Book Review

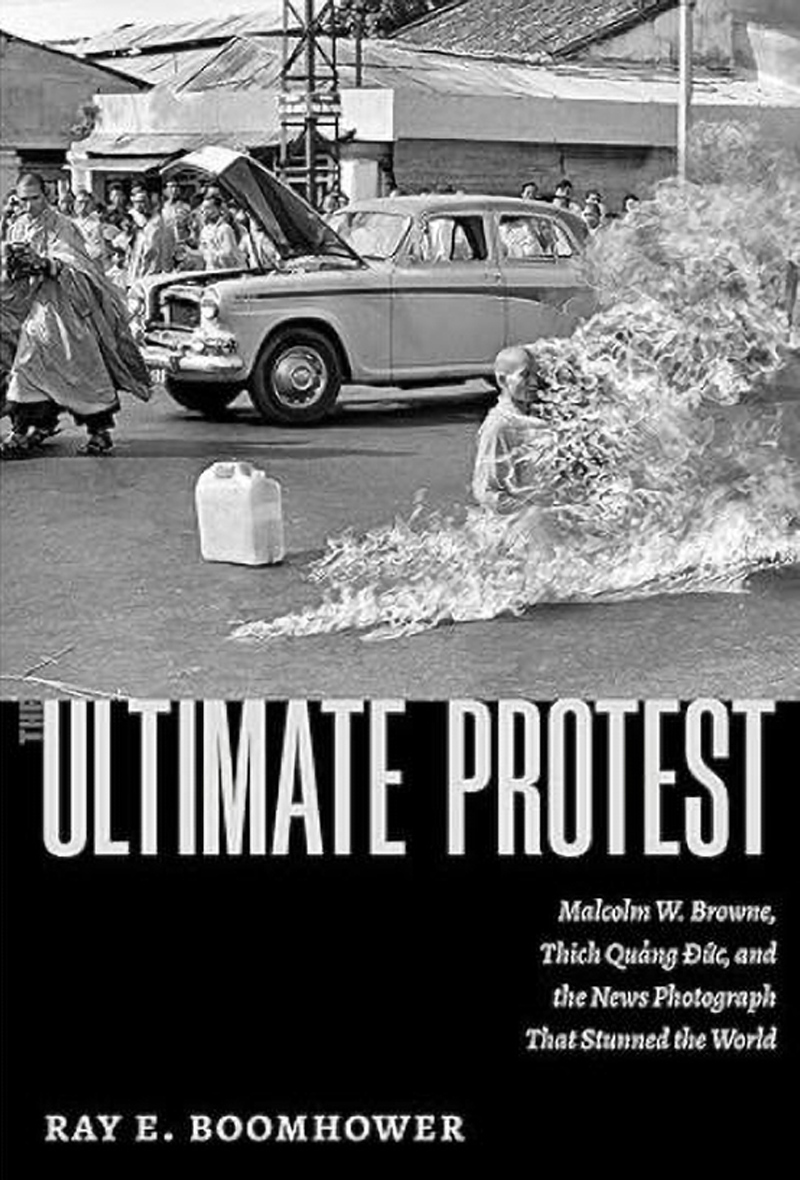

Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Thich Quang Duc, and the News Photograph That Stunned the World

By Ray E. Boomhower

High Road Books; Albuquerque

318 pages

Available in Hardcover & Kindle

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

When one thinks of the most iconic photos to come out of the American experience in Vietnam, three Pulitzer Prize-winning images shot by Associated Press photographers come to mind: Eddie Adams’ photo of Brig. Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting handcuffed Viet Cong cadre Nguyen Van Lem in the head at point blank range in Cho Lon, the Chinese quarter in Saigon; Nick Ut’s photo of nine-year Phan Thi Kim Phuc, running naked down the road after her Cao Dai village of Trang Bang had been napalmed by a South Vietnamese Air Force pilot; and Malcolm Browne’s photo of Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, immolating himself with a can of gasoline in the streets of Saigon as a protest to President Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime’s favoritism towards Catholics.

Now, the history of the latter photo, how it came about, the impact it had on the Vietnam War, and the world which viewed it, is thoroughly and superbly chronicled by Ray E. Boomhower, Indiana Historical Society Press editor, in his book Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Thich Quang Duc, and the News Photograph That Stunned the World.

How the Pulitzer Prize-winning image came to be is as intriguing as it is fascinating.

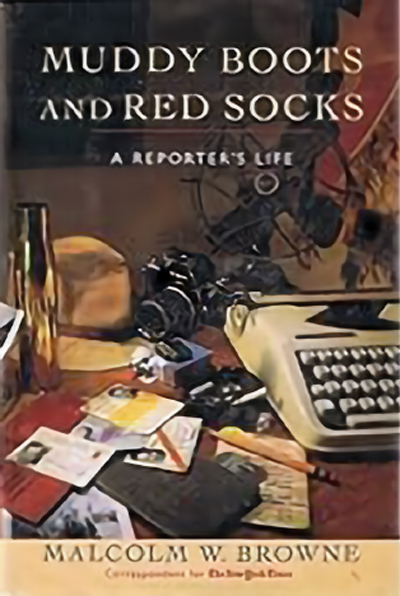

“The Buddhist monks had been conducting anti-government demonstrations for about a month and a half prior to this incident, demanding certain changes in what they regarded as kind of a pro-Catholic bias on the part of the government which made it difficult for Buddhists to hold high-ranking jobs and all that sort of thing. It was essentially a political protest movement rather than religious,” Browne told C-SPAN host Brian Lamb, who interviewed him regarding his autobiographical book Red Socks and Muddy Boots: A Reporters Life in 1993.

