BEIRUT,

Lebanon

(1983)

By Jim Wiehe

CW3 (Ret)

ODA 231 / 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne)

Originally published in the July 2021 Sentinel

In the summer of 1983, a mini-war — a sideshow to the larger chaos inside of Lebanon erupted in the Chouf Mountains. The Syrians refused to remove their 30,000 troops stationed inside Lebanon; Israeli deployments depended on the Syrians, the fighting in the Chouf Mountains spilled over onto the streets of the Lebanese capital. The Militias owned street corners, neighborhoods, and competing criminal enterprises that dabbled in everything from smuggled goods to heroin and arms. Ownership of the street corner could change in the muzzle-flash of a close-quarter killing. A checkpoint belonging to a Sunni militia in the morning could have a photo of the Ayatollah in front of the sandbags by evening. A militia that was anti-American one day could change its loyalties and suddenly change. A Druze militia, loyal to Progressive Socialist Party leader Walid Jumblatt, augmented security around the British Embassy and provided an invaluable and reliable ring of security surrounding the chancery where the British and American diplomats worked.1

Checkpoints in Beirut were manned by pill poppers, hashish smokers, and psychopaths. A motorist who answered a question incorrectly, or who belonged to the wrong religion or militia, could be dragged out of his car, and shot point-blank in the head.2

In 1982, the United States proposed a Lebanese Army Modernization Program to be implemented in four phases. The first three phases entailed the organization of seven full-strength, multi-confessional army brigades, created from existing battalions. It was during these early three phases that MTT’s from the 10th Special Forces Group (A) were sent to Beirut to perform a Foreign Internal Defense (FID) mission.

