9 SOG Recon men vs

10,000-man NVA division

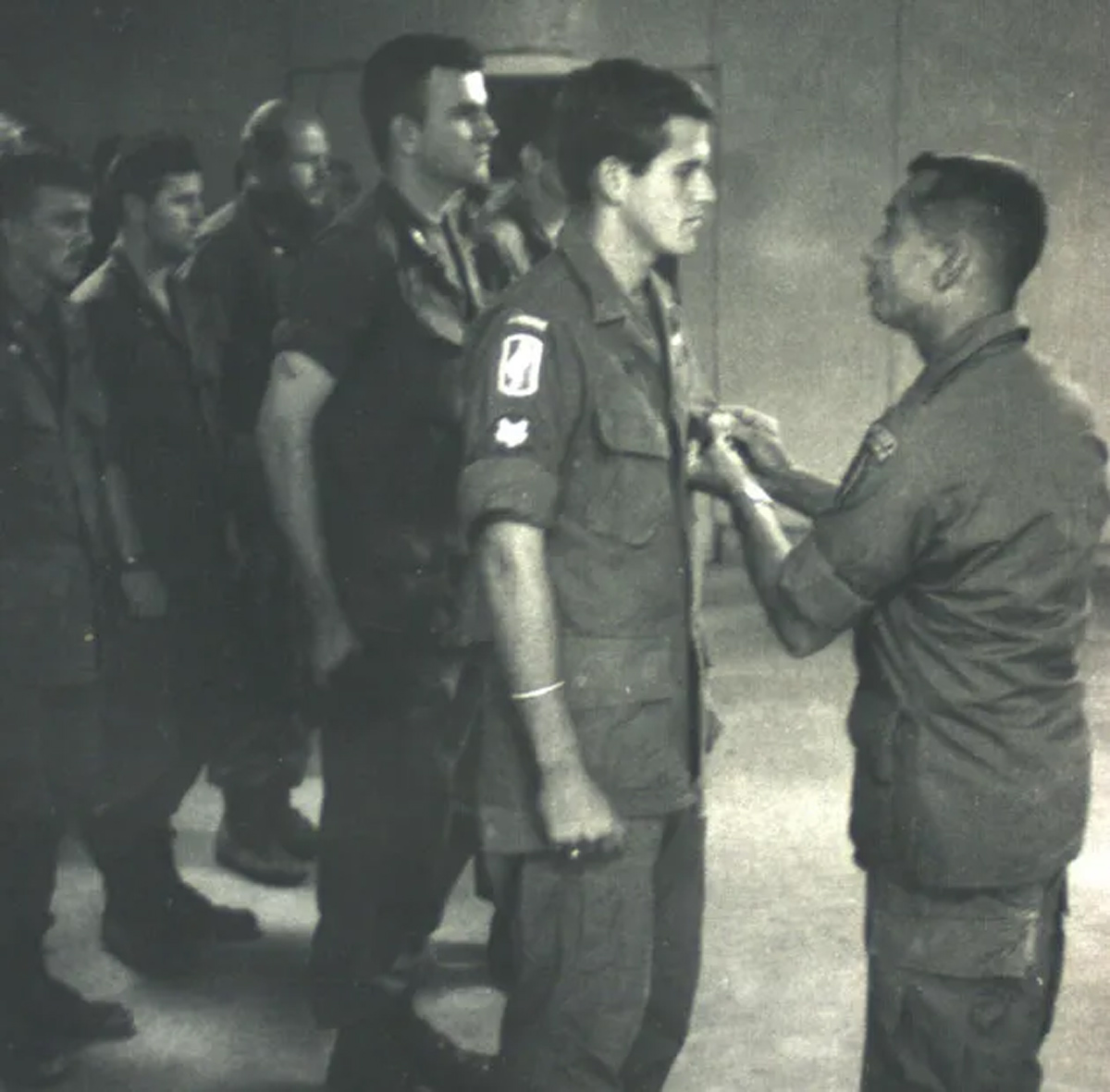

Lynne M. Black, assistant team leader on RT Idaho, is being inspected by Lt. Gen. Richard Stilwell at CCN April 1969. To Black's left is RT Idaho Interpreter, Nguyen Cong Hiep, and to his right is Nguyen Van Sau, Counterpart Team leader.

By John Stryker Meyer

NVA GENERAL TO SOG RECON TEAM: WE SUFFERED 90 PERCENT CASUALTIES

One of the more amazing stories to emerge from the eight-year secret war during the Vietnam War took place on October 5, 1968, west of the A Shau Valley, one of the deadliest targets run by recon teams based at the top secret compound in Phu Bai, FOB 1, run under the aegis of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, or simply SOG.

Earlier in 1968, the communist North Vietnamese Army (NVA) had inflicted severe losses on SOG recon teams running missions in the A Shau Valley and west of it in Laos. That valley was a key location where enemy troops and supplies were funneled down the notorious Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam to take the war into major cities in the northern sector of South Vietnam, Hue, Phu Bai, and Da Nang. Earlier in the war, three Green Beret A Camps were overrun by NVA and Pathet Lao troops. By the fall of 1968, NVA gunners were bringing in more anti-aircraft weaponry and special, highly-trained sapper units were created to hunt down SOG recon teams. The communists offered what amounted to a “Kill An American” medal for any NVA soldier that killed a SOG recon man.

As the weather cleared over the A Shau Valley on Oct. 3, 1968, the brass assigned recon team ST Alabama to run a target just southwest of the A Shau Valley. Specialist Fourth Class Lynne M. Black Jr., a combat-hardened paratrooper who served one year earlier in the war with the 173rd Airborne Brigade was introduced to a new team leader. The sergeant was appointed team leader of ST Alabama only because he had more rank than Black, who had more experience in fighting the NVA than the sergeant. Black was introduced to the new One-Zero and they were ordered to fly a visual reconnaissance (VR) over the target.

VRs were flown as close to the launch date as possible and usually in a small, single-engine observation aircraft flown by two Vietnamese pilots. In this case, the VR was flown two days before the target launch date of October 5, 1968. Black and the new One-Zero (code name for team leader) flew in the rear seat of the small aircraft. The primary and secondary landing zones had been selected when the aircraft was hit by 12.7mm heavy machine gun fire.

Suddenly the cabin was sprayed with blood. A 12.7mm round had ripped through the floor, struck the co-pilot under the chin, hitting with such force that his helmet slammed against the ceiling and ricocheted into Black’s lap — still containing part of the co-pilot’s bloody head.

The pilot slammed the small aircraft down to treetop level and returned to South Vietnam. Black, unable to move or open a window, puked into the helmet. That night, there was a fair share of jokes in camp about Black’s “puke and brain” salad.

