Edmunds & Stonesifer

The GWOT’s 1st Sacrifices

SPC Jonn J. Edmunds, 19 October 2001, Pakistan, Ranger

SPC Kristofor T. Stonesifer, 19 October 2001, Pakistan, Ranger

By Colonel Nils C. ‘Chris’ Sorenson

United States Army Retired

INTRODUCTION

On October 19, 2001, United States Army Rangers, Specialists Jonn Joseph Edmunds, and Kristofor Tif Stonesifer, became the first two combat casualties of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT). They tragically died on a remote airfield in Pakistan, directly supporting America’s initial ground combat operation into Afghanistan following 9/11. Their ultimate sacrifice would not be the last in what has become an endless effort to prevent another attack on the United States.

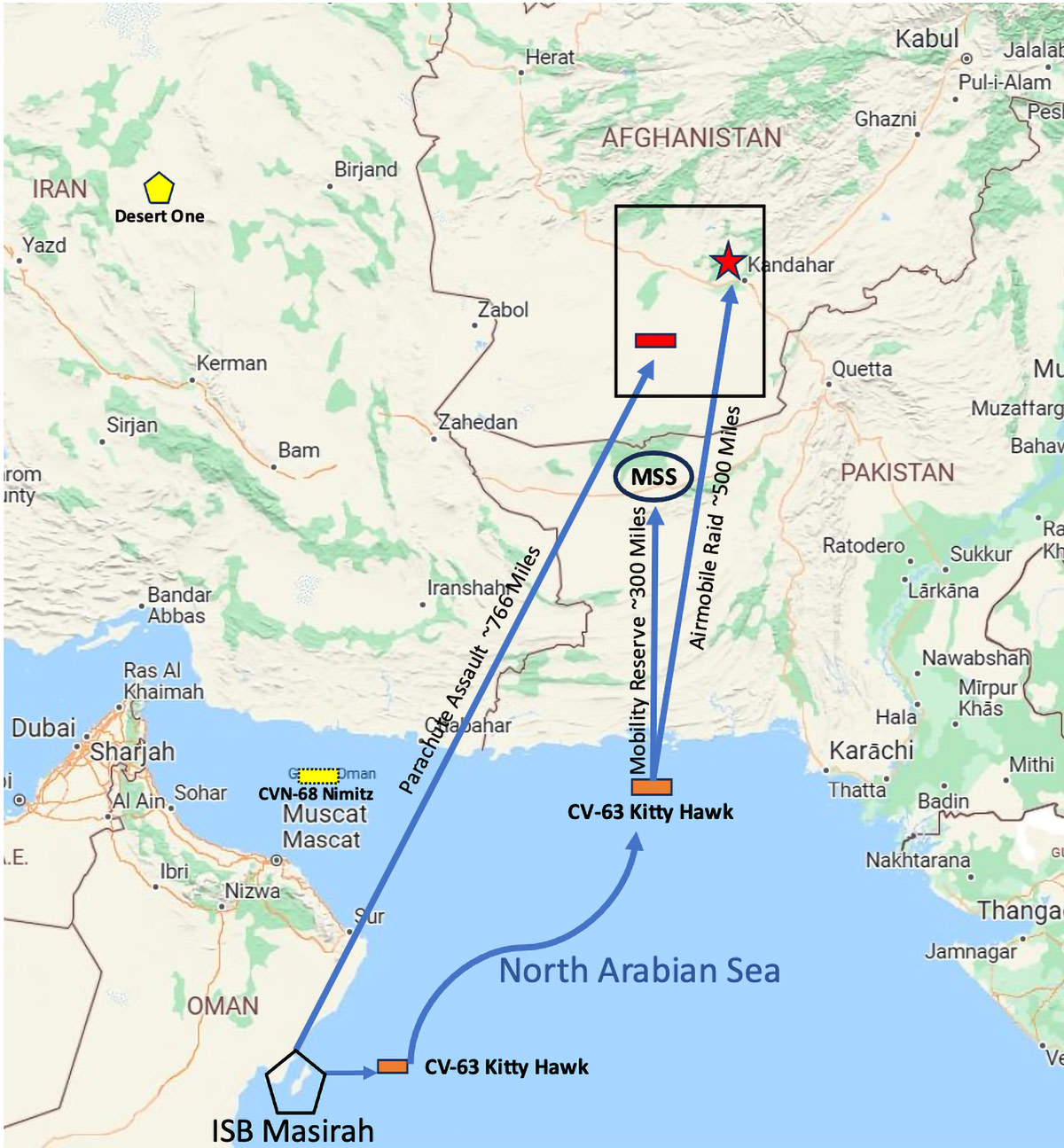

Edmunds and Stonesifer were killed in a rollover crash of their MH-60 Blackhawk helicopter as it was landing at a remote mission support site (MSS) near Dalbandin in southern Pakistan. Their duty that night was to serve as an airmobile reserve for America’s first boots-on-the-ground direct action in Afghanistan. This Presidentially-directed effort required a daring airborne assault to seize a remote airfield as part of a high-risk strategic raid directly into the Taliban’s spiritual center of gravity in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

These actions would not be without precedent; as Edmunds, Stonesifer, and the entire force would closely share the conditions faced by those on Operation Eagle Claw’s Desert One landing site some 21 years before. The joint force would occupy the same intermediate staging base (ISB) on Masirah Island off the east coast of mainland Oman, while the heliborne assets would launch from an aircraft carrier. The targets and support sites would be dark, arid, and dusty—similar circumstances for disaster. However, building on Eagle Claw’s failures, this task force had the benefit of two decades of Congressionally mandated special operations force development. Also during this interim period, the Edmunds family of Cheyenne, Wyoming and the Stonesifer family of Doylestown, Pennsylvania were hard at work building two future special operations Soldiers. Unbeknownst to them at the time, their young sons would grow up to have a critical role in what has since evolved into America’s longest war.

SPC Jonn J. Edmunds

