AN EXCERPT FROM:

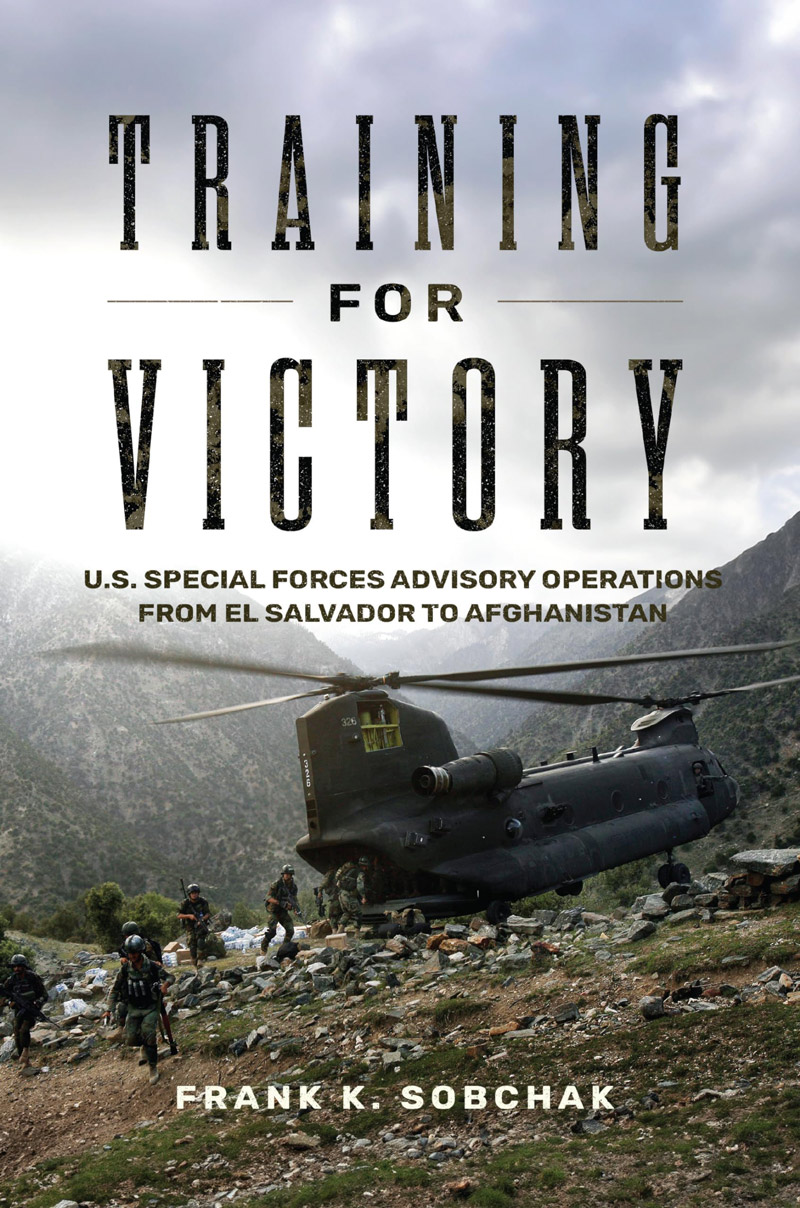

TRAINING FOR VICTORY:

U.S. Special Forces Advisory Operations from El Salvador to Afghanistan

Editor’s note: Since this book’s subject is one of deep, but easily understandable, analysis, the focus is on the Security Force Assistance role of SF in 5 significant and successful operations in El Salvador, Colombia, The Philippines, Iraq, and Afghanistan. This is an example from the book that demonstrates the methodology while illuminating fascinating insights into each [mission]. Five areas were studied: Partner-to-Advisor Ratio, Consistency in Advisor Pairing, Advisor Language Training and Cultural Awareness, Advisor Ability to Organize Host-Nation Unit, and how much advising side-by-side in combat was allowed. The measure of success was combat effectiveness, judged by Fighting without Advisors Present, Night Fighting, Conducting Multiday Combat Operations, and Performance against the Enemy in Combat, combining to yield a rating of Overall Combat Effectiveness. This example, from Iraq, covers only the first three areas to demonstrate the author’s thoroughness, depth of knowledge, and ability to get his point across.

This all results in the author’s fascinating findings, which will likely be considered in the further refining of the SF structure and planning.

You should get this book for the full story.

By Frank K. Sobchak, TRAINING FOR VICTORY: U.S. Special Forces Advisory Operations from El Salvador to Afghanistan; Published by the Naval Institute Press, pages 110-123, used with permission.

