Across The Fence:

HAPPY NEW YEAR

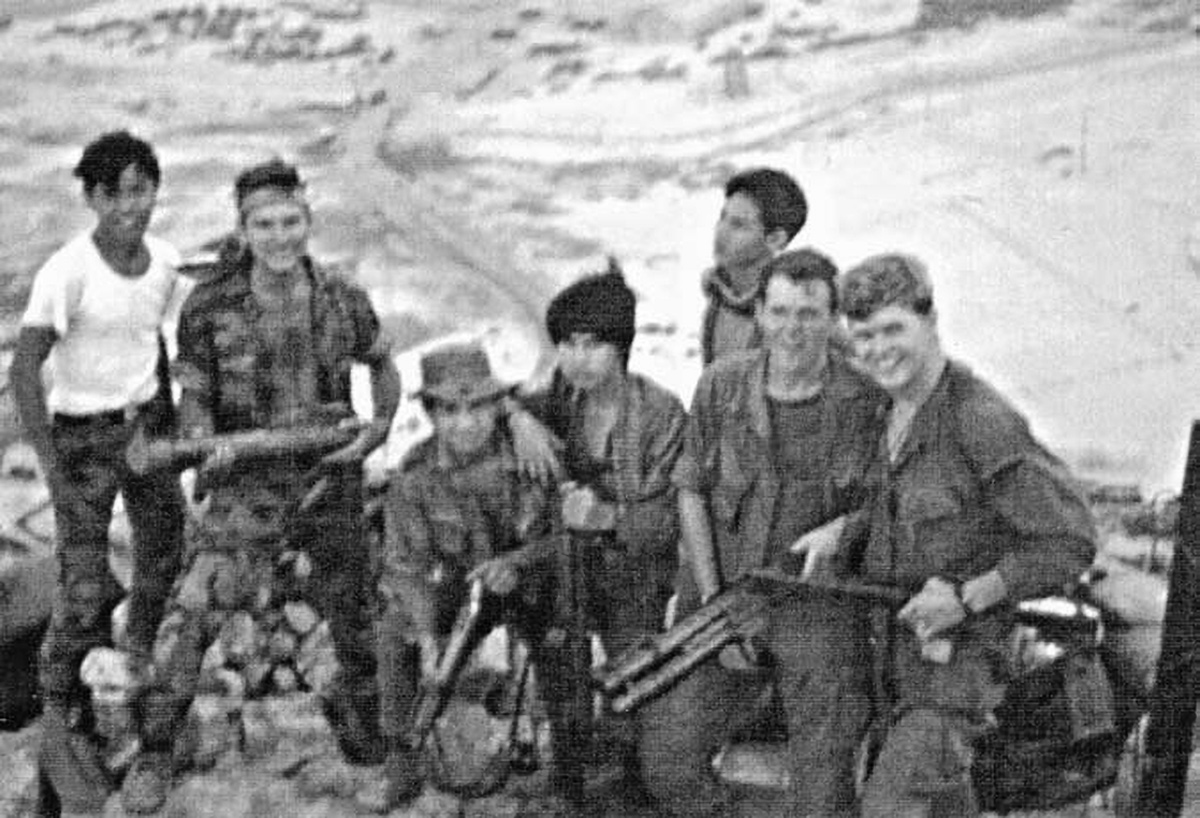

This is one of the few photographs of four ST Idaho One- Zeroes together with some of their South Vietnamese team members. From left, kneeling, Nguyen Van Sau — the Vietnamese team leader and counterpart to the One-Zero, Tuan — the M-79 grenadier, Cau and Nguyen Cong Hiep — interpreter. And yes, Hiep always wore those sunglasses, even in the jungle in the dark of night. Standing from left, Lynne M. “Blackjack” Black Jr., Don Wolken, Phouc — fearless point man for ST Idaho for many months, John S. “Tilt” Meyer and Robert J. “Spider” Parks. (Photo courtesy of Doug LeTourneau)