Jonn Edmunds was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado on January 3, 1981; his family moved soon afterwards to Cheyenne, Wyoming. He was a bright student, participating in both the highly competitive American Legion and Future Business Leaders of America programs in high school. In 1999, he graduated from Cheyenne East High School as an honors student and joined the Army at the age of 17; following in the footsteps of his grandfather, who fought in World War II, and his father, who served three tours in Vietnam. Jonn volunteered for the 75th Ranger Regiment and proved himself early on. He worked hard and successfully completed the Army’s prestigious Ranger course. His mom stated that Jonn once proclaimed, “I will be contributing to myself as well as for the defense of this country and for the betterment of the world.”

SPC Kristofor T. Stonesifer

Kristofor ‘Kris’ Stonesifer, the son of a naval flight officer, was born in Key West, Florida on August 20, 1973. He was raised in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. After graduating from Central Bucks West High School, Kris initially attended the University of Delaware. Passionate about the outdoors, Kris took courses at the renowned Tom Brown Tracking School in New Jersey. Then he moved to Montana, putting his skills to work while exploring the state’s parks and wildernesses. He enrolled at the University of Montana and joined the Senior Army ROTC program. His military science professor said Kris was “older and wiser” than his best cadets, confident that Kris would become a decisive, strong leader. However, Kris desired action and left UoM during his junior year in 2000 to join the Army, just before his 27th birthday. Soon afterwards, he too would be selected for the Rangers.

9/11 – A NATION RESPONDS

Both Edmunds and Stonesifer were on duty as part of the Ranger Ready Force when 9/11 occurred. They were in the right place at the right time, and it was finally their opportunity to be a part of something far bigger than themselves. Soon after 9/11, their unit began planning to provide the President with a range of response options. Afterwards, in early October 2001, they deployed to the Middle East and prepared to take part in America’s spearhead assault for the GWOT.

Extreme distances and environmental conditions in the area would soon push man and machine to the limit. As this was the first operation following 9/11, the air bridge to move personnel and material to the region was not yet fully set. Large cargo jets required multiple in-flight refuelings, including a rest and replenishment stop for the crews and passengers at an unprepared air base in Spain where food and bed down capacity were scarce. While the ISB on Masirah Island was well inside U.S. Central Command’s area of responsibility, it was still 750-850 miles away from the actual targets. Modern special operations and strong inter-service cooperation would be critical for success.

USS Kitty Hawk CV-63 with embarked helicopter assault force somewhere in the North Arabian Sea, ca mid-Oct 2001 (Department of Defense photo)

Thus, in early October, the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk CV-63 sortied from its homeport in Japan to serve as an afloat staging base closer to the main target, for special operations helicopters and personnel. Additionally, specialized MC-130 Talon aircraft from the ISB would provide air drop and exfiltration for the supporting target. In-theater close air support and refueling capabilities would struggle to meet operational needs, and there was not a sizeable reserve in case of catastrophic failure. To help mitigate risks, an additional flex force consisting of Rangers and helicopters was designated the ‘mobility reserve’ and included Edmunds and Stonesifer. It had to be positioned within range of the targets without tipping the operation.

The mobility reserve’s MSS would be located south of the Afghanistan border in southwest Pakistan’s Baluchistan province, close to the ingress and egress routes for the heliborne assault force. This remote airstrip lay in an east-west valley surrounded by mountains and the Chagai desert, close to the town of Dalbandin, an ancient trading hub connecting Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. The Pakistanis granted the United States access to this site as a show of support; however, the force was not confident in their true loyalties or intentions.

The force knew very little about this airstrip, or if the locals would welcome Americans occupying it. The mission’s timing would also coincide with the seasonal Wind of 120 Days known for wicked sandstorms across Baluchistan, giving the province the name ‘Powderistan.’ Without eyes on the ground to report conditions, safety of flight information would be a rough guess based off historical data and few black and white satellite images—it would be hairy to say the least; combat procedures would be required.

The 75th Ranger Regiment Distinctive Unit Insignia is worn by all members of the Regiment. This source describes its symbols and historical significance: 22jan_75th_ranger_dui.pdf (arsof-history.org)

SURGING INTO ACTION

Prior to boarding the Kitty Hawk, Edmunds and Stonesifer conducted final mission rehearsals at the ISB with their fellow Rangers, who would soon earn their combat jump wings at a remote airfield in the Helmand desert. Once on the ship, they prepared fervently with the main force that would go ‘downtown.’ They conducted flying rehearsals and became acquainted with their elite Night Stalker crews, who were among the Army’s best aviators. In that time, the force became acutely aware of several serious mission risks: robust estimated enemy armor, artillery, and air defense capabilities; lack of sufficient theater reinforcements; and unknown environmental conditions. The mission also faced the possibility of compromise and ambush, due to the uncertainty as to Pakistan’s reliability and a Department of Defense news release announcing Kitty Hawk’s presence with its embarked helicopters and special forces.

Just prior to sunset on October 19th, 2001, Edmunds and Stonesifer boarded their helicopters and eagerly awaited the signal to launch. Accompanying them on the deck was the larger heliborne assault force that they would be supporting. Meanwhile, several hundred miles southwest at the ISB, their fellow Rangers were rigging for a combat jump in preparation to board their MC-130s for the deep-penetration route to their drop zone. At this point, Edmunds and Stonesifer knew the risks they faced and could not have been better prepared to support the breadth of potential action.

Author’s concept of the operation sketch; locations, distances and routing are approximate. 1980’s Operation Eagle Claw’s Desert One landing zone and the location of the USS Nimitz are shown as reference.

Launching just after sunset, the mobility reserve with Edmunds and Stonesifer rose from the ship’s deck and flew north. By the time they cleared the Pakistan coastline, the night sky dazzled with starlight spanning the mountainous horizon. After nearly three hours of hazardous flying over the water and through the mountains—with an aerial refueling evolution thrown in—the adept pilots found the valley and located the remote airstrip among the arid terrain. As planned, they turned onto final approach south of the Afghanistan border. No trustworthy assets were on the ground to secure the field, so the crew opened the doors and prepared for a combat insertion. On cue, a minute prior to landing, Rangers Edmunds and Stonesifer ‘sat in the door’ and readied their weapons.

Suddenly, just seconds from touchdown, the Blackhawk was enveloped in what could only be described as fine ‘primordial’ dust that obliterated the crew’s vision. They were caught in a vicious brownout never before seen by these well-trained crews, eerily reminiscent of what occurred at Eagle Claw’s Desert One landing strip over two decades prior. Consequently, the aircraft drifted slightly off course and hit a low sand dune with enough force to roll over. Edmunds and Stonesifer were tragically ejected into its path and pinned under its weight. The accident also injured three crew members, who eventually returned to duty. The overall operation successfully completed all assigned missions and achieved its strategic purpose, but at the unfortunate cost of two young Soldiers’ lives.