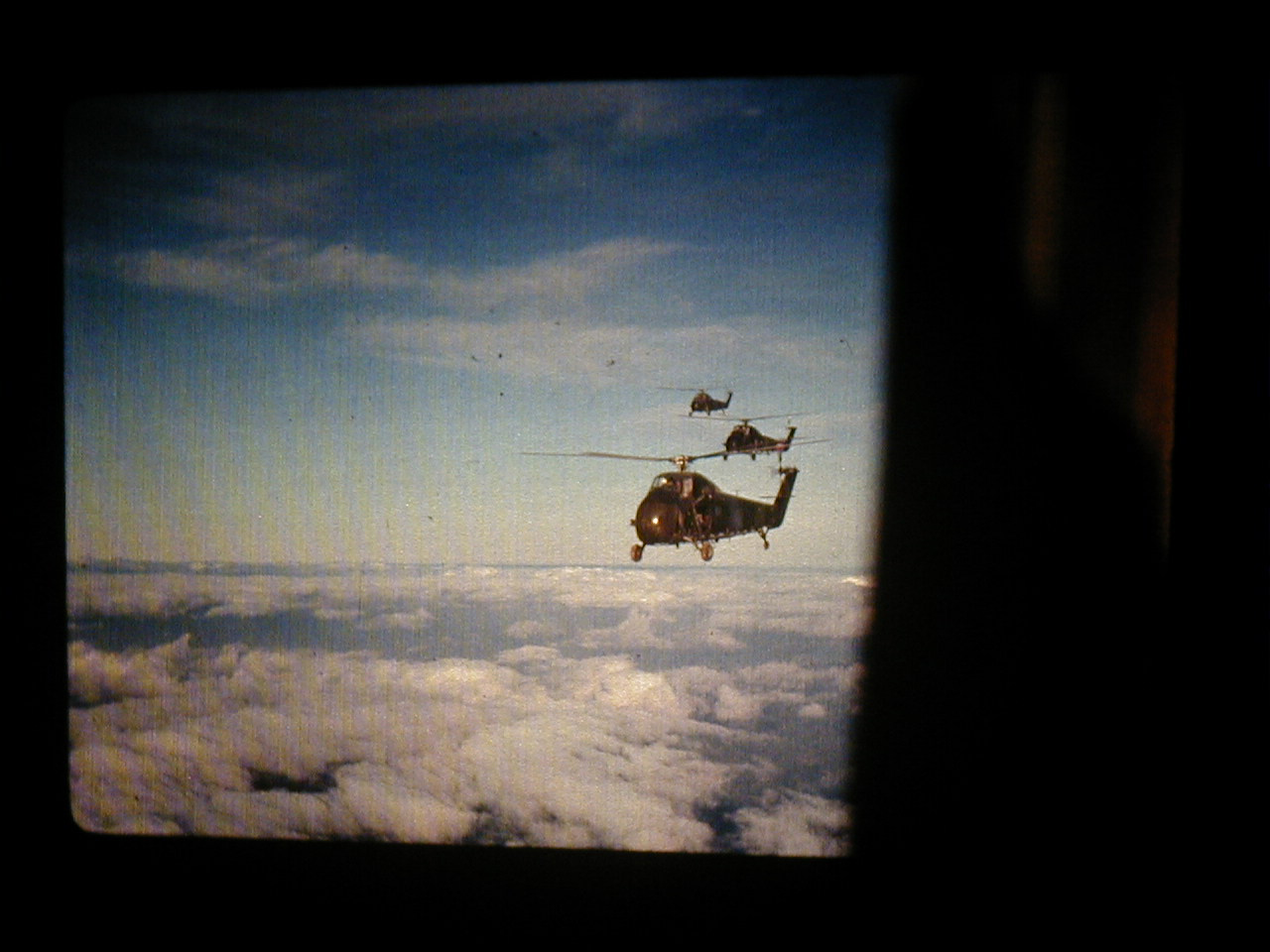

Saturday morning, October 5, there was no laughing when the South Vietnamese-piloted H-34 helicopters (code named Kingbees), flew west across South Vietnam from Phu Bai, near the China Sea, over the A Shau Valley into the target area. The weather was clear in Phu Bai, but cloudy over the AO.

During that flight, Black remembered how the launch commander had said this mission would be a cakewalk. Staff Sgt. Robert J. “Spider” Parks and Staff Sgt. Patrick “Mandolin” Watkins, however, knew that it was a tough target where the NVA had previously run out FOB 1 teams. Additionally, there were no new landing zones for the team insertion. For this target, Watkins was the Covey (code name for Forward Air Controller) rider in the Air Force O-2 Cessna, piloted by Air Force Captain Hartness.

ST Alabama’s insertion started smoothly, as the first Kingbee landed quickly with the One-Zero, One-One (assistant team leader) and three Vietnamese team members quickly exiting the aircraft.

As Black’s Kingbee spiraled downward toward the LZ, he observed an NVA flag planted atop a nearby knoll. From his days in the 173rd Airborne Brigade, Black knew that the presence of an NVA flag meant that there was at least a regiment of NVA soldiers in the area. The knoll was surrounded by jungle. On the west side there was a 1,000-foot drop to the valley floor below.

The numbers didn’t compute for Black – approximately 3,000 NVA against nine ST Alabama men?

Several AK-47s opened fire before the Kingbee’s wheels touched down. Nonetheless, Black and the remaining three Vietnamese ST Alabama team members exited the H-34. As the Kingbee lifted off, the NVA gunfire increased significantly and moments later, the laboring Sikorsky H-34 crashed.

Although this was Black’s first SOG mission into Laos, code named, Prairie Fire, he knew the odds were stacked against ST Alabama. He and the South Vietnamese point man on the team, Cowboy argued vigorously for an immediate extraction. The team had been compromised. The element of surprise was gone. The other American, who had not gone through the Special Forces qualification courses at Ft. Bragg, remained silent.

“No!” said the new One-Zero. “I’m an American. No slant-eyed SOB is going to run me off!” Watkins offered the One-Zero a chance to extract. The offer was declined. The team was to continue.

The team leader then committed a major faux pas: he ordered the point man to walk down a well-traveled trail away from the LZ into the jungle. Black, Cowboy and the point man, Hoa, argued against heading down the trail. The first rule of SOF recon was to never use trails, especially well-traveled ones.

Three camouflaged Sikorsky H-34s from the South Vietnamese Air Force’s 219th Special Operations Squadron flying en route to inserting a team into Laos in October or November, 1968, from FOB 1, the top secret SOG compound in Phu Bai. At least two were shot down Oct. 5, 1968 flying in support of ST Alabama. (Photo courtesy of Jerry Herman)

WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE

The One-Zero pulled rank and ordered the team to move down the trail, with Hoa leading the way and the elder Green Beret following a short distance behind him. The trail wound into the jungle, and curved to the left. ST Alabama moved cautiously. As the team went down the trail, it moved parallel to a small rise on its right that was about 10 to 20 feet above the team. On it, an NVA colonel had quickly assembled a force of 50 NVA soldiers, who set up a classic L-shaped ambush.

The quiet of the early morning jungle was shattered when the NVA troops opened fire with their AK-47s and SKS rifles.

The AK rounds ripped into the point man’s chest and face. The fatal impact of those rounds lifted the canteen covers around his waist, appearing to keep his body suspended in air. What had been a human body milliseconds earlier was being chewed into an amorphous form that hit the ground with a sickening thud. Arterial blood spurted high into the air.

Three rounds slammed into the One-Zero’s head, blowing off the right side of his face, killing him instantly. The One-One, a gutless son of a general, buried his face in the dirt and started praying.

