Burying the Dead with Dishonor —

PART ONE

The charred remains of U.S. Huey helicopter shot down by Marxist FMLN rebels over El Salvador in January 1991. Two of the three crew members survived the crash but were brutally executed on the ground after their capture. (Photo: El Diario de Hoy — San Salvador)

By Greg Walker (ret)

USA Special Forces

Forward

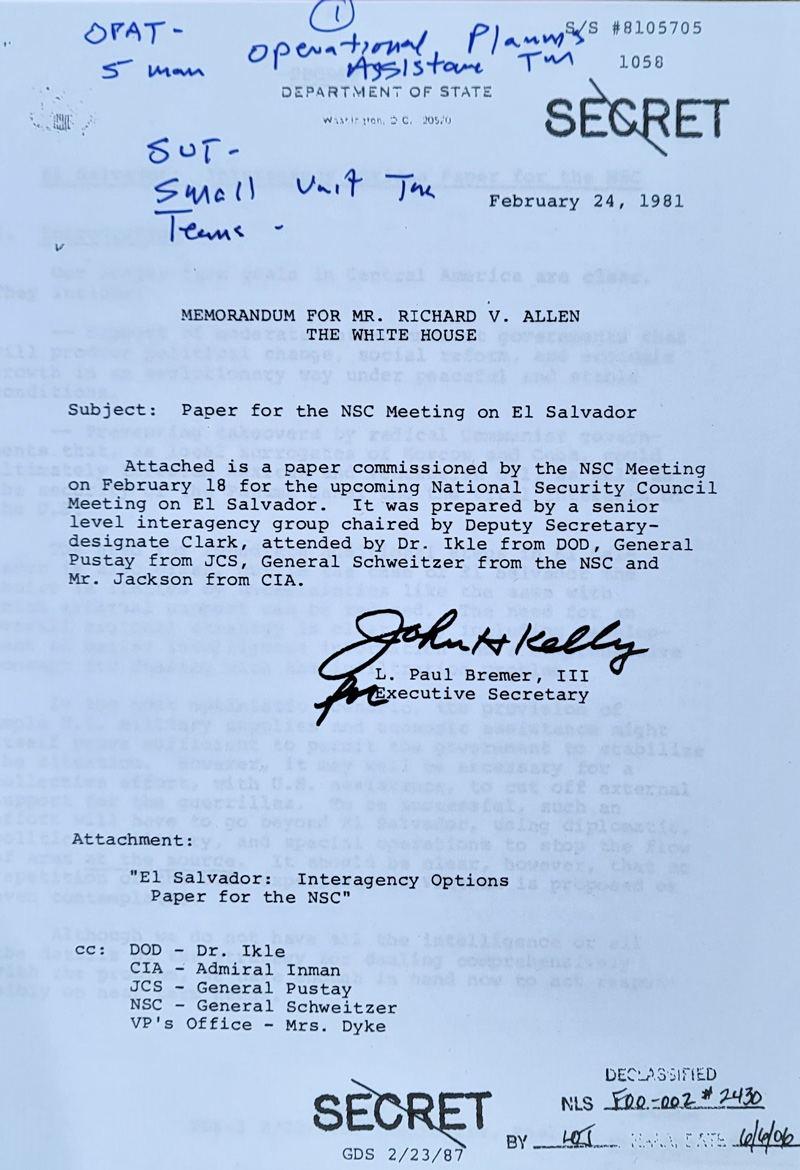

In late February 1981, then Executive Secretary to Mr. Richard V. Allen at the Reagan White House, L. Paul Bremmer III, submitted a working paper commissioned by the National Security Council regarding “The Way Ahead” regarding what would become the 10-year proxy war in El Salvador.

The meeting, held on February 18th, was chaired by the Deputy Secretary designate and attended by, among others, Dr. Ikle from the DoD, General Pustay (JCS), General Schweitzer (NSC), and Mr. Jackson (CIA). Its content would be declassified on June 6, 2006 (FOO-002-#2430).

This working paper would become the foundational document for the U.S. involvement in El Salvador. Its goal was to successfully circumvent the coming campaign from having to comply with the 1973 War Powers Resolution (P.L. 93-148). The WPR required that Congress be notified before U.S. Armed Forces could be introduced into hostilities or situations where imminent involvement in hostilities was clearly indicated by the circumstances, and that the President submit to Congress a report of such an introduction within 48-hours after such introduction of Forces had occurred.

“Firm rules of engagement would be required to prevent any blurring of the distinction between ‘trainer’ and ‘advisor.’ Nevertheless, inadvertent involvement would certainly still be a possibility…If U.S. [military] personnel to get caught up in direct hostilities, we might have to withdraw them or alternatively address the terms of the War Powers Resolution,” wrote Bremmer.

The interdepartmental group offered another distinct observation. “…the fall of the government of El Salvador would represent a major reversal for the United States. “We might have been able to maintain a posture of indifference toward the fate of that government had it not been for the large scale and blatant external support for the insurgents…particularly not in our own hemisphere, of permitting a government to fall because we have denied it legitimate means of self-help while the insurgents have received unlimited assistance from communist countries [Italics mine].”

The 1981 working paper specifically implied although it does not state that any and all combat engagements involving U.S. military personnel, particularly the Army’s Special Forces and their supporting elements, would be deliberately denied, covered up, and if needed the circumstances of both the wounding or killing of such personnel by either accident or enemy fire would have to be hidden from the Congress and American public.

This included “body washing” or creating a cover story as to how an American “trainer” may have died and where, and what he was doing at the time of his death. The 1981 working paper concludes with this statement. “In the present circumstances, the proposed deployment of MTTs (Mobile Training Teams) to regional commands in El Salvador does not appear to involve imminent risk of hostilities. However, such a deployment would increase the exposure of U.S. personnel to such a risk. In this regard, the U.S. personnel would be in close physical proximity to potential hostilities, and the company of Salvadoran personnel who might become engaged in hostilities. The War Powers Resolution defines an ‘introduction’ of U.S. Armed Forces as including the coordination or accompanying of foreign forces in hostile situations.”

In 1996, after a ten-year grassroots political campaign organized and executed by both active duty and retired Special Forces personnel who had served and fought in El Salvador, the Congress authorized the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal and appropriate combat awards and decorations for all those U.S. personnel, all Services, who participated in the war.

“Requiem for a Friend” — https://www.specialforces78.com/requiem-for-a-friend/

Shot down, captured, and executed

A tragic and violent incident on 2 January 1991 received increasing media attention as the facts surrounding the capture and execution of two U.S. Army aviators became known. Marxist guerrillas of the Farabundo Marti Liberation Front (FMLN) brought down a U.S. Huey assault helicopter with small-arms fire. The gunship carried two crewmen and Lieutenant Colonel David H. Pickett, commander of the 4th Battalion, 228th Aviation Regiment, based in Honduras. According to U.S. Army aviation crews who served in El Salvador at the time, FMLN guerrillas executed Pickett and his crew chief, PFC Ernest G. Dawson Jr., minutes after their helicopter auto-rotated down outside the little village of La Estancia.

