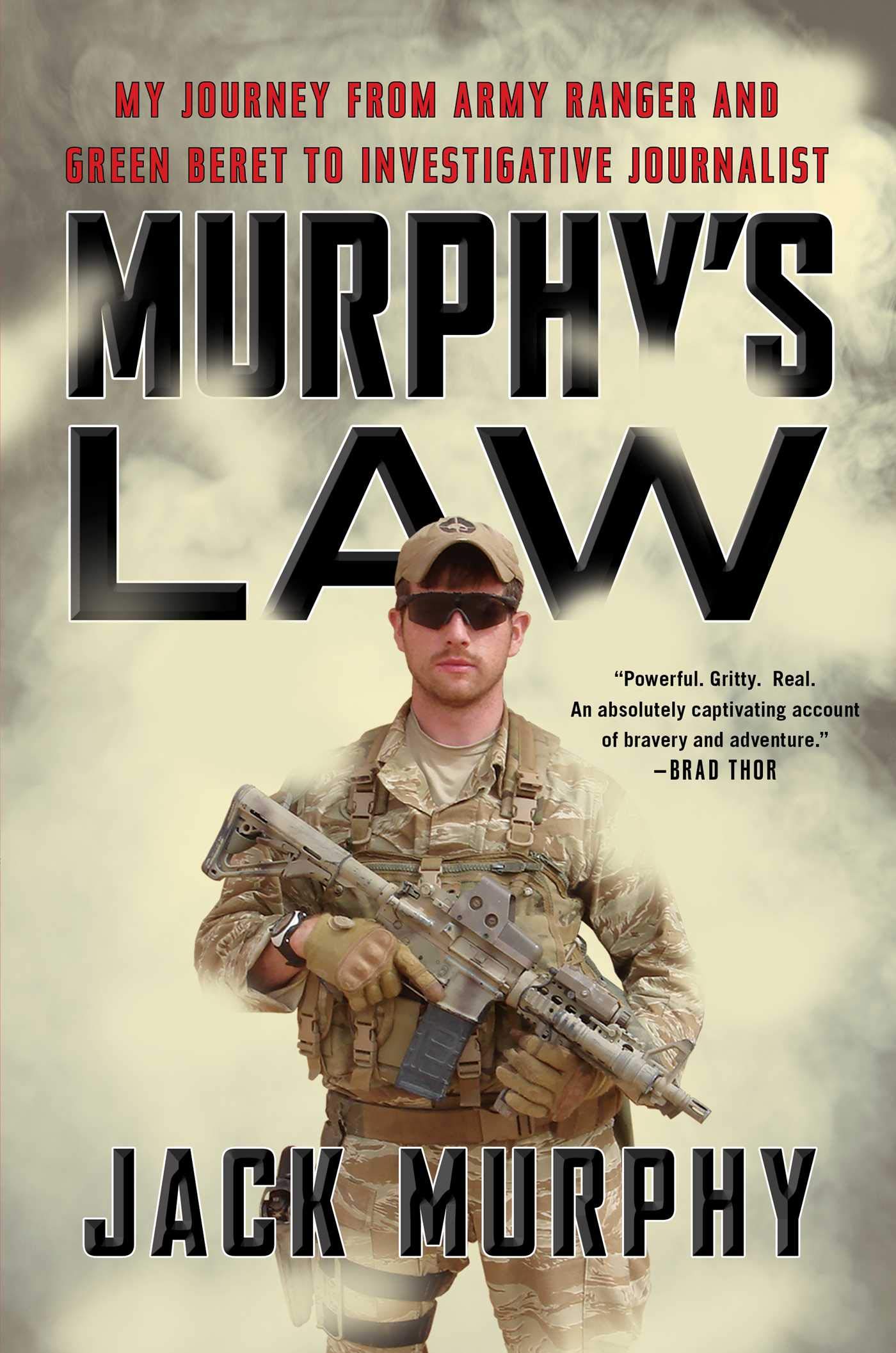

An Excerpt From—Murphy’s Law:

My Journey from Army Green Beret to Investigative Journalist

By Jack Murphy

Excerpted from Murphy’s Law: My Journey from Army Ranger and Green Beret to Investigative Journalist, published by Threshold Editions, (April 23, 2019), pages 109–122

I arrived at 5th Special Forces group in 2007. I got assigned to 4th Battalion. After 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld had issued a directive that Special Forces was to rapidly expand. The Pentagon, Special Forces Command, and General Parker at the Special Warfare complied with this policy decision but in the process ended up violating what are known as the Special Operations Forces (SOF) Truths, which are as follows:

- Humans are more important than Hardware.