By John Stryker Meyer

Excerpted from Across The Fence: The Secret War in Vietnam, SOG Publishing; Second edition (July 11, 2018) , Chapter 14, Reprinted with permission by John Stryker Meyer

Because it was New Year’s Eve, FOB 1 Camp Commander Major William Shelton had ordered extra base security, including having all reconnaissance teams and Hatchet Force personnel on alert in case the local VC or NVA had attack plans up their communist sleeves. Months earlier, a VC had placed a marker on the roof of the lounge, which VC or NVA mortarmen could use as target guide-on. It was also revealed that in the last day or two, one of the Hatchet Force NCOs had found a camp worker carefully counting his steps as he walked away from the clubhouse. That was a common practice for mortarmen or artillerymen to improve their accuracy against a proposed target. As we prepared to ring in the New Year, the jukebox blared, the drinks flowed, the men played the slot machines, and the poker stakes were high. But there was an edge to the evening’s festivities. Shelton ordered it closed early, in case of enemy activity.

Before the club closed, the conversation around our poker table turned to the FOB 4 team that was on the ground in the MA target. Headman told us how happy he was to have been extracted in time to spend New Year’s Eve at FOB 1, instead of across the fence. A few comments were made about how the team in the target area planned to celebrate New Year’s Eve. Someone mentioned that the Americans had taken a bottle of Jim Beam to the field for the occasion. Headman and I gave each other a skeptical look. Personally, I wondered how they could carry a glass bottle and not break it. Another recon man said the two SF troops were unhappy about having to run a target on New Year’s Eve. However, the S 3 brass cut them no slack and sent them out anyway. I knew one of the troops from Training Group and considered him a good recon man. The other I knew only slightly, but there was no reason to believe that either man would be so foolish on the ground.

Around 2200, Spider told us that he and the Covey pilot were going to fly into the team’s AO at midnight to wish the men a “Happy New Year.” While Spider’s O 2 was over the target area, the mortarmen at FOB 1 lit up the sky with flares of various colors and other rudimentary explosive devices, welcoming in the New Year. When he returned to base, Spider told me it sounded as though the Americans had had too much Jim Beam. He gave the team holiday greetings and a reminder that they were in Laos. The only activity we had at FOB 1 was from a poorly trained VC mortar crew who lobbed some mortar rounds at us, but they landed in the ARVN compound to the south instead.

Standing in front of ST Idaho's Team Room at FOB 1, Phu Bai, S. Vietnam, after returning from a recent mission in Laos, from left, Nguyen Van Sau — Vietnamese Team Leader, John Meyer, Nguyen Cong Hiep — ST Idaho Interpreter, and Lynne M. Black Jr., team leader (Photo courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

On 1 January 1969, Spider left FOB 1 early for a commo check with RT Diamondback. He talked to the team’s radio operator and returned to Phu Bai. Later in the morning, however, the One-Two requested a tactical extraction from the AO because there had been a lot of enemy activity around them. While Spider was talking to the SF troop, he heard a burst of AK-47 fire and screams. Then silence. For a long time he was unable to raise anyone on the radio. He knew something was terribly wrong. He finally got an indigenous team member on the radio who said that the Americans were dead, but the indig had survived the attack.

Back at FOB 1, around 1200 hours, someone from the commo shack came into the club and said a Vietnamese team member from RT Diamondback was on the radio, talking to Spider. That was very bad news. Several of the recon team members in FOB 1 headed toward the commo shack. Before we got there, Tony Herrell, a veteran recon man, came around the corner with more bad news.

“They were hit by sappers. It doesn’t look good,” he said. As we tried to walk through S 3 to the commo shack, the S 3 major told the team members to stay outside so the SF commo troops could do their job. The major was universally despised by every recon team member in camp because he showed no sympathy toward any team member and acted as though he didn’t care whether a team lived or died in a target area. The fact that he still had a thick German accent didn’t help matters either. It never occurred to me that perhaps his gruffness was a buffer between having to send teams into targets where the probability of casualties was extremely high and keeping his own sanity.

As always, when a team was in trouble, several team members pulled out their PRC 25s, attached a long antennae, and monitored any radio traffic they could pick up. From FOB 1, SF troops usually would be able to hear the Covey rider talking to the team on the ground. The transmissions from the team on the ground, however, were too far away to be picked up in Phu Bai. The only news this first day of the New Year was bad. We could hear the Covey rider patiently talking to the Vietnamese team members on the ground. They were obviously shaken. At first, we assumed the Vietnamese team members were wounded. But as time passed, it was apparent that the three Vietnamese were alive and had suffered no combat wounds. In addition, there were no NVA casualties.

It appeared the Americans had been slow to react. In a matter of seconds, the sappers killed the three SF troops and chose to leave the South Vietnamese team members alive. The news about the sappers was a triple dose of bad news: First, we had three dead Green Berets. Second, reports One-Zeros had received for months about NVA sappers being a lethal force were now confirmed. Third, by killing only the Americans, the NVA pulled off a major psychological coup. By leaving the Vietnamese team members alive, their survival would plant seeds of doubt and dissension between SF troops and our little people.

That tactic worked momentarily at Phu Bai. Some of the U.S. personnel in camp who didn’t work daily with the little people were openly questioning the loyalty of the Vietnamese team members. I went over to the ST Idaho hootch and told Hiep and Sau to have the team be alert for any untoward comments from U.S. personnel in camp. I also asked them to learn as much as they could about the Vietnamese team members on RT Diamondback as quickly as possible.

Lynne M. Black Jr. and John Meyer out on the range, 1968.(Photo courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

I headed back to the comm center. This time, the major was gone and no one stopped me. The radio room usually took on an eerie silence after a team had been pulled out of a target. That afternoon was no different. The only sounds in the comm center were radio tones, hums and static while the men waited for the helicopters to return to base. And whenever a team was hit as badly as RT Diamondback had been, the comm center took on an additional somberness. On the first day of 1969, it was tomb-like. Three Americans dead, no apparent intelligence other than the fact that all of C&C now knew that the NVA sappers were as good as they had been touted in earlier briefings. For Herrell and me, it was hard to swallow because we had lost a friend. Forever. For several minutes we just sat there, deep in our own thoughts. It had been about 10 minutes since the pilots had called in to report that all of the RT Diamondback team members had been recovered and were returning to Quang Tri.

Oddly, none of the aircraft extracting RT Diamondback received any significant ground fire from the NVA. To me, that was a definite indicator that the NVA wanted to send a psychological message along with the carnage the sappers had wrought on RT Diamondback. On 30 November, we lost seven SF troops and an entire Kingbee crew. Thirty-two days later, we lost three Americans. And since this was a secret war, Walter Cronkite could tell viewers that he no longer believed in the war, but he couldn’t tell the American public about another day in SOG. I stood up and started to walk out of the comm center. A war-weary voice broke the long silence in the comm center with a short, clear transmission: “Happy New Year.”

His words caught me off guard. I thought of those three words in the context of the many close calls ST Idaho had survived since the day I joined it, the same day Sergeant First Class Glen Oliver Lane and an entire ST Idaho team had disappeared in the Prairie Fire AO. I thought of how every member of ST Idaho would probably have been killed in action had it not been for the heroics of Kingbee pilots, Marine and Army helicopter gunship crews and Uncle Sam’s Air Force. On 1 January 1969, the NVA had upped the ante and the thought of going across the fence sent a sobering chill down my spine. I walked over to the club and had my first drink since August. Within days, ST Idaho boarded Kingbees to launch into an MA target in another attempt to find the NVA gasoline pipeline.