While the UH-lH was airborne, ground fire wounded the senior pilot, Chief Warrant Officer Daniel S. Scott; he died of these wounds sometime during or after the crash. The ensuing killings occurred about 20km northeast of San Miguel, only several klicks from the Honduran border. Pickett and his crew were returning to Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras from a staff visit to American flight and ground crews stationed in El Salvador. Pursuing a shortcut route, the Huey had flown from San Miguel toward San Francisco Gotera, then moved north-east toward the town of Corinto. By this approach they could reduce flight time and slip inside the established “Green Three” route into Honduras, leading directly to Soto Cano.

“The doctor who performed the autopsies had access to the debriefing. He told us it appeared the crew chief was shot first,” recalled a CWO 2 “Bob Bailey.” “Pickett apparently made the decision to run for it and was peppered with AK-47 fire at close range.” (Author’s Note: Some U.S. Salvador veteran aviation crewmen providing information on this and related incidents requested anonymity for security reasons; where noted, such sources are identified here by noms de guerre).

An aviation accident investigation team from Fort Rucker, Alabama, flew to El Salvador to evaluate the incident, per Army regulations. According to “Bailey,” this team’s report “was never released to the aircrews in El Salvador. This was fairly unusual, as all crash reports are circulated among the pilots so we can learn why a crash took place.”

Pickett’s helicopter had been armed with two M60 machine guns, but these were strapped to its floor rather than mounted. At the time, policy for airframes flying in Honduras called for positioning the guns in this manner.

It was after this incident that authorities determined a need for an ongoing airborne support unit in El Salvador, and it fell to B Company of the 4th Battalion, 228th Aviation Regiment, to provide such an asset even as the war was beginning to be brought to a diplomatic conclusion.

Aircrew from B Company, 4/228th. relaxing between missions. Calling themselves “Danger Pigs, …these crews flew countless taskings in support of the Salvadoran war effort. UH-1H choppers were known by their crews as “pigs” (a loving term). Here door gunner Cory Brua holds AN/PVS-6 night-vision goggles mounted on his flight helmet. Such gear permitted U.S. night operations whereas, at the time, Salvadoran air crews did not have such equipment. (Courtesy Greg Walker)

“They wanted to cover it up,” confirmed one flyer, known here as CWO 1 “Jim Miller,” “But it was definitely shot down.” It was commonly known among those serving in-country that Pickett’s aircraft had taken ground fire from a confirmed concentration of FMLN forces and indeed had crashed almost on top of the guerrillas after being hit. After the tragedy, Army aviation crews began flying in tandem to cover and, if necessary, recover one another if forced or shot down during flight. All American helos flying in El Salvador were ordered to fly with mounted guns carrying live rounds in the chambers; B Company, 4/228th, was selected to provide air and ground crews in support of the U.S. MilGroup operations in El Salvador.

Door gunners from the 193rd Infantry Brigade in Panama were assigned to B Company in force after the executions. Air crews from B Company flew the body-recovery mission to Pickett’s crash site, where they came under intense ground fire from FMLN guerrillas; the U.S. gunners returned fire and completed their mission. It was found that Pfc. Dawson, promoted to SP4 after his death, was killed with a single bullet to the back of his head. Pickett had witnessed this murder and attempted to escape. The autopsy report states the colonel was hit with some 15 to 20 rounds, including at least one which passed through his hand and then struck his face.

According to “Bailey,” who spoke with the doctor conducting Pickett’s autopsy, the conclusion was that the colonel tried to cover his face with his hand even as guerrillas fired point-blank at him. After the deaths of Pickett, Dawson and Scott, the 4/228th renamed several facilities at Soto Cano for the dead aviators. For example, the former Camp Blackjack (home to the 228th) is now known as Camp Pickett.

