AN/GRC-109:

The First True Special Forces Radio

Gene Williams in the field in Vietnam in 1967, setting up radio for communication to A-Team base.

By Gene Williams

A-233 Ban Don ’66-’67; MACV SOG FOB-2 ’68

Originally published in the February 2015 Sentinel

Browsing eBay I stumbled across this item: a genuine AN/GRC-109. Time flashed back to 1965 and I just had to acquire it:

AN/GRC-109 radio, complete with instruction booklets.

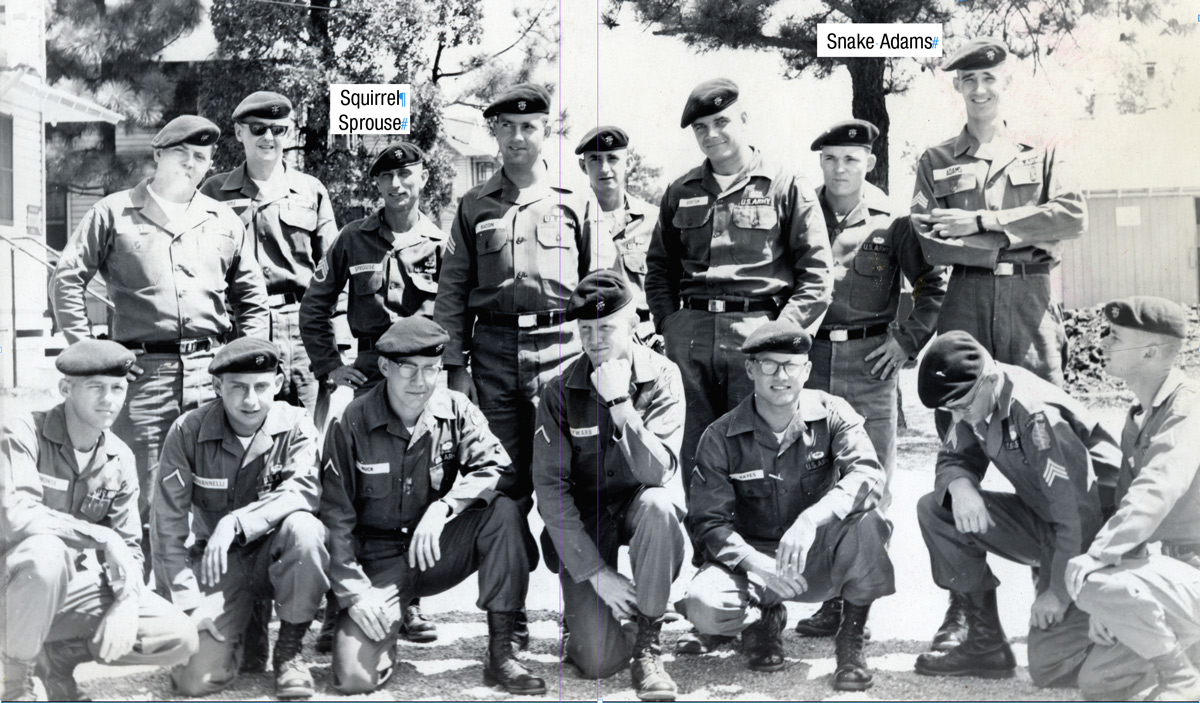

Why? In July, 1965, the new Special Forces Training Group commo class on Smoke Bomb Hill convened including myself and subsequent legends like Squirrel Sprouse and Snake Adams (both pictured below—author not pictured; note Snake’s healthy attitude—he was SF already).

July, 1965, SFTG commo class, Smoke Bomb Hill, Ft. Bragg: Snake Adams and company

We all were introduced to the AN/GRC-109 the next month. Here was a true piece of Cold War fighting black iron … sneaky, solid, menacing-looking … and heavy as a cannon ball. We carried it and its hand-cranked generator the AN-58 into Piscah National Forest for the December, 1965, final exercise. Lonny Holmes can attest to the weight of that generator; he toted it in the snow and ice for two weeks.

