AN EXCERPT FROM

BEYOND THE

CALL OF DUTY

CALL OF DUTY

The Life of Colonel Robert Howard, America’s Most Decorated Green Beret

By Stephen L. Moore

Beyond the Call of Duty: The Life of Colonel Robert Howard, America’s Most Decorated Green Beret, published by Dutton Caliber, Chapter Seven, pages 60-80, used with permission.

SEVEN

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE

Bob Howard’s automatic rifle barked angrily as spent brass casings clattered onto the ground around him. With his chopper flared out over the landing zone, he carefully avoided the recon men swarming toward the extraction ship.

His shots were placed against NVA soldiers racing forward to annihilate the SOG team.

Howard helped pull both Green Berets and indigenous troopers into the slick before returning to his covering fire. Following this late-1967 mission, he would be written up for the Air Medal for heroism. Although generally issued to pilots and aircrewmen who flew on combat assault missions, the Air Medal was also awarded to SOG Green Berets for heroism in support of ground troops. In such cases, the recon man was normally praised for offering fire support with an automatic rifle, a helicopter machine gun, or a grenade launcher while helping to extract a besieged team.

Howard would eventually be pinned with four Air Medals for service in Vietnam during the period of fall 1967 through December 1968. His first was issued for a late-1967 mission for which Green Beret medic Luke Nance and First Lieutenant Gary Zukav were also issued Air Medals on the same U.S. Army general orders document. Zukav and others had been sent in to offer fire support to extract a SOG team in Laos that had declared a Prairie Fire emergency near the Ho Chi Minh Trail. (Zukav, a Hatchet Force officer who returned from Vietnam in early 1968, was best known decades later as an American spiritual teacher and inspirational author.1)

Air support was critical for recon teams, but Howard’s first love was being on the ground and across the fence in enemy territory. He had participated in only one mission as a straphanger for Joe Messer. The next man to offer Howard a chance to run recon was Sergeant First Class Robert Sprouse, a buddy of Messer’s who had joined FOB-2 at the same time as Messer. Sprouse, whose radio call sign was “Squirrel,” had started his recon work at Kontum straphanging with other teams. He was now the one-zero of ST Kentucky. Squirrel was only too happy to let Bob straphang with him, seeing the same desire in Howard’s eyes that he himself had felt months prior.

By July 1967, FOB-2 was in a state of change. Soon after Howard arrived, the first commanding officer that he had known, Major Jerry Kilburn, was transferred to Fort Bragg. Major Frank Leach took temporary acting command until July 21, when thirty-six-year-old Major Roxie Ray Hart from Georgia arrived on the scene. Hart would command FOB-2 for the next nine months. At the time of the new CO’s arrival, Kontum had a dozen permanently assigned spike teams: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming. Some teams, like ST Arizona, were just forming and had not run missions. Others had been in service since the first days of the base, and they had been commanded by multiple one-zeros during that time.

The need for straphangers like Howard was constant. Hart’s base was still building up to its full complement of sixty Green Berets, which was continually challenged due to personnel losses and injuries. During June and July, there were several casualties, some resulting from a midair collision between two heavily loaded Vietnamese CH-34 helicopters returning from a cross-border mission on the Fourth of July. Six members of ST New York, including two Green Berets, were killed in that crash. Two weeks later, on July 15, the one-zero of ST Florida was killed in an NVA ambush across the fence.2

Howard thus found teams regularly in need of a temporary replacement, a fair excuse to leave his supply room duties behind for several days each time. By late summer of 1967, he was getting into the field on a more regular basis, either with a spike team, with one of the temporary Project Omega B-50 teams, or with a Hatchet Force operation. He did not bother keeping notes on each of his missions. The exact dates of some have been lost over time since many MACV-SOG mission records were destroyed after the Vietnam War.

Howard quickly became known as a solid, dependable, and fearless straphanger for anyone in need. Although he was not a regular at the base club during his first year at FOB-2, the Green Berets sharing drinks there heard plenty about his exploits in enemy territory. His first recon mission with Joe Messer might have been void of enemy contact, but Howard found or created plenty of action on many of his subsequent trips into Laos and Cambodia.