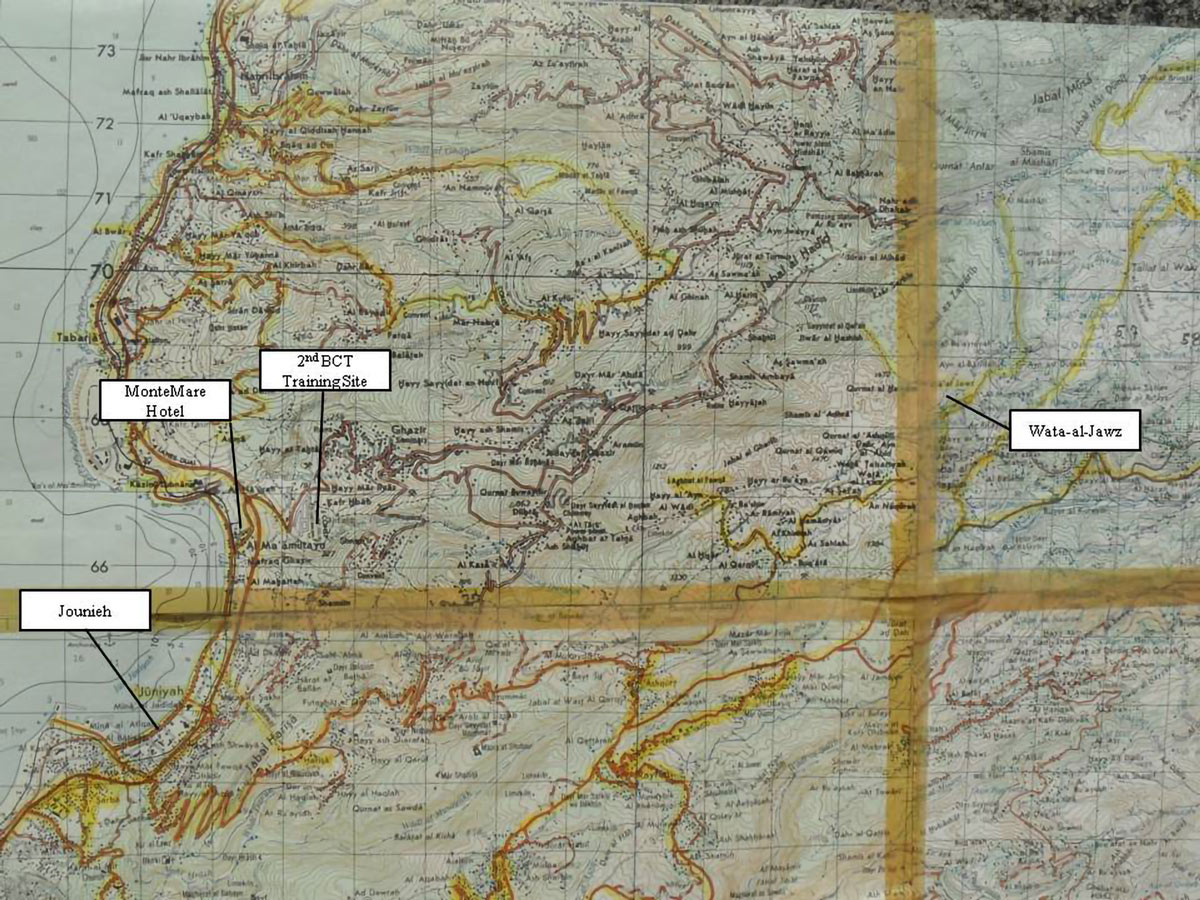

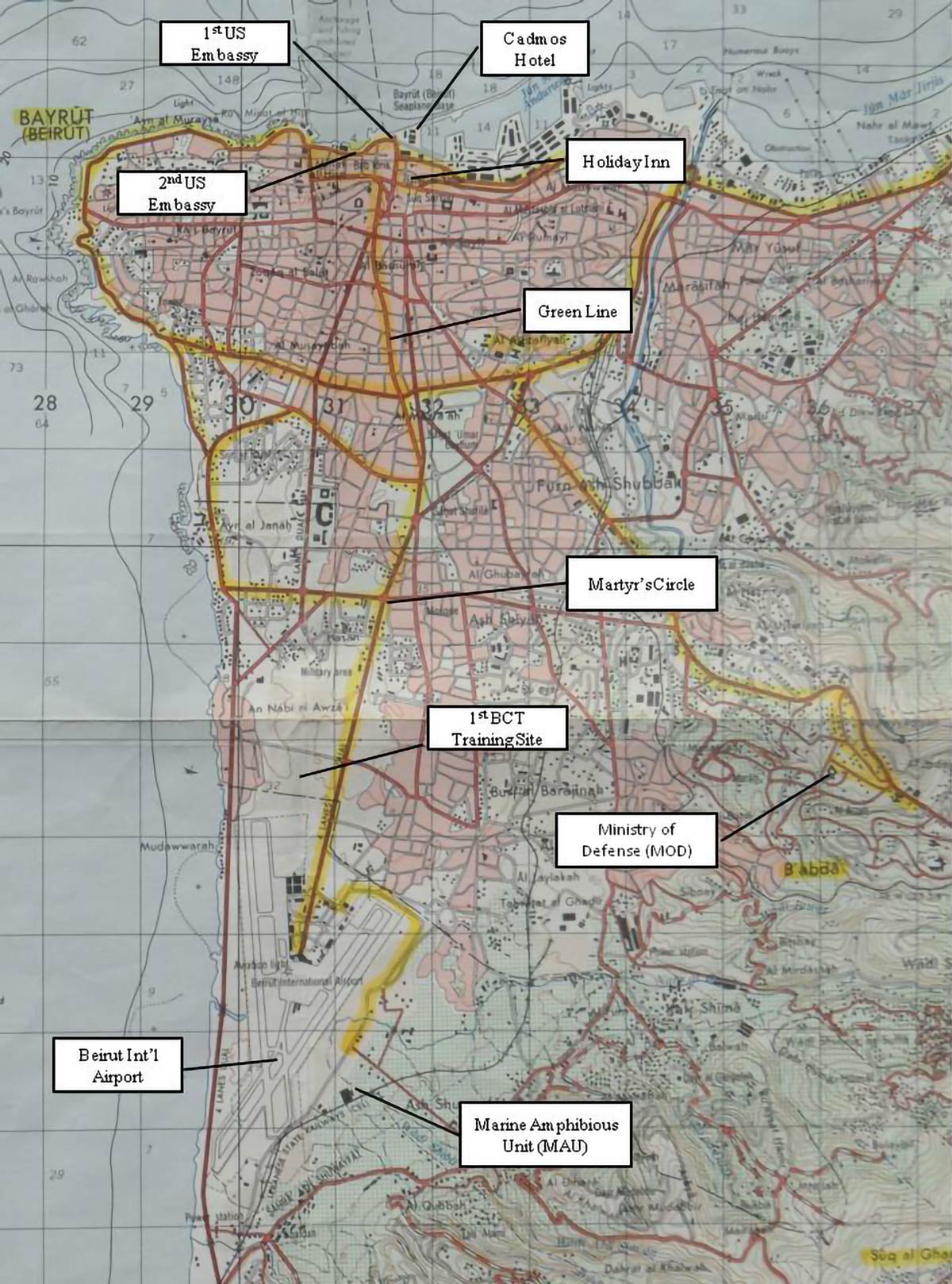

Beirut City Maps depicting training area locations. (Courtesy James Wiehe)

10th Special Forces Group (A) in Beirut, Lebanon (1983)