They were built for the Army from 1960 to 1964 but were the standard SF A-team radios from 1960 to the mid 1970’s. These radios were underpowered, required send/receive in Morse code, and were technologically behind the times by 1966, but utterly indestructible.

AN/GRC-109 radio with generator

The radio originated with the SSTR-1 OSS unit radios in WWII. In 1948 the CIA upgraded the SSTR-1, adopting a radio made by Admiral Corporation for use by guerrilla fighters and agents world-wide. It was called the RS-1. The RS-1 was used everywhere — Albania, Cuba, SE Asia, Tibet, China, Iran, Eastern Europe, Russia. It was versatile, modular, could be hidden even underwater, buried in the ground, air-dropped and was unbreakable. It could be used with any input voltage and load just about any antenna. And it had a “burst transmission” capability limiting time on air and helping negate enemy RDF. It was the Jeep of the radio world.

As the conflict in SE Asia began to accelerate in Vietnam and in Laos in 1960-61, the 7th SFG’s Operation White Star SF teams came under CIA opscom and used the RS-1. The Army soon realized it needed an equivalent radio and for once was struck with common sense — it simply adopted the CIA radio and re-labeled it the AN/GRC-109.

Sgt Terry Dahling in the 10th SFG. Note: Dahling was my predecessor as 1-0 of RT Delaware, FOB-2, Spring, 1968