- Quality is better than Quantity.

- Special Operations Forces cannot be mass produced.

- Competent Special Operations Forces cannot be created after emergencies occur.

- Most Special Operations require non-SOF assistance.

As I had begun to see in the Q-Course, then more so as a member of Special Forces, we were violating all of these so-called truths and continue to do so to this day. We mass produce young soldiers for these units while turning a blind eye to the massive retention issues. No one wants to ask why hardly anyone stays in these units.

I tried to get out of the 4th Battalion assignment because it was a brand-new battalion that we had to stand up from scratch, so we would not be deploying any time soon. I was unsuccessful in this endeavor. When I showed up, the Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) teams were filling up with sergeants, but we had no equipment and few officers. We didn’t have team rooms and hung out in 5th Group’s isolation facility. Our first battalion commander got into trouble and was allowed to quietly retire. He allegedly had classified information on his personal computer and his wife dimed him out to Army investigators during the course of a messy divorce. These types of incidents are rarely reported in the press but they happen just about every day.

I had expected to be the youngest, most inexperienced Green Beret on an ODA filled with salty old sergeants. It turned out that I was one of the more experienced guys and was immediately made the senior weapons sergeant on my team. It was kind of a frustrating mess. In time, weapons and gear floated in, and we began training on Fort Campbell. We all tried to make the best of it.

One advantage of standing up a new battalion is that there is no shortage of training to attend. Personally, I enjoyed combat training and liked learning new things and mastering new skills. It was head and shoulders above garrison life, which was mostly about getting down on your kneepads for the officer class and endless online training modules that are done simply to “check the block” on some spreadsheet that shows you are “T” for trained in some useless administrative task.

ODA 5414 team picture in Tal Afar Iraq, 2009 (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

I went to the Military Free Fall course, which, of all the classes I attended in the army, was the most fun. We also got to do off-road driving at AM General, urban driving at Gryphon Group, which is a training program run by a private company in Florida, live-tissue medical training, shooting courses at Mid-South, which is a privately run marksmanship school, the Glock armorers’ course, the SOF armorers’ course, and more.

More than once during this period of time, I packed two bags, taking one to a course and leaving the other at my apartment in Clarksville. I would return home from one course, drop my bag, pick up the one I had left behind, and go right back out the door to the next course.

It wasn’t all fun and games, though. At the SOP armorers’ course in Indiana I went out for dinner with my junior weapons sergeant. I probably had seven glasses of Johnnie Walker Black Label; I don’t remember what my junior was drinking. A third student drove us back to our hotel, and my junior decided that it was time for me to go to bed. I said, “Yeah, sure, but I need to brush my teeth.” I got up and headed to the sink. My junior was not having it; he had decided that I needed to go to bed right goddamn now! He tackled me from behind, and we both went flying into a corner, wrecking a lamp and a trash can. As we fought each other, he decided to bite down on my shoulder with his teeth. “Ow, you goddamn asshole, what the fuck is wrong with you!” Convinced that I would now go to bed, my junior finally knocked it off and went to his room.

Normally, I would have just shrugged something like that off, but get this: We were done with the course and heading back to Clarksville the next day. My girlfriend was flying in to meet me, and guess who now had a huge bite mark on his shoulder? You could see individual teeth marks, for Christ’s sake! Yeah, good fucking luck explaining that to your girlfriend: Oh, yeah, honey, that was my battle buddy. He had a few too many, tackled me into the corner of a hotel room, and bit me. I wouldn’t believe that shit if someone told me. But by the grace of God, she never noticed the bite mark. This is where being Irish pays off, as it must have blended in with the freckles on my shoulder.

Back at the home station, we got team rooms, and our gear was filtering in, but most important, we got a deployment schedule. We had some great guys on my ODA, but overall, I found 5th Group to be insanely bureaucratic and very conventional in how they did things. The nickname “5th Ranger Battalion” often gets applied to 5th Special Forces Group. It was a sharp contrast from Ranger Battalion, where we had our own compound and did things our own way; 5th Group seemed shackled by Mother Army. Officers and senior NCOs treated it like a conventional unit despite its being organized and equipped for unconventional warfare. This resulted in suboptimal performance, to say the least.