Black and the remaining ST Alabama team members returned fire. The Green Beret stood there, firing on single shot, picking off NVA soldiers on top of the rise. He reloaded his CAR-15 and went down the line, shooting them one after another. Sometimes they spun and he shot them a second or third time.

As the NVA continued to fire on the team, Black and Cowboy formed the team into a circle and directed a barrage of M-79 grenade rounds and CAR-15 fire into the surrounding jungle.

Then startlingly, eerie silence. Black thought he was in his grave. ST Alabama was in a low spot with the ground rising 10 to 20 feet on both the left and right.

Both the NVA and ST Alabama tended to their wounded while the living combatants slammed loaded magazines into their hot weapons. There was moaning and groaning, human suffering on both sides. Black got on the PRC-25 FM radio to tell Covey about ST Alabama’s tragic turn of events. Black and Tho scavenged weapons and ammo from the dead ST Alabama team members.

Fortunately, Covey was still airborne. Black reported that he had two KIAs and two WIAs and was surrounded by NVA troops.

Covey responded, “You’re not a doctor, nor for that fact, a medic. You can’t determine who’s dead or alive! Bring out all bodies for verification of death.”

Their argument was drowned out when more than 100 NVA regulars opened fire on ST Alabama, as enemy troops had reinforced the initial ambush unit. By now, the NVA were two rows deep: the front row fired AK-47s, the second row threw grenades or fired B-40 RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades).

Another Vietnamese ST Alabama team member was wounded. The team had to get out of the hole or die in it.

The bold NVA told the ST Alabama members to “Chieu hoi,” or “surrender,” speaking first in French, English and finally, Vietnamese. ST Alabama’s weapons drowned out further Chieu Hoi requests. The One-One continued to pray. Black couldn’t believe it.

At center, Khanh “Cowboy” Doan with Jocko Willink, left, and John Stryker Meyer, right, after recording Jocko Podcast # 258 on November 17, 2020 (courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

“This is no time to pray…do unto others before they do unto you!” he yelled. Whether or not the NVA soldiers were praying, they continued to move around ST Alabama, some climbing into the trees. Cowboy and Black crawled 15 feet toward them, close enough so that Cowboy heard the NVA commander tell his troops to prepare to charge ST Alabama’s position. The commander also told his troops on the long side of the “L” ambush not to fire. Black quickly rigged a claymore mine in the direction of the pending charge.

The fearless NVA mounted a charge toward ST Alabama with AK-47s on full automatic. Black detonated the claymore mine. It blew a huge hole in the NVA ranks.

Before the smoke cleared, ST Alabama ran through the human carnage, firing CAR-15s on full automatic and throwing M-26 frag grenades while dragging their three, wounded team members. Miraculously, ST Alabama made it through the NVA wave of attackers and moved back toward the LZ, leaving their dead behind.

Covey had bad news for Black: the Kingbees had to return to Phu Bai to refuel. No extraction was possible for at least two to three hours. Meanwhile, the relentless and bloodied NVA ran after the spike team. Black planted a claymore mine with a five-second time-delay fuse. It wreaked havoc on the hard-charging NVA.

As the smoke cleared and the body parts settled back to earth, ST Alabama split in half and again charged through the battered and torn ranks of the NVA warriors, killing any standing enemy. They counted at least 50 NVA dead.

Again, eerie silence engulfed the team and ST Alabama regrouped. Just as suddenly, a new wave of NVA soldiers rushed the beleaguered team. ST Alabama had been pushed near the cliff. It was a thousand feet to the ground if they went over the edge. Now on line, ST Alabama charged through the weakest NVA flank, killing several more enemy soldiers.

As he moved out, something hit Black on the side of his head, knocking him to his knees. He was scrambling to get up when the grenade went off. The last thing he remembered was being slammed into a tree, face first, and his CAR-15 carrying handle digging into his chest.

He thought he was drowning, but then he felt feet kicking him and hands slapping him all over. It was the team. They were beating Black back into consciousness and pouring water on his face. He tried to get up, but his legs didn’t work. From the knees down, there were no fatigue pants, just surface bleeding. One of the guys started smearing gelatinized rice on the injured One-Two’s (code name for radio operator) legs, arms and chest. Black’s web gear and what was left of his fatigue jacket were lying shredded, bloody on the ground. The CAR-15 was bent where the barrel meets the receiver and the bolt couldn’t be pulled back. One of the team buried it.

By 0900 hours, word of ST Alabama’s precarious position had spread through FOB 1 like wildfire. Requests were made for extra assets. It was now an official Prairie Fire Emergency. All aircraft were pulled from their missions and sorties to support ST Alabama. Any gunships attached to SOG were summoned to their aid.

The first gunships to arrive were the Marine Hueys known as Scarface, from HML-367 based in Phu Bai and Da Nang in 1968. With them was a CH-46 with a ladder attached for jungle extractions. When the twin-rotor helicopter entered the AO, it was hammered by heavy enemy ground fire, as were the Marine gunships. Green tracers were seen going toward the CH-46. The ground fire became too intense and the Marine chopper had to withdraw and make an emergency landing at Camp Eagle in the 101st Airborne Division Compound. Despite the hits, Scarface gunships made several passes, expending all ordnance, before returning to base to reload.

Kingbee officers regrouped and prepared to fly back to Laos to extract what was left of ST Alabama. S-3 asked for volunteers for a Bright Light mission and every recon man in FOB 1 volunteered. ST Idaho was scheduled to insert into the Prairie Fire AO the next day, October 6. Because the team was ready to go, there was some initial discussion about Idaho being the Bright Light team. As the day dragged on, however, and the perilous nature of ST Alabama’s situation worsened, the Bright Light option faded because the original LZ was now too deadly for any helicopter to attempt an extraction.

When Watkins returned to FOB 1 for the Cessna to refuel, he told the others that it didn’t look good. He wasn’t sure if they’d be able to get them out. He explained the low, sunken area in the LZ, the spotty weather and how smoke from expended ordnance hung over the LZ, making it more difficult to spot the team and to deliver air strikes accurately.

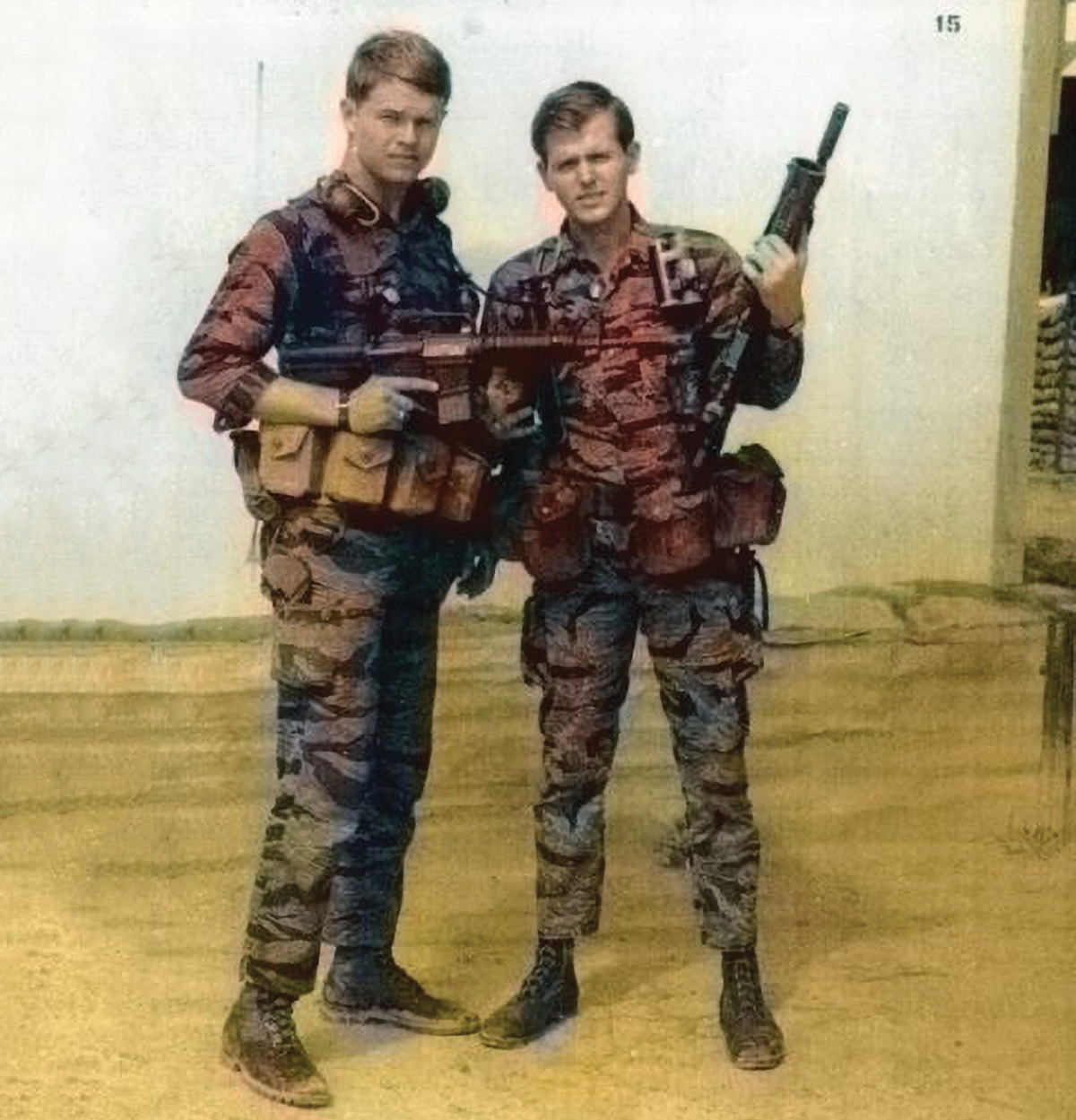

Black with his CAR-15 and attached XM-148.

TEAM RESUPPLY READIED

A resupply of ammo, grenades, claymore mines, M-79 rounds, water, bandages and morphine was placed on a Kingbee and launched toward ST Alabama.

In Laos, Cowboy worked on Black’s legs. He told Black the last wave of NVA had continued onto the LZ. Cowboy and Black heard more U.S. Marine Huey gunships arrive overhead and witnessed the NVA on the LZ open fire, hammering the lead aircraft.

Again the One-One panicked, cried and shouted skyward. The Vietnamese team members, speaking through Cowboy, told Black that they were going to kill the One-One if he didn’t shut up. Black agreed.

“I’ll pull the trigger on him, myself.”

“God forgive you!” the One-One responded tearfully.

“You and your God have no place here!” Black retorted. Cowboy grabbed a startled Black by the throat and lifted a Catholic crucifix from his neck and shoved it to his lips.

“It’s the gods who have allowed us to get this far, Round Eyes!” he whispered tersely through clinched teeth.

The sound of approaching Kingbees ended the religious debate as the realities of surviving an A Shau hell became center focus. The able-bodied picked up the wounded and moved toward the LZ. Spider, the Covey rider at this time, told Black that the first Kingbee was enroute to the LZ, but they planned to work the area surrounding ST Alabama with tactical air support first. In this case, a F-4 Phantom jet pilot told Black to “key your handset for 10 seconds. Put your heads in the dirt, over.”

Black acknowledged his radio transmission and told his teammates to put their heads down. As he looked into the sun, he observed the slowest moving full-flapped Phantom he had ever seen. The glide path ratio was critical. Seconds later he saw the tree line across the LZ explode into sheets of white, yellow and orange flames, setting the jungle on fire with napalm. The ship banked sharply, appearing to stand its wing tip on the ground. The pilot cranked on the burners, dropped down into the valley below and then began a vertical climb.

NVA small arms opened up on all sides of the valley. The F-4 took numerous hits on its armor-plated underbelly. Among those shooting at the fast mover were several NVA troops about 20 feet from ST Alabama’s perimeter. As the napalm torched the jungle, dozens of NVA soldiers scurried into the open field to escape the instant inferno that had engulfed their comrades.

As a second jet rolled in for a gun run, the NVA initiated what they called “getting close to the belt.” In this case, the NVA soldiers moved toward or outright charged ST Alabama to get as close to the team members as possible to avoid being hammered or burnt by Air Force, Marine or Army air ordnance.

Firing on single shot, ST Alabama picked off each of them as they came out of the burning jungle. The Phantoms returned with two cannon and minigun runs along the team’s perimeter. Before the dust settled, the Vietnamese team leader, Tho, and Cowboy crawled out and recovered several AK-47s and precious ammunition from the dead enemy soldiers, as their CAR-15 ammo was dwindling to a few precious rounds.

Two of the 9-cylinder Kingbees came chugging up the valley toward ST Alabama. Black popped a green smoke marker. The NVA popped an identical smoke marker, confusing the pilots with devastating results.

Lynne M. Black Jr. riding in a South Vietnamese Air Force’s 219th Special Operation Squadron H-34 in late November 1968, en route to a target in Laos. Talking on the radio is SOG team leader Tim Schaaf. Photo courtesy of John E. Peters

DEADLY CONFUSION ON THE LZ

The first Kingbee followed the NVA’s smoke marker, and took a direct hit from a rocket, which toppled it on its side, smashing each rotor blade into the ground. The approaching ST Alabama team members narrowly missed getting hit with shrapnel from the crash.

Black, Cowboy and another team member charged the rocket position, killing three NVA before a hail of NVA fire drove them back to the team perimeter. The second H-34 hit an outcropping of rock on the western side of the knoll after taking heavy enemy gunfire. It exploded and fell 1,000 feet to the valley floor below, taking with it ST Alabama’s resupply.

Covey barked, “Nice going, Blackjack!”

“Fuck you, Covey,” he replied. Cowboy told the One-One to pray for everyone except Black because he was on the “devil’s side.” Black broke into laughter as he assessed ST Alabama’s predicament: ammo was desperately low; the blood trails looked like slug slime, the F-4 Phantoms had expended their ordnance and Covey was belligerent. His nerves were shot. Training and man’s basic survival instinct had completely taken over. Then the NVA bugles sounded.