From 11 March 1983 to 25 October 1985, the 10th Special Forces Group deployed seventeen separate Mobile Training Teams (MTT) into Lebanon.3 These teams performed a Foreign Internal Defense mission to advise and assist the Lebanese Army Training Centers. The MTT’s and the Lebanese Army developed a training program for over 5,000 officers, NCOs, and Soldiers. The newly trained Officers and NCO’s became the nucleus for follow-on MTTs and acted as interpreters and trainers. Training sites at Beirut and Adma provided basic training; Safra was used for unit training; Wata Al Jawz was used for unit combined arms live-fire, and Haef Jumayyid was used for urban live-fire training. Training programs for NCO combat leaders, basic training for over 900 LAF conscripts, long-range reconnaissance training for the Lebanese Rangers and advance unit training and maintenance for Mechanized Units were also conducted.

These teams performed a Foreign Internal Defense mission to advise and assist the Lebanese Army Training Centers. The MTT’s and the Lebanese Army developed a training program for over 5,000 officers, NCOs, and Soldiers. The newly trained Officers and NCO’s became the nucleus for follow-on MTTs and acted as interpreters and trainers. Training sites at Beirut and Adma provided basic training; Safra was used for unit training; Wata Al Jawz was used for unit combined arms live-fire, and Haef Jumayyid was used for urban live-fire training. Training programs for NCO combat leaders, basic training for over 900 LAF conscripts, long-range reconnaissance training for the Lebanese Rangers and advance unit training and maintenance for Mechanized Units were also conducted.4

10th Special Forces Group Deploys MTT’s

Over the course of the years, there has been much speculation as to how the 10th Special Forces Group received the Lebanon missions and not the 5th Special Forces Group? As per my conversation with BG Potter, he stated that:

“1/10th Gp and Det A were resident EUCOM assets and their capabilities known by the EUCOM staff and that the Mediterranean to include Lebanon was within the EUCOM area of responsibility.5

On March 20, 1983, thus began the 10th Special Forces Group involvement with rebuilding and training the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF). CW2 (Ret) Lou Pacelli, one of the original members of MTT #1, explained that:

“Instead of deploying as a Detachment, we were chosen as individuals to be put together as a composite team. We were ordered to report to the Commander’s office and asked to volunteer for a classified assignment. We received a warning order to prepare for a mission to the Republic of Lebanon to train and assist them in small unit tactics. I immediately volunteered and was put into isolation at the 10th Group isolation area. The majority of the team was assigned to teach basic infantry tactics, both mounted and dismounted. I was placed in the Basic Training Committee. The Committee consisted of five members. The team was composed of personnel from all three companies in the battalion. Our team consisted of; the Team Sergeant, Master Sergeant Michael “Mick” Roberts and Sergeant Tom Greco from Charlie Company, Sergeant First Class Wayne John, Staff Sergeant Sam Joseph and myself from A Company. We were later joined in country by Staff Sergeant Larry Hoff.”6

MTT #1: (L-R) sitting: SGT Ryan, SSG Mc Daniel, SSG Hobbs, SFC Ellisen, SSG Mc Kenzie. Standing: 1Lt Jesmer, SSG Hicks, SSG Hurley, and SSG Davis. (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

Isolation and mission prep was particularly challenging for all MTT’s leaving Ft. Devens; lack of intel, no language training, and the promise of needed supplies on the training end. As was the case with all MTT’s, members were chosen at higher, subject matter was assigned and rehearsed and normal POR activities, pre-mission medicals, and shots were updated along with new identification cards for junior enlisted personnel. All personnel in the grades E4/E5 were given the brevet rank of E-6, to include ID cards. Financial support was coordinated between SATMO and the 10th Gp Comptroller for individual payment and disbursement of advances. A request for 80% of the 179 days was requested, but only 55% was granted. Subsequent payments would be made after completion of travel vouchers while in country and mailed back to Ft. Devens, MA.

The Course of Instruction implemented by the Cadre Training MTT consisted of twenty-eight days. Actual training days of this block was limited to twenty-three days due to the Lebanese Army desire for a two-day break approximately half-way through the course and the required movement days to move the battalions from the bivouac site near the airport to the mountain training locations (Roumieh and Wata al Jawz) and back to the original bivouac sites. Additionally, the twenty-eighth day of the cycle was used for the final Inspection/Graduation Ceremony activities.

The first nine days of training were delegated to Individual Combat skills: bayonet fighting techniques, basic rifle marksmanship training, individual movement techniques, basic map reading, operation of the AN/PRC-77 and AN/VRC-46 radios and basic communications procedures, basic first aid, conditioning drills (physical training), individual combatives, land mines and basic demolitions. Additional instruction included: camouflage techniques, prisoner of war handling procedures, and throwing hand grenades. Subject areas were divided into three-day blocks. The three-line companies of each battalion were rotated through the three-day blocks in a round-robin manner. Thus, on any given day, there were actually three different days of training until all companies were rotated through the entire nine days.