We were also bombarded with asinine online training modules. The modern army has gone completely corporate. Strong leadership has been replaced by statistical analysis and measuring metrics. The sole purpose of soldiers is to provide warm bodies so that officers can claim they command a unit. Their task from day to day is not preparing for war but filling trackers. Soldiers need to be “green” on their tasks at all times. That isn’t to say that they need to be technically and tactically proficient; no one cares about that, no one measures that. What is most important is that they have an up-to-date medical profile, their sexual harassment training, their quarterly information security training, their online SERE refresher (where they run around in a bullshit video game, rubbing sticks together to make a fire), and a hundred other completely worthless requirements that do nothing other than help some careerist officer cover his ass. It is a soulless, counterproductive, and cynical approach to leadership that places “qualifications” ahead of readiness.

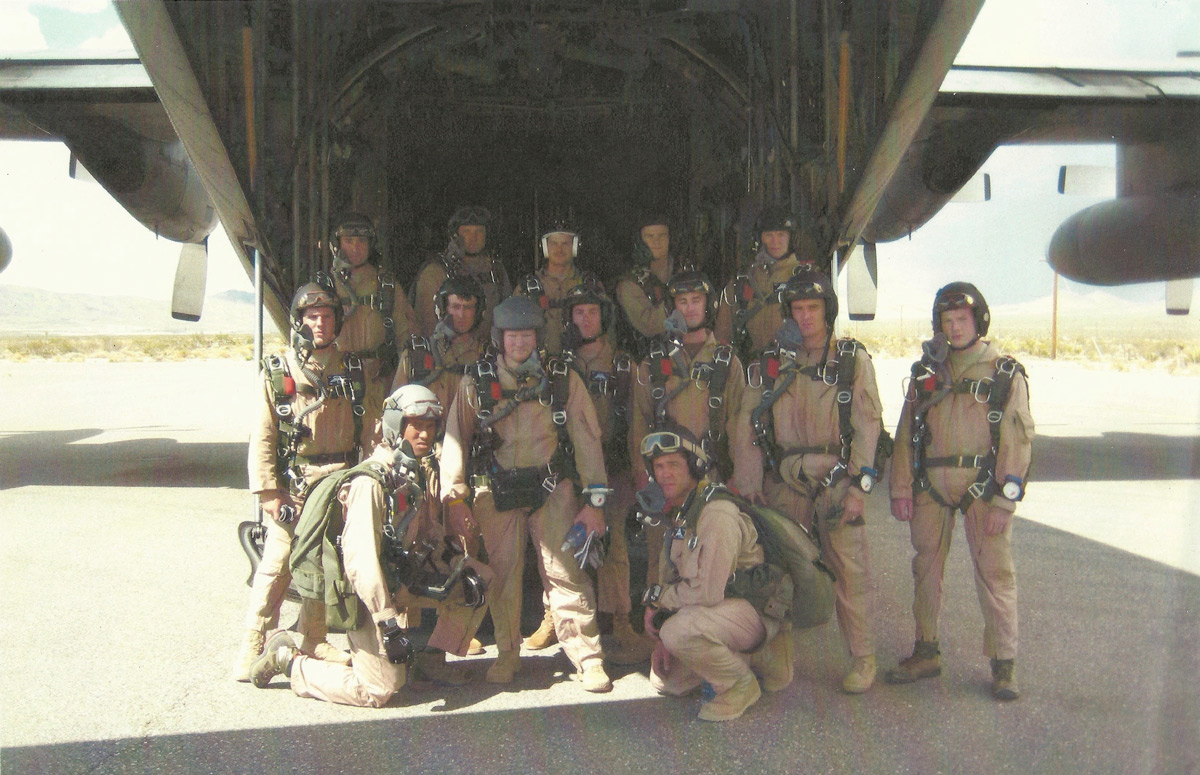

The ODA and a few attachments doing a Military Free Fall train up prior to our deployment to Iraq. (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

Dr. Leonard Wong at the U.S. Army War College did a study which found that our soldiers are tasked with so much mandatory training army-wide that leaders don’t have any time to train soldiers on their actual jobs. Furthermore, the army tells us to conduct more mandatory training than there are training days on the calendar. But it gets better, because officers are reporting to higher-ups that yes, they are in fact conducting all mandatory training to standard. This is impossible. Every officer in the U.S. Army is sending up false reports. What the army has done is conditioned entire generations of soldiers to feel that it is okay to compromise their integrity, not once but twice. The first compromise is the criminally negligent act of not preparing their men for combat. The second is lying about it.