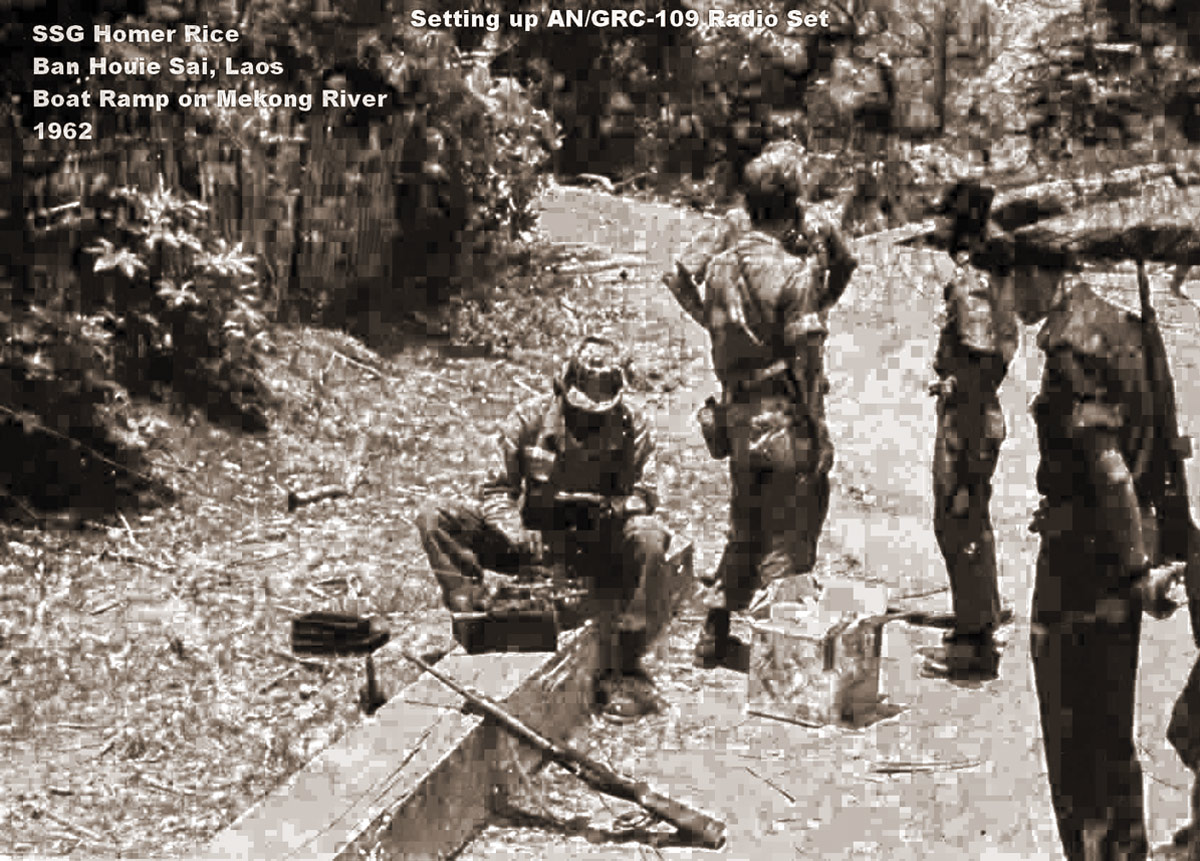

SSG Homer Rice, USSF, Ban Houie Sai, Laos, 1962 setting up the 109

The radio consisted of three different units:

(1) R-1004 receiver (CIA designation RR-2): For the tech minded it receives AM and CW. It is single conversion, superheterodyne receiver that could be controlled by a crystal 455 khz higher that the receive frequency. It has 6 valves – RF pre-amplifier, local oscillator/mixer, 2xIF amplifiers, AF amplifier and a BFO. It has a manual RF gain and could be used with headphones or a speaker. It could receive AM/CW signals ranging from 3000 KHz to 24 Mhz over three bands — 3-6 MHz; 6-12 Mhz and 12-14 Mhz.

(2) T-784 transmitter (CIA designation RT-3): This is a crystal controlled CW only transmitter which could be used via the built-in key or an external key. It could broadcast on freqs from 3000 Khz to 22 MHz in four bands. I had two valves: one for the crystal oscillator and one for the RF amplifier. It’s power output was 12-15 watts (3-14 MHZ) and 10-12W (15-22 MHz).

(3) Power Supply: There were three alternatives (a) PP-2684 Power Supply (CIA designation RP-1): The power supply was robust and could be switched to operate on every AC voltage in the world. AC input could range from 75 to 269 volts at anything from 40 to 400 Hertz. The supply line cord had wall unit adapters. It provided 6 volts AC for the transmitter and 1.3 volts DC for the receiver. It also could charge the battery. It could be powered by a gasoline generator or from the infamous hand-crank generator. (b) PP-2685 Power Supply: There was a second smaller power supply the size of the transmitter/receiver packages that was less capable. (c) AN-58 hand crank generator (CIA designation SSP-11): There were two models — AN-58 and the taller AN-43. No matter the model, you’d better put your most steroid-enhanced, anaerobic, muscle onto this.