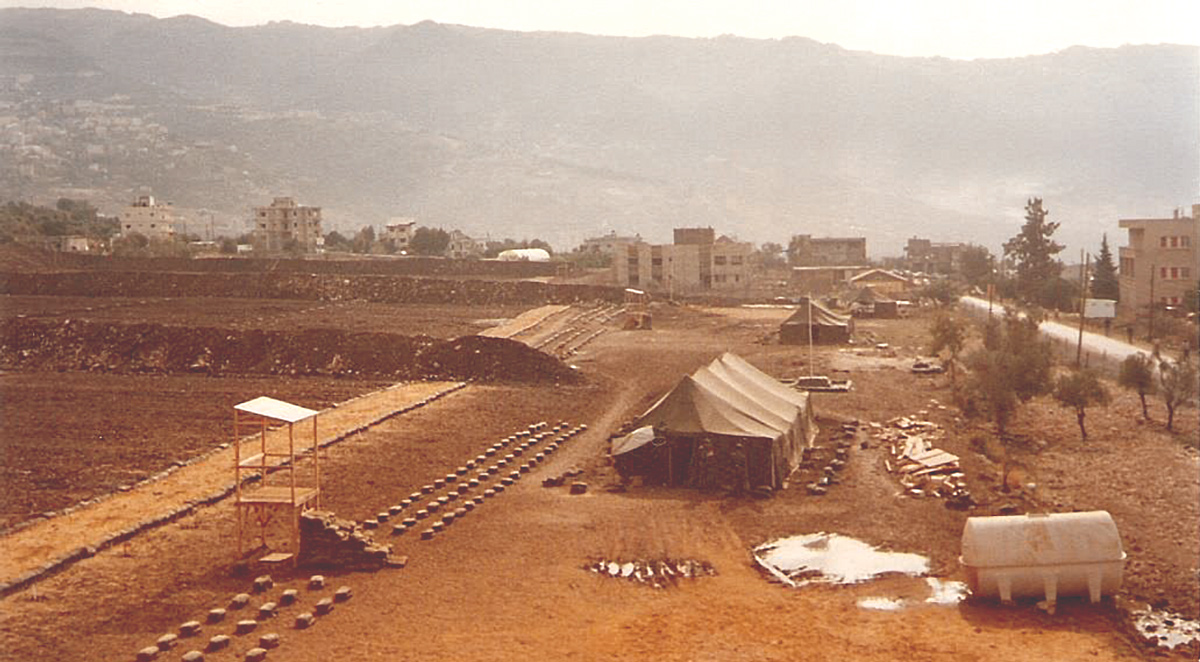

BRM Rifle ranges in Jounieh (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

The next three days were devoted to squad level training and consisted of one day of squad organization and movement, squad offensive operations (movement to contact, hasty attack, fire, and movement), squad defensive operations (hasty and deliberate defense, withdrawals). Once the squad training was moved to the Wata al Jawz training area, a fourth day of training was added; a squad live-fire exercise for the squad leader to control. One of the break days was deleted to allow for the extra day of squad training.

A typical day began at 0500 hours followed by breakfast at 0530. Breakfast meals were made available at the hotel each day before departure. Departure time was 0600 to the various training sites. By 0630 training began and lasted until 1430 hours, with only minor breaks allotted. At this time, the Lebanese Forces being trained finished for the day and had their lunch. After lunch, the leadership of the battalion being trained would receive their overhead training (a reference to training to be conducted the next day). This activity ran from approximately 1530-1630 hours each day.

The seven days of advance training in the mountain training areas (Roumieh and Wata al Jawz) consisted of five days of platoon-level training and two days of company-level training. On Day #1 of the advance training, the platoons received instruction on platoon movement techniques (traveling, traveling over-watch, and bounding over-watch). Platoon defensive techniques were taught on the second day and included the same defensive operations that the squads had received earlier. The next two days were dedicated to patrolling operations and a night practical exercise. The last two days consisted of company-level offensive movement techniques and included a mechanized movement- to-contact operation for the mechanized battalions. The mounted movement was added only after this training had been moved to Wata al Jawz as there was no location to maneuver armored personnel carriers in the Roumieh training area. The last day was dedicated to the company-level live-fire exercise where all the weapons systems organic to the company were employed. Additionally, the 81mm mortar crews and the 106mm Recoilless Rifle crews were given six days of instruction prior to the live fire exercise. The weapons employed in the live-fire exercise consisted of mortars, recoilless rifles, .50cal heavy machine guns mounted on APCs, Mag 58 machine gun, M-60 machine guns, RPGs, and the individual rifle, either M-16 or G-3.

