From Thailand to Cambodia — 1996

Cambodia — Angkor Wat, Siem Reap (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

By Marc Yablonka

After three weeks of being Tom Yum souped all over Thailand courtesy of the Thai Ministry of Tourism in 1996, in a weird way, flying into still war-torn Cambodia was a bit of a relief. Not that Thailand didn’t mean anything.

While there, I filed a piece for American Veteran magazine on the Kwae River Bridge made famous by the 1957 film Bridge over the River Kwai, winner of six Academy Awards. I tried to walk across a rebuilt version of that bridge in a Southeast Asian downpour and gave up half way across for fear of slipping off and falling to my demise.

I wrote about the nearby Kanchanaburi War Museum, housed in a longhouse, with its war relics and photos all laid out on tables informing visitors of the Siamese complicity with the invading Japanese. Meanwhile, a rusted from rain locomotive used by the Japanese to pull trainloads of Japanese soldiers who tortured Allied POWs, forcing them to build the Burma (“Death”) Railway, sat astride the museum.

Next, my fellow journalists and I were guided to the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery where 6,858 mainly Australian and Dutch POWs, who could not withstand the torture of their Japanese captors, are buried.

I became close to two of those journalists: Rolla J. “Bud” Crick, who was on assignment for the Oregonian, newspaper of his hometown, Portland. But Bud had made his mark in journalism years before as a US Army reporter/photographer during World War II for Pacific Stars and Stripes, which sent him to such hazardous duty stations as the Philippines.

They also sent him to Japan a mere few days after the atomic bombs were dropped to photograph Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It’s a wonder that neither Bud nor his offspring did not come down with the infamous, disfiguring, often deadly Hibakusha disease suffered by multitudes of Japanese citizens after the war. Bud lived way into his 90s.

Another journalist along for the ride was Sherry Spitsnaugle. Sherry was on assignment for her hometown paper, the Denver Post. She still writes excellent travel pieces for a variety of online sites.

There was also my friend Jim Caccavo. Jim was the Red Cross photographer/writer in Vietnam between 1968 and `70, during which he also freelanced for Newsweek magazine.

Cambodian soldier guarding the US Embassy, Phnom Penh (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

It’s thanks to Jim that I had my one and only experience, thank you very much, at Pussy Galore’s in Padpong, Bangkok. Until then, I never knew totally nude bar girls could dance the night away doing such unbelievable things with their anatomy!

Bud, Sherry, and I said goodbye to Jim at the Airport Hotel at Don Muang International Airport at the end of our Thailand journey. He was off to Hanoi and the three of us were Phnom Penh bound.

While Sherry stayed with friends, Bud and I holed up at the Cambodiana Hotel, purportedly the safest hotel in what was still cowboy town. And still, the hotel wasn’t safe enough to not have guards on each floor armed with M-16s. You didn’t go out at night on foot, and you made damn sure that the hotel car took you where you were going and picked you up when you wanted to come back.

Unlike Vietnam, where the cyclo drivers adopt you for an honest pay off at the end of your journey, the cyclo drivers in PP were known to ride you down some dark alley, stop, beat the crap out of you, and steal your money.

I interviewed hotel manager Helen Lim for a piece I wrote on Cambodia for the Straits Times of Singapore. “You journalists always insist on going into dangerous places where you shouldn’t go, and God bless you if you do,” she told me in the course of our interview.

Speaking of going into dangerous places, I said hello to then CNN field reporter Peter Arnett in the elevator of the Cambodiana one night. I also got called a traitor by a spook in the hotel bar when I told him I’d done two tours with the Israeli Defense Forces. Damn! One less friend in the world!

Australian UNTAC Troops, Foreign Correspondents Club, Phnom Penh (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

One of the places that was not dangerous was the Foreign Correspondents Club, which overlooked the muddy Mekong River. In addition to local and foreign journalists, it was also the watering hole for UNTAC (United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia) troops, embassy types, and backpackers alike.

And being that the windows were glassless, hundreds of geckos, the lizards American GIs in Vietnam dubbed “Fuck you lizards” for the noises they made at night, frequented the place.

The FCC was the first place I ran into renowned British Vietnam War photojournalist, Tim Page. I would meet Page again in Washington, D.C. a year later, when I made my first pilgrimage to the Vietnam Memorial along with him and our mutual friend Sergio Ortiz, USMC combat correspondent based at the Da Nang Press Center during the war.

The FCC was where Bud and I lunched with Sherry’s friend, the economic attaché at the American Embassy, who told us, “There are still Khmer Rouge in Phnom Penh. They’ve just traded in their AK-47s and gone into business.”

Whether or not they had traded in their AKs in recent years did not take away from the horrific photographs of the past I witnessed at Toul Sleng in Phnom Penh. Toul Sleng had been a school which was converted into a sort of clearing house where it was decided which citizen would go where after being tortured…if he or she lived.

Victims of Pol Pot’s genocide were killed just for wearing glasses, just for speaking French, just for being teachers, just for…on and on and on. Three million of them. Very Nazi like, everyone who passed through Toul Sleng on their way to an uncertain future had his or her photo taken. That’s how well the bastards documented their own horror.

Legend holds that the Khmer Rouge photographer took his last photo there when he looked through his camera viewfinder and saw the face of his own uncle staring back at him.

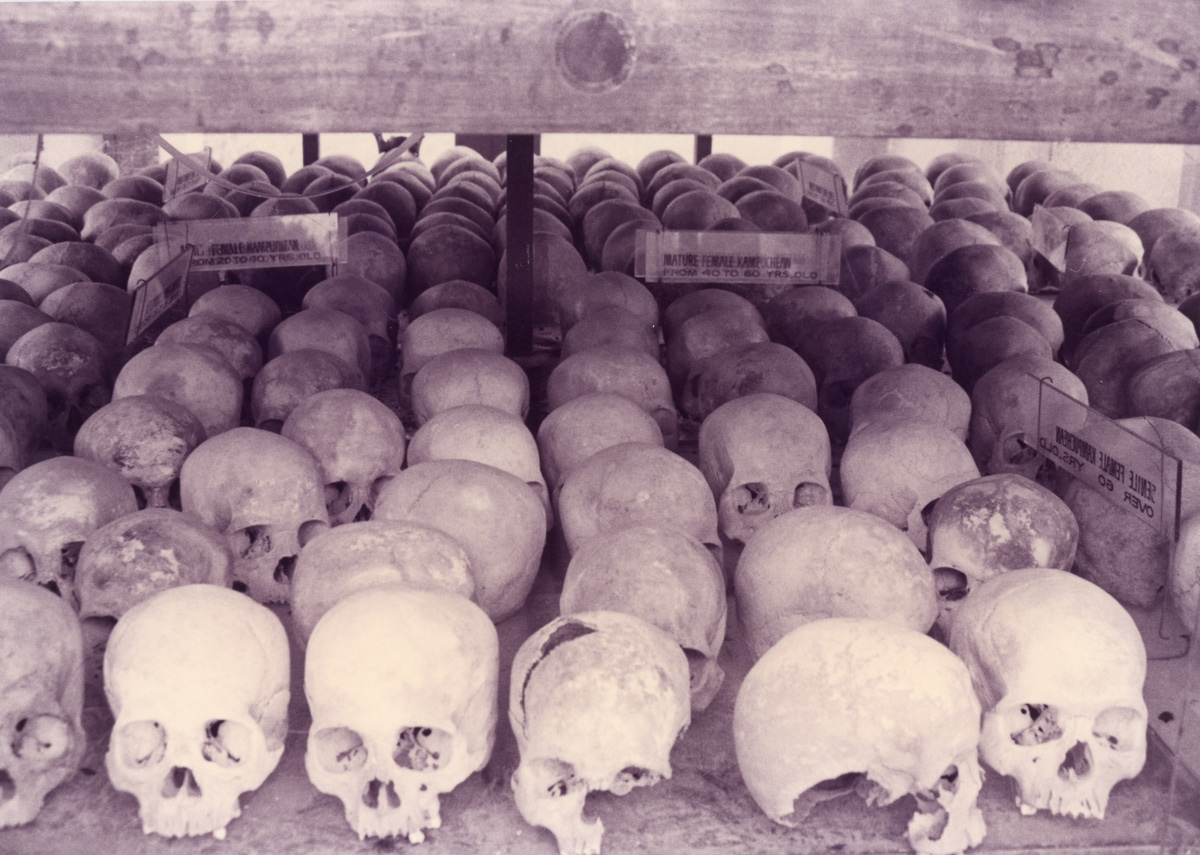

One does not have to venture into the Killing Fields that Helen Lim warned against to see further evidence of Khmer Rouge horrors. Fourteen kms. outside of Phnom Penh lies Choeung Ek, an open field in the middle of nowhere which includes a Buddhist stupa with shelf after shelf after shelf with nothing but skulls.

As I walked through Choeung Ek with a guide, he pointed to the ground. “Look,” he said. My tired eyes didn’t make it out at first, but when they focused, I could see human teeth and bones staring up at me from their place half buried in the dirt at my feet.

Having never journeyed to Auschwitz, where my grandfather met his fate, that was the first time Man’s inhumanity to Man slapped me across the face.

Buddhist stupa at Choeung Ek, Phnom Penh (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

At Sihanouk’s Palace, I did enjoy one comic respite from the tragedies. There, I was lectured on the virtues of Buddhism by a monk. As I looked across the grounds, I spotted one of his fellow monks smoking a cigarette. “What about him?” I asked my monk friend. “Oh him?” my friend replied. “He’s just a weekend monk!”

Bud, Sherry, and I next flew a Royal Air Cambodge ATR-72 prop jet and made pilgrimage to Siem Reap’s wondrous Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom complexes, dating back to the confluence of Hinduism and Buddhism that is part of Cambodia’s ancient history. But for French explorer Henri Mouhout around 1860, the wonder that is both would still be covered over by Southeast Asian jungle.

We were followed by street urchins selling baskets and kramas, the national neckwear of all Cambodians (I bought a black and white one so as not to be taken for a sympathizer of the Khmer Rouge, who wore red ones).

Even with that, the peace that my journo friends and I found there that weekend I shall never forget. At the same time, I will also never forget the Khmer Rouge bullet holes that dotted the walls of both complexes.

From Angkor Wat, we made our way to Wat Tmeay, a hooch-laden village where the wives of all the men killed there during Pol Pot’s reign pledged their lives to Buddha and, as Buddhist nuns, shaved their heads.

Meanwhile, nearby, their husbands’ skulls lay piled atop one another in yet another stupa with an open door so villagers and tourists alike could pay them homage.

Something so moved me to be among the dear nuns, that I reached into my billfold, took out US$10, and handed it to one of them.

All of a sudden, the entire group of them raised their hands in the Buddhist “Wai” (their hands pressed together in a praying motion so often seen in Southeast Asia), and they began to sing a mantra.

Buddhist nuns, Wat Tmeay, singing the author a mantra. (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

“Do you realize what you have done?” our guide questioned me in broken English. For a split second I was afraid I was going to receive a personal escort out of Cambodia for some terrible economic misdeed. “What?” I squirmed. “You’ve given them enough money for rice for a month!”

As I wrote in my Straits Times piece, “It was hard to focus a Nikon through tears,” but I did just that and came home with a picture of those nuns singing that mantra to yours truly as a thank you.

Bud, Sherry, and I flew back to Phnom Penh and went our separate ways. Before I left the city, I stopped by the “Russian” Market and bought an ivory Buddha which still hangs around my neck next to my Star of David. Twenty-seven years later, Cambodia remains indelible in my mind.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, and Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

It was an eye opener. We were some of the 1st teams in their after the democratic elections in 93. Some teams stayed in the Combodiana river boat then on to the Regent park hotel. There was only one working stop light in town. Spent a lot of evenings at the Heart of Darkness club. Some teams were doing de-mining along with Medcap and Encaps. Spent time also at the FCCC. Im sure its different by now and cleaned up. It was still the wild west in 93-96. Most teams came out of Oki. Good story

MLG

Thank you very much for your kind words, Mel!

V/r,

Marc