Chapter 4

“We Have Killed Many Men Together”

The Iraqi Special Operations Forces, 2003–2011

BACKGROUND

Operation Iraqi Freedom and Regime Change

THE UNITED STATES’ involvement in Iraq was limited and fleeting before the Gulf War of 1990 and 1991. That conflict, which aimed to eject Iraqi forces from Kuwait and preserve the flow of oil, destroyed most of the military but left its authoritarian leader, Saddam Hussein, in power. After the war Iraq remained a central part of U.S. foreign policy, and a long period of hostilities persisted, often punctuated by U.S. airstrikes. For his part, Saddam brutally repressed minorities that had risen up against him in the final days of fighting, resulting in the establishment of no-fly zones in northern and southern Iraq. The northern zone eventually grew to become a de facto Kurdish autonomous region, and many Green Berets from 10th Special Forces Group assisted in the initial humanitarian mission, Operation Provide Comfort, while the zone was being established.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, fundamentally altered U.S. policy toward Iraq. No longer content to pursue the status quo of containment, the administration of George W. Bush opted for a strategy of regime change followed by occupation and democratic elections. U.S. special-operations forces played an outsized role in the 2003 invasion, with the Middle East–oriented 5th SF Group conducting unilateral operations and supporting U.S. conventional forces, and the European-oriented 10th SF Group pairing with Kurdish Peshmerga fighters. While the invasion quickly crushed the ramshackle Iraqi Army and dissolved all central authority, its insufficient troop force and poorly planned reconstruction phase left the country without viable replacements. A capable insurgency quickly filled the void. Coalition errors that included disbanding the Iraqi security forces and banning Saddam’s Ba’ath Party accelerated the growth of that resistance.

Creation of the Iraqi Special Operations Forces

In the aftermath of the catastrophic Coalition Provisional Authority Order 2, which disbanded the Iraqi security forces in their entirety, the United States and its allies were faced with the daunting task of completely rebuilding the Iraqi police, military, and intelligence services. While the U.S. Army began building Iraq’s new army, the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force–Arabian Peninsula (CJSOTF-AP) initially focused on kill/capture missions to round up the principal leadership of the Saddam regime. But in October 2003 the CJSOTF was tasked with forming the new army’s 36th battalion after leaders of Iraq’s five top political parties complained that they were being sidelined in U.S. efforts to rebuild the Iraqi security forces.

Rather than a regular infantry battalion, the CJSOTF decided to build an SOF partner force and named the unit the 36th Commando Battalion. The Commandos were patterned after the U.S. Ranger battalions in organization, equipment, and missions and would operate as a platoon or company but muster all the companies together for larger missions. Operations would occur at night and target top-tier threats. As the Commandos were being recruited, trained, and organized, in parallel the CJSOTF organized the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Force (ICTF), which would have similar capabilities to the U.S. Army Special Forces Commander’s in-Extremis Force (CIF) companies. Over time those two units grew from a modest assemblage of soldiers into a division-sized force known as the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF). Special Forces from every active-duty group were involved in the advisory effort, although 3rd (which focused on U.S. Africa Command), 5th, and 10th SF (ISOF). Special Forces from every active-duty group were involved in the advisory effort, although 3rd (which focused on U.S. Africa Command), 5th, and 10th SF Groups carried most of the burden. The ISOF became the centerpiece of the SOF advisory effort and was resourced intensively from its inception in 2003 until December 2011, when U.S. forces were withdrawn from Iraq.

The ICTF conducts a training exercise, 2018. DVIDS photo by Pfc. Anthony Zendejas, Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve

THE ADVISORY EFFORT

Partner-to-Advisor Ratio

The ISOF experienced considerable growth over its development. At first the elite Iraqi forces comprised two disparate battalions, the 36th Commandos and the ICTF, but they were combined into a brigade in August 2004 to share common headquarters and support elements even while they maintained their distinct organizational identities and missions. A support battalion was added to fulfill logistics needs and a recce (recon) squadron was created to handle human intelligence and urban reconnaissance. To ensure force regeneration as the organizations took losses and soldiers retired, an Iraqi-led training center, later named the Iraqi Special Warfare Center and School, was also stood up. In total, the elite forces were authorized 1,600 personnel, inclusive of operators and support elements, from late 2005 until mid-2007.

In May 2006 the CJSOTF and Iraqi government agreed that the ISOF should be expanded by forming a second commando battalion that would include regional companies in Anbar, Basra, Diyala, and Mosul provinces. With all the elements of the 1st ISOF Brigade garrisoned in Baghdad and recognizing Iraqi forces would not always be able to rely on U.S. aircraft to move around the country quickly, CJSOTF advisors believed that regional companies would allow the ISOF to react quickly to threats across Iraq. This change resulted in dramatic expansion of the ISOF to 4,800 authorized personnel, but the Iraqi Special Warfare Center was incapable of meeting the demand to grow that quickly. As such, actual growth was extremely slow, and only the Basra and Mosul companies were activated by January 2008.