One of the teams that Howard volunteered to join was assigned a nineteen-day mission to explore small east-west valleys near the Laos–North Vietnam border to identify potential escape routes for downed American pilots. Howard and his team located little-known mountain passes through which U.S. aviators evading capture in North Vietnam’s panhandle could escape safely into Laos. Gathering such intelligence was vital work conducted by SOG recon men, but Howard preferred to deliver devastating blows to NVA forces.3

Howard dreamed up one clever strike while working in his supply room. One of his military specialties was demolition, so he concocted a plan while waiting for his next straphanger opportunity. He took an old footlocker and spent hours painting it bright red. Howard’s biggest challenge was convincing his Kontum intelligence officers to allow him to rig it up to be a special booby trap. Inside it, he packed about eighty pounds of aging TNT that was beginning to sweat nitro. He dual-primed the deadly locker with a pair of five-minute-time-delay detonators.

As the team was airlifted into Laos the next day, Howard maintained a hand on the bright red locker to keep its contents steady. His Montagnard comrades eyed the strange box with nervous looks but said nothing. At the LZ, the first recon men swarmed out of the chopper as Howard struggled to lift the heavy box. Setting it level in the tall grass, he motioned his final Yards from the bird just before the pilot pulled away. Howard knew that NVA trackers routinely monitored the insert of Green Beret teams, and he had a special surprise in store for them.4

The team quickly raced into the jungle, giving the appearance of being in such haste that they had forgotten their supply locker. Howard’s team circled back through the foliage and took up station nearby to watch. As expected, several North Vietnamese soldiers soon swarmed the LZ and began prying open the locker, whose time-delay detonator had been set. “That bastard blew a hole in the ground,” Howard recalled. “It blew shit for a quarter of a mile. That’s how much TNT we had in it.”

Howard’s reputation grew around the base as stories came back of his exploits across the fence. Also in 1967, his team was assigned to monitor NVA truck traffic at night along Highway 110. Several nights into the assignment, the sound of a rumbling engine soon broke the silence of the dark jungle. Howard crept up alongside the road and lay in wait. As a loaded troop truck rolled past his position, he sprang into action. He ran alongside the truck, clutching a Claymore detonator in his hand. Howard tossed the mine into the truck full of startled NVA soldiers. At a full sprint, he disappeared back into the jungle as the timefused Claymore exploded seconds later, destroying the vehicle.5

Hailing from Arkansas, Staff Sergeant Larry Melton White was about the same age as Howard, and he had arrived at Kontum in early 1967. His first missions were carrying radio for one-zero Johnny Arvai’s ST Maine and on other cross-border operations with one-zero Charles Smith of Project Omega’s RT Brace. By the fall, White had assumed command of Arvai’s team. His code name was “Six Pack,” referring to his preference of running a smaller spike team with three Americans and three indigenous members. He soon befriended Bob Howard and allowed him to straphang with his spike team.

“I never saw him show any fear whatsoever,” White recalled of Howard. He had never experienced a soldier like this supply sergeant. “He would do anything you wanted him to do. You couldn’t ask for a better guy on a team.” White found Howard to be subdued in peaceful situations, not one to make a lot of idle small talk around the compound.

In late 1967, Howard accompanied White’s team on five missions. On their first, they made no contact at all. They went in as a “pilot team” assigned to flush out local Montagnards and bring some of them back to Kontum. Upon exiting their chopper, the team ran for a nearby wood line to take cover. There White and Howard discovered many eroding wooden caskets lying on top of the ground in the forest. It seemed odd, but they pushed on in search of the NVA-sympathetic Yards reported in the area. “We spent a number of days in there but never saw a living person,” White recalled. “We were going to take the entire bunch and bring them back to Kontum. We were going to deny the NVA of their use. But we guessed they had moved them out of the area.”

Soon after this luckless mission, Howard accompanied Six Pack White’s team on another trip across the fence. Along with three Yards and a junior man carrying radio, they were inserted by a Huey and accompanying gunships from Dak To into Laos. All six men on the team dressed in regular green jungle fatigues with soft boonie hats. “We added black spray paint, which made it an even better-style camouflage,” said White. Going into the combat zone as one-zero, he always carried a high-power Browning automatic pistol strapped to his waist for easy access, in the event he was forced to ditch his gear in a running firefight.