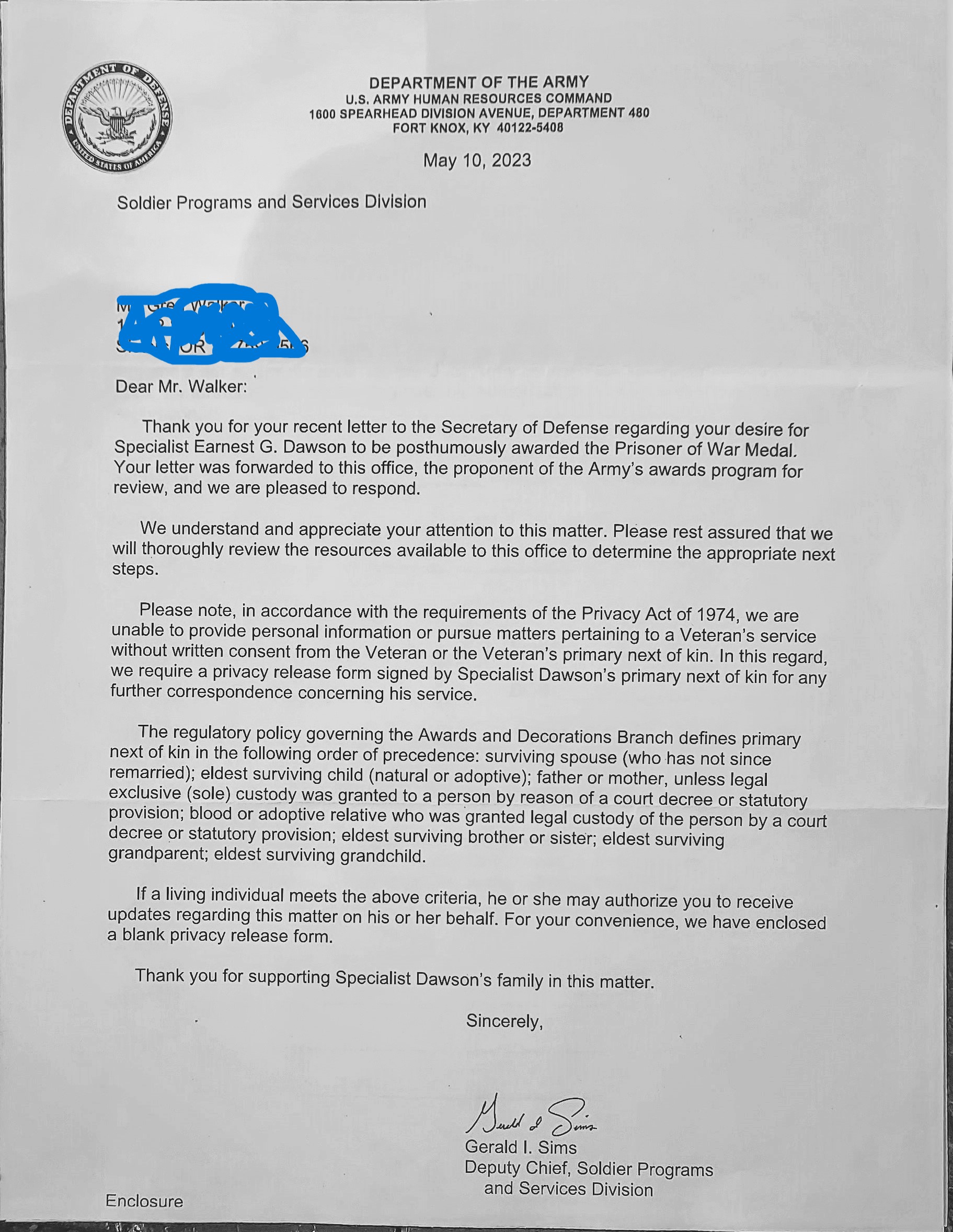

Today, Colonel Pickett’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery overlooks the El Salvador memorial in Section 12. His father, after a hard-fought battle with the Army, was successful in seeing a posthumous POW medal awarded in his son’s memory. Recent developments in May 2023 between the Secretary of Defense’s Office and the Human Resources Command at Fort Knox see renewed effort being made, at Secretary Lloyd Austin’s express direction, to review and facilitate the same award for Earnest Dawson.

SP4 Dawson’s surviving family members were quietly pleased to learn of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s direct involvement to see their loved one’s sacrifice finally acknowledged with a posthumous Prisoner of War medal. (Courtesy Greg Walker)

July 15, 1987 — More lies as families grieve

On 15 July 1987, a UH-1H helicopter under the operational control of the U.S. MilGRP, crashed while attempting to return to Illopongo after aborting a MEDEVAC mission. According to the crash report filed at Fort Rucker, Alabama, pilot errors and poor weather during its attempted landing were at fault.

At 80-plus knots the UH-1H crashed into the hillside above Lake llopango and some fifty meters below the ridgeline. Onboard were two Special Forces medics enroute to the National Training Center (CEMFA) in La Union. Gunfire there had severely wounded SSG Tim Hodge, an SF adviser in the neck; and he required immediate evacuation.

The aircraft and its crew were assigned to Joint Task Force Bravo, stationed at the Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras. However, the air crew was assigned to support operations in El Salvador and was based at Illopango Air Base. Task Force Bravo predated the 228th Aviation Regiment’s service in El Salvador. Originally many in El Salvador believed the aircraft had been struck by an FMLN shoulder-fired, Soviet-made SA-7 or SA-14 antiaircraft missile. However, pilot error was stated as the cause of the crash by the investigative team from Fort Rucker. Today, that conclusion rings hollow based on newly discovered information.

Six Americans were reported killed in the crash: Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Lujan, a decorated Special Forces officer and the OPAT for CEMFA in La Union; Lt. Col. James Basile, deputy commander of U.S. MilGrp El Salvador; First Lieutenant Gregory Paredes, the co-pilot; Chief Warrant Officer John Raybon, a pilot whose resume included flying for the DELTA counter terrorism unit as an aviator with the “Night Stalkers”; the crew chief, PFC Douglas Adams; and SF medic, Sergeant First Class Lynn Keen. SFC Tom Grace, also a medic, was the sole survivor.

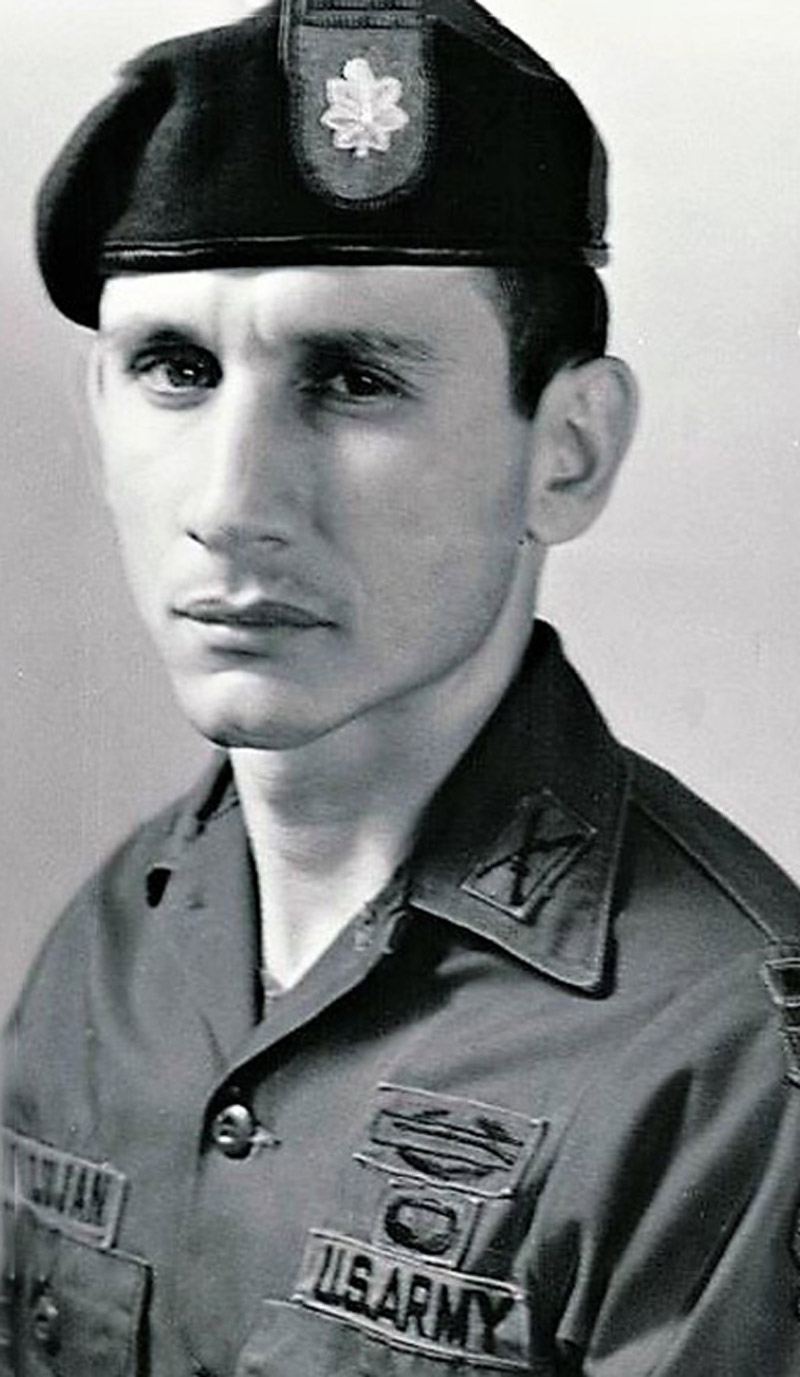

(Photo courtesy Ms. Judy Lujan)

Circumstances of the crash were immediately hushed up

The only survivor, severely injured, was SFC Thomas Grace. Both Keen and Grace worked at the National Military Hospital in San Salvador where they assisted in treating wounded Salvadoran soldiers. Keen was posthumously awarded a Meritorious Service Medal (MSM), the peacetime equivalent of the Bronze Star. Keen’s award was a continuation of the flawed awards policy dictated by the USGOV after Sgt. 1st Class Greg Fronius was killed in action in March 1987. Fronius died rallying Salvadoran troops under attack at the 4th Brigade’ s headquarters at El Paraiso. The “Green Beret” sergeant was confronted by three FMLN sappers who shot him, and then murdered him by placing an explosive charge under his body and then detonating it.