Waves of NVA troops carrying SKSs with fixed bayonets advanced on ST Alabama. When they were 15 feet away ST Alabama opened fire. The semi-automatic SKSs were no match for the fully automatic firepower of the spike team. After the first burst of full automatic fire, the team went to single shot. It was another turkey shoot. Without a word, a look or a plan, acting solely on instinct, all of them, except the One-One, scurried forward and dragged back dead NVA soldiers, placing the bodies in a circle around them and stacking them high.

The deadly skirmishing continued for several hours before Covey told Black that more gunships and five Jolly Green Giants, the heavily armored Sikorsky HH-3Es, were en route.

“Blackjack, Covey. What you’re up against is the regiment you were sent to find, over.”

“Is that all, only 3,000 of the bastards? Well, I think we made a dent in ‘em. Who’s winning?”

“They are,” Covey responded. As Black finished his commo, he saw a sight he would never forget. The NVA formed a front line of NVA troops who were firing their AK-47s. Behind them were several NVA soldiers swinging thongs made of leather and cloth, which held three to five hand grenades each, and with a jerk of their collective wrists, the NVA hurlers launched more than two dozen communist-manufactured grenades at ST Alabama.

The sky was full of grenades. Fortunately, they weren’t U.S. grenades. They hit the ground and threw dirt, smoke and dust all over the place. ST Alabama looked up just as the AKs started again, and behind them, the thongs whirling overhead like helicopter blades. When the AKs stopped, the grenades were released. ST Alabama fired. More grenades were released; Alabama threw some back.

ST Alabama was caught in a deadly version of the kid game “Pop Goes the Weasel.” The AK-47s continued to roar. Alabama ducked. The grenades were launched. Alabama rocked. Catch, throw, duck, rock. Catch, throw, duck, rock!

The NVA advanced. Grenade shrapnel severed the antenna on the PRC-25 portable radio Black carried. He quickly rigged an impromptu antenna from wire. The relentless NVA continued to advance, inch by bloody inch.

Cowboy took two Vietnamese team members over the cadaver-walled perimeter, seeking to get another line of fire to direct at the advancing NVA. The advance continued, despite firing from Black and the remaining Vietnamese team members. The NVA were now merely feet away from the team’s perimeter.

At the last moment, with the NVA a few body lengths away from the perimeter, two Huey gunships from the Americal Division, 176th Aviation Company, the Minute Men Muskets of 36-C, arrived. The UH-1B pilots were code-named “The Judge” and “The Executioner.” They roared into the battle, first with a minigun blast, followed seconds later with several 2.75 inch rockets placed in the NVA ranks. Alabama was saved, if only for a little while. The NVA backed off for a few moments, briefly licking their collective wounds, although they were far from whipped. New assault lines of NVA troops formed. Before the NVA opened fire on ST Alabama, however, the Executioner confronted the NVA head on. With both door gunners blazing away with their hand-held M-60 machine guns, he hovered inches off of the ground, between the team and the front of the NVA, and skipped several 2.75 inch rockets off the ground into the NVA. Before the bleeding, startled NVA could respond, the pilot lifted the old UH-1B model gunship over the tree line and ducked down into the canyon, regaining enough air speed to return for another pass at the ST Alabama perimeter.

Lynne and I at Phu Bai FOB, 1 December '68.

THE BATTLE CONTINUES.

Before ST Alabama could celebrate, the NVA charged again. Three more dead NVA were added to the cadaver wall.

Silence dominated the battlefield. No bird chirps, no speaking, no noise of any type. Even the aircraft over the scene had flown far enough away that their absence amplified the empty air. The One-One, who hadn’t fired a single shot, continued to pray.

Black patched up a bleeding Cowboy. He gave some him morphine before bandaging a wound on his right side from an AK-47 bullet wound.

“Where’s John Wayne when you need him?” Cowboy asked. The others laughed.

“Chieu Hoi, du maa (Give up, motherfuckers)!” an enemy soldier yelled. Another NVA told Black to “Chieu Hoi” in English. Black flipped him the bird as a sniper shot Alabama’s tail gunner, Cuong, in the crotch, hitting an artery.

As Tho applied direct pressure to Cuong’s wound, an A-1H Skyraider lumbered into the AO. Flown by a pilot code-named “Snoopy,” he roared in from Black’s left, brushing the treetops, full flaps, working his throttle. The aircraft was so close to the team that Black could hear the distinctive, metallic click-click of the napalm canisters being released from the old Korean War era plane. The Skyraider appeared to be falling, but actually it slipped down into the valley to escape NVA gunfire, as the Americal UH-1B Muskets’ gunships and fast movers had maneuvered earlier in the day.

His wingman appeared and as he flew over the team they could hear the nuts and bolts and God knows what creaking and groaning as he salvoed the rockets. The NVA were pissed. Again, the hot shell casings from the airborne warships rained down on ST Alabama.

Then three small mortars opened fire. Black knew there was no way in hell any of the team could catch mortars and throw them back. He and the Vietnamese team leader, Tho, rolled over the cadaver wall toward the mortars, cautiously picking their way through the charred NVA bodies and carnage from the previous airborne assaults. They moved into the jungle, within 20 feet of the first mortar tube. Tho drew a plan in the ground. He would hit tube one, Black would hit tube three and they’d combine on tube two.

After the mortarmen launched three salvos, Tho opened fire on his target while Black attacked his targeted tube and several nearby NVA soldiers.

The survivors chased Black. In the confusion, the NVA opened fire on each other as Black headed toward tube one – with NVA soldiers still chasing him – where Tho was pinned down. Black threw a hand grenade and killed at least three NVA with a blast of gunfire to free Tho. They turned on the NVA chasing Black and dealt with them. Then he and Tho wiped out the NVA at the second tube before they quickly returned to the team, all the while picking up ammo and loaded AK-47 magazines from dead or wounded NVA soldiers.