SFC Scotty Deraps conducting BRM training. (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

The last four days of the training were given to Urban Operations training. The soldiers were trained on individual skills during the first day of this training; rappelling, entering a building, stairwell, room clearing techniques, and booby traps. On Day #2, the squads and platoons were put through practical exercises in clearing entire buildings. On the third day, each company executed an attack and a defensive operation in a built-up area. Each company executed the attack portion twice and the defensive once. Again, the companies were rotated in a round-robin manner. On the final day of Urban Operations Training, the Lebanese soldiers received instruction on security activities in an urban area. This training focused on practical exercises in patrolling in an urban environment and check-point operations.

MTT Security

MTT#1 had developed and employed a security plan and an evacuation plan in and around the Cadmos Hotel grounds when they arrived. The plan included static positions established in individual rooms that overlooked the street side of the hotel and the area side facing the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, there was an inter-roving patrol that included all the hotel floors, the lobby, and an especially worrisome one, the basement. Contained within the hotel basement was a disco bar and parking area. The parking entrance was blocked by a dirt berm and concertina wire. The bar itself, was set in complete darkness and once you left the elevator or staircase, you were in virtual darkness.

Security of personnel while in-country was a constant and daily issue. Because of the various political factions and militias, it was extremely difficult, if not totally impossible, to identify anyone organization as making threats upon MTT personnel. Therefore, it was standard procedure to treat every area as a hostile environment. The only exception to this was the area in the vicinity of Wata al Jawz.

Personal security measures were stressed on a daily basis. Upon arrival in-country, a request was immediately forwarded to OMC for weapons and was repeated almost on a weekly basis. Finally, the MTI’s received six M-16 rifles for use in vehicles and security at the hotel. Later, 9mm Browning Hi-power pistols were issued to each member of the MTT along with “Second Chance” body armor vests. Transportation to and from training sites was judged to be the most vulnerable aspect to the cadre and to overcome that issue routes, times, vehicles, and personnel were varied in order to break up any sort of pattern that might otherwise have been exhibited. Also, except for several select instances, MTT personnel were required to travel everywhere using the buddy-system. The Lebanese G-2 also employed plainclothes personnel in and around the hotel on a continuous basis. The number of LAF guards and G-2 personnel was increased based on the threat situation and/or request of the MTT Team Chief.

Providing security at the U.S. Embassy at the request of the Ambassador were: SSG McAvoy, SFC Cooper, SFC Wiehe (seated), SSG Freidman, SFC Tabor, SFC Stockert, and SSG Shaw (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

In a phone conversation between myself and BG Dick Potter7, the then 10th SF Group Commander, he explained that “…. there were several contentious issues that arose for 10th SFG(A) during their participation of providing MTT’s to the Lebanese government…”. BG Potter’s main concern was lodging. An officer from the U.S. Army’s Office of Military Cooperation (OMC) wanted the troops housed and billeted with the U.S. Marines at the Beirut Airport. COL Potter disagreed and refused the arrangement citing his authority as a Title 10 Commander who was responsible for the care, welfare, and well-being of the soldiers under his command. COL Potter met with General Lutz (SOCOM Cdr) in Beirut, Lebanon and he was apprised of the situation and why his refusal was in the best interest of his soldiers performing the mission. Each unit deployed had established and inner and outer ring of security as they were in multiple locations conducting the training. NOTE: COL Potter’s logic, foresight, and resolve for the welfare of the soldiers who were deployed while he was 10th Group Commander proved to be the right decision. Had the MTT’s been housed in the Marine Corps Barracks at the Beirut Airport as insisted upon arrival, the possibility of those team members being seriously injured or killed on October 23 would have been inevitable.

Lessons Learned

Problems arose and lessons were re-learned with each MTT iteration. Some of the most prevalent “lessons learned” that would plague each MTT were recurring and somehow could not be solved:

- Transportation. This was a problem that never seemed to go away. The drivers (who had little to no training driving) who were assigned to drive and transport us to our training sites were constantly late or were “no-shows”. Drivers were with us for a few days and then were reassigned elsewhere and a new driver would show up. Vehicle maintenance was almost non-existent, and vehicles were constantly breaking down.