Near the end of 2007 U.S. and Iraqi SOF leaders decided that the regional companies would be expanded to battalions and that those units would form the 2nd ISOF Brigade, which was activated in July 2009. That growth propelled the ISOF to 8,500 personnel, but that size was purely hypothetical as the stand-up of the regional companies was still not completed. Despite pressure from Iraq’s political leaders, both U.S. and Iraqi SOF officers were reluctant to mass-produce the elite forces, and actual ISOF personnel strength hovered at around 59 percent. By the time of the U.S. withdrawal in 2011, each regional battalion was in actuality closer to a company-sized unit.

Special Forces advisors and Afghan commandos conduct a combined multiday clearing operation, Kandahar Province, 2009. U.S. Army Combat Camera

Advisor Commitment

The SF advisor ratio in Iraq was relatively constant, and as the ISOF expanded the advisor commitment grew to match it. This was likely because Iraq was considered the United States’ main effort in the larger global war on terrorism. That consistency makes it easier to explore the commitment to each of the two main components of the ISOF and then normalize that over time to reflect an overall ratio.

Iraqi Counter Terrorism Force

The ICTF was made up of three operational troops; a support element with vehicle drivers, gunners, and mechanics; a headquarters section; and one “recce” or reconnaissance troop. Each of the operational troops was assigned twenty-two Iraqi soldiers, and they followed a red-amber-green cycle with one troop in each phase. Phases lasted ten days, allowing ICTF members to go on leave (red), train (amber), and then conduct combat operations (green). Advisors mirrored the Iraqi cycle, and when an ICTF troop entered the leave phase, their partnered ODA either took time off or assisted advisors of other troops as required.

Each ICTF troop was paired with an ODA of SF advisors, a substantial commitment. This was accomplished by having a U.S. CIF troop (which was composed of three ODAs) paired with the ICTF battalion. Only CIF units advised the ICTF. It is worth noting that this ratio is roughly 1.83 to 1, massively larger than the doctrinal ratio of between 50 and 75 to 1. The ratio might have been even higher during the initial stand-up of the organization, reaching or exceeding a 1-to-1 ratio, but interviews I conducted with many officers and noncommissioned officers who worked with the ICTF during this period were not able to corroborate this data.

Commando Battalions

When the Commandos initially stood up as the 36th Commando Battalion, an SF company headquarters (AOB) and two full strength SF ODAs—approximately thirty four personnel—served as advisors. That initial phase lasted from approximately October 2003 until June 2004, when an additional ODA was added to support the battalion as it became fully operational (with advisors increasing to forty-six personnel). The new ratio was short-lived as the demands of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as the missions in the Philippines, Colombia, and elsewhere far exceeded the number of SF soldiers in the Army. The additional troop requirements dropped by the end of 2004, when the partnership stabilized to two ODAs working with the battalion.

Such a pairing allowed the SF advisors to match the cyclical leave-training-operations cycle of the Commandos with one ODA paired with the company conducting training while the second paired with the company conducting operations. Because one Commando company was always on leave, this resulted in a ratio of one ODA paired with an Iraqi Commando company of 120 soldiers, a matching that persisted throughout the remainder of the conflict. That ratio (ten to one), is considerably higher than the doctrinal SF ratio of one ODA advising a host-nation battalion.

As each regional Commando company was stood up, an ODA was assigned to advise it. Such a commitment matched the ratio already in place and reflected the opinion of CJSOTF leaders that they should duplicate the pattern for continued success. However, the actual ratio of Commandos to advisors was slightly smaller than the original assignment because the regional companies had one platoon of soldiers always on leave, with their other two platoons in a training-and-operations cycle. Based on the documents detailing numbers of active troops and interviews with advisors, none of the regional Commando units expanded much beyond company size before the U.S. withdrawal in 2011.

Assessment

The overall partner-to-advisor ratio for the Iraq case study calculates as 6.2 ISOF soldiers per SF advisor (see figure 4.1 for the monthly averages).12 In terms of assessing that impact, there were advisors who had served on other missions studied in this book, and they observed firsthand the effects of different partner-to-advisor ratios. Of those, there was near-universal agreement that decreasing the ratio had a positive impact on the combat effectiveness of the unit they trained, and not a single advisor thought that a higher ratio was better.

LRB members conduct helicopter-infiltration training with Special Forces advisors, Fort Magsaysay, Philippines, 2008. (Courtesy SF advisor)

Consistency in Advisor Pairing

There was considerable consistency in advisor pairing with the ISOF. For the ICTF, only two SF companies advised the unit for the first three years of its existence. The decision to minimize the number of advisors was centered on the fact that the ICTF was considered Iraq’s national-level counterterrorism force. As such, it should be paired only with an equivalent capability within the U.S. effort: the Special Forces Commander’s in-Extremis Force (CIF) companies. B Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group, stood up the organization and served as their sole advisors for the first eighteen months of the unit’s existence. As a CIF, the company’s organization differed slightly from regular SF companies and was instead based around two troops of roughly thirty-six SF operators each. For those eighteen months the two troops of the company did back-to-back rotations, switching out every 120 days. Such a cycle was quickly deemed to be too grueling, and the 5th Special Forces Group CIF, A Company, 1st Battalion, was added to the rotational cycle in March 2005. Each one of the two troops in those two companies cycled through 120-day rotations for the next year.

Even though the rotations were shorter than conventional yearlong rotations, they were physically and emotionally brutal for the advisors. One advisor noted that he submitted 118 combat operations for approval during an average four-month rotation, leaving only two nights without a mission. Each operation was complex, with multiple structures to be assaulted and almost always follow-on operations conducted the same night. One atypical fifteen-hour combat cycle in 2005 involved the rescue of an Iraqi Army general who was an al-Qaida hostage and then four follow-on missions, including the capture of Number 11 on the theater high-value target list. Thus in March 2006 even the two-Group cycle was determined to be too arduous, and all the other CIFs in U.S. Army Special Forces Command (C Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group—which stood up the LRR, C Company, 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group, and C Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group) were added to the rotation. Even then, however, the 3rd Group and 5th Group CIFs were considered the primary advisors, and each company would deploy once in the annual cycle. One of the other three CIFs would deploy for the other four months of the year so that each of those companies would deploy once in a three-year cycle. This rotation persisted for the remainder of the conflict.

Like in the Philippines, the assignment of the CIF to the ICTF advisory effort greatly increased the consistency of advisor pairing for a variety of reasons. First, because there were only five CIF companies across the entire U.S. Army, there was an extremely small pool of personnel to pull from to serve as advisors. Second, those companies had an extremely stable set of assigned personnel. Individual advisors would often stay within the same CIF company for years, some never conducting a permanent-change-of-station move. The relative stability occurred because CIF companies were designed to be kept on call to respond to regional hostage crises or similar missions, and the members of each company received considerable specialized training. An SF soldier without that training could not be assigned to those companies.

The Iraqi Commando battalions in the ISOF, first the 36th and then the regional battalions, experienced a similar consistency in advisor pairing. A vast majority of the ODAs that served as advisors to the Commandos came from 5th and 10th Special Forces Groups, the two organizations that provided the headquarters for CJSOTF-AP. For the first three deployments, 5th Special Forces Group worked with the Commandos: initially teams from 1st Battalion, then 2nd Battalion, and then the same teams from 1st Battalion returned as advisors on the third rotation. Only when the SF soldiers on those ODAs started to become burned-out by back-to-back rotations were other SF Groups added to the mix. During that phase considerable effort was made to pair the same advisors with the same Commando unit, rotation after rotation.

Major General Fadhil al Barwari, commander of the 1st Iraqi Special Operations Forces Brigade, with Sgt. Maj. (Ret.) Ron McDaries, 2014 Courtesy Sgt. Maj. Ron McDaries (Ret.)

Although initially there were no special qualifications for an ODA to pair with the Commandos, in 2006 Special Forces CIF companies and teams became the primary set of advisors. Like in the ICTF, this greatly increased the consistency in advisor pairing because the CIF requirement vastly limited the potential advisory pool. There was also considerable personnel stability within the ISOF, and many Iraqis stayed within the organization for the duration of their careers. At times new Iraqis were brought in to imbalance the sectarian equilibrium of the ISOF, but the organizational culture minimized those impacts and personal and professional factors motivated those already part of the unit to stay.

There are numerous anecdotal reports about how frequently the various elements of the ISOF were paired with the exact same advisors. One advisor noted that an SF teammate had served on four different ICTF rotations and then retired. After his retirement, he returned as a contractor to continue working with the ICTF, supporting them in their fight to recapture Mosul in 2016. Another participated in eight combat tours in Iraq, acting as direct advisor to ISOF units during four of them, while during the other tours he supported and interacted with the ISOF. This meant the same advisor worked with the same Commando battalion for thirty-two months (nearly three years) out of a possible eight years. One advisor, whose exploits became legendary in the SF community, served with the ISOF for three years on five straight rotations during assignments to both 5th and 10th Special Forces Groups. He worked with the ISOF so often that other teams joked that they had to sign for him as part of the property handover as they changed out in between missions. Such consistent pairings were more common than not, and one SF company worked with the same ISOF unit for more than seven years. Their only breaks from the coupling were when they returned to the United States, allowing the SF advisors to see their Iraqi partners mature from their positions as captains commanding companies to generals leading the entire organization.

