FALLEN SOLDIER

Colonel James “Nick” Rowe

Colonel James “Nick” Rowe

Part 2 — Death in Quezon City

Part I – Fallen Soldier

SERE flourishes and Nick Rowe is offered another opportunity to serve overseas. Despite the knowledge there was now a North Vietnamese bounty on his head in lieu of his successful escape from captivity, Rowe accepts assignment to JUSMAG in the Philippines. Fast approaching the point in his career where he could no longer expect to be a field commander, he tells former Green Beret and specialty knife designer, Al Mar, that the JUSMAG assignment could be his “last hurrah”, meaning once it was over he’d again be forced to become a “paper pusher”.

Part II – Death in Quezon City

By Greg Walker (ret), Special Forces

“Colonel Rowe being a key official in the JUSMAG is a direct participant in the U.S. designed ‘total war’ counterinsurgency program of the Aquino regime. JUSMAG is responsible for the overall planning, supervision and implementation of U.S. military assistance and training, as well as giving clear support to the AFP fascist military actions against the revolutionary forces and the Filipino masses.” — Rolly Kintanar, Chief of Staff, New People’s Army, 22 April 1989

“I’m either number 2 or number 3 on their list at JUSMAG and have taken the actions available to me to make it more difficult for them…Their targeting instructions are for an officer, involved In the counterinsurgency effort. DAO and JUSMAG are ground zero. It is many things here, but not dull.” — Colonel James “Nick” Rowe, Letter to CSM Dan Pitzer, 7 April 1989

The joint U.S./Filipino investigation into the assassination of Nick Rowe was in full swing when CSM (ret) Dan Pitzer, Rowe’s fellow POW in Vietnam for four long years and now the senior civilian SERE instructor at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, called me. Susan Rowe, Nick’s widow, wanted to do a public story about her husband and his murder just months earlier. She would meet with me but only with a public affairs officer from the Special Warfare Center initially present, Dan said. Ms. Rowe would not discuss specific details of the assassination due to the official probe taking place. However, I could access newspaper accounts, personal letters and interview friends of Colonel Rowe who had first-hand information they wanted to share.

I would be staying with CSM Pitzer and his wife, Gail, during my visit to Fort Bragg. Dan and I had become close friends over the years prior to Nick’s death and whenever I was in Fayetteville it was understood I had a room at their home. When Dan passed away after a long battle with cancer in March 1995, Gail informed me he had left his silver Special Forces ring to me. I have worn it ever since.

Understandably the Command at the Special Warfare Center was concerned about Susan Rowe, and in retrospect, Dan Pitzer going public. So much so the PAO assigned to monitor my visit called Dan at home the day after I arrived in Fayetteville. Dan reassured the nervous officer by offering, in part, he and I had known each other for years. “I’ll vouch for him,” Dan said, “Greg’s staying with me…as a matter of fact he’s sitting here in my living room right now.”

After he’d hung up Dan smiled. “They’re scared shitless,” he offered.

It was time to go to work.