Sixty-four ESAF troops were killed during this attack, with another seventy-nine wounded; only seven guerrillas were reported killed. Fronius is credited with stalling the enemy assault, as guerrillas overran the compound after ESAF officers abandoned their troops. His team leader, now retired Gus Taylor, recommended Fronius for a posthumous Silver Star; the proposal was bitterly fought over in Panama and at the Pentagon. In the end, Fronius was awarded a posthumous MSM and a Purple Heart with 3 U.S. general officers signing off that “no mention is to be made of combat” regarding Fronius’ death.

This represented the awards policy hinted at in 1981 in Bremmer’s classified working paper. It was a policy that became the norm and applied to U.S. military personnel fighting and dying in El Salvador, a policy shrouded in shame, deceit, and dishonor.

What truly happened at CEMFA / La Union and at Lake Illopango

In March of 2023, this author began revisiting the circumstances of the shooting of Special Forces adviser, SSG Timothy Hodge, in La Union that prompted the U.S. helicopter piloted by Chief Raybon and Parades to be launched from San Salvador, and the subsequent abortion of that mission and deadly crash.

That investigation continues. However, the Fort Rucker accident investigation FOIA has already been fulfilled and a growing number of the family members of those lost as well as others who until now have remained silent, are for the first time being shared in this initial story for the Sentinel.

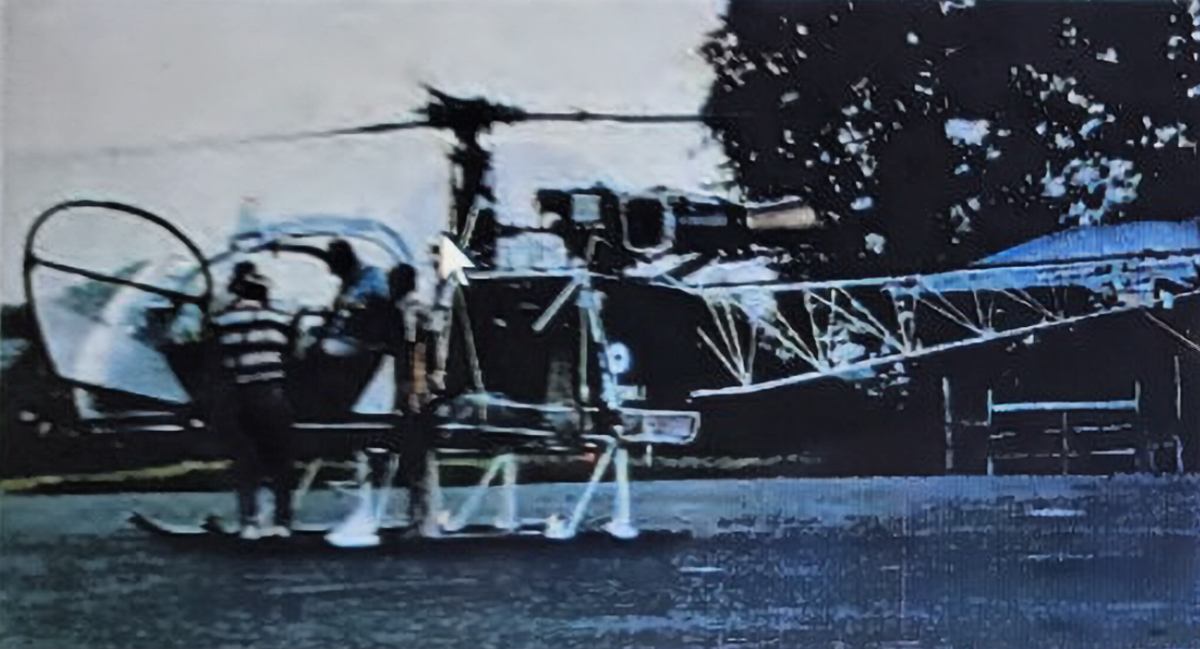

Army aviation-support personnel at Illopongo Air Base change the engine after a precautionary landing near Limpa River by a U.S. helo. These personnel kept U.S. assault helicopters flying, despite hits from enemy small arms and everyday mechanical problems. (Courtesy Greg Walker)

Salvadoran “Llama” prepares to lift fully armed SF advisers into Chalatenango area, long considered a guerrilla stronghold. This photo was taken in 1980.(Courtesy Greg Walker)

And the information received to date is disturbing when compared to the official reports and media releases at the time. Examples of this include:

- LTC Joseph Lujan had accepted an offer made in Washington, DC, to serve a one-year tour of duty in El Salvador as the OPAT for the National Training Center in La Union. In a phone call to his wife shortly after that meeting, and perhaps with a premonition, he told her “I’ve just made the worst decision of my life.”

- In the official accident report issued by Fort Rucker it is states the U.S. helo aborted its medevac mission 12 minutes after departing the LZ at 1st Brigade in San Salvador. This due to extremely bad weather. The report offers this did not affect the MEDEVAC of Tim Hodge as a Salvadoran helo had launched from San Miguel, just a 20-minute flight away from La Union / CEMFA and was already transporting the wounded soldier to the military hospital in San Miguel. However, it has now been learned the initial request for a Salvadoran MEDEVAC was rejected in San Miguel with the comment “We don’t fly at night.” According to retired Special Forces medic Morgan Gandy, who provided combat life-saving care to Hodge at CEMFA, the UH-1H that came from San Miguel was clearly a CIA aircraft with U.S. crew onboard.

- Ms. Judy Lujan, LTC Lujan’s widow, filed a complaint with CID at Fort Bliss, Texas, as she was not convinced her husband’s remains had indeed been recovered as reported to her. A CID agent there called her back and offered LTC Lujan’s remains had been properly identified at Gorgas Army Hospital in Panama. When she asked how they were identified she was told “by his medical and dental records.” Ms. Lujan informed the agent that was impossible. When asked why, she replied “I have his medical and dental records here!” The next day CID was at her door demanding the records from her. They had been sent to her by a point of contact in El Salvador her husband had left for her to call in case he was killed or disappeared. Along with the records she received his green beret, and a pair of his dog tags with blood stains on them.

LTC Lujan’s family was told his remains could not be viewed as they were burned beyond recognition. However, the Fort Rucker report and several pictures purported to be of the helo’s wreckage, said to have been located on the hillside into which it crashed, clearly show the fuselage did not burn. The trees and ground are not burned. And the diagram purported to show where each body was found is likewise not described as having been burned. The aircraft flew directly into the hillside at such speed that, per the Rucker report, ALL those onboard but one were thrown from the aircraft, their safety harnesses and belts tore away due to the force of the Huey’s impact.

A close friend of Chief Raybon and former crew chief likewise shared that Raybon’s remains were likewise labeled as non-viewable.

Even more puzzling is an Aviation Safety report identifying another UH-IH, the wreckage of its tail boom and rotor along with the aircraft’s ID number clearly visible, having crashed on the same date and year as the helo LTC Lujan was on…its wreckage in water at Lake Illopango. As of late May 2023, the Command at Fort Rucker offers it has and knows nothing about this second helicopter.

Another highly credible source, an American who served in El Salvador and as an Agency employee, former Marine Force Recon (Vietnam) veteran, Mr. Harry Claflin, shared with this author that as of 1992, when he finally left El Salvador, the fuselage and those onboard who were killed had not been recovered from Lake Illopango. Is Claflin referring to the mystery helicopter Fort Rucker knows nothing about? Claflin, who trained and led the highly effective GOE, or Special Operations Group, as well as the Salvadoran Airborne Battalion, is quite familiar with the National Training Center in La Union.

“I was at CEMFA after the attack there. I was on the immediate reaction team. It was always on alert. It can be launched in less than 20 minutes. I was in the battalion commander’s chopper. We went after the G’s that were running up the railroad track. They were headed for the hills.

“In the late 80’s there were so many things going on at Illopango it was not possible to know everything and I had my plate full with the GOE training at the different Brigades. Some of what was going on was best not to know anything about. I tried to stay away from Hangar Five and what the ES Airforce S-2 was up to. Sometimes you can know too much and wind up dead. After spending ten years being on the inside I found it was not healthy to get involved with some things. I was at the DAO’s house one evening to celebrate a new class of cadets that had just graduated and General Bustillo [the Salvadoran Air Force commander] saw me there. The next day he called me into his office and told me to remember where I worked and lived and not get too close to the Americans.”

Claflin, the only American to have been commissioned as an officer in the Salvadoran military (as a captain), was busy in 1987.

“During that time frame the only person I worked with was Mark Cardwell who was my direct contact with the Agency. 87 was a busy year for me with a lot of catch-up work from being in Nicaragua for 8 months, 4 in the North training CONTRA and 4 months in the South training the FDN. My world was very compact and I did not pay a lot of attention as to what other units did or did not do. I went to the monthly meeting that MilGrp held at the embassy in San Salvador…to stay in the loop… As you know the Agency had a base of operations on an island off the coast of El Salvador [Tiger Island]. If the Agency was involved you will never find out what happened for sure.”

Setting the record straight – No fallen comrade left behind

In 1998, SFC Greg Fronius’ family received their loved one’s posthumous Silver Star at the largest awards and decorations ceremony held at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for the 7th Special Forces Group, since the Vietnam war. Additional long-overdue combat awards were made to include fifty Combat Infantry and Combat Medical badges. This the result of the 10-year grassroots political campaign to see the U.S. Congress reverse historical course on the subject and authorize our war in El Salvador as an official U.S. military campaign.

Using the information gathered by those of us involved in that campaign, LTC David Pickett’s father, himself a retired Army colonel, was later able to force the Army to recognize and then authorize his son’s posthumous POW medal. A similar effort by SP4 Dawson’s family, which did not have the kind of horsepower and knowledge of the system as Pickett’s father did, has to date not seen the same just due awarded their son. In early April of this year a concise documentation packet petitioning Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III was sent to the SECDEF – asking he and his staff to review this case and to step in and correct this grotesque manipulation of this 20-year-old black service member’s ultimate sacrifice.

In 1996, Ms. Judy Lujan, escorted by the sole survivor of the crash that killed her husband and 6 others, attended the dedication of a memorial to those Americans and Salvadorans killed during the war in El Salvador at Arlington National Cemetery. When interviewed by the Washington Post she said this. “Judy Lujan, wife of Army Lt. Col. Joseph H. Lujan, was told her husband died in 1987 when the helicopter carrying him crashed into a hillside during stormy weather. But the Army never produced her husband’s personal effects or photographs of his corpse, despite her repeated requests, she said yesterday. “I can’t get on with my life, I can’t do anything, until I know for sure he’s dead,” she stated.

Arlington National Cemetery Memorial Ceremony —

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3uy8Ey23Is&t=5s

When I asked Ms. Lujan if she has ever received her husband’s personal effects…his watch, his wedding ring…she replied she has not. “I was told, when I asked for these, that they had been ‘washed down the drain’ during her husband’s alleged autopsy in Panama.

Judy Lujan has never remarried.

A warning from our past

“The nation which forgets its defenders will be itself forgotten.”

Calvin Coolidge, 1920.

IN THE SEPTEMBER ISSUE OF THE SENTINEL–

The never before released details of the wounding of SSG Timothy Hodge, A Company, 3/7th Special Forces Group (ABN), in his own words — and the true account of how 6 Americans lost their lives in their attempt to save him.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Greg Walker is an honorably retired “Green Beret.” Along with Colonel John McMullen he founded the Veterans of Special Operations — El Salvador in 1989. https://www.specialforces78.com/requiem-for-a-friend/

A veteran of the war in El Salvador and Operation Iraqi Freedom, Greg’s awards and decorations include the Legion of Merit, 2 awards of the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Special Forces Tab, 2 awards of the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal, and most recently the National Infantry Association’s Order of Saint Maurice.

Mr. Walker is a Life member of the SFA and SOA.

Today Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

The author in La Union, El Salvador, 1984. (Courtesy Greg Walker)

Looking forward to part-two. Are you thinking of expanding this into a book on this time in Special Forces history?

Steve

Steve – In 1994 I wrote “At the Hurricane’s Eye – U.S. Special Operations Forces from Vietnam to Desert Storm”. I included a chapter on El Salvador and have written quite a bit on the subject since. I don’t see myself authoring a specific book along the lines that you mentioned – I’m content with being able to present stories such as this one in the Sentinel but I appreciate your kind thought.

I would only add that the two-part series’ title refers to the policy set in Washington DC at the onset of the war. On the ground there are countless examples of courage, ethical behavior, and honor on the part of the vast majority of the U.S. advisers. In DC, however, there are far too many examples of just the opposite when it came to our injured, wounded, and KIA.

DOL!

Thank you for clearing up many questions that have lingered with your stories. I was on a team with Baez in 1974-1976. Also was on a team with Raybon (1/10th) 1978 before he went to flight school. Did you ever encounter Johnnie G. Santora?

Thank you, Melvin – I knew Johnny Santoro when we were at 3/7 together He and CPT Gil Nelson were both friends. That CW Edwards survived that crash despite serious, career ending injuries was a blessing. I was in ES, in La Union, when we got word of the crash. CW said in a letter written long ago that it took 17 hours for the rescue/recovery effort to make its way to the crash site. Both Johnny and Gil were stellar Special Forces soldiers and their loss was felt throughout 7th Group. DOL!