Let me explain how this works on a team level. Your team sergeant comes into the team room and lectures you all on how you need to have your trackers up to date and be in the green on all assigned admin tasks. He is saying this because his bosses are holding his feet to the fire. So instead of training, troops are busy sitting behind a computer, mindlessly clicking through an online test module from the bullshit army safety center. No one gives a fuck, and no one gives a fuck that no one gives a fuck. It is a military culture of not taking pride in your work. You finish your online training, print out a certificate, hand it to your chain of command, they update the tracker, and your team is “trained” up on the whiteboard.

I understand that running a team is about more than what you see in the recruitment commercials. There are logistics and administrative tasks that need to be handled. Guys need to go to the dentist, soldiers need to understand the Geneva Convention, but at some point, this shit has gotten completely out of control. I really can’t begin to explain how dehumanizing and demoralizing the cynical corporate culture is. More so when, on a daily basis, you hear about our troops being killed fighting our war overseas. Some of us joined the army and took this war seriously. We wanted to win. I never gave a fuck about having a “career” and would have been happy to just be a senior weapons sergeant forever. I mean, when you look at your senior NCOs and see that they are emasculated secretaries for some colonel, you have to ask why the hell would you want to get promoted in the first place?

As an ODA, we were now going into our pre-deployment workup in 2007. We did a HALO/HAHO train-up in Las Vegas and then a few weeks of pre-mission training (PMT) at Fort Knox. HALO and HAHO are both forms of military free-fall parachuting. High-altitude Low-opening is when you jump from an airplane at high altitude, up to thirty thousand feet, and deploy your parachute around four thousand feet. In a high-altitude high-opening jump, you deploy your parachute immediately after exiting the aircraft and glide under canopy for long distances, perhaps even across an international border. These are clandestine infiltration techniques designed to insert Special Forces teams into denied areas.

The parachute riggers were good to go, but most of the group support personnel were about as lethargic as you could possibly imagine, supporting no one but themselves. They seemed to expect a bribe of a bottle of whiskey just to get them out of their chairs. Talk about frustrating. At the end of the day, it is the ODA itself that pulls together, works as a team, and ultimately bends if not breaks the rules in order to complete their mission, out of necessity.

A new team sergeant who came to our team before our HALO train-up asked that I refer to him as Michael Bluth, the name of the main character in Arrested Development, which he got me watching on DVD while we were in Iraq. He told us that no one can be trusted outside our team room doors. He wasn’t mistaken.

Finally, our deployment date rolled around. Guess where we were heading? My old stomping grounds: Tal Afar.

ODA 5414 deployed to Iraq in the winter of 2009. It was our first operational deployment. We hit the ground at FOB Sykes and conducted a relief in place with the ODA that was on the way out. The outgoing 18B (weapons sergeant) walked me through the situation, taking me to the arms room, the conex containers full of ammo, and then introduced me to the Tal Afar SWAT team.

The author, manning the .50 Ma Deuce as we head out on a patrol in N. Iraq (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

The Iraqi SWAT team members were living in some old Saddam-era bunkers on the FOB, alternating between two shifts, each consisting of a platoon-sized element. One platoon would be at home while the other was in the bunkers, training and waiting for missions. These guys had been selected and trained by U.S. Special Forces, and frankly, I was just the latest cock on the block to take them under my wing. Inside the bunker, we met the SWAT team leaders, smoked cigarettes, and played get to-know-you. Iraqis will ask you what your birthday is and be impressed when you tell them the month and day. They usually only know what year they were born, such are the medical records in that part of the world. I met Salem, the SWAT commander, and his right-hand men, Qasim, Faisal, and Shahab. They turned out to be great partners and friends. Unfortunately, the other platoon turned out to be subpar.

My ODA’s compound consisted of a series of CHUs, or containerized housing units, set on cinder blocks in long rows; two CHUs could be welded together, and this was the case for our arms room, our loadout room, the operations center (OPCEN), and a couple other structures. The mechanics had a large tent where they could work on vehicles, and we had a small fleet of Humvees and MRAPs and some civilian cars and trucks for driving around the base and to the chow hall. We also had a fire pit, around which many a party was had.