Because of how consistently many advisors were paired with the ISOF, deep friendships often developed with the soldiers and officers they advised. Maj. Gen. Patrick Roberson, who completed four advisory rotations with the ISOF, noted that he had first met Fadhil Jalil al Barwari, the unit’s future commander, in 1996. This time distortion occurred because Roberson commanded an ODA during Operation Provide Comfort, which delivered humanitarian and military assistance to Kurdish factions after the first Gulf War.

At that time, Barwari was serving in a Kurdish Peshmerga militia and met numerous SF soldiers rotating through northern Iraq. During Roberson’s deployments, his long-term connections with Barwari helped him pick up where he had left off on prior rotations, greatly facilitating growth in unit capabilities.

Assessment: “We Have Killed Many Men Together”

Nearly all the SF soldiers who worked with Iraqi Special Operations Forces believed there were considerable advantages to consistently pairing with the same Iraqi forces. It reduced the start-up time of each mission, allowing the advisor to pick up where they previously left off rather than start anew.

One advisor noted that for the first two years of his work with the ISOF his unit did four-month rotations. That meant he knew that when he finished each deployment, he would be back working with the same Iraqis in eight months at the most. “Because it was the same face coming back, they knew who you were, they trusted you, they’ve been in a room with you in a gunfight before. You just picked up where you left off. There was no dogs-sniffing-each-other’s-butts.”

Within a few days they were back on track, executing complex missions. Another advisor pointed out the differences between the SF effort with the ISOF and the advisory effort with the rest of the Iraqi Army. To him the ISOF consistency created a coherent campaign plan but the conventional-forces effort building other Iraqi forces was akin to fighting the war in Iraq with a different plan each year. “Every single year was just start over. It is all new Americans, and most of them have never been there. [Meanwhile] the Iraqis haven’t gone anywhere, and they knew how to navigate that environment.”

Consistency also created personal relationships and trust that made it easier to work through issues that impeded progress.

Sgt. Maj. Ron McDaries served as an advisor during three rotations and transitioned to contractor work after he retired. In 2014 he was still in Iraq as a contractor with the U.S. State Department as ISIS marched toward Baghdad. His supervisors were alarmed that there was no formal security where they were based and asked him if he could help. McDaries said that he knew General Barwari and asked for his supervisor’s phone to set up a meeting. Much to his supervisor’s surprise, Barwari invited them to his home, and when they arrived the general walked past the higher-ranking U.S. embassy official and gave McDaries a big hug, saying, “This is my brother. We have killed many men together and drunk many beers.” Even though it had been several years since the two had seen each other, Barwari did not hesitate to offer McDaries whatever support he needed, including providing an ISOF element for security.

A few dissenting voices noted that while they agreed in principle that consistency was important there could be exceptions when that pairing ought to be broken. Consistency could be a double-edged sword: if an ODA was not skilled at teaching and training or individuals on the team were bad at establishing rapport, then pairing that unit with the same host-nation forces would likely have adverse effect.

Others posited that some ODAs had life cycles, wherein team members would have personal issues or became burned out after multiple rotations and their performance would drop.

In such exceptional cases it made sense to break the bond of consistency. Overall, consistency in advisor pairing with the ISOF was high. Across multiple rotations the efforts of CJSOTF leaders and assignment of the CIFs to work with the ISOF greatly limited the pool of advisors and resulted in frequent return pairings. As one advisor noted, “continuity is better than gold. [It] is absolutely how you shape a force and ensure that they are responsive to our requirements and our objectives…It is instant trust, credibility, and, most importantly, influence.”