Dear Greg,

Thank you for writing this article. I lived with SSG Timothy Hodge for 4,years, from 201 to 2014, as a caretaker, he got married then and we moved on to different lives.. I have never met a man with such a positive attitude and a love for life DESPITE his condition. we became great friends and still talk on a weekly basis. The 1 thing that always made me appreciate his life in the army was that he never talked of the event that prompted his wounding. He lived up to the NDAs that he signed. Finally, just yesterday he was able to talk about it. I am so proud of Tim, and now others will be also. Because of your article and hard work SSG Hodge, and others will receive the recognition they deserve. God Bless you and the others who participated in this work and uncovered the truth. Thank you.

There was honor, not dishonor, on the night of July 15, 1987, in El Salvador.

I was the Brigade Advisor for the 3rd Military Zone, San Miguel, El Salvador, the night six US soldiers died in the UH1H helo crash.

When SSG Hodge was wounded at the CEMFA (National Training Center) in La Union, the Team SGT called me for a Salvadoran Army medevac helicopter. The Salvadorans had three UH1Hs in San Miguel, 18 miles from La Union. We were the closest aviation assets available. As I ran to the Salvadoran Operations Center, I saw the Salvadoran helicopter already lifting off for La Union to get SSG Hodge.

The Salvadoran helo brought SSG Hodge to the San Miguel Regional Military Hospital. The hospital was 200 meters down the hill from me. I met the medevac helo as it landed.

The San Miguel Regional Military Hospital was the best option for SSG Hodge. The hospital had competent and experienced trauma care. During this period of the war, the Salvadoran Army suffered eight casualties a day, mostly due to mines and booby traps. There were two 7th Special Forces Group 18D’s permanently assigned to the hospital operating room on 45-day rotations.

A helo flight to San Salvador, on the other hand, would not have been prudent. San Salvador, the capital, was 50 miles from La Union. SSG Hodge was in critical condition, and those extra minutes saved by landing in San Miguel were crucial. The month of July is the rainy season in El Salvador, and there was cloud cover that evening. The Salvadoran pilots had no guarantee of making it to San Salvador.

There were eight 7th Special Forces soldiers with SSG Hodge in the San Miguel Hospital for that night and into the next morning. That included my three-man team, the two 18Ds, and three of SSG Hodge’s CEMFA teammates that accompanied him from La Union on the helo medevac.

I was on the phone that night, an open line, with MILGP US Embassy as they activated the MILGP UH1H medevac from San Salvador.

Dr. Romero, Director of the San Miguel Regional Hospital, said, “Don’t send your helo. SSG Hodge must be stabilized. If you try to move him now, he will die. He won’t be stabilized before tomorrow morning.”

MILGP said, “LTC Basile (MILGP XO) is coming anyway. He wants to get the US helo into position. Make a pot of coffee. The crew will sleep in the extra bunks in your intel center. They’ll be on standby. The minute the doctors give them the green light, they’ll move SSG Hodge to higher-level care. ”

CW2 John D. Raybon, a former Special Forces NCO, volunteered for the mission, “I am piloting this flight,” he said. “That is one of our guys.” A few minutes after CW2 Raybon lifted off from San Salvador, he got caught in the clouds and crashed into the Cerro de las Pavas, below Cojutepeque.

SSG Tom Grace, 18D, survived the crash. The other six crew members and passengers perished.

SGM Grace was my 3/7 Battalion S-3 SGM from 1994-96. He later became CSM, 3/7 SFGA.

Grace said, “I was the junior passenger on the helo that night. That’s why I got stuck in the hell hole, the wind tunnel. But that seat saved my life. The last thing I remembered was entering the clouds. We couldn’t see our hand in front of our face.”

The next morning, JTF Bravo, Soto Cano, Honduras, sent their medevac helo and surgical team to the San Miguel Hospital to evacuate SSG Hodge. The Soto Cano US Army surgeon said, “The Salvadoran doctors and the 18Ds did superb work.”

After the Soto Cano helo lifted off, the 15 Salvadoran officers assigned to San Miguel stopped me during the day to express their condolences for the loss of six US soldiers in the helo crash. They said, “Two LTCs got on a helicopter in the middle of the night in San Salvador to come to the rescue of one of their soldiers. There is no army like the US Army.”

COL (R) Kevin M. Higgins

San Vicente, El Salvador (Oct 83-August 84)

San Miguel, El Salvador (Sep 86-March 88)

Good to hear follow up from Col. Higgins. I served with Kevin in San Miguel and I would attest his recounting of events is 100% accurate. Thank you, sir. DOL

I served with Kevin at 3/7 to include a composite MTT to Brazil. Since his post we have reconnected and he has provided me with invaluable first-hand information about what was occurring at San Miguel that night to include the actual identify of the FAS MEDEVAC – Part Two will reflect Colonel Higgins’ input, information that is not available in the crash report from Fort Rucker. My sincere appreciation is extended to Kevin for sharing his recollections of that night – to include these being further shared with SSG (ret) Tim Hodge, who was wounded at CEMFA that night and until just recently was not fully informed of all that took place. This in order to see him successfully moved from El Salvador to the States and into treatment / recovery. Tim remains paralyzed by his injuries but has an incredibly positive attitude and perspective on what took place and his life today – an awards packet is being prepared to include a cover letter from Major General (ret) Kenneth Bowra in support of a long overdue Purple Heart, CIB, and AFEM for his service in El Salvador. DOL!

As the former 3rd Military Zone SFO&I Advisor in San Miguel during the tragic events related to Tim Hodge’s shooting in CEMFA which led to the fateful helicopter crash in Ilopango, I would like to present an additional point of view in hopes of adding clarity to aid to the accuracy of the report.

I fully endorse Col Higgin’s input, and most particularly the opening sentence that vividly reflects the aura surrounding all tragic events described in Greg’s article. There was honor then, and there is honor today in the fact that Col Picket is buried at the Arlington National Cemetery. There is honor in the fact that, despite the real need to have national policies designed to attain plausible denial-ability, or to work within legal frames, thanks to the relentless and valiant campaign by Col McMullen, Greg and others; a great number of ES veterans received due recognition for their services and sacrifice; and were awarded CIBs, CMBs, Expeditionary Medals, purple hearts, and the posthumous Silver Star for SSG Fronius.

Articles and books have been written on the above related subjects; however, special credits must be given to Greg for his research, investigation, and reporting. While these reports always bring memories of our fallen brothers; many, like me, sat on the sidelines during his team’s selfless pursuit for honor. Greg and those allies built their cases for their noble cause of recognition using much of that information. While I never expected anything in return for the time I spent there, thanks to their relentless hunt for righteousness, I was awarded a CIB (first award), the Defense Meritorious Service Medal (DMSM) and even retrospectively following retirement, I was awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) without the usual removal of the DMSM.