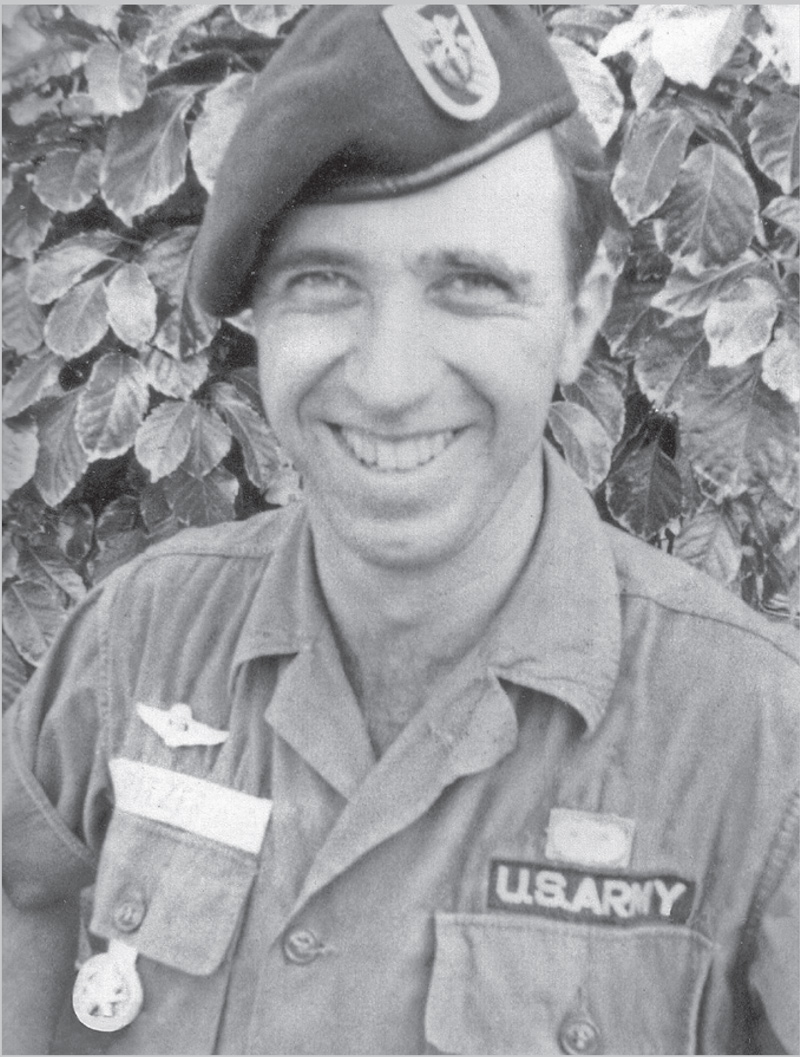

Command Sergeant Command Sergeant Major Daniel L. Pitzer was born Nov. 23, 1930 in Fairview, WV. He joined the West Virginia National Guard in December 1947, and attended and graduated from the West Virginian Public Schools in 1950. During his first year of college, his National Guard unit was called to active duty and moved to Fort Benning, Ga. Staff Sgt. Pitzer joined the active Army, volunteering for airborne training. He received his airborne wings on his 21st birthday. His first assignment was to the XVIII Airborne Corps Artillery as a communications team leader, and later transferred to the 5th RCT in Korea. Following the end of the Korean Conflict, he was transferred to Otsu, Japan, where he was assigned to Headquarters, South West Command, the Infantry School at Fort Benning, the 3rd Armored Division Combat Command “A’ in Kirchgoens, Germany, and finally to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, N.C.

He volunteered for Special Forces in 1960 and served as a medic, heavy and light weapons sergeant and team leader on various A-teams during his 15-year military career. He arrived in the Republic of Vietnam in July of 1963. Four months later, while out on patrol with the Vietnamese Special Forces (LLDB), he was wounded and captured by the Viet Cong. He was held as a prisoner of war for four years, gaining release in 1967. One of his fellow POWs was Nick Rowe. On Nov. 11, 1967, after four years of torture and suffering from beri beri, malnutrition, malaria, hepatitis and having lost more than 85 lbs, he was returned to U.S. control.

Upon his return to the United States, he was hospitalized for eight months at Fort Bragg’s Womack Army Hospital, and following his release he served in both the 6th Special Forces Group (A) and the 5th Special Forces Group(A). His follow-on assignment was as an instructor with the U.S. Army JFK Center for Military Assistance. He was promoted to sergeant major on April 20, 1972. During this period from 1969 to 1973, he traveled extensively for the Department of Defense speaking to various community groups about the plight of the American POW. He also assisted in the Operation Homecoming for the released POWs in 1973.

Medically retired in 1975, he continued working in the arena of POW affairs, focusing on getting an accounting of those still listed as missing in action. During this period, he assisted the U.S. Navy in the establishment and operation of their Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) Training Program in San Diego. From 1987 until his death in 1995, he served as an instructor with the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School’s SERE course.

His decorations include: the Silver Star Medal, Bronze Star Medal, Legion of Merit, two Purple Heart Medals, Meritorious Service Medal, Air Medal, Prisoner of War Medal, Good Conduct Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Korean Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal w/60 devices, United Nations Service Medal, Overseas Ribbon, Meritorious Unit Commendation, Master Parachutist Badge and Combat Infantry Badge.” – Distinguished Member of the Special Forces Regiment, https://www.soc.mil/SWCS/RegimentalHonors/_pdf/sf_pitzer.pdf

The Joint Military Assistance Group

The Joint Military Assistance Group (JUSMAG) was created in March 1947 under the Republic of the Philippines / United States Military Assistance Pact. It was composed of active-duty military personnel who advise the armed forces of the Philippines (AFP) on military and naval matters. Ground Forces director (GFD) is not a Special Forces assignment, although Rowe had converted his branch specialty from military intelligence to special operations once SO became a career field for officers. Since Rowe possessed a long association with Special Forces and indeed wore the 18-series Crossed Arrows insignia, he could not help but to have been perceived as a “Green Beret” officer once on the ground in Manila.