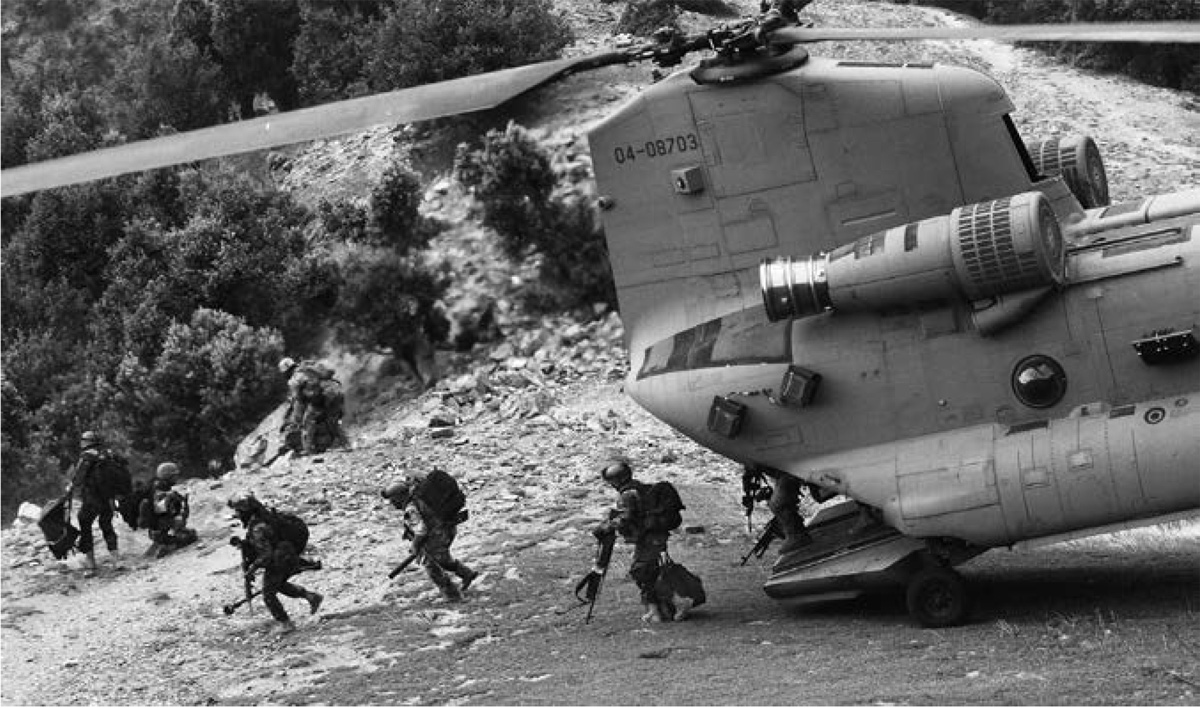

Afghan commandos with Special Forces advisors disembark a CH-47 Chinook helicopter during a combined raid against fortified insurgent positions, Uruzgan Province, 2009. U.S. Army Combat Camera

Advisor Language Training and Cultural Awareness

The demand for Special Forces operators in Iraq far exceeded what the Middle East–oriented 5th Special Forces group could provide. As one former Group commander noted, even if the entire group had been deployed for the duration of the war and its members never returned home, it still could not have met the needs of the theater commander.

Because of its connections with the Kurds after the first Gulf War, 10th SF Group, which was officially regionally and linguistically oriented to Europe, was selected to assist 5th Group in Iraq. The two groups shared roughly even responsibility as the CJSOTF-AP headquarters and contributed similar amounts of forces. Yet even those two units were not sufficient to the task, and every other active-duty SF group provided forces to help alleviate exhaustion from back-to-back rotations. Of all those groups involved in the mission, only 5th Group was officially oriented to the Middle East, focused its training on regional languages, and had extensive cultural experience.

While 5th and 10th Groups took the lion’s share of troop commitments to Iraq, when examining the contribution toward the ISOF—only a portion of the CJSOTF-AP mission—the assessment becomes more complicated. The 3rd Group CIF, regionally and linguistically oriented toward Africa, stood up the ICTF and had a monopoly on pairing with the organization for its first eighteen months of existence. After that the 3rd and 5th Group CIFs shared equally in pairing with the ICTF until mid-2006, when the other three CIFs were added to the rotational cycle. Rather than share the advisory responsibility equally among the five CIFs, 3rd and 5th Groups were each given one-third of the partnership while the other three CIFs shared in the other third of the deployment time. At the macro level this means that 5th Special Forces Group, the only regionally oriented organization, advised the ICTF for less than a third of its existence.

The history of the Commandos’ partnership is similar. While they were stood up by 5th Group, 10th Group rapidly fell in on the advisory cycle, and the two groups worked nearly equal amounts of time with the Commandos. By 2006 operational pressures resulted in the Baghdad-based Commando battalion being rotated primarily between CIF units on a ratio that matched the ICTF. As a result the Middle East–oriented 5th Special Forces Group advised that Commando battalion for roughly a third of its existence. Because the regional Commando companies (later battalions after the organization grew again) were not advised by CIF elements, they were shared in approximately even proportions between 5th and 10th Group teams.

When consolidating this data it should be noted that even though the ICTF was technically a battalion its personnel size was much closer to company strength. The regional companies, when combined, came close to the personnel strength of the Baghdad-based Commando battalion. Altogether the driving force on determining the degree of match with language training and cultural awareness was driven mostly by the Baghdad-based Commando battalion because it had the largest number of personnel. As noted, that meant a regionally oriented SF unit with matching language training and cultural awareness was only paired with the ISOF for approximately a third of the advisory effort. This leads to an overall assessment that the degree of match for language training and cultural awareness of the SF advisors to the ISOF was low.