And while we headed north to Quang Tri, the 101st Airborne Division choppers carried the six men south. When the choppers landed on the helicopter pad, Colonel Jack Warren had ordered every man in FOB 4 out to the site. He was held in high regard by SF troops because he genuinely cared about his men. It had been said that because of his dedication to the SF mission and the men of SF, that he would never advance beyond the rank of colonel. He had remained in SF too long, a career decision the traditional Army hierarchy despised and punished. Diamondback was from FOB 4, which Warren commanded. At the time, FOB 4 was transitioning into becoming Command and Control North (CCN) as part of a major consolidation of resources within SOG. FOB 1 would join FOB 4 in Da Nang. Where once there had been six FOBs, there would now be three bases, CCN in Da Nang, Command and Control Central (CCC) in Kontum, and Command and Control South (CCS) at Ban Me Thuot.

After the three corpses were unloaded from the helicopter, Warren gave a terse, teary-eyed speech to his captive audience. Warren warned everyone that if they were careless in the field, death was the result of that carelessness. Then he bent down, opened a body bag and picked up a portion of a body of one of the dead Americans. Now he was crying and screaming at his men to never be careless in the field. Warren was never the same after that. Neither was C&C.

During early 1969 FOB 1 was closed. ST Idaho was transferred to CCN at Da Nang, where on occasions the team pulled guard duty atop Marble Mountain. As the team hunkers down for another cold night on the mountain team members enjoy a light moment. From left: Hung, Douglas L. LeTourneau, Cau, Son, Chau, Lynne Maurice Black Jr. and John S. Meyer. (Photo courtesy of Rick Howard)

During January, ST Idaho was moved to CCN at Da Nang and ST Idaho became RT Idaho. Da Nang was two or three times the size of FOB 1. Gone forever was the camaraderie of FOB 1. Additionally, team member Bubba Shore requested to be transferred to headquarters. Bubba and I had run many targets together during his brief tenure on the team. It was a request I respected and granted instantly. Now it was simply Black and myself. Black recruited Do Ti Quang from ST Alabama, a man born in North Vietnam, who moved south with his family to escape communism. We didn’t bring any additional Americans on the team because our Vietnamese team members were so strong and we felt they were better in the jungle than most Americans in camp.

The daily grind of running missions across the fence was wearing on me physically and mentally. As ’69 dawned, I began a mental examination of life in SOG. Being in an elite unit within America’s finest special operations was where I wanted to be. The adrenaline-enhanced high of deadly firefights against a relentless enemy under extremely lopsided odds was intoxicating. I had never experienced such exhilaration or sheer terror. Yet there was a little voice in the back of my head which spoke of survival, surviving not only a vigorous enemy campaign directed against SOG teams, but merely surviving the odds of going home in one piece.

My mind also began the mental debate between rising to the new challenges inherent in a secret war and returning to a safer assignment. My one-year tour of duty was scheduled to end at the end of April. Under the general rules of SOG, after running targets across the fence for six months, I could request a cushy assignment. I had already spent seven months with the team. I was alive, however, thanks to Hiep, Sau, Phuoc, Tuan, and the other men of ST Idaho. I couldn’t just walk away.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966. He completed basic training at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967.

He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. He remained on ST Idaho to the end of his tour of duty in late April, returned to the U.S. and was assigned to E Company in the 10th Special Forces Group at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, until October 1969, when he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970.

He returned to the states, completed his college education at Trenton State College, where he was editor of The Signal school newspaper for two years. In 2021 Meyer and his wife of 26 years, Anna, moved to Tennessee, where he is working on his fourth book on the secret war, continuing to do SOG podcasts working with battle-hardened combat veteran Navy SEAL and master podcaster Jocko Willink.

Visit John’s excellent website sogchronicles.com. His website contains information about all of his books. You can also find all of his SOGCast podcasts and other podcast interviews. In addition, the website includes in stories of MACV-SOG Medal of Honor recipients, MIAs and a collection of videos,

Leave A Comment