Colonel Rowe was responsible for overseeing the material needs of the AFP when it came to military procurement. It was a delicate job. Rowe once remarked to a former JUSMAG commander, with whom he’d discussed his upcoming assignment, that he was “not going to be Santa Claus” when it came to carrying out his duties. He would, upon arriving in the Philippines, ensure the AFP received the materials, arms, and munitions they needed from the United States to successfully confront the ongoing insurgency. That meant working closely with Filipino commanders at the highest level of the AFP as well as interfacing with the Aquino government.

At the same time the colonel was considered a source of information and advice when it came to the Filipino counterinsurgency effort.

And there was good reason for this assessment. According to Fred Fuller, who was working at the Special Warfare Center’s library when Rowe accepted the JUSMAG assignment, the colonel tagged him as a subject matter expert on the Philippines and the then ongoing communist-backed insurgency. Fuller, a longtime and very affable librarian, was honored to help. “He [Rowe] was full of questions for me,” recounted Fuller when we met at Bragg. He wanted to know everything. We spent hours together. He was detailed in his curiosity.” Fuller also shared Rowe’s understanding that the [North] Vietnamese had not forgotten about his years of captivity at their hands and his successful escape. “Nick had been offered several assignments after his standing up the SERE program. He was said to be on track to make his first star and he needed an impressive overseas tour. He’d been warned by friends that the Vietnamese still had a bounty on his head and by going to the Philippines he’d been well within arms’ reach of anyone in Vietnam who wanted him dead. At the same time he wanted another shot at the communists and felt he could make a difference by taking the JUSMAG assignment.”

On April 23, 1989, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported that “…his [Rowe’s] skill as a counterinsurgency expert no doubt was the primary reason for his assignment here.” AFP spokesperson Colonel Benjamin Enrile stated, “Rowe was an adviser or consultant on military matters.” In his eulogy, one of Nick’s closest friends, Major Robert Adolph, recalled that not only the JUSMAG officer’s knowledge caused Rowe to be targeted for assassination but that Rowe “…constantly exposed himself to greater danger by working closely with American and Filipino soldiers in the field.” Major Adolph believed it to be very possible Nick Rowe may have been killed because “…of the success of his programs against the insurgents.”

One of Rowe’s programs included the highly successful special operations teams (SOTs) made up of exceptionally trained Filipino Marines who were trained and then charged with taking the Aquino government’s counterpropaganda message to those remote areas infiltrated by the communist New People’s Army (NPA). The program included village screenings of the movie “The Killing Fields” dubbed in Tagalog, “…has proven to be immensely successful. For their part the NPA has responded with stealthy teach-ins of their own – and violence,” claimed an article in Asia Week magazine. “A councilman in Calmachin village was recently murdered for his pro-government stance.”

According to Dan Pitzer, his fellow former POW’s counterinsurgency work was non-violent in nature. “As an author and writer Nick understood better than most the power of the pen. He’d learned how important psychological operations were while in the hands of the Viet Cong, and he was sharing those lessons with the AFP.” Further confirmation of this sophisticated approach by Rowe is evidenced in a personal letter dated May 14, 1989, to Susan Rowe from the Commander of the 13th Air Force Medical Center in which the officer wrote, “For my part I am determined to continue the medical and civic action initiatives started by Nick.”

At the same time, though, Colonel Rowe was likewise keeping his commitment to hold the AFP accountable for the military aid the United States was providing the Aquino government under President Cory Aquino. To include investigating the illegal distribution of arms and munitions to Filipino para-military actors opposed to the Aquino government. The weapons were suspected of being siphoned off by anti-Aquino military commanders to be used in a future coup attempt. At JUSMAG, Rowe had finished an official report detailing his concerns to include naming names.

In short, Nick Rowe had become a viable target for the communist insurgents suffering from his hands-on involvement to counter them, and by anti-Aquino hardliners within the government and military who were seeking a return to a Marcos authoritarian (and very corrupt) dynasty in Manila.

Al Mar's SERE (Survive-Escape-Resist-Evade) knife was the first knife accepted for use by Special Forces Colonel Nick Rowe for the SERE Instructor School at Camp McCall North Carolina.

Author Greg Walker, at left, holds Set #2 of the limited edition set from Al Mar, designed in honor of his friend, Nick Rowe. Right Greg's son, Dr. Brandon Walker, former U.S. Marine and SERE graduate, now also the owner of the CSM Pitzer's Rowe Commemorative Set.

If they want to get you, they will

Contrary to some reports, Colonel Rowe knew of his selection as a target for the NPA and their urban assassins, called “sparrows”. In one of his last letters, he illustrates his precautions against a successful attempt on his life. “I’ve got a hardened vehicle,” he wrote, “and a trained driver for my official travel in the Manila-Clark AFB-Subic area; an AFP guard in the house 24 hours a day; and a stand-by security team should a hit go down at home or in the immediate area.” According to Rowe himself, the Alex Boncayo Brigade (an NPA urban unit operating in Manila, “…has done some very effective work in the past and continues to take out military and police almost at will.” Brig. General Alexander Aguirre (Commander, Task Force Rowe), would later confirm Rowe had indeed been “…killed by sparrows, or armed urban partisans of the NPA.” Defense News would report the arrest of Donato Continente, who alleges being “…a member of the five-man team of communist rebels assigned to kill Rowe.”

On the morning of April 21, 1989, Colonel Rowe and his Filipino driver, Joaquin Vinuya, left Rowe’s home for the JUSMAG compound located in Quezon City. Even though it was Friday he had a heavy schedule, to include an equipment demonstration for the AFP later in the evening. Per Filipino law neither man was armed, although Rowe did have access to weaponry both at his home and in his office. Up until several days prior to his murder there had been a chase car that shadowed the colonel as he traveled between his residence and the Quezon compound. According to sources requesting anonymity, this as well as other chase vehicles assigned to priority personnel believed to be targeted by the NPA, had been recently pulled off. “It was simply a case of misjudgment,” allowed one source.

AFP spokesmen reported the NPA sparrow team followed Rowe’s silver-grey sedan from his home into the city. As was his habit, Colonel Rowe was sitting directly behind his driver and carrying a specially armored briefcase which he used as a secondary shield while traveling around Manila. The automobile itself had been hardened by Rowe. According to Dan Pitzer, often in contact with Rowe, “Nick told me after they’d installed the glass in is car, he’d personally fired a .44 Magnum at the windows with no effect. He believed the interior of the vehicle was as bullet-proof as could be expected.”

At 0715, just two blocks from the JUSMAG compound, the sparrows initiated their attack by driving a stolen vehicle up alongside Rowe’s Mitsubishi Galant, opening fire with at least one and possibly two M16 automatic rifles, as well as a .45 caliber pistol. The gunmen concentrated on the car’s window, firing short bursts of between five to six rounds, attempting to “drill” through the hardened glass. A total of 21 rounds struck the window and car as Rowe’s driver attempted to outmaneuver his assailants.

Vinuya was wounded by flying glass as the interior portion of the windows began to fragment under the concentrated high-velocity impact of the 5.56 rounds. As surmised by Rowe, the hardened vehicle withstood the small arms assault. Only a single bullet found its way into the passenger compartment. This round penetrating a structural portion of the door-frame that could not be armored. It was this bullet that struck Nick Rowe in the back of his neck as he was throwing himself down across the rear seat, killing him instantly.

“You could have fired 1000 rounds at that car, and maybe have gotten one bullet to enter where the one that killed Nick did,” observed one combat veteran who was near the scene. “If the Colonel had continued sitting upright, the bullet would have missed him, had he gotten down on the rear seat a second sooner, the bullet would have missed him. Call it Fate or whatever, they got lucky that morning.”

To his great credit, Vinuya carried out his duties as Rowe’s driver, despite his painful wounds. He piloted the car into the JUSMAG compound where it was quickly secured. Rowe was immediately transported to the AFP Medical Center where he was pronounced dead at 0840.

Colonel Rowe is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His grave is on the hill next to the monument of the Unknown Soldier. Inscribed on his gravestone are the words from a poem he wrote in 1964 while a POW:

So look up ahead at times to come,

despair is not for us.

We have a world and more to see,

while this remains behind.