Regarding Tim Hodges MEDEVAC mission from CEMFA, and the Ilopango Huey crash, as the eternal SFO&I Seargent seeking truth and accuracy in the reporting, to dispel ambiguities or innuendos related to a potential CIA involvement in San Miguel and Ilopango; and while applying that what Gen Boykin always says, “never believe the first report”, I offer additional sources of information and point to some facts for consideration.

As the SFO&I Advisor to the 3rd Military Zone on site that tragic night, like Col Higgins and Dan Wheeles, I verify it was a 3RD BDE chopper that went to CEMFA and took Hodges to the Military Hospital.

Regarding the helicopter crash at Ilopango, and while I greatly respected the audacity of the victims for trying to get to San Miguel at night during bad weather, from the moment I became aware that the Huey had crashed into the mountain, I said to myself that the decision taken to lift-off was hasty and was tragic. Unfortunately, it led to the loss of six brave lives. Had they waited just a few hours until the morning, taking into consideration Dr Romero’s advice, we wouldn’t be writing these notes today. The fallen brethren were rightly following their hearts to not to leave another brother behind.

The caption in one report’s photo indicates that the “Huey’s engine was operating at maximum power” and implies ‘possible’ involvement of another aircraft stating: “This indicates a possible evasive effort to avoid a now known second UH-1H, possibly being flown by CIA contractors, departing the air base under extreme weather conditions.”

Working as the RIC Advisor in San Miguel at the time, we consumed all sources of information available from ESAF, MILGROUP and Embassy Station associates; and this is the first time I heard a rumor of the possible involvement of two CIA helicopters; one during the MEDAVC from CEMFA and another near a mid-air collision in Ilopango. All of the evidence pointed directly to weather conditions.

Prior to me going SF, I had extensive knowledge in helicopter flying from 1968 to 1974; both in civilian and military life. I was then a Crew Chief/Mechanic with a Primary MOS 67N (Bell UH-1H Iroquois – Bell 204) and a Secondary MOS 67V (Bell OH-58 Kiowa – Bell 206 Jet Ranger). By 1969 I had learned to fly and flew choppers many times as a co-pilot during test flights. During my time as a flyer, I assisted in the investigation of two Huey crashes due to inclement weather conditions in the Peruvian jungles, the crash of one Jet Ranger due to a turbine factory defect, and one crash due to pilot error while attempting to auto-rotate landing. In addition, in 1975, while attending Jungle Training in Panama as member of the 82nd Abn Division, black storm clouds engulfed the Huey we were in and “pushed’ our flight course for almost 20 miles, ultimately forcing us into a hazardous landing in a very small patch that appeared in the middle of the jungle. That day I took my infantryman’s gear off and assisted the young E-4 crewmember to inspect the bird for damage, flight worthiness and operability. With that background, I submit for consideration the additional factors that could most likely have contributed to the Ilopango crash. These may also aid to explain the engine’s maximum power final operating conditions:

• Flying near mountain ranges, or near a mountain slope is particularly dangerous due to the potential for down-slope winds that can generate up to 40 MPH wind gusts and/or vortex and/or moderate to severe turbulence close to the ridge top level. As well, there is the likelihood of very strong updrafts and downdrafts.

• Flying at night in bad weather, with seven passengers, carries a greater risk than flying during daylight hours and in good weather.

• Night flight over unlit terrain without a visible horizon and with incompatible weather conditions for a night visual flight rules (VFR) is one of the classic helicopter crash scenarios.

• 1980’s NVG – Night Vision Goggles when used, altered a pilot’s depth perception, requiring extensive training and certification, and generally was not recommended during stormy weather conditions.

• The horizon is hard to discern during night flight due to the darkness of the terrain, ground lights patterns, or lack of them thereof. Visual flight rules (VFR) flights require maintaining visual references with the surface. Instrument flying was not available. When there is lack of instrument flying or referential beacons, orientation at night is normally maintained by celestial (moon) or artificial lighting (lights on the ground). None were available.

• With an overcast sky or no moon, and without sufficient lighting, the horizon becomes invisible, and it impossible to visually maintain level control of the helicopter.

• Flying at night in bad weather with near zero visibility will lead to a loss of sense of horizon due to the darkness of night, storm clouds and blinding rain; and quickly evolve into an extremely dangerous flight condition.

Some of the factors listed above combined that day. One of the most dangerous flight conditions is the lack of visibility with a loss of horizon. This clearly was present as Col Higgins points out that CSM Grace had said that “the last thing I remembered was entering the clouds. We couldn’t see our hand in front of our face.” The combination of those conditions makes it plausible that the pilot had to apply full throttle to get more RPMs while trying to increase collective (pitch); either to gain lift and more altitude, or to increase maneuverability. However, when one applies maximum power, it also increases torque. Pitch and torque coupled to the darkness of night and storm cloudy conditions, and flying next to a mountain slope, very likely without horizon visibility, it rapidly evolve into the most extreme dangerous flight condition. That could only have led to the pilot’s total disorientation while he was trying to determine where he was heading; up, down, left, right, away or into the mountain.

Similar conditions appeared to have happened to Kobe Bryant’s helicopter pilot, even as he was flying during daylight hours. A press report on the findings of the accident indicated that “the pilot made a series of poor decisions that led him to fly blindly into a wall of clouds where he became so disoriented, he thought he was climbing when the craft was plunging toward a Southern California hillside, federal safety officials said.”

Regarding the downing of the Huey by the guerrillas in San Miguel in 1991, the specific crash location was at Loma El Recodo, Canton de San Francisco, Municipaly of Lolotique, San Miguel Department; approximately 15 km northwest of San Miguel.

Witnesses declaring before a Judge in Chinameca during the trial of two former G’s accused of murder, ping the precise locations and timeline of the events. Witnesses declared that some local peasants approached the downed aircraft first and tried to save the survivors. They stated that two of the crewmen were injured but alive, and that in broken language they asked for water and to be moved carefully due to suffering pain from their injuries. Witnesses also declared that when the guerrilla unit arrived to the crash site they cleared the area, and that the flyers were executed before water was delivered to them.

I have a word document with copies of local newspaper articles that include pictures and the trial deposition transcripts if you are interested.

Regarding the fact that some of the victims’ relatives did not get see the bodies of their deceased, I submit that those relatives will never understand the extent to which a corpse gets destroyed with a grenade, mortar fire or a helicopter crash into a mountain. Mangled corpses become pulp mass quickly and have a much faster decay rate than non-accidental deaths. I’ve seen my share of mangled bodies; and for that reason, I will never understand why someone may want to see a badly mangled body that he or she may not be able to recognize.