In Laos, his team moved quietly through the jungle in search of their enemy. During the day, White insisted that his men keep moving at all times. “We would move from daylight to dark,” he said. “I didn’t take breaks or sit down for lunch. That’s where most of the teams got into trouble. If we really needed a rest, we’d lean up against trees for a while.”

Howard and his fellow teammates simply munched on dried sardines and indigenous rations. These little bags of rice, dried peppers, and various proteins required a small amount of water poured in from the soldiers’ canteens. “You’d just fill it up to the line, and then you could eat your rice as you went along through the jungle,” White recalled.

Bob Howard in the field wearing tiger-stripe camouflage, talking with his one-zero Larry White. (Robert L. Howard collection, courtesy of Melissa Howard Gentsch)

“You could also make a rice ball to eat, or take bites of what we called ‘donkey-dick’ sausage.” Those who were becoming drowsy or did not wish to eat could simply pop an amphetamine tablet to keep them alert and curb their appetite.7

White and Howard kept their team moving near the Ho Chi Minh Trail the first two days. Unlike other teams, where the junior man carried the team radio, Six Pack White always insisted he would handle that duty. “The only way you’re going to get pulled out of there is if you have a radio,” he reasoned. “My other stuff was distributed amongst the team.” They moved from daylight to dark. Once sunset approached, the jungle became dark very quickly. At that point, White advanced his team near the trail they were shadowing and then employed a fishhook maneuver to double back a short distance.

Settling down near the trail, he had his team stretch out to rest for the night. “We would lay toe to toe in a circle,” White related. “We didn’t have a guard or any of that stuff. I would get me a stick, because those Montagnards had respiratory problems. They often coughed and hacked and carried on. If someone would act up during the night, I’d hit them or tap them with that stick to get them quiet.”

Shortly before daybreak, the team was on the move again. “You’d move your tail gunner back and start another day,” he said. During their movement, White and Howard became aware that trail watchers had spotted their team. From time to time, they heard signal shots in the distance as a tracker tried to rally other troops.

“When you’re being tracked, you really can’t shake them,” said White. His team simply kept tabs on where signaling sounds were coming from in order to determine which direction they should move next. “We carried silenced .22s, and sometimes we would pop a guy who was following us too close,” White added. “We surprised them instead of them surprising us. You’d just take out a few of them and keep going.”

The trackers began to move too close to their team, so White asked Howard to put out toe poppers to slow them down. Similar to hockey pucks in appearance, M-14 antipersonnel mines were one of many special toys utilized by Special Forces men to stop pursuing opponents. Composed largely of plastic, the small, thick devices required only about thirty pounds of pressure to detonate enough explosives to remove a man’s foot. As the pursuers gained on the team, Howard ripped off his shirt and tossed it across a bush after quickly planting a few toe poppers in front of it. Minutes later, he heard two explosions after his curious followers approached to examine the shirt. White’s team was thereafter free of these trackers.8

During their final day across the fence, White’s team finally made heavy contact with a large NVA force. A firefight ensued, and he called his Covey Rider for an extraction. Two Hueys moved in, each with four McGuire rigs hanging below them; the canopy was too thick to lower extraction ladders. Invented by Special Forces sergeant major Charles T. McGuire, the McGuire rig was a hundred-foot rope with a six-foot loop fitted with a padded canvas seat at the end. Each Huey could drop four weighted rigs, or “strings” in recon jargon, two to each side. As the first bird went into a hover, Howard and White had their indigenous team leader load two of his men and one American into the strings. The first Huey pulled away, leaving White, Howard, and one Yard laying down covering fire as the second bird dropped low. The three slipped into their rope seats and were soon pulled through the heavy canopy, branches slapping at their arms and faces as they were lifted clear.

Although his team had failed to grab a prisoner, as White had hoped, they had at least all been extracted without injury. He appreciated the eagerness of Bob Howard as his volunteer one-one each time they ran together. “He was the only man I’d ever seen whose pulse rate never got up,” White recalled. “He was just calm, cool, and collected.”