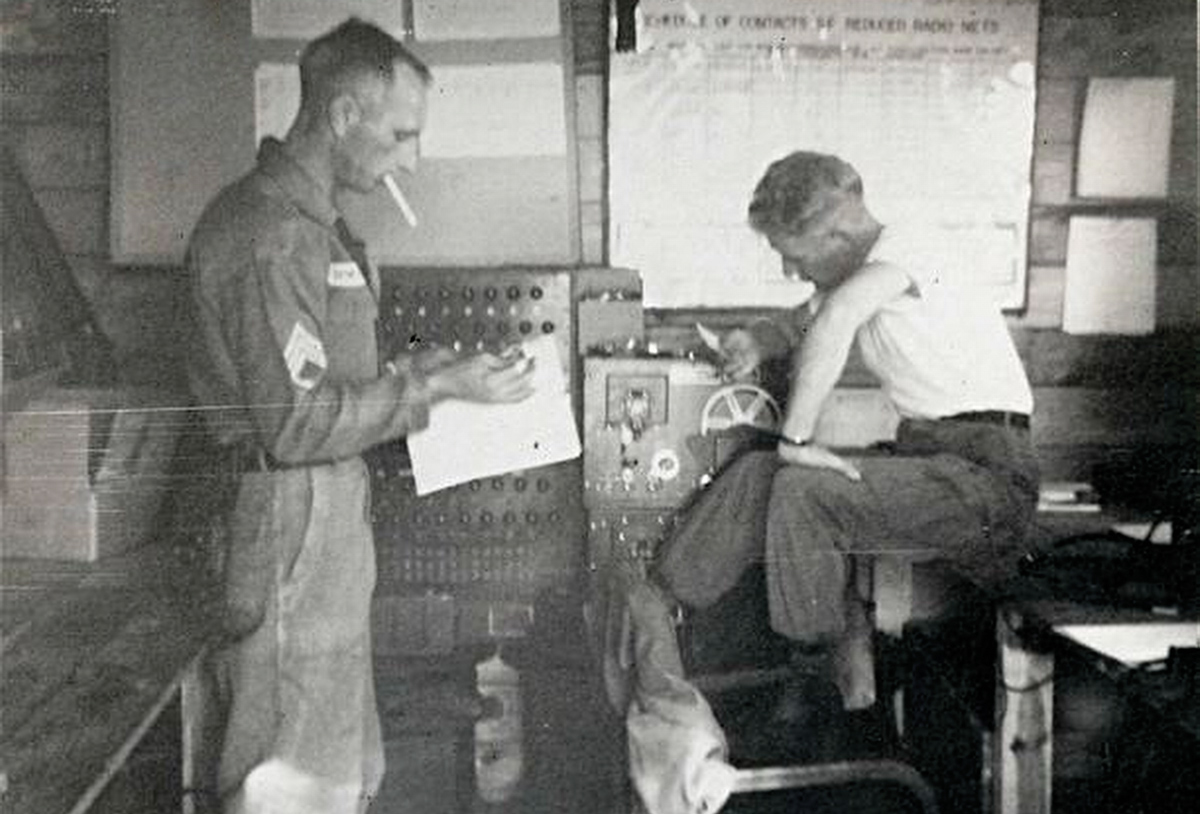

MSG Richard E. Peghram, 1964, Plei Mrong

Special Forces in Vietnam and Laos operated the AN/GR-109 mostly from hand-made dipole antennas, or long wires cut to frequency and tossed up into trees, or coat hangers or barbed wire. And it would transmit around the world if you needed it to. Though there was a built in Morse code key on the set, few used it. Most of us scrounged, stole, bought a “leg key.” The problem with operating in Piscah for that final exercise was the civilian ham radio operators. We were trying to communicate using 12 watts of power. The hams would hear the call sign, think it was some odd ham radio operator sending from the Solomon Islands or someplace and come bombing in on top of us with 10,000 watts of power. The “B-Team” often had to have three radio-men listen to the same transmission…then try to piece together the message. The B-team base camp for the Dec 1965 Piscah exercise is pictured to the bottom right; No AN/GRC/109’s — which were in a separate tent; but there again is Squirrel Sprouse looking very 82nd Airborne:

Squirrel Sprouse, B-Team, final SFTG training exercise, Fall-1965

In Vietnam at least by 1966 not a single A-Camp used the AN/GRC-109 for every-day transmissions. By that time SF had equipped its A-teams with civilian Ham Radio Single Sideband Collins KWM-2A transceivers and automatic keys (Bugs), great for bootlegging a Ham call sign, pretending to be “maritime mobile,” and bombing back into the USA to have a Ham operator patch you into the phone system there.

Also the A-team’s CIDG companies were usually operating within 30 km of their base and could communicate via standard PRC-25’s; MACVSOG teams by this time also used PRC-25’s, relayed by commo sites in Laos or Cambodia (such as Leghorn) situated on vertiginous unassailable heights.