It is known that Buddhist monks reached out to the Saigon press corps, informing them that they were planning a spectacularly shocking event. A tactic they had employed before but without result. They telephoned foreign correspondents to warn them of it. However, their previous attempts at this type of PR before had rather rolled off the media’s collective back when it failed to materialize. The correspondents were bored by the tactic and paid it no mind. All except one: AP bureau chief Malcolm Browne. He was the only Western journalist that covered the fatal occurrence.

About that day, author Ray Boomhower writes, “Using an inexpensive Japanese brand Petri 35mm camera, he captured on film the self-immolation of a senior Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, while the monk sat calmly on a cushion in the traditional lotus position in the intersection of two busy streets in downtown Saigon.”

“I think it was one of the worst things I’ve ever seen,” Boomhower tells us Browne said after the horrifying incident.

“I don’t know exactly when he died because you couldn’t tell from his features or voice or anything. He never yelled out in pain. His face seemed to remain fairly calm until it was so blackened by the flames that you couldn’t make it out anymore. Finally, the monks decided he was dead and they brought up a coffin, an improvised wooden coffin,” Browne told Time magazine’s Patrick Witty in 2011 shortly before Browne’s own death in 2012 of complications from Parkinson’s Disease.

The image appeared on the front pages of newspapers all over the US and beyond.

“That picture put the Vietnam War on the front page more than anything else that happened before. That’s where the story stayed for the next 10 years or more,” Hal Buell, AP deputy photo editor in New York, told the author.

There were some news organizations that refused to run with the photo because they thought it was too awful an image. Among them, interestingly, was the New York Times.

“They never ran it,” Browne told C-SPAN’s Lamb.

The widespread media coverage of the photo of Thich Quang Duc made it impossible for it not to land on the Oval Office desk of President John F. Kennedy. Boomhower tells us that when President Kennedy called upon Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. to replace Frederick Nolting as the US Ambassador to South Vietnam, there was a copy of the photo on his desk.

“According to Browne, Lodge also informed him that when he met with Kennedy, the president had informed his new ambassador, `We’re going to have to do something about that [Diem] regime,’” Boomhower wrote.

And do something Kennedy did. In a CIA-orchestrated plot, which he allegedly sanctioned, on Nov. 2nd, 1963, both President Ngo Dinh Diem and his infamous brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, were assassinated in Cho Lon after being caught attempting to evade their assassins. JFK himself was assassinated 20 days later in Dallas.

It has been argued that Browne’s photo weighed heavy enough on the president’s mind that, in the very least, he looked the other way when the subject of a coup d’etat against Diem was broached in official quarters.

It has also been argued by many who served in Vietnam that photos like those of Browne, Adams, and Ut were what caused the US to, as is commonly thought, lose the war in Vietnam.

“At the time and for years later, Boomhower writes, “the Saigon correspondents were hounded by critics who blamed them for Diem’s downfall and America’s ultimate defeat and humiliation in Vietnam.”

Browne’s response to that charge was swift and pointed.

“This is just silly, of course,” Boomhower tells us Browne said. “To the extent that American newsmen `took sides’ in Vietnam or the Persian Gulf [which Browne also covered], it was on the side of the United States.”

And he added, “That did not mean that the journalists backed either the governments of South Vietnam or Saudi Arabia.”

Of Vietnam, he also admitted, “As American involvement in Vietnam wound down, it no longer seemed possible `to believe in the goodness or rightness of our cause.’”

And though he dismissed the notion that images such as his were responsible for the end result of the Vietnam War, according to Boomhower, Browne did admit, “Journalists inadvertently influence events they cover, and although the events are sometimes for the good, they can also be tragic.”

“Such tragedies, however, should make all journalists think twice about writing something that may leave blood on their hands,” Browne warned.

Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Thich Quang Duc, and the News Photograph That Stunned the World, is actually about much more than just the image. In the book, Ray Boomhower informs us of Browne’s own career in the US Army during the Korean War as a reporter for the US Military’s Stars and Stripes newspaper, and how that helped shape his years in Vietnam, a country whose culture he married into. It quotes extensively from Browne’s friends and colleagues who also covered the war. New York Times reporter David Halberstam, United Press International’s Neil Shehan, and the AP’s (and later CNN’s) Peter Arnett, come immediately to mind. It is a book worthy of taking an esteemed place on the shelves of every soldier who fought in the Vietnam War, every professor who teaches the war, and every student who studies it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment