravat (tourniquet), marching pills (amphetamines), surgical thread and needles, and water purification pills. Again, these are last ditch emergency supplies – you have dropped or lost everything else and severely injured and this is what will get you the last few hundred meters to the LZ. In my right breast pocket I had a pen flare. On a piece of suspension line tied to a belt loop was a Swiss Army knife or a standard demo knife in the right trouser pocket.

In the two big pockets on the pants you put one indig ration in each pocket. The indig ration was a bag of dehydrated rice with some vegetables and some type of protein (squid, or shrimp, or mystery meat). You put water in the bag and put it in your pocket to “cook” with your body heat for a few hours. You always have two bags cooking. Once you use one, you put another one in the pocket to replace it. The normal situation was to carry one bag per day of anticipated mission, (Very Important: always have a bottle of Tabasco Sauce – this stuff is totally inedible without Tabasco Sauce) YOU NEVER COOK IN THE FIELD! The only reason you carry this food is because you have to have some type of food to maintain your energy. You are not on a family outing or picnic, this is not food to enjoy or savor — it’s only function is to provide you the necessary energy to accomplish your mission.

A team’s most vulnerable position is when it’s taking a chow break. For some reason, humans get so complacent and/or distracted when eating, they have a total tendency to ignore their surrounding situations. NEVER relax during a chow break! NEVER let more than half of the team eat at a time — the other half MUST be on full alert.

The last thing you must have after you have dropped everything else is some water. You can survive several days without food, but only hours without water. You have some purification pills in your emergency medical kit, so even if you have to skim the scum of the top of a pond, it can sustain you and maintain your energy level to continue you evasion and escape effort.

The next thing is a signal mirror. You put it on a loop of suspension line through a button hole on your shirt, and carry it in one of your breast pockets. And finally, if you wear a hat, we recommend a “stingy brim” hat (the FOB sew shop will know how to do it). Line the top of the hat, with a piece of “Air Force Emergency Panel”. If you prefer to wear something other than a hat, i.e., cravat, or whatever, carry an emergency signal panel in one of the big pockets of the pants.

Conrad “Ben” B. Baker, inducted into the Special Forces Regiment as the 12th Honorary Member on April 27, 2017, holds a box of Indigenous Rations used by Montagnards, Rhade, Vietnamese and other indigenous personnel during the war. Amongst the many achievements Baker accomplished as the deputy director for the Counterinsurgency Support Office at served SOG and other agencies during the Vietnam War was the research and development of specially designed rations for the indigenous troops who support Special Forces and other agencies during the Vietnam War. Under Project PIR, Baker estimated that 66 to 86 million Indigenous Rations were purchased and provided to troops supporting the U.S. war effort. (Photo Courtesy of George Eleopoulos, SFA Chap. 23)

Web Gear

Once you’ve got your fatigues loaded, the next level is your web gear. A lot of the RT members really liked and preferred the BAR Belt (WWII Browning Automatic Rifle). Each pocket on the BAR Belt would hold 5 CAR 15 magazines, plus it had open space for grenades, canteens/water bottles, grenades, etc. It was a great piece of equipment, but because of being WWII vintage, the availability was quite limited. (When I was in the Hatchet Force I had a BAR Belt, but when I was moved to an RT, I left it with my replacement platoon leader and opted for traditional web gear with canteen covers for ammo pouches) Even though BAR Belts were preferred, the traditional web gear is the norm for most RT’s.

The most common ammo pouch is the traditional canteen cover. You can put 7 CAR 15 magazines in each one. You can put 5 magazines vertical and 2 two laying on their side on top of the 5. On the standard web gear you can easily put 4 canteen covers (4 X 7 = 28 mags X 18 = 504 rounds + 1 mag in the rifle = 522 rounds). We put 18 rounds per magazine because you didn’t want to overstress the magazine spring. If the spring gets weak, it causes a misfeed and a potential jam. The magazines are loaded facing down, bullets out, so rain and debris can drain out, and we put tape on the bottom of the magazines so we have a tab to pull them out easily. When you come back from a mission and get a 2 or 3 day stand down, get the entire team together and spend 1 or 2 hours, unloading all the magazines, cleaning the rounds, cleaning the magazines, cleaning and oiling the springs. It’s only a couple of hours, but it can mean the difference between life and death on the next mission. You are only one misfeed from disaster.

Next on the belt is water: one standard canteen on each side. As stated before, you can survive days without food, but hours without water. On the right side, I carried a canteen cover with M26 hand grenades. On the left side I carried a canteen cover with 2 WP grenades. That left one space, and I carried a canteen cover with the standard medical/first aid supplies.

On the left shoulder strap I taped a strobe light (the cover was colored blue with magic marker). Underneath that I had a yellow smoke grenade.

On the right side I had a 6” Buck Folding Knife, and underneath that a WP Smoke Grenade.

Load Your Rucksack

Now that we’re finished with the web gear, we’re at about 40 lbs. of gear, but now we get to the rucksack. One of the first decisions to be made is who carries the radio. Some 1-0’s prefer to carry the radio so they can communicate directly rather than relaying through another team member. Others prefer to have the 1-1 or 1-2 carry the radio. They feel that while the radio operator is occupied with the communication, it allows the 1-0 to concentrate on the immediate situation and directing the team. It all comes down to what is most comfortable for each 1-0. If you are the one who will carry the radio, it’s the first thing that goes in your rucksack. The PRC-25 weighs about 25 lbs., and takes up quite a bit of room so you will be somewhat limited in what else you can carry.

Your assigned mission will have influence on what equipment you take. Once the equipment list has been done and distributed within the team, then you can load your personal gear. Mission essential items are the first to go in. Extra magazines, claymore mines with the firing device and connecting wire, toe popper mines, a collapsible canteen, C-4 (if needed), pre-cut time fuses for the claymore mines and/or C-4, a few extra frag and smoke grenades and extra batteries for the PRC-25 and URC-10, a box of blasting caps and the PEN EE camera.

The only creature comfort items I carried was an indig poncho and a long sleeve sweater. The indig poncho was only about 2/3 the size of the standard army poncho, it was light weight nylon and made very little noise. When you’re wet, which was most of the time, it gets very cold in the mountains in the wee hours of the morning and the sweater helps make those long nights bearable. These were folded and put in a pocket on the rucksack that provides some cushioning between your back and the radio.

The last thing that goes in is food and a C-Ration packet of toilet paper. I carried the indig rations, 2 in my fatigues, and 2 in the rucksack. That would last 4 or 5 days. I had rather risk being hungry, than running out of ammo or not having a back-up battery for the radio. On the outside of the rucksack I carried a Swiss seat rope on one side and an indig machete on the other. At the top of the rucksack where the straps attach to the “bag” I had a snap link attached. This was to be used if we had to come out on McGuire rigs or strings.

DO NOT take heat tabs or cigarettes to the field. NEVER cook or smoke in the field. If you have heat tabs in your rucksack, it’s a tremendous temptation to make a cup of coffee on those long, cold nights. If you don’t have them, there’s no temptation. American cigarettes have a unique odor and carry a long way in the jungle. Again, if you smoke and you have them, it’s a tremendous temptation and if you smoke in the field, dying of lung cancer will be the least of your worries.

Once you are loaded out, the fatigues, web gear, and rucksack you will be carrying about 70 lbs. of gear, etc. What you carry will evolve as you get more experience and re-evaluate what works best for you.

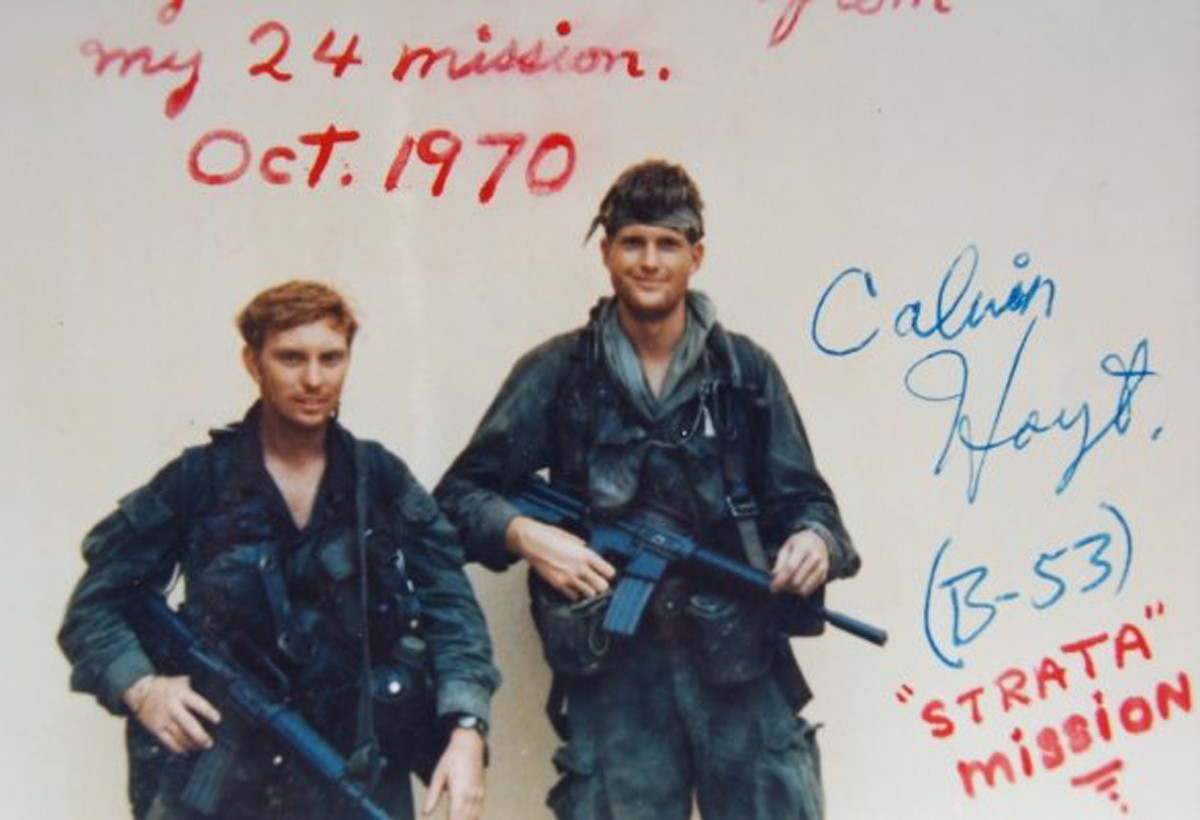

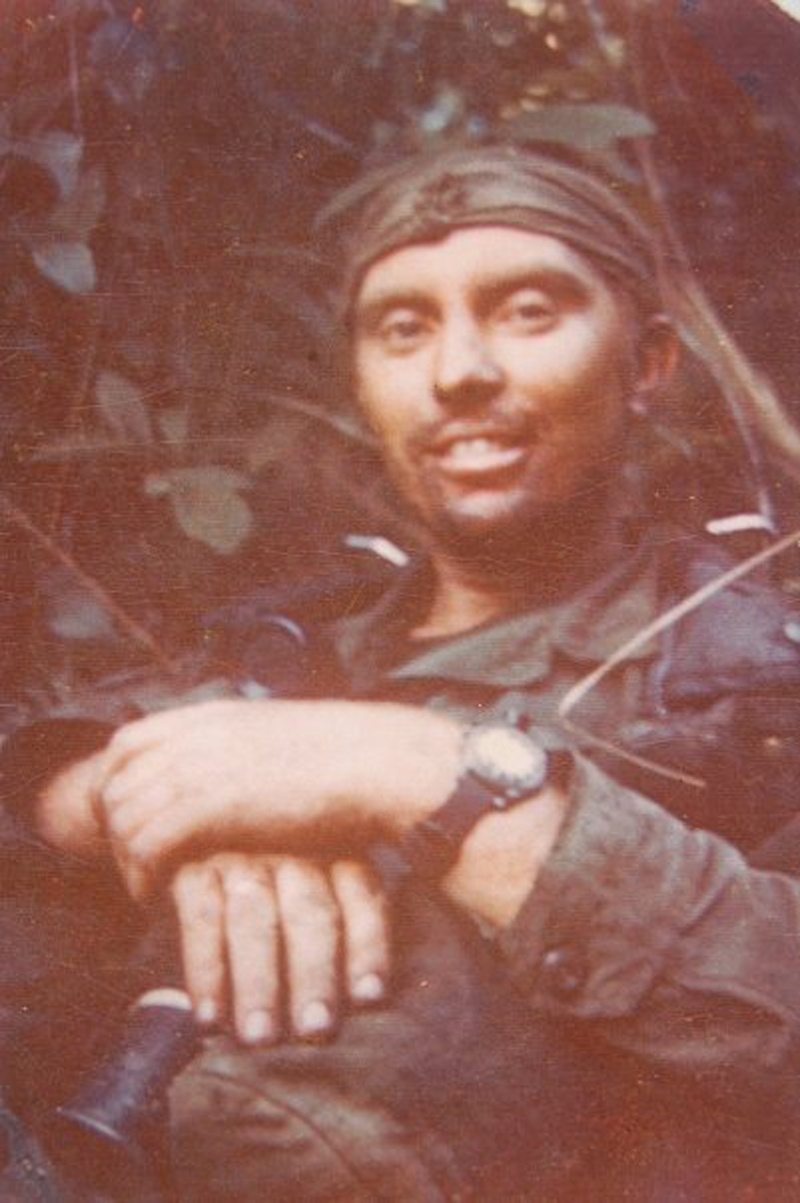

Jim Shorten, left, and Calvin Hoyt, at right, just returned from a mission, SOA-B53, which involved training captured NVA that were coming over to our side. (Photo courtesy James [Jones] Shorten)

SOG Green Beret SSG James H. Shorten (Jones) has generously provided many of the photos for Part 2 and 3 of Travis Mill’s story. He was Training Officer at the One-Zero School during July through Oct 1970

Click here to read Mike Keele’s report of Jim’s recounting of his Bright Light mission out of Dak To to recover the crew of an F-4 Phantom as a memorable guest speaker at our November 2018 Chapter meeting.

You will also find links to a seven part series about Jim Shorten by John Stryker Meyer originally published on SOFREP in 2017.

Topic Three: Weapon

The next thing is your weapon. The weapon of choice is the CAR 15. It is very versatile, has good knockdown power, and you can carry lots of ammunition. SOG has access to various weapons, i.e., the Swedish K, the British Sten, the old WWII Grease Gun, AK 47, the M-79 Grenade Launcher, and the silenced 22 Cal. Pistol, just to name a few. During your time here you will do familiarization firing of these various weapons. The all have pros and cons, and it’s really up to you and your team leader as to what you carry. Sometimes the mission will influence the choice of weapon for some members of the team. Whatever weapon you select, make sure you are thoroughly knowledgeable of its operation and maintenance. Many 1-0’s and team members opt to carry a modified (sawed off) M-79 Grenade Launcher in addition to their primary weapon. The stock is sawed off and modified into a pistol type grip. Two or three of these on a team can add a lot of firepower and shock effect.

Topic Four: Team Organization and Training

The next subject area was team organization and training. Again, there are no concrete rules on team organization other than the 1-0 is the BOSS. His word is law. Up until a short time ago, all 1-0’s had at least 5 missions as a 1-1, most had close to 10, and a recommendation from his former 1-0 to be assigned as a 1-0. Experience, not rank was the primary qualification factor. When I joined an RT as a 1-1, I was a 1LT, my 1-0 was a SSG, but as long as I was a member of that team he was in charge until he rotated and recommended that I be moved up, otherwise I would have remained the 1-1. As a result of heavy losses and increased operational requirements, we don’t have that luxury any longer. Many of the 1-0’s today only had the opportunity of 2 or 3 missions before being moved into the 1-0 position. But even so, he is still in charge. He may ask your opinion or input during training and mission prep, but on the ground in a firefight is no place for a tactical discussion.

The 1-0 will organize the team, set up the order of march, and assign specific duties. The organization of the team will be a reflection of the 1-0’s experience. Unless the mission dictates differently, most prefer a six man team. Under normal circumstances of altitude and lift capability, the entire six man team can be inserted and extracted on one chopper. Usually, the point man will be the most experienced indig team member. Obviously he will be first in order of march. Some 1-0’s prefer to be next in line with the M-79 man third for increased firepower during an initial contact. Fourth in line will be another indig, next will be the 1-1, followed by the tail gunner, the second most experienced indig team member. Because of the importance of the tail gunner in covering the back trail, some 1-0’s prefer to have the 1-1 as tail gunner. Most teams will have 6 to 8 indig members which allows for sickness, injuries, etc..

All members continually train together which allows substitution without degrading the expertise level of the team. The indigenous personnel who work for SOG are not part of the VN military. They are Yards (Montagnards), Nungs (Chinese), and/or Cambodians (KKK), and basically are mercenaries who work strictly for SOG and are very well paid compared to the VN military. They come from tribes of highly respected traditional warriors and are fiercely loyal to the Americans.

The 1-0 will organize and supervise the team training. If you are not on a mission, you are training. If there is such a thing as the “magic bullet” in recon, it is continuous and intense training and flawless execution. You will constantly be practicing IA Drills (Immediate Action Drills), both dry run and live fire. These are primarily actions taken immediately upon contact. Over time, numerous IA Drills have been developed from the experience of literally hundreds of contacts, and what has proven to provide the team with the best chance of surviving the encounter. During this course you will go through some of the major and/or standard IA Drills, e.g., Frontal Contact, Flank Contact, Rear Contact, and LZ Contact.

Each of you will rotate performing the duties of each team member. We will spend more time on this phase than any other part of the course, because it is so vital to the survival of the team. The first 10 to 15 seconds of the contact will have a tremendous impact on the final outcome of the firefight. Every member of the team must know exactly what to do instantly and execute his duties immediately and exactly. The only way you achieve that level of performance is practice, practice, practice, and when you have it down to absolute perfection, practice some more!

All the FOB’s have firing ranges and training where teams can do live fire IA Drills. Again it is essential that every member of the team participate in the training and is totally proficient in the drills.

In addition to contact drills, there will be drills for actions on the insertion LZ and the extraction LZ. The same as the contact IA Drills, every team member must know his responsibilities both going in and coming out.

Coming out of a hot LZ can be a harrowing experience, especially when you have the enemy only a few meters behind you and/or surrounding the LZ. Whether it be the Vietnamese Kingbees or the American Hueys, those crews are fearless and dedicated to getting you out.

Needless to say, when the LZ is full of hostile gunfire, everyone’s nerves are on edge. Again, our operation is unique and when a door gunner sees a guy in a NVA uniform carrying an AK come busting out of the tree line running toward his helicopter, he’s very likely to open up on him. Some of the teams have the point man in NVA uniform and carrying AK’s, and in fact we did have a team member shot by a jumpy door gunner. Fortunately the team member survived and a resourceful 1-0 came up with an effective technique. The team would carry two or three colored bandannas in their pockets, and if the LZ might be hot just before choppers arrived the 1-0 will tell covey “team color is yellow”, and each team member would tie a yellow bandanna around their head or neck. That way, anybody without a yellow bandanna on the LZ is fair game. It’s not a mandatory technique, but it’s something to consider. Two or three bandannas in your pocket don’t weigh much and it works. As the 1-0, it’s your call.

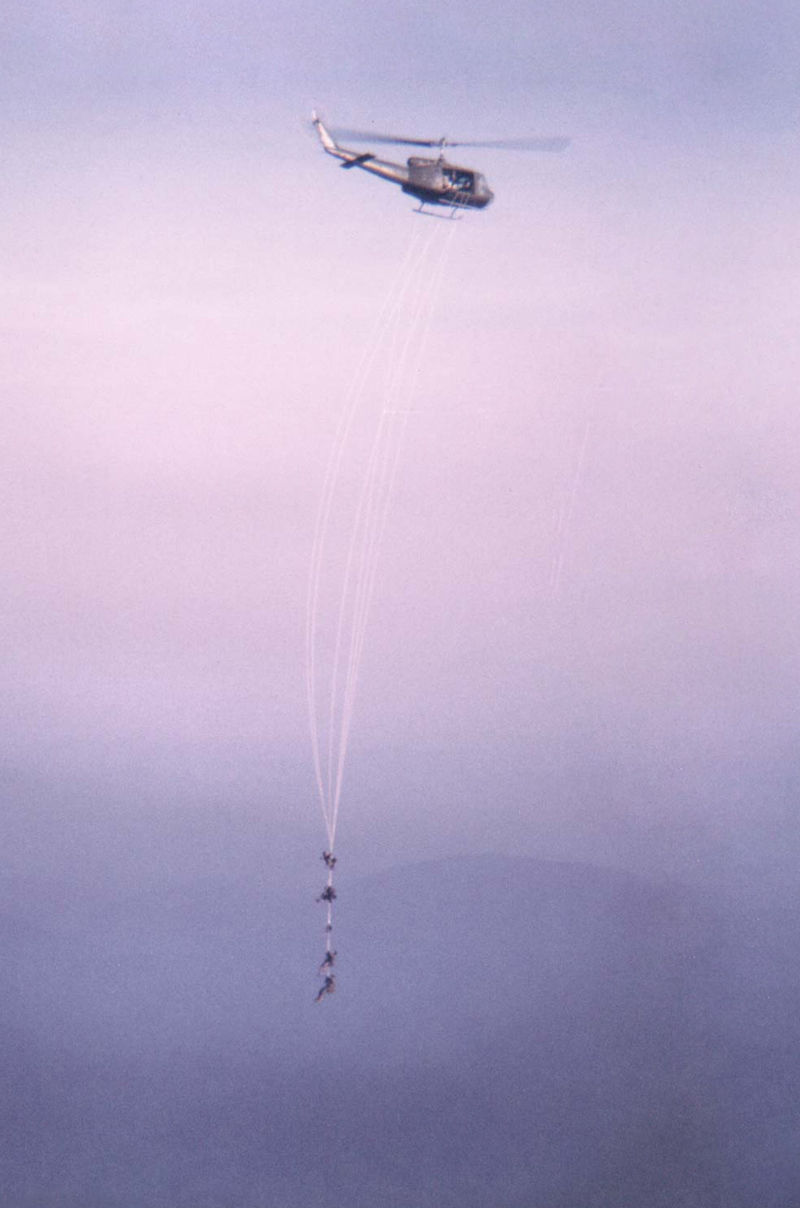

Combat recon team extraction utilizing McGuire rigs. (Photo credit, Bill Quigley)

Another extraction technique that is pretty unique to SOG is coming out on strings, i.e., McGuire rigs or just on the end of a 150 ft. climbing rope with a Swiss seat. During this course, you will ride a McGuire rig and do a string extraction. I had a very personal experience with a McGuire rig extraction and I assure you the time to start learning how to ride a McGuire rig is not when it comes crashing through the trees.

Another area of importance will be directing air strikes. In the Prairie Fire A/O you will have air support from the Air Force with fast movers (jets) and A1-E’s from Thailand. You will communicate with the Covey rider and he and the Covey pilot will communicate with the attack aircraft. The jets will have 20mm cannons, 500 lb. bombs, and napalm canisters.

Unfortunately the jets consume fuel enormously and usually can only stay on station for about 15 minutes. The A1-E’s can stay on station for about an hour, with 50 cal wing guns and 8 250 lb. bombs and 2 napalm canisters. In addition to being able to stay on station, they move slow and can accurately put their ordnance within 50 meters of your position.

Unfortunately in the Daniel Boone A/O you won’t have the luxury of air strikes, you will only have helicopter gunship support. During the course we won’t have jets or A1-E’s, but we will have a two FAC (Forward Air Controller) aircraft, one being the Covey with one of the instructors serving as Covey rider. FAC 1 will fire WP rockets to mark your “target” based on your directions (azimuth and distance) and FAC 2 will roll in and fire HP rockets on the “smoke”.

You will be evaluated and critiqued on your ability to accurately direct the “air strike”. Once you are “on the ground” your team’s survival could very well depend on your ability to accurately direct the air strikes.

Long Thanh didn’t have any assigned air assets, so I had to find some way to acquire the necessary support to be able to do the air strike training.

Topic Five: Physical Conditioning

Last, but not all least, there will be plenty of physical condition training. It will include road marches with 60 lb. rucksacks, running and some variation of the Army Daily Dozen. This is not just something to do to take up time on the training schedule. There will come a time when your survival will depend on you being able to out run, out walk, or out endure the enemy chasing you.

___________________________________

That pretty much covered the major training areas we could cover in the time allotted. There were two areas we were not going to spend much time on: (1) was map reading and land navigation; and (2) was artillery and mortar adjustment. Every student was a graduate of the SF Q-Course which had extensive instruction on map reading and land navigation. If you are not proficient now, we don’t have time to teach you. You will be evaluated and critiqued during our exercises and training here, but that is a skill you should have by now. Also, calling for and adjusting artillery and mortar fire is another skill you should already have. In our area of operations, artillery and mortar support is all but non-existent, therefore we are not going to spend time on it.

With the basic subject matter pretty well set, we started working on how we were going to get it done. All of us that were there as the cadre had gotten our training from our team leaders. Also one of the major learning methods was when a 1-0 came back from a mission and had encountered something new, everyone would gather around in the club as he would recount what the enemy had thrown at him and how he had been able to counter it. It would be an open discussion with questions and suggestions (what if’s) from the other 1-0’s to begin the formulation of possible responses and/or prevention measures for the enemy’s new tactics and techniques. It was informal but very intense and effective. It was a system we all knew and were comfortable with.

I decided we would use somewhat of a modified version of that system. The classes would be small, between 20 to 24 students. There would be a primary instructor assigned for that segment and the other instructors that were not otherwise engaged in preparation or support would be in the classroom. The primary instructor would start with a presentation on the subject matter, then it would be an open question and answer session with all the other 1-0’s and/or 1-1’s providing insights and answers to the “what if” situations from the students. We all felt this would be close to the “around the table in the club” sessions and the students will feel they are getting the real information “straight from the horses’ mouth.”

In addition to the classroom sessions, there would be a significant amount of field work, i.e., IA Drills, both dry run and live fire, range firing, demolitions training, air strikes, etc.

As mentioned earlier, Long Thanh was a large camp with extensive training areas and facilities to support the many projects within the camp. It had a very substantial firing range with sufficient area for live fire IA Drills as well as a demo range. One of the major cover stories for the camp was conducting a Vietnamese Jump School, so it had an area for airborne training and a drop zone. (In fact the Vietnamese cadre did conduct 2 or 3 airborne cycles per year just to keep up the cover story). It had very adequate classrooms and a training aid production shop. All in all, it was a very adequate location for the 1-0 School. We, the cadre, spent the next two weeks preparing lesson outlines, scheduling ranges and training areas, fine tuning the training schedule and getting acclimated to the camp and camp personnel.

As I outlined earlier, Long Thanh was an OP 34 camp and we were all OP 35 people. Because of the strict compartmentalization within SOG very few knew what the other sections did, so at first it was somewhat of an uneasy relationship. We were all Special Forces and as the instructors arrived, some of them knew some of the camp personnel from prior assignments in other Groups. During the first couple of weeks over a few drinks in the club we all began to feel more comfortable with each other. By the time the first group of students arrived, we had established a good working relationship between the camp and the 1-0 School.

The students arrived on a Sunday afternoon. Once we got them settled into the barracks, we gathered them in a class room and gave them the orientation briefing. We explained this camp had several other missions in addition to supporting this school. Just like our missions, theirs are classified as well, so respect the restricted areas and don’t be asking questions regarding the other projects.

We explained this is going to be different from any school they have been to before. This is not an academic exercise; there will be no written exams. Everything is going to be hands-on. Whether you pass or fail will depend on your team instructor/team leader. For the “final exam” he will take you on a real target. Only if he feels you are a competent team member will you successfully complete this course. You will not receive a Certificate. This is not a sanctioned school, it will not be recorded in your personnel file. You will get a Zippo lighter with the SOG Crest, a firm hand shake and a ride to the airfield to catch the next Blackbird back to your FOB. The training schedule runs 7 days a week. There are no “off days”. We only have 3 weeks to teach you a tremendous amount of information. Our goal is to teach you the essential survival skills for what will likely be the most difficult assignment of your career. We will start early with PT and some days will extend into the night.

After a question and answer period, we took them on an orientation tour of the camp pointing out the mess hall, dispensary, club, showers, etc. We finished with rules and etiquette of the club and cautioned not to stay too late — we will be starting early tomorrow.

About the Author:

Travis Mills enlisted in the U.S. Army, June 1966 — Basic and Infantry AIT. Following AIT Pvt. Travis was assigned as cadre in a basic training unit where he was promoted to Corporal. He then attended OCS at Fort Benning, GA, graduating as the Honor and Distinguished Graduate. 2nd Lt Mills next attended Jump School and was then assigned to the 7th SFGA at Fort Bragg, NC, where he completed the Special Forces Officers Course and then served as XO on an A-Team.

Receiving orders transferring him to Vietnam where he arrived in May 1968 and was assigned to 5th SFGA. Then 1st Lt Mills was assigned to MACV-SOG Command and Control in Da Nang, then to FOB 4 at Marble Mountain. Initially assigned as a platoon leader of the Hatchet Force, he was later transferred to the Recon Company and served as 1-1, 1-0 on RT Python and RT Coral.

Following discharge from the hospital for his serious wounds on August 23, 1st LT Mills was assigned TDY to B-53 in Long Thanh to start the MACV-SOG One Zero (1-0) School. In June 1969 LT Mills was promoted to Captain. In December 1969 he was reassigned to 1st SFGA in Okinawa where he spent thirty months as an A-Team Commander on various missions to Korea, Taiwan, the Philippine Islands and Japan. While stationed in Okinawa he graduated from Jump Master School.

In July 1972 Captain Mills was assigned to Fort Hood, Texas. With the down sizing of the Army after the withdrawal from Vietnam Captain Mills was released from active duty and honorably discharged on November 1973.

Awards and Decorations

Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart, CIB, Presidential Unit Citation (MACV-SOG), Vietnam, Chinese and Korean Jump Wings and the “usual” decorations and badges.

How does SOG differ from the LRR (lerp) teams of the mid 60s?

Damn good stuff!…Nothing but cold hard reality!

Damn good stuff!… Without doubt your no nonsense brass tacks training criteria saved countless American and friendly indig lives while sending a steady flow of the enemy to their maker.