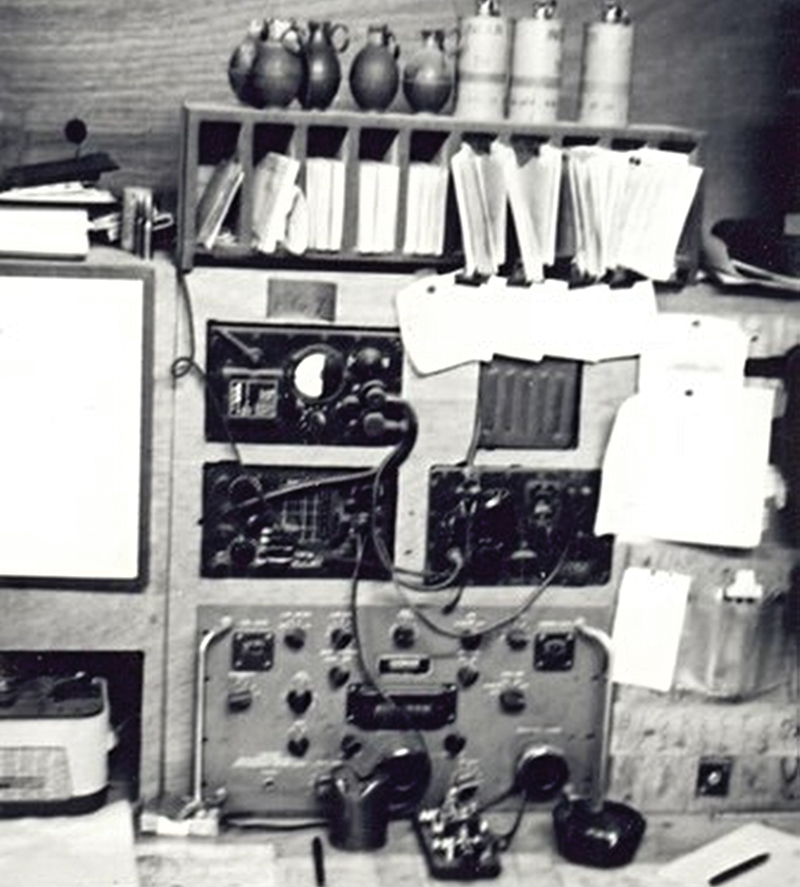

Yet every A-camp still had the AN/GRC-109 sitting in the commo bunker as a backup. Just looking at that black iron resting solidly on the desk was comforting. It wouldn’t break. It could be used as bullet-proof armor in a pinch. And it had an aura of, dare I say, romance with a pedigree connecting Special Forces troopers in Vietnam with the WWII OSS led guerrillas in France, Italy, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya and Vietnam itself.

Dak To commo bunker: Note the grenades to destroy equipment.

A typical “leg” key for sending Morse code in the field.

Semi automatic Morse code key, called a "bug," used by all teams in Vietnam for lighting fast team-to-team communication.

Notice I have mentioned communication by Morse code several times. Special Forces in Vietnam were perhaps the last large units in the world, certainly in the USArmy, to use Morse code for team-to-team communications. SF employed something else that was unusual too. The use of code required encrypting the messages. For this purpose, SF throughout the country employed “one-time” pads, probably the most extensive use of this unbreakable encryption ever.