On their fifth mission together in Laos, Howard and White used Claymores with time-delay fuses to destroy a vital NVA fuel pipeline.

White would be transferred to another base in early 1968, but it was not the last time he would run recon with Staff Sergeant Howard.

In September 1967, Bob received a new boss in the S-4 division. Thirty-two-year-old Captain Eugene Crouch McCarley Jr., who hailed from Wilmington, North Carolina, became Kontum’s new logistics boss. Like Howard, he was tough as nails and he already had advanced Special Forces training.

Gene McCarley had completed Officer Candidate School in August 1962 at Fort Benning, Georgia. He had commanded a wide variety of SF detachments and graduated from the Army’s Special Warfare School. Despite his experience, McCarley still arrived at FOB-2 as an FNG without experience running a Prairie Fire or Daniel Boone mission. “Anybody that went to Kontum had to run one mission with a recon team,” McCarley recalled.9

Gene’s first trip across the fence was with SFC Don Steele’s ST Florida. His one-zero was wounded during that insert, and Captain McCarley was tapped to take over Florida when the team’s other Green Beret was deemed to be suffering from combat fatigue. Gene had no fear of taking on the toughest assignments. “I always ran with a small team, so it was usually just myself and one American and three or four indig,” he remembered. “I was crazy as hell.”

He found his supply sergeant to be equally bold in any situation. One day, Howard and his new captain checked out a deuce-and-a-half truck to secure supplies from nearby Kontum City. As they crossed a small stream, the makeshift bridge they were using partially collapsed, preventing them from returning. As McCarley and Howard surveyed the situation, potshots rang out from nearby.

A pair of Viet Cong soldiers had advanced and they were firing on the Green Berets with single-shot rifles. It was McCarley and Howard’s first firefight together—but it was never even a contest. Both men were expert shots and they were heavily armed. In less than a minute, they downed both opponents.10

After that moment, McCarley occasionally used Howard when he needed a straphanger for ST Florida. Neither man was wounded on their late-1967 missions, and they developed a deep trust in and friendship with each other. “Howard just loved combat,” Gene recalled. “He was tough, and he just loved to fight the enemy. He was one hell of a man.”

Captain McCarley would later, in early 1968, be assigned to take command of Company B of FOB-2’s Hatchet Force, which soon became officially known as the “Exploitation Force.” “Politicians didn’t like the word ‘Hatchet,’” McCarley remembered. “It sounded too sinister. We changed names at the FOB so many times, but the mission never changed.” During his time with the Exploitation Force, McCarley would call on Howard to join his company when he needed an extra man he could depend on. Sergeant First Class Johnnie Gilreath Jr. was another one-zero who was more than happy to let Bob Howard straphang with his team. A youthful-looking twenty-four-year-old Tennessean with dark hair and a thin mustache, Gilreath was fearless in the field. He had arrived in Kontum in April 1967 from the 10th Special Forces Group in Germany, along with Sergeant Larry David Williams. With a year of Vietnam service under his belt already, Gilreath ran a few missions with ST Colorado, one of Kontum’s original teams.

By August 1967, Johnnie had taken over Colorado after his one-zero, SFC Jerry “Pinky” Lee, received new orders. Larry Williams, whose SOG code name was “After Shave,” became Gilreath’s one-one. He carried the PRC-25 radio on at least eight missions that their team ran across the fence, and on in-country patrols. In September 1967, they pulled Bob Howard in to strap for their team for a mission into Laos, where they managed to break contact with an enemy force and be safely extracted.11

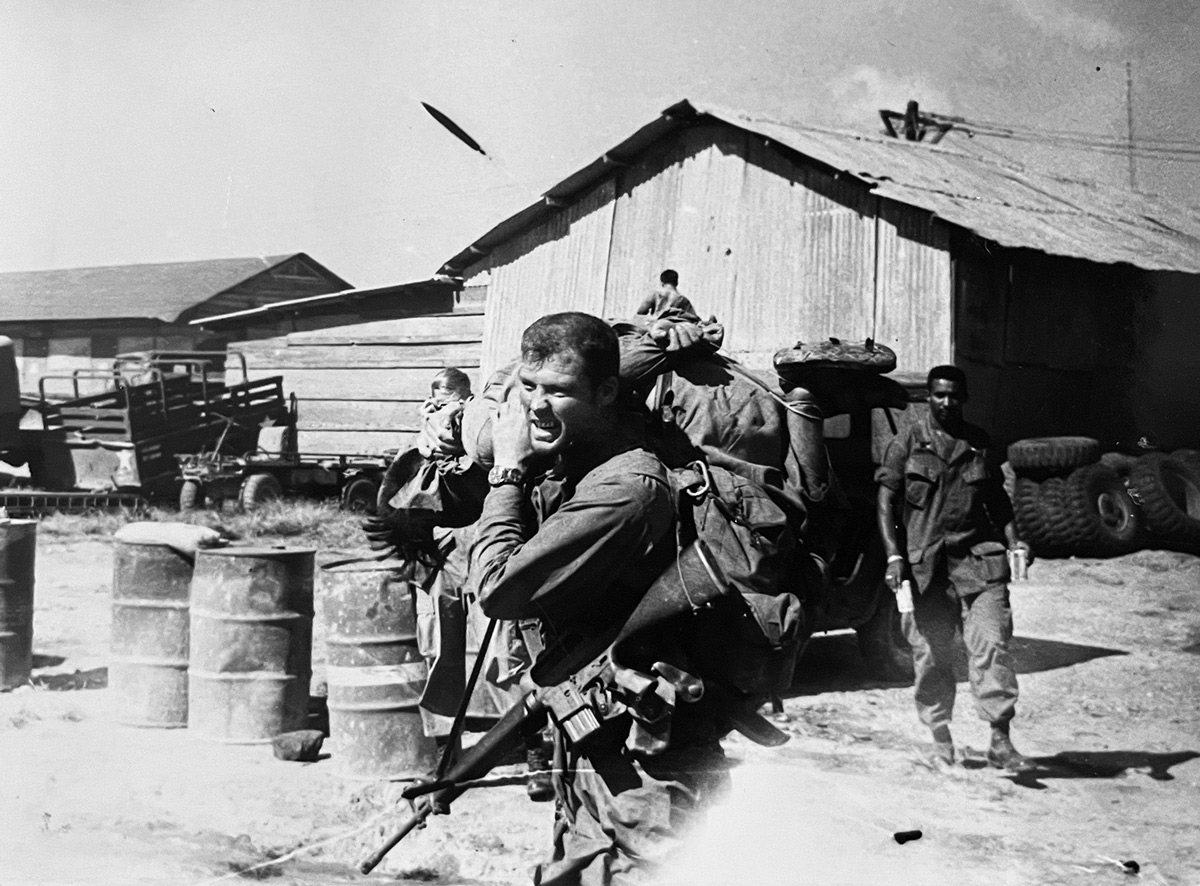

Sergeant First Class Bob Howard with Sergeant Larry Williams (right) of Spike Team Colorado. Howard accompanied Williams and ST Colorado as a straphanger on multiple missions in late 1967. (Jason Hardy)

Howard’s toughest mission with Spike Team Colorado came in November 1967. Johnnie Gilreath’s team had orders to insert into southeast Laos for a wiretap operation to gather intelligence on NVA operations. Their target area was H-9, or Hotel 9. SOG command used alphanumeric designations to divide up the maps of Laos and Cambodia into six-kilometer-by-six-kilometer target boxes. Target areas approved by both the White House and SOG headquarters in Saigon were then relayed to the forward operating base’s S-3 (operations) shop. Together with their S-2 (intelligence) officers, the S-3 team would select a team for each mission and prepare briefing materials for the chosen one-zero.12

During their early months of running recon, FOB-2 men were always flown into enemy territory in CH-34 Kingbee choppers operated by the Vietnamese Air Force’s 219th Helicopter Squadron. But as ST Colorado reviewed their mission plan on November 18, Gilreath announced that they would be inserted by American pilots this time.