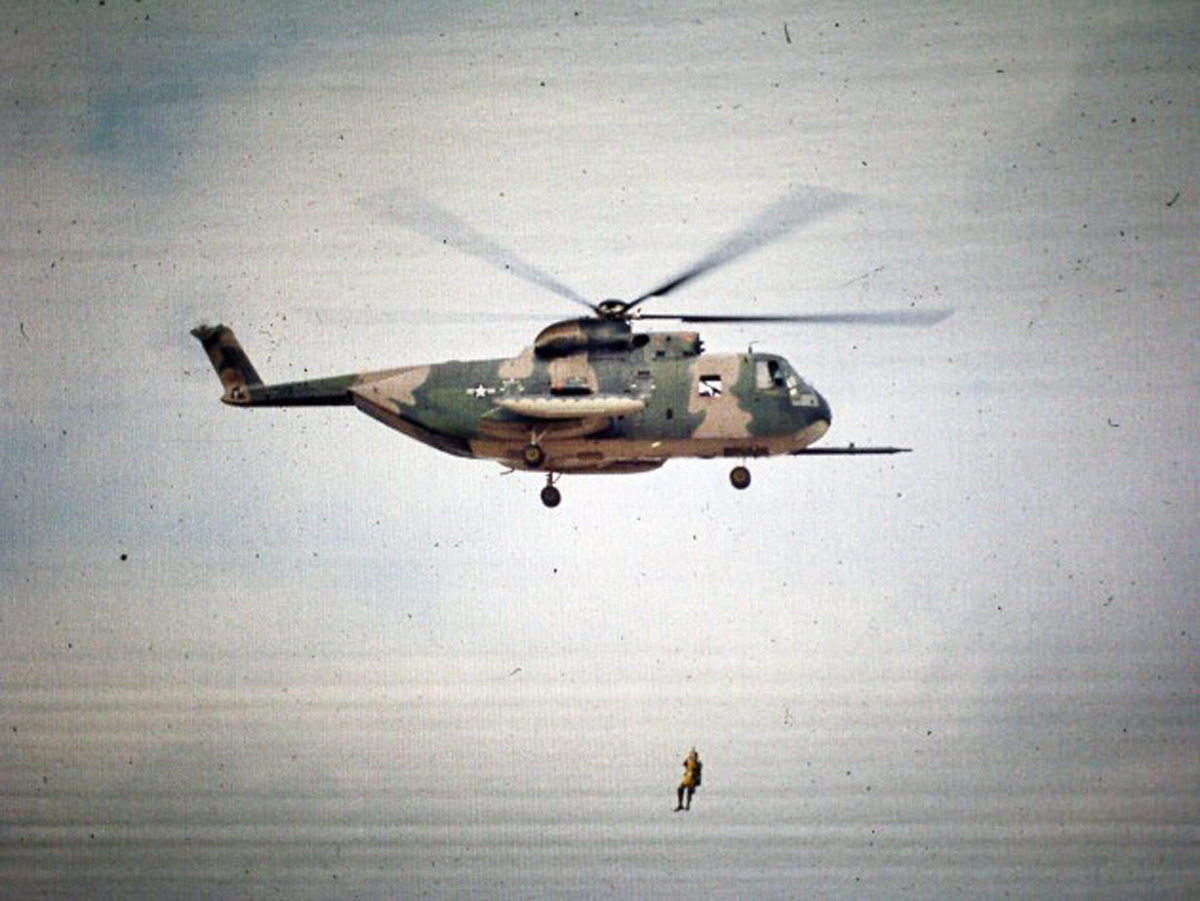

By now, Watkins had returned to flying Covey rider above ST Alabama. Spider had called the U.S. Air Force’s 37th Air Rescue and Recovery Group in Da Nang to attempt a rescue of ST Alabama. During the Vietnam War, when pilots were shot down in North Vietnam or Laos, and all else failed, the Jolly Green Giants of the 37th Air Rescue and Recovery Group were called. The Sikorsky HH-3E weighed 22,050 pounds loaded, had two General Electric T58-GE-5 turboshaft 1,500-hp engines, extra armament and firepower, and they were manned by remarkable Air Force pilots and crews.

The first heavily armored Jolly Green Giant HH-3E, code-named JG 28, started its descent to the LZ from 4,000 feet. As it approached, the JG 28 crew was looking for an orange panel on the southeast side of the LZ. However, as the aircraft was about to touch down, crewmembers noticed a second panel. The NVA had an identical panel. The momentary pause was nearly fatal for JG 28, as the NVA opened fire on it from several sides. The heavy gunfire severed the main fuel line, causing a massive fuel leak inside the HH-3E.

JG 28 had to withdraw from the LZ. In a matter of seconds, there were two to three inches of aviation fuel on the aircraft’s cabin floor. The fumes temporarily blinded the crewmembers. The pilot was able to stabilize the rugged HH-3E and returned to Da Nang, escorted by SPAD 11.

As JG 10 hovered a safe distance away from the LZ, Watkins directed a few more air strikes around ST Alabama, with the hope that the communist soldiers would put their heads down long enough to get the team out.

After a few air strikes, JG 10, piloted by Air Force Major Vernon R. “Sam” Granier, was called to attempt the extraction. For Granier, this was his first assignment in the Prairie Fire AO as a Jolly Green Giant pilot.

Aviators from the Americal Division, 176th Aviation Company, the Minute Men Muskets of 36-C who were attached to SOG missions and based out of FOB 1 at Phu Bai. From left: William “Berg” Garlow, door gunner (the Oct. 5, 1968 mission with ST Alabama was his first into Laos), pilots Jerry Herman, Mike “The Judge” Arline, and Dan “The Executioner” Cook. This unit was a part of the air armada that flew in support of ST Alabama that day and numerous other SOG mission during the Vietnam War. (Courtesy Jerry Herman)

When the call from Covey came, Granier knew that there were two U.S. Green Berets on the ground with their Vietnamese team members and that the majority of the team was wounded. He didn’t hesitate. Granier piloted the Jolly Green Giant toward the LZ. Unlike JG 28, Granier knew which side of the LZ ST Alabama was on. As he approached the LZ, NVA gunfire again reached a deafening roar, despite ST Alabama directing firepower at the communist soldiers.

As Granier began to hover over the LZ, JG 10 was hammered by enemy gunfire. His crew chief reported that one NVA round had torn a six-inch hole through the floor. The round apparently slammed into one of the engines. Both engine-warning lights went on. Both engines were on fire.

Granier did a 180-degree turn and moved the damaged aircraft away from the deadly enemy fire, away from the team, struggling to keep it airborne, calling upon all of the training he had received to continue flying. Both crewmembers continued firing their machine guns as Granier battled to keep the ship in the air.

Time ran out for JG 10. After traveling several hundred yards, Granier warned his crew to brace themselves for a crash landing. Both crewmembers continued firing their weapons until the burning HH-3E slammed into the jungle.

ST Alabama was stunned. Covey and all of the men flying over the target area viewed the horror in grim silence.

The men back at FOB 1 monitored the radio transmissions on their PRC-25s FM radioes as Covey talked to Black. Spike Team Alabama’s radio signal was too weak to hear any response. The word spread through camp about the latest horrific turn of events surrounding ST Alabama. The usual hustle/bustle of a Saturday at FOB 1 was replaced by quiet, hushed tones as the entire compound feared the worst, but continued to pray for the men of ST Alabama. Word of a proposed Arc Light mission reinforced the gravity of ST Alabama’s situation. An Arc Light was a strike by a B-52 bomber from more than 25,000 feet.

Back in Laos, the stunned members of ST Alabama returned to their cadaver perimeter once again, nearly out of ammo. One-One was face down, muttering, “The Lord is my shepherd…” One of the Vietnamese went about collecting AK-47s and ammo from the dead NVA as Spider and Watkins directed more air strikes around the team.

Within 10 to 15 minutes after Granier’s burning HH-3E crashed into the jungle, Covey learned that there were two survivors from the Jolly Green Giant and asked ST Alabama if they could locate the remaining crewmembers. Granier had broken his back, but somehow had pulled himself from the burning HH-3E. The other Jolly Green Giant survivor, Sergeant Earnest Dean Casbeer, had been thrown clear of the crash. Neither knew the location of the other.

Watkins told Black where the Air Force survivors were and that they’d run a daisy chain between his position and the men, hopefully to clear the area enough for the team to get to both of the survivors.

The NVA threw one more curve at ST Alabama. When Black tried to talk to Covey, he found the primary, secondary and alternate FM frequencies jammed by the NVA. Frustrated, Black smashed the PRC-25 and pulled out his URC-10 ultra-high frequency survival radio. He was told that an Arc Light strike was being planned for this area as soon as possible.

By now all the air assets, Navy, Marine and Air Force, which had been scheduled to fly sorties into North Vietnam, were diverted to the Prairie Fire Emergency surrounding ST Alabama.

Covey directed numerous air strikes, including more gun and rocket runs from helicopter gunships. Scarface, the Hueys from the Marine Light Helicopter Squadron 367, returned to make several runs. After refueling and reloading in Phu Bai, the Minute Men Muskets returned to wreak havoc on the persistent NVA troops. They pounded the jungle area between ST Alabama and the Air Force survivors as part of the daisy chain tactic.

Jolly Green Giant of the 37th Air Rescue and Recovery Group. (Courtesy Jerry Herman)

JOLLY GREEN GIANT HOVERS IN JUNGLE

Around 1800 hours, a Jolly Green pilot, Air Force Major Don Olsen, called over the radio, “Blackjack, JG 32, over. I’m parked down in the draw, in the trees from you. You have 20 minutes of fuel before I leave…the first person we MUST see is an American…Hurry! We’re taking heavy ground fire.”

Anything that couldn’t be carried was thrown over the side of the cliff. As quickly as the wounded could move, they headed toward the Jolly Green Giant. The chopper had literally cut away treetops and branches to nestle into the thick dark green foliage, thus reducing its profile to enemy gunners. Olsen had to keep the aircraft stable as there were large trees on all sides of the aircraft. The trees were large enough that they could severely damage the five rotor blades and cause the chopper to crash if he hit any of them.

Covey directed more air strikes in a daisy chain fashion in the portion of the jungle between ST Alabama and the hovering Jolly Green Giant. Watkins hoped this would drive out or kill the NVA in the zone. Even that task became more difficult, as smoke from all of the expended ordnance continued to hang above the trees, decreasing the visibility for pilots and helicopter gunners.

As they moved toward the hovering HH-3E, ST Alabama entered a cool ravine before climbing the final hill to the chopper. There they encountered a village with hooches built on 10-foot stilts, complete with large pots cooking rice and vegetables. Instead of NVA troops, Black found an American taking food from one of the pots. He was the Flight Engineer, Sergeant Earnest Dean Casbeer, one of the two Air Force survivors from the crashed HH-3E. Soon they found Granier.

The NVA focused heavily on the chopper, easing the pressure on ST Alabama. As the beleaguered recon team neared the Jolly Green, Black thought it felt like they were moving closer to the gates of hell itself. The NVA were pouring small arms fire and RPGs at the hovering ship while the door gunners and pilots intermittently fired the mini-gun, M-79s and M-60s, while helicopter gunships and Skyraiders made gun runs around it.

Time was against them. The weather began to close in. The smoke from previous air strikes hung over the area for longer and longer periods of time before clearing enough for the next attack from the air.

On the ground, the men of ST Alabama heard NVA running through the bushes around them. Fortunately the NVA failed to spot the spike team or the Air Force crewmen. Desperate, Black had to move his team onto a trail so it could move to the hovering HH-3E more quickly. As the team moved up the trail, the tail gunner was shaking violently and had turned a pasty white. Team members set Cuong down and proceeded to the aircraft. At the crest of the trail, they saw the HH-3E taking hits and dealing out its own; its M-60 was red hot. Black saw someone firing an M-16 out of one of the windows.

As Black moved to the chopper, the intensity of gunfire seemed to multiply. The air was so full of lead he could see it. Fuel and bits of metal skin fell from the aircraft as they reached its underside.

The jungle penetrator smashed to the ground next to him and raised three feet before he put three team members on the first load. Granier, the Air Force Flight Engineer and a wounded ST Alabama team member were on the second hoist lift. The wounded Vietnamese became entangled in jungle vines while he was being hoisted upwards. The Air Force hoist operator had to stop the hoist, lower it and give him time to untangle himself. When the hoist moved up toward the aircraft, the Vietnamese was not sitting in the seat, but hanging on, with assistance from Air Force Sergeant Casbeer.

Despite the NVA gunfire, Black ran back to the bamboo thicket where he had left the remainder of the team. Cuong, the dying tail gunner, pointed his .45 cal. pistol at the advancing NVA and said, “Toi kiet (I die).” He motioned Black to return to the HH-3E before shooting himself.

Black was running back to the ship when two NVA stepped onto the trail and pointed their AK-47s at him.

“Chieu hoi!” one of the soldiers shouted. Black stretched out his arms and continued walking toward them.

When he was only a few feet away, he said, “Chieu hoi!” The young NVA soldiers appeared surprised. Before they could react, Black grabbed the AK-47s by their searing barrels and stripped them from the soldiers. He backhanded the soldier on his right and smashed the other soldier in the face with one of the weapons.

He left the stunned soldiers lying there as he sprinted to the chopper, where he found the praying One-One. The rest of the team was on board, firing any weapon they could get their hands on. As the jungle penetrator lifted Black and the One-One upward, they were showered with hot spent casings from the M-60 and other weapons being fired from inside the aircraft.

The entire team fired out the windows and from the back door as the overloaded HH-3E began to lift out of the jungle. Major Olsen told Covey he was at maximum power.

ST Alabama photo a week after the mission.(Courtesy John Stryker Meyer)

ROCKETS SLAM INTO CHOPPER

As the Jolly Green Giant slowly rose, Black felt the ship making upward surges from the B-40 rockets slamming into the armor-plated underside of the aircraft. It felt like a giant slugging the ship in the stomach, boosting it upward with each rocket blast. From his view above the fray, Watkins couldn’t believe the bird kept flying. Somehow the pilot got the Jolly Green out of there.

Once clear of the jungle hole, the ship began its ascent out of the valley and the shadow of death. The door gunner removed his helmet and placed it on Black’s head. The pilot told him, “We’re on our way home.” Not quite.

From above, Watkins saw the crippled ship catch fire and try to make it out of the killing zone. It crossed two ridgelines before descending into a clearing where it crash-landed. Olsen had gotten them out of the killing zone, but JG 32 had flown its last rescue mission. Everyone except Black and the One-One were transferred to another Jolly Green Giant, piloted by a Coast Guard exchange pilot, Lieutenant Commander Lonnie Mixon. Mixon took over 30 hits picking up ST Alabama and the Air Force survivors.

A Cobra gunship landed and opened the armament compartment doors, which had seatbelts attached to them. Black and the One-One buckled up and were soon airborne alongside the Jolly Green Giant, returning to Da Nang. They were flying so fast that Black had to turn his bloodstained face away in order to breathe. Within minutes, he was so cold he was shivering uncontrollably. The Cobra landed at a Marine medevac site, where the Americans were wrapped in poncho liners and helicoptered to Da Nang.

After Watkins knew that Black, the remaining personnel from ST Alabama, and the Air Force survivors from JG 10 were cleared from the original target area, they hammered it with everything they had, including more napalm, bombs and gun runs. Captain Hartness, the pilot of Watkin’s FAC plane, was so mad that he flew the 0-2 down into small arms fire range and fired 2.75 inch rockets into the area where the NVA had knocked down JG 10. He and Watkins took a hit to the front and the engine died. Hartness somehow got the Skymaster 0-2 up, out of the area and back to Phu Bai. There was no engine pressure when he landed.

Meanwhile, back at the Da Nang infirmary, everyone was getting patched up. When Tho saw Black, he raised his right hand in a fist above his head.

“CHIEU HOI, DU MAA!” he yelled. The One-One, who was not wounded, stood up on a chair.

“Listen up, men! I want to commend each and every one of you for a job well done. As the team leader of ST Alabama, I want you to know I personally am going to put each of you in for the Medal of Honor. You medics take care of my people.” He stepped down and left the room. The wounded, exhausted members of ST Alabama looked at Black, aghast.

Black couldn’t believe what he had heard the One-One say, but because Alabama was his team and since they were in another unit’s facility, he wouldn’t do anything that would reflect poorly on the entire team. That night, Black was so mad he knocked the pills out of the medic’s hand and instead of lying down for treatment, he went with a Jolly Green medic to his Air Force barracks for a show. There, the medic applied bandages and compresses to the numerous bleeding abrasions and shrapnel holes in his chest, back, arms and legs, and to the burns on his hands from the AK-47s.

“SO THAT OTHERS MAY LIVE”

While walking to the club, they passed a line of parked Jolly Greens. “So That Others May Live” was printed on the side of one HH-3E. Indeed, two members of the U.S. Air Force’s 3rd Air Rescue and Recovery Group in Da Nang had paid the ultimate price while attempting to extract ST Alabama from Laos. That Air Force slogan had a profound impact on Black, the ST Alabama survivors were alive thanks to the Jolly Green Giants and the heavy price their men paid that day. Not far from Black, HH-3E pilot Granier was being treated for his broken back.

When they entered the club, every man present rose and started clapping. Everyone crowded in and started shaking hands and slapping Black on the back. The pain was excruciating, but Black thought about how a few hours earlier when ST Alabama was fighting for its life. Now he was in a club with men lined up to buy him drinks. The pain was bearable.

The clock said 2200 hours. At Phu Bai, a subdued gathering in the club celebrated ST Alabama’s survival and quietly chalked up the deaths of several good Vietnamese team members to poor leadership. Little was said about the arrogant, dead One-Zero. Recon members talked to Watkins and Spider, looking for lessons learned during that long day. Both of them concurred on at least one point; Lynne Black was the reason that the team came home. When the Covey riders had made recommendations, he listened. It hadn’t been easy, but he didn’t argue; he didn’t challenge. He listened. Both Spider and Watkins also agreed that without Black’s leadership and heroic effort that day, the prospects of anyone on ST Alabama surviving that hellhole had been bleak.

Lynne M. Black Jr. receiving a Silver Star from Colonel Jack Warren for his actions.

Black and the medics drank until dawn of 6 October 1968. They recounted the story to all who asked and to those who didn’t, but were within earshot. Black finally lay down on a cot in the medic’s room. A medic told him about the Jolly Green crewmember Greg Lawrence that died in the earlier rescue attempts. Black was lying on his cot.

Back in Phu Bai, Black learned that ST Idaho had been inserted into target E-4 early that morning to search for an American POW camp, which was a few klicks from ST Alabama’s target. The secret war in Laos marched on.

AFTER THE WAR

Thirty-one years later, Black cooperated with U.S. Government teams searching for the remains of SOG members and all pilots and aircrews who crashed in the Prairie Fire Area of Operation. He assisted the search team trying to pinpoint where the Special Forces sergeant’s remains were located.

A few months after the unsuccessful effort, Black received a phone call from a man who identified himself as an NVA general. He said he was the colonel who led the first 50 NVA troops into battle from the long side of the L-shaped ambush, atop the rise, which was on Black’s right side on 5 October 1968. The NVA general said he had given the order that triggered the deadly ambush.

“We had an honest discussion about that day,” said Black. “The general told me that when they heard the Kingbees come in, he assembled 50 men and set up the ambush along that trail. He asked me who the American was on the recon team who didn’t lie down on the ground during the ambush. He told me that the man standing had the radio on his back. I told him that it was me; I was the radio operator. Then he said, ‘You shot me three times that day.’”

Black explained that he remembered shooting single shots into the NVA soldiers who stood to his right, firing on ST Alabama. “When he told me that, I remembered that I had shot a few of them more than once. I remember spinning them around when I shot them. Apparently, he was one of them.

“Then he told me, ‘The worst thing about having you shoot me was the fact that I was lying there, watching you kill my men, and there was nothing I could do about it.’”

Black said he and the NVA general chatted a few more minutes about the events of that fateful day in the A Shau Valley. Black mentioned that the NVA had inflicted heavy casualties on ST Alabama, killing three team members and wounding five of the remaining six survivors. “The NVA general told me that his unit had suffered 90 percent casualties that day.”

The general explained to Black the NVA were killed or wounded either in direct combat with ST Alabama or from the numerous air strikes that Black and Covey directed around ST Alabama the entire day and after the Jolly Green Giant lifted clear of the jungle.

Black then told the general that when he observed the NVA flag flying in the middle of the knoll, he assumed that the intelligence estimates of an NVA battalion of approximately 3,000 troops was accurate. The general’s response ensured ST Alabama’s place in SOG history.

“No,” the general corrected Black, “It was a division. We had about 10,000 soldiers of the Army of North Vietnam there that day.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — John Stryker Meyer entered the Army Dec. 1, 1966. He completed basic training at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, advanced infantry training at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course in Dec. 1967.

He arrived at FOB 1 Phu Bai in May 1968, where he joined Spike Team Idaho, which transferred to Command & Control North, CCN in Da Nang, January 1969. He remained on ST Idaho to the end of his tour of duty in late April, returned to the U.S. and was assigned to E Company in the 10th Special Forces Group at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, until October 1969, when he rejoined RT Idaho at CCN. That tour of duty ended suddenly in April 1970.

He returned to the states, completed his college education at Trenton State College, where he was editor of The Signal school newspaper for two years. In 2021 Meyer and his wife of 26 years, Anna, moved to Tennessee, where he is working on his fourth book on the secret war, continuing to do SOG podcasts working with battle-hardened combat veteran Navy SEAL and master podcaster Jocko Willink.

Visit John’s excellent website sogchronicles.com. His website contains information about all of his books. You can also find all of his SOGCast podcasts and other podcast interviews. In addition, the website includes in stories of MACV-SOG Medal of Honor recipients, MIAs and a collection of videos.

I read John Stryker Meyer’s story from Across the Fence; what warrior’s we have. I’d like to know if John’s new book is out yet , and ready for sale?

John is still working on the book. Have you signed the petition to get MACV-SOG recognized by Congress with a Congressional Gold Medal? Here’s the link: https://chng.it/PMYRxm4dDP. Without question these men deserve this recognition.

My unit, the 571st Military Intelligence Detachment, often briefed and provided targets for the Green Berets in Da Nang, Vietnam in 1971-1972.

Happy to have already signed the petition!

Thank you Bob!