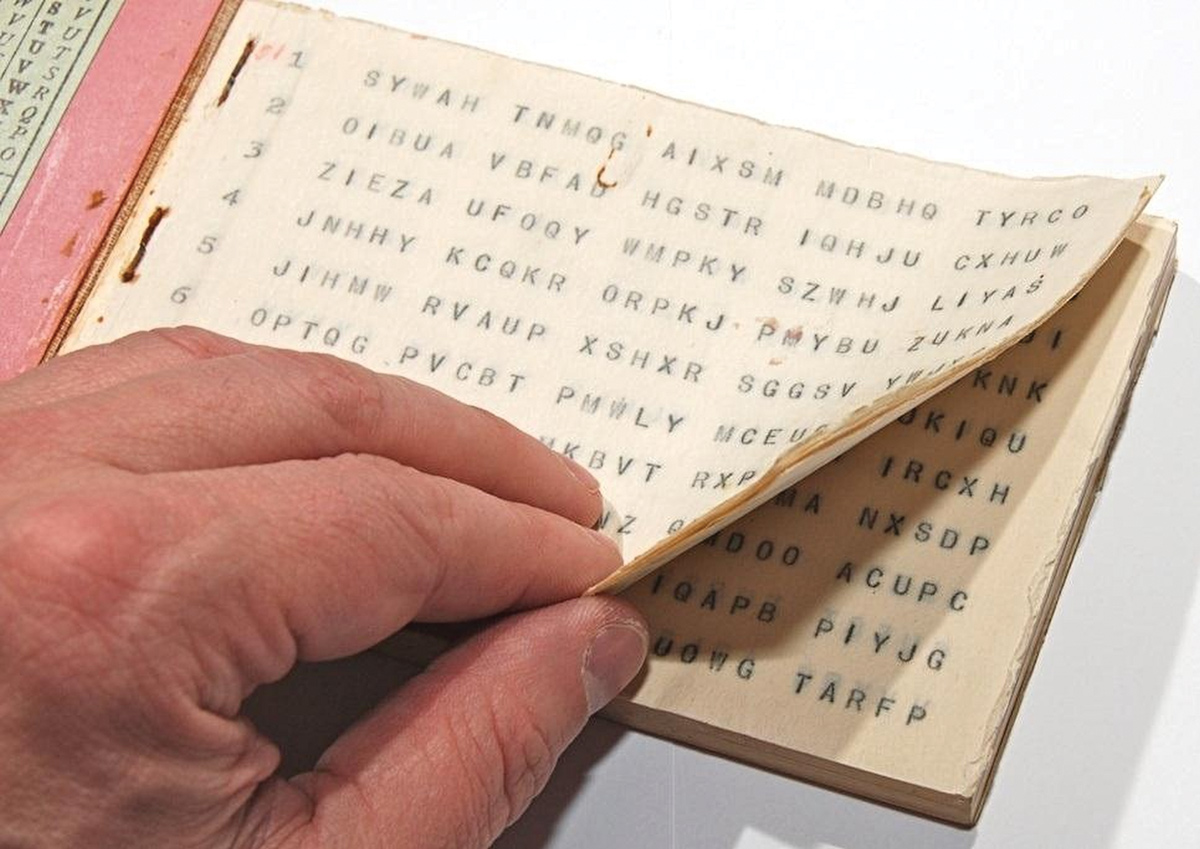

The “one-time” pads were produced in duplicate copies. Two teams needing to communicate each had one of the pad copies. Each sheet on the pad contained lines of randomly generated letters in groups of five. To encrypt, you wrote your message above the groups of letters, and then converted to a code letter by combining the random pad letter and the message letter, using a matrix. The receiving team reversed the process, and then both teams destroyed the “one-time’ sheet. Most 05B4S’ (Special Forces Commo MOS) in S. E. Asia during the war could encrypt and decrypt on the fly … they had memorized the conversion matrix.

Typical “one-time” pad with encryption matrix barely visible, extreme left. From http://www.cryptomuseum.com/crypto/img/301277/005/full.jpg

What finally happened to the An/GRC-109? In a way the radio marked the end of an era. It was designed for WWII behind-the-lines conditions; for 1,000 mile cryptic communications from autonomous units operating on their own with minimal direction from the “center.” That concept went away when you could call by voice to your commanders only 30 miles away. The need just disappeared, just as the authority for squad tactics controlled by a sergeant disappeared when a General could fly in and hover overhead in his helicopter. Still, the 109 was, and is, the acme of the genre.