- French training. Up until our arrival, the Lebanese Officers & NCO’s were being trained by the French. There was a clear lack of participation by the Lebanese Officers and NCO’s. It was recommended that the LAF’s leadership style be patterned after the U.S. Army. A constant challenge and problem were the “aloof” manner of leadership practiced by the officers. The officers as a group did not like to set the example or get deeply involved in training to the degree practiced in the U.S. Army. They were conscientious of the position and stature, which required the careful application of criticism and instruction. Blunt and frank appraisals were rarely well-received. Officers, if required to perform the tasks with their soldiers, frequently became detractors from training and sometimes discipline problems.

- Language training. No language training was received by any MTT entering the country. Although there were up to 22 Lebanese officers and NCOs assigned as interpreters, communication problems still arose. All MTT members had to learn on the job (OJT) by doing their own research on the language or memorizing how and what was being translated. After a while, words, phrases, and commands, like those on my rifle ranges, were being picked up and rehearsed by us. There were several reasons for this: time before deployment and, as usual, lack of funds.

- In-country training support. The training support received by the MTT was less than adequate. This included support in the construction of the ranges and the ability to provide the materials necessary for the construction of the training facilities. There were no training aides or training areas identified. This lack of understanding was prevalent in the LAF G-3 and G4 until a LAF COL was placed in charge of the AUT program for the Lebanese, the problem would not get resolved.

SFC Dick Cooper with his counterpart.(Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

- Passport processing. The passport processing for MTT #2 was not as nearly the administrative problem that it was for MTT #1. The Bn S-1 was aware of all the requirements and processed the forms promptly. However, the problems arose where individuals were unable to promptly acquire a birth certificate with a raised seal from their home state. By the 3rd MTT iteration, this problem did not exist.

- S-2 support. Upon arrival in-country, there was insufficient intelligence being disseminated to the MTT’s. Additionally, this intel was also not available during isolation and team train-up. After lengthy discussions with the OMC (Office of Military Co-operation) and specifically, the April American Embassy bombing, two security personnel were brought in from EUCOM. At this point, the MTT’s began to receive daily updates through the OMB Security Officer.

- Effects of weather on training. The heat during July – August made training for the ITT personnel very difficult, but not impossible. Extra effort was made to quickly identify and treat any heat-related injuries. The heat also made it next to impossible to train in the ITT airport areas all afternoon. You were exposed to the sun all day with no shade available. Training normally stopped at 14 hours due to the extreme heat. Conversely, the heat had little to effect on the ATT personnel training in the mountains. And the snow in the mountains in March – April made it impossible to recon many potential maneuver areas. The cool, rainy winters did not stop training, but it made a mess in the lowland areas.

- During training. When the M113s arrived in-country, the transmissions were filled with shipping fluid and not the correct transmission fluid required. The shipping fluid needed to be drained and new transmission fluid added IAW the TM-10. The Lebanese did not know this and consequently burned out many transmissions.

Siege of the Cadmos Hotel

On August 29, 1983, all training of the Lebanese Armed Forces had ceased. Personnel who were transported to the training site near the airport were greeted by our interpreter, Mohammad Chukeir who quickly explained to us that the Mechanized Infantry Battalion in training had departed during the night after a message over a loudspeaker. The message told to the commander was “to defect with all men and equipment or your wives and children would be killed.” It was immediately after this conversation that it began to rain down 155mm howitzer shells from the Chouf Mountains above us. The Druze militia and the Syrian gun positions had a” direct-lay” upon us. We took several rounds and made our way back to our vehicle and departed the training site. This would be the beginning of a 30-day siege for us at the Cadmos Hotel. We assumed a “static” role and training ceased.

There is very little written of this event and only “references” by the Pacific Stars and Stripes on September 1st and September 2nd.8 Even the Marine account of what happened in Eric Hammel’s, The Root, notes that the U.S. Marines were called to evacuate us from the hotel due to safety concerns expressed by the attacking Druze militiamen. Robert Pugh, the U.S. Embassy Charge d’Affaires was summoned to the guard post at the embassy when a Druze Officer arrived (who was pro-American) and stated that “he was on an errand of mercy and had been ordered to attack the LAF unit bivouacked near the Cadmos Hotel that housed 70 U.S. Army Special Forces trainers and saw no reason to involve the American Marines, as he called the Green Berets and asked that they be removed.”9 Pugh notes on page 141-142 that: “Though there had been sufficient room, barely, for all the Special Forces trainers, the first contingent had opted to carry out its gear, and, to the amazement and ire of the Marines, their personal effects and souvenirs — including a man-sized teddy bear that took up one whole vehicle seat.”10 I have it on good authority that one of us “did indeed” take his teddy bear, but it was strapped on top of his rucksack and most likely mistaken for a full-sized rucksack.

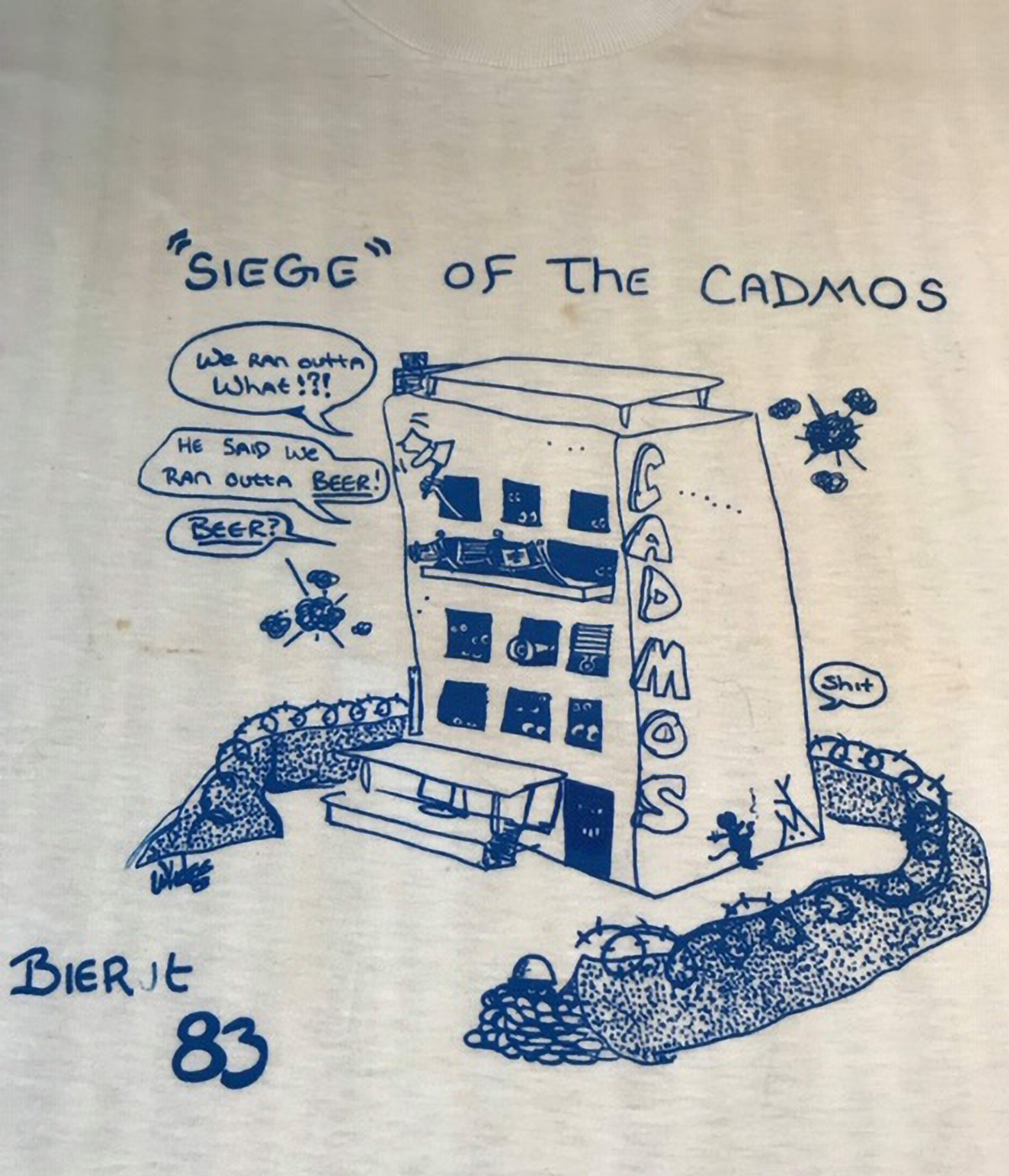

T-shirt designed by SSG Doug Wheless upon our return home. (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

On August 30th violence once again broke out in the city, this time along the Corniche and down from the newly relocated American Embassy. A Druze militia, loyal to the Progressive Socialist Party leader Walid Jumblatt, augmented security around the British Embassy. The militiamen, recognizable in their red berets and camouflage fatigues, provided an invaluable and reliable ring of deterrence surrounding the chancery where the British and American diplomats went to work each morning.11

Ten thousand Lebanese soldiers, using tanks and helicopters, launched a three-pronged attack in West Beirut to try and flush out rebellious Druze and Shiite Moslem militiamen. Both the Moslem western sector of Beirut and the eastern Christian sector came under heavy-weapons bombardment. During the day, hundreds of Lebanese Army Forces were locked in fierce combat with the Druze militiamen who were entrenched in the 25-story Holiday Inn just blocks away from us.

The hotel was prepared for combat having an eight-foot berm surrounding and topped with concertina wire and a 106mm recoilless rifle aimed out the main entryway. More importantly, the hotel had a fully stocked restaurant and bar; that is until the siege. As part of our “ring of security” while in-country, initially, there was a squad of Lebanese Army Forces situated in and around the base of our hotel. As the situation outside of the hotel and the surrounding area became more volatile, our security force was increased to a reinforced platoon size element with an accompanying M1A1 jeep with a 106 recoilless rifle. With nothing more than the underground entrance being filled with dirt and an outside dirt berm with concertina wire on top, the hotel became our Alamo. Also, on every floor of the hotel, and in strategic locations with vantage points, there were guard posts. These guard posts were manned with 2-hour shifts whenever we were in the hotel. (Note: After the ‘siege” we were issued FN FAL 7.62 rifles along with our sidearms.) The street side of the hotel was our most vulnerable side. It was just yards away from the civilians living across the street and well within shooting distance from snipers and rocket fire. Sniper fire from across the street of the hotel and an occasional RPG burst was the norm for the duration of the 30 days we were in the hotel.

SSG's Henterly (with M16 and Emerling (pistol) reacting to sniper fire. (Photo courtesy James Wiehe)

What happened next was an air-assault by a LAF rifle squad on the street directly in front of the bombed-out embassy who returned fire into the embassy with rifles and machine guns and made their way towards the Cadmos Hotel. Sometime near dusk, a vehicle convoy arrived to take all of us to the American Embassy. At the time, we were told that the ambassador (Bartholomew) had requested additional support for his Marine guards, not the other way around. There were not nearly enough vehicles to take all 70 of us, so a handful was selected to go and to take their individual kit and rucksacks along.

As we loaded up and began our departure, artillery air burst rounds exploded between us and the embassy down the street. As we headed towards the embassy, the air bursts continued to plague our movement. Simultaneously, as we maneuvered around the barriers in the street, we were suddenly dodging RPGs that were being fired from behind us. Luckily, the RPGs struck street barriers or fizzled and sparked down the Cornish like a roman candle being hand-held.

When we arrived at the embassy, we were issued 12-gauge shotguns and given a sector of responsibility as the Druze militia were now working their way through the city and being chased by the LAF. For the next two days, we continued to provide security until we were told that the Druze militiamen who were firing upon us were now seeking sanctuary in the embassy from the pursuing LAF. One can only shake his head.

When the shooting stopped, we were loaded back up and taken back to the hotel. On a side note, our team medic (SSG Doug Wheless) who was an amateurish artist created a t-shirt when we got back depicting the hotel siege.

After things quieted down a bit, we were moved to a quieter place along the Mediterranean coast further west to the coastal town of Jounieh. We had to start from scratch to establish a training area.

Footnotes:

1. Fred Burton and Samuel M. Katz. Beirut Rules, The Murder of a CIA Station Chief and Hezbollah’s War Against America, Penquin Random House, page. 91-92. 2018.?

2. Ibid. Page 92.?

3. https://www.soc.mil/USASFC/Groups/10th/history.html (Note: Original AAR from MTT #1 reflects dates as 3/20/83 – 9/9/83 in their After Action Review. These dates are again reflected in the After Action Review from MTT #2.)?

4. Ibid?

5. Ibid?

6. CW2 (Ret) Lou Pacelli notes provided, August 2020.?

7. 8/5/2019: Phone conversation with BG Dick Potter and Jim Wiehe, RE#: 10th Special Forces Group (A) 1983 MTT’s into Beirut, Lebanon. BG Potter served as Commander of 10th SFG(A) from Dec 1981 – July 1984.?

8. Pacific Stars and Stripes, Sept 1, 1983, No. 243. “Fierce battling engulfs Beirut and Sept 2, No. 244, 10,000 troops vs. Beirut militias.”?

9. Eric Hammel, The Root, The Marines in Beirut August 1982 – February 1984. Pg 138 – 142. Zenith Press. 1984.?

10. Ibid, page 141–142.?

11. Fred Burton and Samuel M. Katz. The Murder of a CIA Station Chief and Hezbollah’s War Against America, Penquin Random House, 2018.?

I got to FT Huachuca 1983 with Northern Arizona ROTC for training and saw my old teammate LeeRoy Green. He told me he had to change his last name to Harper for this operation. I asked him where they were going? He said Lebanon. I asked him what were they gonna do? He said kill a bunch a motherfuckers

Jim,

Greetings from Camp Humphreys, Korea. Thanks again for documenting our efforts there in ’83.

David,

CDR, ODA 235/MTT #2