US Army MH-60 Blackhawk of the type Edmunds and Stonesifer took their final flight on. (DoD Photo by USASOC PAO Walter Sokalski; source: 160th SOAR—MH-60 Black Hawk (americanspecialops.coM) ARSOAC Airframes Page (soc.mil)

HONORING THEIR SACRIFICE

Edmunds’ and Stonesifer’s war ended just as it was beginning. Shortly after the operation, the task force held a memorial on the Kitty Hawk. Stateside, the Army presented each family with their son’s Bronze Star Medal and Purple Heart. Stonesifer was posthumously promoted to Specialist. Large hometown memorial services for both Soldiers were also held. Jonn Edmunds was eventually laid to rest at the Memorial Gardens cemetery in his hometown of Cheyenne, Wyoming (section: Veterans Garden, Lot: 36A, Space 1). Kris Stonesifer was cremated, and his ashes were scattered near Upper Holland Lake in his adopted state of Montana; a headstone was also placed at Arlington National Cemetery (section MH, site 300). Among the services’ attendees were each Soldier’s support network of friends, neighbors, teachers, coaches, and clergy, who had stuck by Edmunds’ and Stonesifer’s sides from the beginning.

Following their battalion’s redeployment in early 2002, the 75th Ranger Regiment held a large service for both Soldiers at Fort Benning, Georgia, engraving their names onto their battalion’s memorial stone. The United States Army Special Operations Command also placed their names on the memorial wall at the command’s headquarters on Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Every Memorial Day, these commands solemnly call the names of Jonn Joseph Edmunds and Kristofor Tif Stonesifer, letting the memories of their sacrifice ring throughout the silence.

Jonn’s marker is at the Cheyenne Memorial Gardens cemetery in Cheyenne, Wyoming; Section: Veterans Garden, Lot: 36A, Space 1; (source: Photos of CPL Jonn Joseph Edmunds — Find a Grave Memorial)

Kris’ marker is in Arlington National Cemetary’s section MH, site 300; source: Kristofor T. Stonesifer — Specialist, United States Army (arlingtoncemetery.net)

IMPACT & LEGACY

What these etchings and utterances do not capture is the strategic significance of their sacrifice in Pakistan that fateful night. They died serving as part of a high-risk combat operation that severely degraded Al-Qaeda’s and their Taliban hosts’ capabilities. Their efforts demonstrated America’s resolve and bolstered citizens’ confidence at home. The mission proclaimed to enemies that the United States would go to great lengths to avenge and prevent an attack on its homeland. More subtly, this strategic operation’s success redeemed Eagle Claw’s failures and served to validate United States special operations capabilities—laying a strong foundation for the twenty plus years of conflict that have followed.

The quiet nature of Edmunds’ and Stonesifer’s work meant their final stories were left untold, and with the passage of time come faded memories buried under the weight of fresh sacrifices. Let this nation strive to remember two fine American Soldiers, Jonn Joseph Edmunds and Kristofor Tif Stonesifer, who perished for a cause larger than themselves. They courageously gave their all when America called, and their impact will continue to be felt for years to come.

The Department of Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review cleared this article for Open Publication, case #24-P-0216.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Notes:

1. Stonesifer was a Private First Class (PFC) during the mission and was later promoted posthumously to Specialist (SPC); his final rank is used throughout this article.

2. Casualty clarifications: The first death as part of Operation Enduring Freedom was Air Force Master Sergeant Evander Earl Andrews who died on October 10, 2001, as the result of a forklift accident in Qatar. The first combat-related deaths were Edmunds and Stonesifer in Pakistan, while directly supporting the first direct action into Afghanistan on October 19, 2001. The first American killed in action in Afghanistan was CIA Paramilitary Officer Johnny Micheal Spann on November 25, 2001, at the Qali-Jangi fortress near Mazar-e-Sharif.

Sources:

“Remembering The 2 Army Rangers Who Were The First Combat-Related Deaths Of The Afghan War,” Task & Purpose (https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-rangers-oef-first-casualties/). Author Paul Szoldra provides a brief overview of Edmunds and Stonesifer’s unit and their mission. However, his key source (Leigh Neville’s Special Forces in the War on Terror, p. 36) is understandably not informed.

“Wyoming troop deaths 20 years apart bookend Afghanistan war” Military Times (https://rb.gy/ajr4xz). This article interviews Jonn Edmunds father and describes that the first and last casualties of the war came from Wyoming.

CPL Jonn Joseph Edmunds (1981-2001) (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5898173/jonn-joseph-edmunds) — Find a Grave Memorial. This site provides a brief synopsis of Jonn Edmunds life and contains entries from his family, friends and just everyday Americans who honor his service.

Kristofor Stonesifer (http://rstonesifer.com/kris/index.htm) This family run website contains a wealth of information on Kris to include his personal writings, eulogies, photos, and early videos.

Kristofor T. Stonesifer — Specialist, United States Army (https://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/ktstonesifer.htm)

Evander Earl Andrews — Master Sergeant, United States Air Force (https://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/eandrews.htm). This website page describes Andrews and his family. At the time of his death, he was preparing an air base in Quatar that was key to establishing the air bridge for Operation Enduring Freedom.

Johnny Micheal Spann — CIA (https://www.cia.gov/legacy/honoring-heroes/heroes/johnny-micheal-spann/). This site briefly speaks to Spann’s early life, time at CIA and his final mission.

CNN.com — Official: Kitty Hawk fully loaded for combat – October 17, 2001 (https://www.cnn.com/2001/US/10/17/ret.kitty.hawk/index.html). Two days prior to the mission, the Department of Defense announced the presence of the Kitty Hawk and its embarked special operations forces. This release compromised the operation as the enemy could easily deduce potential target sets and respective infiltration routes.

Home | United States Army Rangers — The United States Army (https://www.army.mil/ranger/). This website provides the reader with a modern overview of the Rangers.

Operation Eagle Claw — Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Eagle_Claw). On April 24, 1980, the United States military launched Operation Eagle Claw to rescue American hostages being held in Tehran, Iran. Following mission abort, a helicopter experienced a brownout at desert landing strip known as Desert One and drifted into a C-130 aircraft, exploding on impact, and killing eight servicemen. This disaster led to the creation of the United States Special Operations Command.

Wind of 120 days — Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wind_of_120_days). This site briefly describes the annual four-month long sandstorm phenomenon. The strength and duration of these storms move the sands of the desert, creating dunes and leaving behind extremely fine dust, the source of dangerous brownout conditions.

Kaplan, Robert D., Soldiers of God, with Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Vintage Partners, 2001. This pre-9/11 non-fiction provides a thorough survey of the stark terrain that the task force faced. On page 204, mujahid Mohammed Akbar joked, “This is Baluchistan, but we call it Powderistan.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Chris Sorenson was a Special Operations Soldier who has first-hand knowledge of Edmunds’ and Stonesifer’s mission. He served in the 75th Ranger Regiment, 1st Special Forces Group, United States Army Special Operations Command, and other career assignments. Chris is a member of the Special Forces Association (Chapter 28) and lives in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

The author would like to thank his daughter Sara A. Sorenson for her editing assistance in making Edmunds and Stonesifer’s story more suitable for non-military readers.

Chapter 78,

Edmunds and Stonesifer were in my Platoon 19 Oct, 2001. I was on the USS Kittyhawk in October 2001 during the invasion with Company (-) B 3/75 (1st Platoon).

I was manifested on that Chalk on Bird 1 (UH-60 Blackhawk). I was scratched as an attachment from 1st Squad, as was one of my SAW Gunners in Bird 3.

3rd Squad and Weapons Attachments were tasked with two USAF Combat Controllers that took my place and my SAW Gunners. I was to be to the right side of the Left Door next to the Mini Gunner.

The CCT that took my place was injured as was SSG James Parke’s men in the crash. Jonn and Kris died instantly. We were on comms from the Carrier. We heard it real time. After, we continued missions until our mission changed at the end of October into November.

Anyway, Thank you for the email and magazine.

Jimmy Pera

18Z5U (ret)

Company Operations SGT

A 5/19 and C 1/19