Final word: I was posted to the Karachi Consulate in the mid-1970’s. The Consulate had been built in 1952 and while helping clean out the attic which had stuff stored for 25 years, I discovered a pristine RS-1. It was fully operational with hand-crank generator and a complete set of crystals and no property records. I chucked it. Buying this set makes up for that stupidity. I may donate it to the Special Warfare Museum but only after I play with it for a while.

Author, Gene Williams, Left - Herat, Afghanistan, 2006, Right - Ban Don, S. Vietnam, 1966

About the Author:

Gene Williams, and his twin brother Jack, come from a military family with a history dating back to the War of 1812. Their father, Lt. Gene Williams was a Pathfinder in the 82nd Airborne Division, 508th PIR and jumped into Normandy on D-Day. Unfortunately he was killed in action on June 20, 1944, before he could receive the message that he was the father of twin sons.

Gene and Jack both served in 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), Vietnam in the 1960s as commo men; Gene at Ban Don in 1966, then as a MACV-SOG 1-0 of RT Delaware at FOB 2 in Kontum in 1968, and Jack at Ben Het and Dak To in II Corps in 1968.

Friends of former Sentinel editor Lonny Holmes since their days at Fort Bragg. N.C., in late 1965-1966, both Gene and Jack have been significant past contributors to the Sentinel.

July 2014 — “The Vietnam Randall” by Jack Williams

December 2015 — “Tracking Down A Hero; the story of SGM James O. Schmidt” by Gene and Jack Williams

April 2017 — “The Last Pathfinder Company is History: Long Live History!” by Jack Williams

August 2019 — “D-Day 75th Anniversary: A Normandy Experience” by Jack Williams

Great story! I’d like to fill in the blanks. In late 1964 through early 1965, working for Major James V. “Beetle” Bailey, the 5th Group Signal Officer, as Signal Company Commander, I sent personnel to every camp to train Team 05Bs on the suitcase Collins KWM-2A (eventually designated, as best I remember, the AN/FRC-93). Credit Major Bailey for having chosen the Collins radio as the AN/GRC-109 replacement. !n my experience, Special Forces, in general, was reluctant to adapt and adopt conventional technologies. When I returned to Fort Bragg in mid-1975 to be the USAJFKCEN Signal Officer, I was surprised to learn that nothing had changed. The AN/GRC-109 was still the Team radio. This time, with the blessing of Col. Bob Mountel (Center G-3), and General Robert Kingston, I began a search for a replacement, visited the CIA’s S&T Directorate for an update on its state-of-the-art radios, obtained two man-pack radios, one from Harris Corp. and one from a British Company, for field tests at Fort Bragg, but I cannot report on the results, because I left the Center to take command of a Signal battalion. I will add a commo footnote. My predecessor had rejected an invitation from the NSA to develop an automated CEOI for Special Forces to replace the version that was manually generated at Group HQ. He had believed that it was “too conventional for SF.” I reopened the dialogue with the NSA, worked with representatives from active, Reserve and National Guard SF units to design an SF-specific format, and before I left the Center in June 1976, a prototype had been developed that would also replace one-time pads. SFC Angel Candelaria was my right-hand man on these projects, so when Col. Charlie Beckwith was looking for a “good commo guy” for his nascent Project Delta and called me, I lost Sgt. Candelaria and Col. Beckwith gained him. In the 1990s, having retired from the Army, and working at SAIC, I was, once again, involved in various communications projects. One, in particular, was under the auspices of DARPA funding: I was charged with developing the technical specifications for a multi-band, man-pack radio for Special Forces. Unfortunately, I do not know what DARPA did with that effort. Throughout my 20-year Army career and, later, as a Defense contractor, it seems that I was destined to play a small role in the evolution of SF tactical communications.

I used it in 1968 with the 6th SFG

We were using it in 7 SFG, 1976, both Bragg and Canal Zone. We cross trained the whole team to send & receive 4 groups/minute. Challenge was free falling it on operations–everyone had to jump a piece of it!