In one of his final letters Nick Rowe said of his experience in the Philippines: “It’s interesting to watch history being written around me…so long as the Jolly Green makes it to the extraction LZ and we make the pick-up window.” On April 21 an H-53 Jolly Green, known for its role in Vietnam as a flying rescue platform, was dispatched from Clark Air Force Base to recover the body of Colonel James “Nick” Rowe. For a second time a helicopter was lifting him free from his Forest of Darkness, beginning the long journey home to the country he loved.

From Five Years to Freedom

by Colonel Nick Rowe, American Soldier

“I have entered and I have returned. If enter you must and enter you will, then remember these thoughts:

“Know who you are and from whence you came; Remember the light and the sun’s cleansing warmth; Mark well the spot at which you entered and mark each spot at which you stop;

Remember your Faith and keep it strong; Do not expect to find a path and be prepared to make your own;

When it is day you must travel far, but when it is dark, then rest and remember;

Conquer the urge to panic and run, for they will insure you’ll never return.

When daylight comes, then rest not long and quickly seek Your way or you, like the leaves will also decay. For night falls early in the forest and darkness blinds you, hides the way.”

Aftermath

Certainly, Nick Rowe knew the potential danger of his assignment. Some have tried to label Rowe as clairvoyant about his assassination, forgetting he was a highly capable Intelligence officer. If anyone could read the signals his presence would send the NPA, it was Nick Rowe. “If Nick wasn’t anything else he was tenacious,” remembered Dan Pitzer. “It was both his strongest and weakest trait. Even in the camps he wouldn’t back off.”

And what of Rolly Kintanar, Chief of Staff for the New People’s Army and the man who announced the NPA’s role in killing Rowe?

“The communist New People’s Army (NPA) has admitted to last week’s killing of its former chief Romulo Kintanar, saying it was done as “punishment” for numerous crimes committed against the revolutionary movement and the people, a rebel spokesperson yesterday…Kintanar was gunned down in cold blood while having lunch with his bodyguards at a Japanese restaurant in Manila’s northern suburb of Quezon City on Thursday… On Saturday, President Gloria Arroyo ordered no let up in the campaign against criminals and terrorist insurgents who will be given no quarter in this fight.” — January 27, 2003, https://gulfnews.com/uae/npa-admits-killing-kintanar-1.345989

Romulo "Rolly" Kintanar

REMEMBERING CSM DAN PITZER

Greg Walker retired from the United States Army/Special Forces in 2005. In 1980, while at the Defense Language School in Monterey, California, he was offered a senior SERE instructor position by Colonel Rowe. However, the Army’s priority to staff the 3/7th Special Forces Group then in Panama overrode even Colonel Rowe’s request as he sought to staff the new program at Fort Bragg. Some years later Mr. Walker, along with Ms. Gail Pitzer, and at the request of MG Kenneth Bowra (ret), created the CSM Dan Pitzer Conference Room at USASFC. “When I asked Dan why he’d never written a book about his own experiences as a POW alongside Nick, Dan simply smiled at me and said “Nick’s book was my book, too.”

Greg Walker and his service pup, Tommy

With all the SF guys in the Subic Bay Area, that lived there, I can not understand why they did not secretly hunt down and kill those who killed this Best of the Best SF soldiers. I remember being in the bar in CCS and seeing Nick Rowe the day he escaped on a film appealing to the Viet Cong he had known over those years. To prioritize his writing this appeal and refusing medical care until he did that, spoke al,l of this HERO. An amazing person who never received the recognition he so deserved. Of course he didn’t care about hisSELF, only the rest of us.

Exactly. They could and should have secretly hunt down the pepertrators.

Today is the day we lost you Col. Rowe, it is hard to believe 34 years have past. I am so grateful for everything you and CSM Pitzer taught and shared with us. I was able to meet Mr. Camacho and Sue again several years ago at a special P.O.W. exhibit at the U.S. Airborne and Spec Ops Museum. Needless to say, je n’oublierai jamais.

I was in B Troop, 7th Squadron, 1st Air Cavalry at Vinh Long Airfield, when Nick was rescued from the U Minh Forest. I saw him pass through our company area and heard what all the excitement was about. I have his book and a Manila newspaper clipping that my Mother-In-Law, who resides in Cainta, Rizal, sent me.

In later actions in the U Minh, we lost a considerable number helicopters in one day in February 1969. Col. Hackworth describes some of that action in one of his books.

Thank you for honoring a man who should have his story told in all American schools. His ability to serve something greater than self, think unconventionally and conviction to being a present leader sets an example matched by few in history.