AGLAN soldiers return from an operation against a FARC strongpoint, La Uribe, Colombia, 2006. (Courtesy the Official Colombian Military collection)

Assessment: “None of Us Spoke the Language in the Early Days”

Interviewees provided many different opinions regarding the importance of language training and cultural awareness. Although members of 5th Special Forces Group generally noted that they believed their regional orientation to the Middle East and knowledge of Arabic contributed positively to the development of the ISOF, this opinion was by no means universal, and few argued it emphatically. One SF soldier who spent most of his career in 5th Group and was trained in Arabic but later transferred to the non–regionally affiliated 10th Special Forces Group noted that there was little difference between the two groups. Across three years of deployments, he could recall only one occasion on which someone from another Group made a significant cultural error that affected operations.

Another advisor who started his career in 5th Special Forces Group, which was regionally oriented to the Middle East, but served in other groups as well observed, “Regional orientation only matters for the first trip. Once you have an advisor pool of special-operations forces that have deployed and built a relationship with that partner force, it doesn’t take long for special-operations forces to regionally orient [themselves]. That doesn’t mean that they are 3/3 in a language [test], but you can take a unit from 1st Group and put them in Iraq, and very quickly they understand the cultural, tribal, political, and social aspects of that environment and are able to operate effectively.”

Those that downplayed the importance of language training and cultural awareness provided various explanations. Some noted that even from its early days all ISOF units were fortunate to have many interpreters. Rather than relying on their own skills, U.S. advisors trusted interpreters to translate for them in training and in combat. Many also noted that over time the Iraqis came to take on many Western habits, traditions, and processes, which made it easier to communicate and work together.

By the middle of the eight-year mission, many of the Iraqis had learned conversational English and taken to wearing uniforms with pockets on the shoulders, replete with Velcro, and even copied the way the Americans would wear their Oakley sunglasses. They wore American baseball caps backward like the Green Berets did (and that, likewise, had annoyed conventional U.S. military leaders), carried the same flip knives as their advisors, and basically looked like mirror images of their U.S. partners.

Some had even picked up American vices, such as dipping tobacco—a far cry from the more common Iraqi habit of smoking cigarettes or shisha (water pipes). Others noted that the duration of the mission, coupled with consistently pairing with the same ISOF units, resulted in close personal contacts that went beyond a simple capacity to communicate in Arabic. While the lack of language skills might have impacted the first rotation, by the second it was negligible. By the third or fourth rotation, some advisors had worked with the same Commandos so often that they knew how their Iraqi partners would react or behave in a certain situation, which effectively precluded the requirement for verbal communication.

Some senior advisors noted that the ability to build rapport—which they argued was critical to having a positive impact on a host-nation unit—is a personal skill that was not always correlated with language training or cultural awareness. They posited that the two skills were completely independent from one another and from rank. In fact, some leaders paired a more-junior SF soldier who had strong interpersonal skills and ability to build rapport with important host-nation elements rather than more-senior operators.