MSG (Ret) Juan Calderon

Juan – thank you for your very detailed recollection. Yours and Kevin’s fills in an important gap in this story as what took place in San Miguel is not mentioned in such detail in the Fort Rucker crash report, nor elsewhere. Morgan Gandy, the SF medic who helped save Tim Hodge’s life that night, felt the MEDEVAC was an Agency Huey in the “fog of war” circumstances present that night. He now knows it was indeed an ESAF bird/crew and thanks to Kevin and I communicating further, we now know how the ESAF MEDEVAC/Extraction system was set up, how many birds were at San Miguel and where located, and how many at Illopango. All of this will be reflected in Part 2. Some additional news – Major General (ret) Ken Bowra has authored a Letter of Recommendation for the Correction of Military Record regarding Tim Hodge. The packet is a strong one with elements of the documentation Colonel John McMullen and I, along with others, assembled so many years ago now. With good fortune Tim will finally see the award of the CIB, Purple Heart, and AFEM for his service and sacrifice in ES. Again, thank you for reaching out and sharing as you have – it is sincerely appreciated and so very important. DOL!

Greg, great write-up on LTC Pickett’s, CWO Dan Scott’s, and PFC Dawson’s death. I served with those men from August ’90 to Christmas Eve ’90. DUSTOFF crews were attached (TDY) from stateside MEDEVAC units for 4-6 months at a time. My crews (3) self-deployed from Fort Carson, CO to Soto Cano AB. I was the 571st Det (Fwd) Det SGT for the deployment. A couple weeks after we left, the men were shot down and killed. I have a bit of a conspiracy theory regarding the incident. It would be better discussed by personal email. Warmest regards. David J. Litteral CSM (R).

SSG (ret) Tim Hodge, wounded and left paralyzed in 1987 while serving in El Salvador, has been sent the comments by Kevin Higgins and Juan Calderon. He is most thankful for them as they fill in what have to date been blanks in what happened after he was loaded on the ESAF MEDEVAC in La Union and moved to San Miguel. His next memories were of waking up at an Air Force hospital in Texas . Thanks to Morgan Gandy, the SF medic who saved Tim’s life that night, and Major General (ret) Kenneth Bowra, we have assembled and prepared an awards packet on Tim’s behalf. This to see him awarded the Purple Heart he is so long overdue, and the CIB and AFEM (El Salvador) he’d been recommended for in the Joint Staff/J3 staff paper for combat awards and decorations (El Salvador) submitted to GEN Bowra now years ago by Colonel John McMullen. Most of all Tim offers he no longer feels “swept under the rug and forgotten” – and he now has answers to the questions he’s had for years – DOL!

From Tim Hodge just moments ago –

Reading through this, memories and recollections, really brings home the gravity of the situation I was in. For several years I never knew anything about the chopper going down and the loss of lives that were on my behalf. When I was told about the chopper going down and everybody dying, I was told the reason for the delay in my knowledge was so that I would not take on the burden of knowledge that they sacrificed their lives for mine. I don’t know if it was a fair trade, but I have had 36 years now; 36 years and six days. I don’t know what to think.

Please pass my heartfelt gratitude on to everyone who has written narratives of memories and descriptions. People asked me if I ever went and saw any of my old friends from Group. I hope we said “No, they need to know that they are invincible. We all knew we could die. No one, absolutely no one told me I might live.”

With great respect,

Tim Hodge

SP4 Dawson, according to DOA MEMO for COL John P. McMullen, J-33. SOD dated 15 JUL 99 was awarded the POW medal posthumously along with LTC Pickett; “2. On 14 Jun 99, the Secretary of the Army approved the posthumous award of the POW Medal to LTC Pickett and PFC Dawson. This determination was based on their being shot down, captured and later killed by El Salvadoran Rebels (FMLN) on 2 Jan 91. As CWO Scott died from injuries he sustained in the helicopter crash, he is not eligible for the POW Medal.” signed by Bernard P. Gabriel, GS Chief, Military Awards Branch. I could provide a copy. I published much of this on http://www.USContraWar.com along with a memorial page for these three heroes. Pickett’s family shared other details and data with me directly. I hope this helps. In July, 2023, the VFW voted to adopt Resolution 419 – Honduras requesting that Congress issue the AFEM for service in Honduras. Pickett, Dawson, Scott and many others who perished in ES were all based in Honduras.

From Greg Walker:

“Initially it was believed SP4 Dawson (promoted to SP4 upon death) had been posthumously awarded the POW medal. That did not occur and Colonel Pickett’s posthumous POW medal was only authorized after a bitter fight between his father and the Army. I spoke with SP4 Dawson’s surviving sister when the Deputy Chief Sims’ HRC letter reached me and she confirmed her brother had yet to be so recognized. Had the Army authorized the award Mr. Sims would have shared that with both the SECDEF and myself. I continue to track the progress of both Dawson and SSG (ret) Tim Hodge’s pending award packets with HRC and the SECDEF.”

Author Greg Walker received this from Ian Rutherford:

Dear Greg, would like to share with you. May 13th, 1991, Cpt Sashai Dawn, 1lt Vicki Boyd, and Ssg Linda Simonds, all female medevac crew were killed in Honduras. They were from the 126th medical air ambulance, Sacramento CA National Guard. They were on a nighttime medevac operation to the TACAN radar site in northern Honduras. A soldier at the site had a ruptured hernia requiring medevac. The TACAN site was actively involved in monitoring/ tracking El Sal air traffic.

The female crew crashed into a cliff face near La Taz while enroute to the radar site. The crew chief, regular army William Jarrell somehow survived the crash. Historically speaking I believe they are Americas first female medevac crew to lose their lives while serving in conflict but they are not recognized due to no AFEM for Honduras and at the time of their death no El Sal AFEM either.

Cpt Dawn was very irrational, combative, and not normal the night of her death. Many years later, we learned of quinism caused by the malaria meds we were given… (see research at website of the quinism foundation quinism.org). It is not provable but I suspect quinism contributed to their deaths, she was displaying many of the symptoms. But back then we didn’t know anything about mefloquine problems.

Regardless, they were flying in an area of hostility where many insurgent groups were still active, and they also died while directly supporting an El Sal contributing facility, and have never received any recognition for it. Their crash also brought about a policy change, no more National Guard pilots would be flying in Honduras, a slap in the face to Guard pilots.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for your service and thank you for all that you have done for the veteran community. You have inspired me to try to contribute more. I greatly appreciate any sharing of this story you might be able to do, I hope they might receive proper honor and recognition someday. — Ian Rutherford.

If Pickett was awarded the POW award I think that should be awarded to Dawson AND Scott

My uncle was Lt.Colonel Joseph Lujan. I was a young child when he died, but the memories of my grandmother screaming when she was notified about his death will haunt me forever. It’s a scream you never want to hear. That of a mother, who has just lost her child. Thank you for keeping his story alive. My family has searched for answers for so long. To this day we can’t speak about it without shedding tears. My grandmother passed away in 2017. I know there was a part of her that was hoping one day she would get the truth. I still don’t think we have the complete story, but it’s starting to make a more sense when you piece all the stories together. Our family lost a great man July 15, 1987. #stopthecoverup