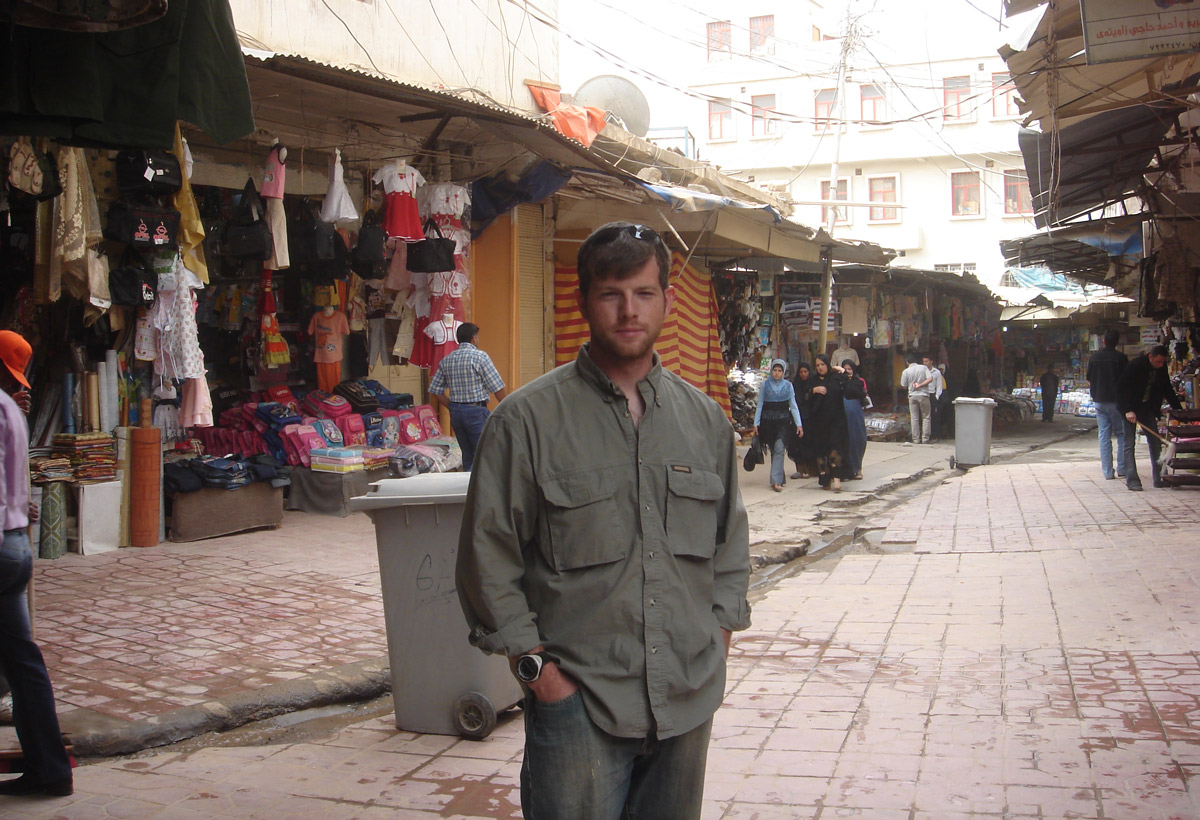

On our initial ride through Tal Afar that deployment, I recognized many sights, even though it was my first time being there in daylight. The city was transformed. Four years prior, you could not set foot in Tal Afar without getting into a firefight; now we could walk around the market without body armor and just a pistol on our hip. Finally, a positive counterinsurgency story!

Sure, five years later, the American presence would no longer exist, and the entire city would be taken over by ISIS and its population enslaved by jihadists, but that’s another story. Let’s bask in our successes for a few moments, shall we?

While we drove down the streets on that initial ride-along, I was up in the gun turret behind the .50-cal. I silently observed several collapsed houses where the roof and individual floors had pancaked on top of one another, concrete left crumbling under the hot Iraqi sun. These were the houses we had called in AC-130 strikes on four years ago. There was no reconstruction for Iraq, and this became even more evident when we began making trips in Mosul.

The enemy situation had changed drastically. By this time AQI had been brought to their knees. The special operations task force had pushed their shit in, but that’s something you won’t hear much about in the press. The task force I’d been a part of had in fact helped quell the insurgency, and now there was a great opportunity to consolidate gains, build infrastructure, and enable good governance in Iraq. Sadly, none of this was to happen. Before we left, our commanders had told us that our mission success would be based on how few combat operations we’d done, because now we were to transition authority over to the Iraqis, especially with a new Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) being signed. This opinion changed when we hit the ground, and our chain of command began pushing us to submit CONOPs (concept of the operations) plans for combat missions.

Everyone knew that Obama would have us withdraw from the country. In the end, the administration uprooted the entire infrastructure that had been built in-country, including vast intelligence networks, something that had never been done before. I and many others quickly deduced that this was a bad idea. Yes, the Iraqis needed to step up, and none of us wanted to be their colonial masters, but the reality is that the country wasn’t ready. The government did not function and was rife with corruption. However, orders were orders, and during this time, the army put in a diligent effort to make it look like things were good in Iraq.

Doing some recon for a training exercise near our FOB. (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

Commanders on the ground were being actively encouraged to send up false reports to higher, making the situation on the ground look much rosier than it was. A policy decision had been made from up high, and now the foot soldiers in this war had to make reality fit into the bubble that our politicians had created back stateside.

When I mentioned to my team leader that if we left, Iraq would become a terrorist state like Afghanistan in 2001, my captain said, “Well, that is just stating the obvious.”

We all knew.

While AQI had been all but put out of business, another enemy was beginning to rear its head. They called themselves the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) and were based out of Syria, where we couldn’t touch them. The group consisted of former Baath Party members like Al-Douri and Saddam Hussein’s daughter, visions of the old regime dancing in front of their eyes like sugarplum fairies. Their primary tactic was to attack only coalition forces in Iraq, rather than alienating the locals, like AQI, which was basically a glorified death cult. The enemy was learning.

So, we came up with a training schedule for the SWAT team, getting them out on the range shooting, running through the shoot house, doing medical classes, and all of that good army training, while we put together targeting packets. Soon the intel that the previous team had developed on a terrorist in Mosul named Abu Gaini began to come together.

If you want to catch a terrorist, you have to locate him first, and the one place where you know he will be is at his own wedding.

By 2009, insurgents and terrorists in Iraq had gotten fairly wily. The enemy had learned from their engagements with U.S. Special Operations Forces, and they were taking increasingly sophisticated measures to try to trip us up and avoid our raids. So, when we found out that a big-name terrorist was getting married, and where the marriage would be held, a lot of uncertainty was taken out of the equation. This moron had to be at his own damn wedding.

Once we had solid intel on the date and location of the wedding, we rolled into Mosul that afternoon in our Humvees, heading toward the target house. One difference between my time with the Ranger regiment and my new job was that, as a Special Forces team, we were always partnered with our Iraqi counterparts, in this case a SWAT team from Tal Afar. With a platoon-sized element of Iraqis, our ODA snaked the vehicles through the flooded back alleys of Mosul.

The city had taken a beating since I was there four years before. Mosul had looked like Beirut back in the eighties, with a number of collapsed buildings and structures covered in bullet pockmarks. Mosul had always been one of the most violent cities in Iraq, and now the enemy was building bigger IEDs to defeat the armor packages that coalition forces had put on vehicles to protect us from the previous IEDs. Like I said, the enemy was learning and adapting.

We navigated our way through the labyrinth of back roads on the north side of the city. The streets were partially flooded with brown water; rocks and pebbles gathered in clusters on the roadsides. Kids looked at us with a mix of curiosity and shock as we slow-rolled past them, searching for the target building.

As silently as possible, we pulled up in front of the objective building and unassed the vehicles. We quietly opened doors and crept down the street in broad daylight.

I was an assault team leader, taking four Iraqi SWAT troops through the front door. We quickly pushed through the open front gate into the inner courtyard. It was all over in a flash, fairly anticlimatic, which is the way it should be. If the enemy has time to react to your raid, then you’ve lost the element of surprise and, with it, the advantage. Special Forces soldiers like to engage the enemy at a place and time of their choosing, rather than letting the enemy dictate the terms of the fight.

We flooded the compound with assaulters, clearing rooms, sending men scurrying up ladders to the roof, locking down every doorway and potential avenue of escape. The fighting-age men had guns trained on them and were flex-cuffed in short order.

The two 18B (weapons sergeants) including myself and my junior bravo standing with Iraqi SWAT partners at the castle in the middle of Tal Afar. The castle was later dismantled by ISIS as a part of their ethnic cleansing of the area. (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

Abu Gaini, the terrorist we were after, was in the courtyard with the other men. The wedding ceremony was complete, and at this point the men would have begun drinking. The dowry (a lethargic goat that sat panting in the courtyard for the duration of our stay on the objective) would have been killed and a meal cooked. Instead, Abu Gaini was put on the ground; a Glock 19 pistol was found tucked into the waistband of his suit.

In the back room, the women were holding court separately. A lone Iraqi SWAT team member stood sentry in the doorway but wasn’t interacting with the women in any way. The SWAT guys were scared to death of women, it seemed, but I suppose that was better than the opposite — we never had to deal with them acting inappropriately toward women on target.

The bride broke out in tears as we secured the home, and the Iraqi women began screaming at us. As we soon found out, the bride was only sixteen years old. We left the women alone and didn’t put our hands on any of them — we prefer not to, and it is additionally offensive to the culture, so we avoid it.

But it gets better. We’d crashed the wedding at the eleventh hour. Had we delayed any longer — had we gotten lost down one of the side streets, for example — the terrorist would have consummated the marriage. We crashed the wedding just in time to save a teenage girl’s virginity from this terrorist asshole. This was how our ODA got the name “The Wedding Crashers.”

While one of our ODA members questioned the terrorist, the bad guy said to him through an interpreter that if we knew who he was, then we knew what he had done — killing people and setting off IEDs for cash and for his terrorist cause. “Just put a bullet in my head now,” he begged. No dice. Under the recently signed Status of Forces Agreement, he would be sent directly to an Iraqi prison. After flex-cuffing the terrorist, we decided to haul in his old man as well. His father was involved in his son’s criminal enterprise on some level, though we weren’t sure exactly how.

I grabbed the father under his arm, helped him up, and led him through the gate and out into the street where our vehicles were waiting. Our source sat in one of the Humvees, wearing a scarf around his face. When I led the old man in front of the source, he silently nodded. This was the guy. The old man just laughed; he looked back at me and chuckled. I stood him next to a wall while we prepared to load all of the detainees on our vehicles. Abu Gaini’s father was totally nonchalant about the whole affair, as if it were all a joke. I couldn’t figure him out.

Back at our base, FOB Sykes in Tal Afar, I sat down in the bunker where our ISWAT team was quartered. We were just sitting around, smoking cigarettes and generally shooting the shit. One of them mentioned to me that the “old man,” the terrorist’s father, had killed his cousin, who had been a police officer. This piqued my interest, and I asked him what he was talking about.

Back in 2005, Tal Afar had been a straight-up terrorist sanctuary. Recall my previous experiences in Tal Afar, when I was in Ranger Battalion. Back during the bad old days of Tal Afar, which in 2009 was fairly peaceful, the father had been issuing fatwahs on people and was known as an accomplished insurgent sniper. One guy told me that the old man could take the cherry off of a cigarette from a thousand meters away. Surely an exaggeration, but it showed how afraid of him they were. Abu Gaini’s father had murdered a lot of people, including policemen, and the citizens of Tal Afar had no sympathy for this guy.

I walked into the back of the bunker where the old man was sitting on the floor under guard by the Iraqi SWAT team members. He was looking around and smiling at everyone with not a care in the world. I asked him some questions through our interpreter about his past activities. I told him that I had heard he was a pretty good sniper. He just laughed and threw up his handcuffed hands. “No, no, mister, you got it all wrong.” He was like a serial killer. A psychopath.

Walking around Dohuk, Kurdistan in civilians. (Photo courtesy Jack Murphy)

We used to visit the prison in Tal Afar every so often to see what was up. The terrorist we’d captured in Mosul was always there, even months later, still wearing his wedding suit. The Iraqi warden kept him handcuffed to the bars of his cell in the standing position so he could never sit down. Don’t blame Americans for this sort of mistreatment — we were completely hands-off due to that Status of Forces Agreement I mentioned previously. We would have imprisoned him humanely, but what the Iraqis did to each other was their business. As American soldiers, we could express disagreement to our host nation counterparts, but we had no power to do anything about it.

Sadly, the prison warden was himself killed by an Al-Qaeda suicide bomber who showed up at his front door one night during this same six-month deployment. Took the warden’s entire family in the blast, everyone except a second cousin. The cousin felt that the attack had been directed against his family by Shias because they were Sunni. To get revenge, he went into the market with an AK-47 and started gunning down Shias in cold blood until the Iraqi military showed up and wasted him.

This is the insanity that is Iraq.

Now, how about the terrorist’s father, the old man? He had murdered too many innocent people in Tal Afar to be allowed to live. I never saw him again after we dropped him off at the prison that first time. I later heard through the grapevine that the Iraqis disappeared him out in the desert somewhere.

In 2009, the situation on the ground in Iraq was getting increasingly convoluted. The amount of bureaucracy you had to go through to get anything done was off the charts. Giving the Iraqis medical training in a classroom on our base required a memo from a colonel; the conventional American troops did not like interacting with my ISWAT team; every colonel in the country had a big idea about how they were going to win the war. One unfortunate statement from our high headquarters was that we needed to get them all the information they needed to win the war. How the hell was a Special Forces staff office going to win a war? We needed their support, but from their perspective, we (the maneuver element) had to support them (the staff element) in their effort to achieve total victory in Iraq. Man, this shit was getting weird.

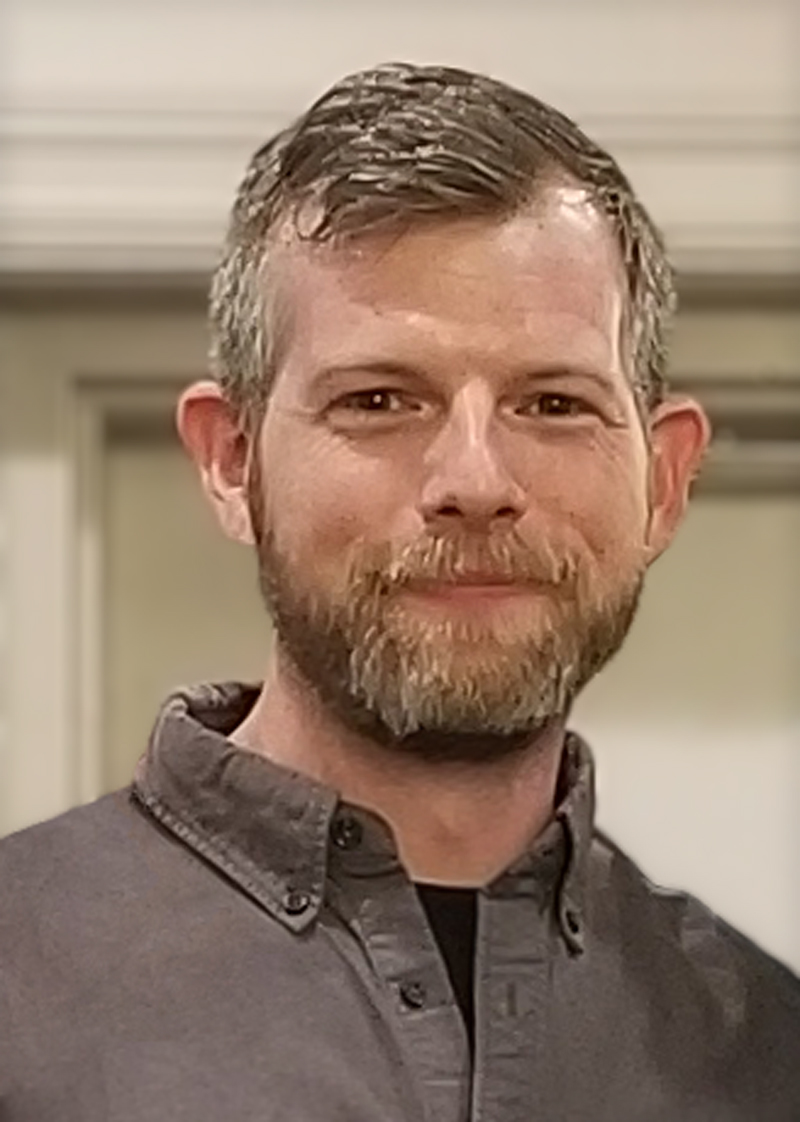

Jack-Murphy-800px

About the Author:

Jack Murphy is a Army Special Operations veteran who served as a Sniper and Team Leader in 3rd Ranger Battalion and as a Senior Weapons Sergeant on a Military Free Fall team in 5th Special Forces Group.

Murphy is the New York Times Bestselling author of Reflexive Fire, Target Deck, and Direct Action. He also co-authored the non-fiction work, Benghazi: The Definitive Report which exploded the true story behind what really happened when the US consulate in Libya came under attack. His memoir Murphy’s Law was published in 2019.

Having left the military in 2010 after serving three combat deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq, he graduated with a BA in political science from Columbia University in 2014. He has worked as an investigative journalist ever since.

Murphy has reported on the ground from conflicts around the world getting smuggled into Syria with Kurdish guerrillas early on during the civil war, embedding with the Peshmerga during combat against ISIS in Iraq, and traveled from Manila to Tawi Tawi interviewing members of Philippine Special Operations Forces. He reports extensively on clandestine and covert operations.

He has made numerous television appearances on national news outlets as a subject matter expert. His work has appeared on Connecting Vets, Stars and Stripes, and Yahoo News.

He is currently a co-host on The Team House podcast on YouTube. The podcast is also available in audio on major podcast resources, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, etc.

Twitter: @JackMurphyRGR

Instagram: @jackmcmurph

Facebook: JackMurphyAuthor

instagram.com/the.team.house

facebook.com/TheTeamHouseLivestream

Leave A Comment