In October, the 57th Assault Helicopter Company (AHC) began setting up camp near FOB-2 at the new Kontum Army Airfield. They had two platoons of UH-1H model Huey helicopters and eight UH-1C Huey gunships. The “slicks” were lightly armed, while the more heavily armed gunship division 1C choppers went by the call name “Cougars.” The 57th pilots nicknamed their slicks “Gladiators,” and used radio call signs such as “Gladiator 167.”13

On the morning of November 19, Gilreath, Williams, and their Yards were inserted into Hotel 9. Low on water after two days in denied territory, ST Colorado consulted its maps and moved toward a stream located in their area. Gilreath and his men assumed position on a hill while Williams took a Montagnard down the hill to stock up on water. While doing so, Williams noticed massive bags of rice stacked by the hundreds along with large quantities of ammunition. Upon reporting this find of NVA supplies to Gilreath, the team relayed a message back to base via their circling Covey Rider.

Major Hart ordered a Hatchet Team platoon to be flown into the area immediately to destroy the enemy supply dump. This Exploitation Force would have its hands full with the NVA goods, so Bob Howard volunteered to lead a small recon team in as well. He would guide the Hatchet men to the dump area and then scout for approaching NVA to prevent any loss of men while the supplies were destroyed.14

Howard’s recon unit and the large Hatchet Force platoon were flown in by 57th AHC slicks. On the ground, one-one Larry Williams helped prepare a large LZ by using a Claymore to blow down a tree. He then took one of his Yards down to inspect the NVA rice cache. Gilreath and the remainder of ST Colorado remained in their hillside position as the Kontum Hueys began settling down on the oversized landing zone.

His rucksack loaded with provisions and weapons, Howard was ready to leap off the chopper. Clutching his M16, he anxiously pressed his boots on the skids, watching the waving grass below as his Huey flared out. A short distance away, Williams tripped an ambush as the Hatchet Force men began pouring out of their UH-1Hs. He and his Yard ran up on an NVA soldier near the stockpile and exchanged fire with him.

The instant Williams and his Montagnard teammate commenced shooting, the calm jungle all around the LZ erupted into violent explosions of small-arms fire and machine guns. “All hell broke loose,” recalled Williams. “We had stirred up a hornet’s nest!”15

Unseen machine-gun nests unleashed volleys of bullets into the choppers. The last of the Hatchet Force men raced for nearby cover. By the time the slicks cleared the LZ, three had been badly shot up by ground fire. Howard and his men now had a hot mission—and they needed to take out enemy resistance. Howard swiftly guided the Kontum platoon around the dangerous ambush zone and made contact with one-zero Gilreath’s team. The group had gone in with a new first lieutenant as a straphanger, an officer who had hoped to earn his Combat Infantryman Badge.

Gilreath left this officer in charge of some of his Yards. He pushed forward with Williams, Howard, and the small security element that Howard had brought in. The Hatchet Force Green Berets and their Montagnards quickly set to work, slashing open the hundreds of bags of rice and salt and setting fire to the NVA goods. But this process would take some time, due to the enormous stockpile in front of them. Howard would have to keep the NVA men at bay if the mission was to succeed.

Spike Team Colorado and the Kontum Exploitation Force faced heavier enemy opposition than they had expected. The firefight Williams had triggered during the relief team’s insert soon brought plenty more action. Enemy gunners moved in close enough to man machine-gun bunkers near the bivouac area that the American recon forces were in the process of destroying. Bob Howard, leading a small group of Yards in search of the enemy gun nests, suddenly encountered four North Vietnamese soldiers charging toward him. With a single magazine, Howard gunned down all four NVA with his M16. No sooner had he eliminated this threat than his team faced an even greater challenge. A short distance away, a camouflaged machine-gun bunker roared to life. Howard, Gilreath, Williams, and others hit the deck and tried to take cover. Bullets pierced the ground all around them. Although Williams and others had their jackets ripped by slugs, none of them were directly hit.16

Howard carrying a SLAM POW. Read more about SLAM (search, locate, annihilate, monitor) operations in Chapter 10 of Beyond the Call of Duty. (Robert L. Howard collection, courtesy of Melissa Howard Gentsch)

In the meantime, the Hatchet Force men continued to destroy the NVA battalion’s food cache. During this work, they uncovered a thousand rounds of recoilless rifle ammunition and seven hundred rounds of AK-47 ammunition. The Kontum men utilized mortars to detonate all of this ammunition, but the massive volumes of explosions only further riled up the nearby NVA. Enemy soldiers raced forward to man other pill-boxes in the vicinity. Their growing volume of firepower would play hell on Howard and his comrades.