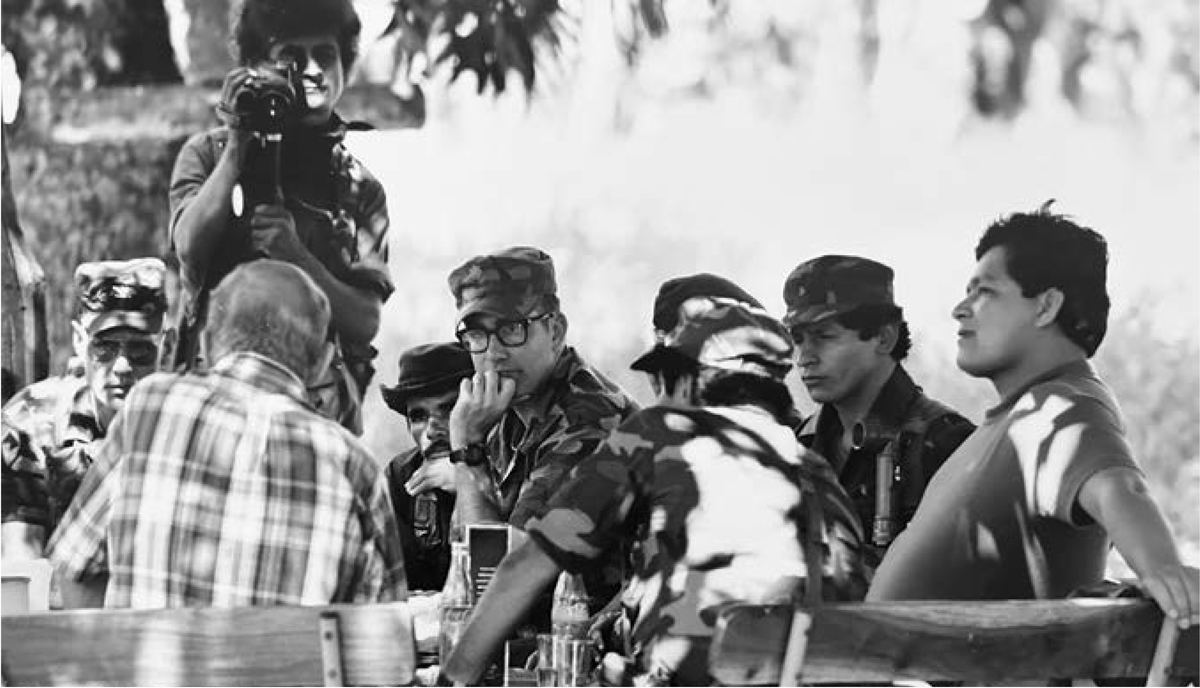

U.S. advisors attend peace talks between representatives from the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and Salvadoran government forces, Guazapa, 1992. Col. Mark Hamilton, then MILGRP commander, is on the left with sunglasses, then-major Francisco (Frank) Pedrozo is center with glasses, U.S. ambassador William G. Walker is in the checkered shirt with his back to the camera, and Fidel Recinos Alas, better known as Raul Hercules, commander of FMLN’s National Resistance, is leaning back in his chair, right. Courtesy Col. Frank Pedrozo (Ret.)

Another poorly kept secret was how few SF operators in 5th Group, the regionally oriented unit, were professionally proficient in Arabic. During the decade that SF soldiers advised the ISOF, the requirement to graduate from the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School language program was a 1/1 rating on the DLPT, which equates to elementary proficiency with only “sufficient comprehension to read very simple connected written material.” However, because of the complexity of some languages such as Arabic and Mandarin Chinese, that graduation requirement was frequently waived to 0+/0+, where one can “read some or all of the following: numbers, isolated words and phrases, personal and place names, street signs, office and shop designations. The above [are] often interpreted inaccurately.”

The 2012 U.S. Special Operations Command Language Regional Expertise and Culture Strategy Report noted that only 66 percent of Special Forces students could attain the 1/1 level, a statistic matched by anecdotal evidence gathered from interviewees and my personal experience.

During my four years in 5th Special Forces Group no more than a dozen SF operators at any given time had scored at the 2/2 level of limited working proficiency and no more than one or two had scored at the 3/3 level of general professional proficiency across the entire group of 54 ODAs (approximately 650 SF qualified personnel). As of April 2021, across all of Special Forces command, inclusive of the five active-duty and two National Guard groups and the headquarters, schoolhouse, and support elements, there were only 57 SF personnel who had scored at the 2/2 level or above on the DLPT or Oral Proficiency Interview on an Arabic dialect.

These scores show that the vast majority of those in the regionally oriented 5th Special Forces Group had only elementary proficiency in Arabic and led some advisors to posit that their language training did not significantly contribute to the mission because it was impossible to train to the level necessary to operate without interpreters. Even an SF linguist at a DLPT level of 3/3 in Arabic, they argued, would not be able to understand critical nuances, subtleties, and tone and would require the skills of a native speaker, such as an interpreter, to operate effectively. Six months of perfunctory Arabic training for five hours a day simply did not provide sufficient experience for functional proficiency.

Those who were less proficient in Arabic, such as one advisor who scored 0+/1 on the DLPT, noted that only a small subset of words were critical in the thick of combat. “None of us spoke the language in the early days. I went to school for Farsi. But by the end we could say the important stuff like Put the machine gun over there or You are our prisoner.”

Another advisor noted that he did not know any Arabic when he began advising the ISOF and instead spoke French and Serbo-Croatian. However, simply knowing the situation and the desired end state allowed communication because he could memorize the most important words and phrases. Such a perspective matches what other SF advisors in the Philippines observed—that while the specific language does not matter, knowing any language adds to one’s willingness and ability to learn other languages more easily and also gives the patience and cross-cultural communication skills important to advisors.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR —

Frank K. Sobchak, PhD, is a retired Special Forces colonel who served in various assignments in war and peace during a twenty-six-year military career. He is Chair of Irregular Warfare Studies at the Modern War Institute, U.S. Military Academy, a Senior Fellow at the Global and National Security Institute, University of South Florida, and a Fellow (contributor) for the MirYam Institute.?Dr. Sobchak is the coauthor of the acclaimed two-volume The U.S. Army in the Iraq War and has been published in the Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, Newsweek, Time, the Jerusalem Post, Defense One, The Hill, War on the Rocks, the Modern War Institute, and the Small Wars Journal. Sobchak has a PhD in international relations from Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He is married to his West Point classmate, Lt. Col. Iris Sobchak (Ret.), and they live in Holliston, Massachusetts, with their four children.

Leave A Comment