One-zero Gilreath was still learning just how brave Robert Howard was. “He ran toward the enemy at all times,” he later related. Machine-gun bullets continued to stitch the ground all about the small team of Green Berets and Montagnards. Oblivious to his own safety, Howard began crawling forward toward the machine-gun bunker. In the process, he became aware of a lone North Vietnamese soldier firing shots at him with a rifle.

Taking careful aim, Howard put a lethal round into the sniper, then resumed his crawling toward the bunker. Steeling his nerve, Bob stood and charged. Racing to point-blank range, he used his automatic weapon to mow down all the gunners within the nest. Before he could retreat, NVA manning another nest nearby opened fire on him.

Howard hit the jungle floor and crawled quickly for cover. Sergeant Williams stood and opened fire on the second pillbox, providing cover for Howard’s retreat. His barrage suppressed fire from the nest long enough for Howard to reach safety and pull his men to a covered position. Bob then opened up on the radio, calling to the Covey Rider circling above the action. Air strikes were called in to destroy this bunker.

The NVA machine-gun nest fell silent as the aircraft pulled clear of the area. Howard inched forward to assess the bomb damage. Some of the NVA had either survived or had been quickly replaced by other soldiers. The machine gun came to life again, firing bursts of bullets at Howard. Bullets and frags from explosions began to take a toll on Howard’s body. His right clavicle was fractured by shrapnel, and minutes later another fragment or bullet ripped through his right cheek.17

Howard cheated death once again when he was hit in the face by a bullet for the second time in three years. Like his 1965 facial wound, this bullet was another ricochet that struck him in the head above his left eye. The bullet failed to penetrate his skull, but the concussion knocked him to the ground, rendering him briefly unconscious.18

Howard was in an unenviable position as he regained his senses. He was pinned to the ground as bullets sprayed out just six inches above his head. His shoulder was separated, and blood gushed from his face. But he was far from giving up. He knew his life and those of others nearby were on the line if the enemy bunker could not be knocked out. Howard removed a fragmentation grenade from his gear, pulled the pin, and tossed the grenade into the aperture of the emplacement.

A brilliant orange burst of flame erupted in the pillbox, and the explosion killed the remaining enemy gunners. With the bunker silenced once more, Howard dashed across the clearing to where his comrades were taking cover. Within minutes, fresh NVA troops manned the machine-gun nest and pinned down the SOG men.

This time Howard grabbed an anti-tank rocket launcher from one of the Yard grenadiers. A withering hail of bullets poured from the nest.

“Cover me!” Howard shouted.

Larry Williams opened fire with his automatic weapon as Howard rose to his feet and moved forward. Machine-gun bullets swept the area, but the NVA gunners were obviously frightened. Their aim was off. Howard carefully put the launcher against his left shoulder and took aim. He fired from close range and winced as the recoil jarred his broken clavicle. The rocket screamed into the bunker and exploded, tossing shrapnel, jungle foliage, and body parts in all directions. Howard’s one-man assaults, covered well by Williams and others, had eliminated two machine-gun teams in a matter of minutes.

The SOG force was now able to ease back in. As they moved up a road toward the NVA cache area, more machine-gun nests opened fire on them. Williams fired grenades at the enemy bunker, then stood to charge. He fired his M16 as he ran, wiping out the entire gun crew on his own.

Along with Howard and Gilreath, Williams continued to assault any NVA that threatened their movements. Gilreath soon deemed the area too hot to handle. Ample numbers of North Vietnamese from the battalion remained, and their return fire increased. By this point, the Hatchet Force had succeeded in destroying all of the enemy’s ammo pile and a good portion of the food cache.

Gilreath radioed in extraction choppers and began moving the large force back through the jungle hundreds of yards toward their original LZ. One by one, Huey slicks dropped in to begin pulling out the dozens of Montagnards and Americans.

By the time the last chopper lifted free, the entire Kontum force was safely extracted, with only Staff Sergeant Howard wounded. Heavy air strikes were called in to plaster the NVA platoon and any surviving supplies.

Howard’s wounds were not life-threatening, and he was quickly patched up by Army medics. Although it was the second time he had been wounded in the Vietnam War, November 21, 1967, would mark the first date on which he was officially written up for a Purple Heart for his injuries. For his heroism in the assault on the NVA platoon, Larry Williams would later be pinned with a Silver Star.

Soon after the FOB-2 men were returned to their base, one-zero Johnnie Gilreath and Howard received a summons. Chief SOG Jack Singlaub had them flown to Saigon on a C-130 Blackbird to brief his boss, General William Westmoreland, who was clearly impressed with the SOG mission. Gilreath and Howard detailed their individual actions and those of their accompanying Hatchet Force. The four-star general paused, then asked if there was anything he could do for them.

“Sir, I’d like to go to flight school and become an aviator,” said Gilreath.19

Westmoreland promised the ST Colorado team leader a commission and the chance to enter flight training. Gilreath was the second one-zero from FOB-2 to receive a battlefield commission to become an officer. The first had been Dick Meadows, whose recon team had captured a number of enemy prisoners during the early months of Kontum’s history. Weeks after the meeting with Westmoreland, Gilreath was sent to Command and Control North (CCN) in Da Nang for a special mission on December 10. Operating with the 1st Cavalry Division in A Shau Valley, Second Lieutenant Gilreath earned a Bronze Star for this mission before returning to FOB-2 to command a Hatchet Force platoon. He would eventually retire as a lieutenant colonel after nearly twenty-eight years of military service.20

As for himself, Bob Howard merely asked that he be allowed to continue active combat duty from Kontum. Westmoreland and Singlaub were only too happy to oblige their eager Green Beret. His base commander, Major Hart, had Howard written up for the Medal of Honor for his selfless assaults against the NVA machine-gun nests on November 21. In the end, the paperwork stalled out, and the FOB-2 supply sergeant was instead issued the nation’s second-highest award for valor, the Distinguished Service Cross.

Howard receiving his Medal of Honor in 1971 from President Richard Nixon. (Robert L. Howard collection, courtesy of Melissa Howard Gentsch)

Such awards were generally not swift in being processed. In Howard’s case, his DSC was not formalized until May 2, 1968, nearly six months after the action. It cited his “extraordinary heroism” while being subjected to “a withering hail of bullets.” It further praised his “fearless and determined action in close combat” while allowing his patrol to destroy the enemy cache.21 Staff Sergeant Howard was little concerned with what medal was eventually pinned to his chest. His tour of duty in Vietnam was far from over, and it would not be the last time his superiors considered him worthy enough to be written up for the Medal of Honor.

Endnotes

1. “5th Special Forces Group Decorations”; “Gary Zukav with Fellow Veterans (Part I),” video. click to return

2. Moore, Uncommon Valor, 91– 94. click to return

3. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 70. click to return

4. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 129. click to return

5. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 204. click to return

6. White, telephone interviews. click to return

7. White, telephone interviews. click to return

8. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 150. click to return

9. McCarley, telephone interview. click to return

10. McCarley, telephone interview. click to return

11. Williams, telephone interview; Gilreath, telephone interviews. click to return

12. Greco, Running Recon, 54. click to return

13. “1967 Gladiators– Cougars.” click to return

14. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 204. click to return

15. Williams, telephone interview. click to return

16. Williams, telephone interview. click to return

17. Robert L. Howard Collection, Purple Heart citations. click to return

18. Robert L. Howard Collection, medical and military records; “Recon Courage Under Fire.” click to return

19. Plaster, SOG: The Secret Wars, 205. click to return

20. Gilreath, telephone interviews. click to return

21. Robert L. Howard Collection, Distinguished Service Cross citation. click to return

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Stephen L. Moore is a sixth generation Texan who graduated from Stephen F. Austin State University, where he studied advertising, marketing, and journalism. He is the author of two dozen books that primarily cover military non-fiction and Texas history. He and his wife Cindy live in North Texas, where Steve works as the marketing director for a Dallas-area electronics manufacturer. Learn more at stephenlmoore.com.

Leave A Comment