“Get Ready!”

By Jim Morris

Originally published in the January 2020 Sentinel

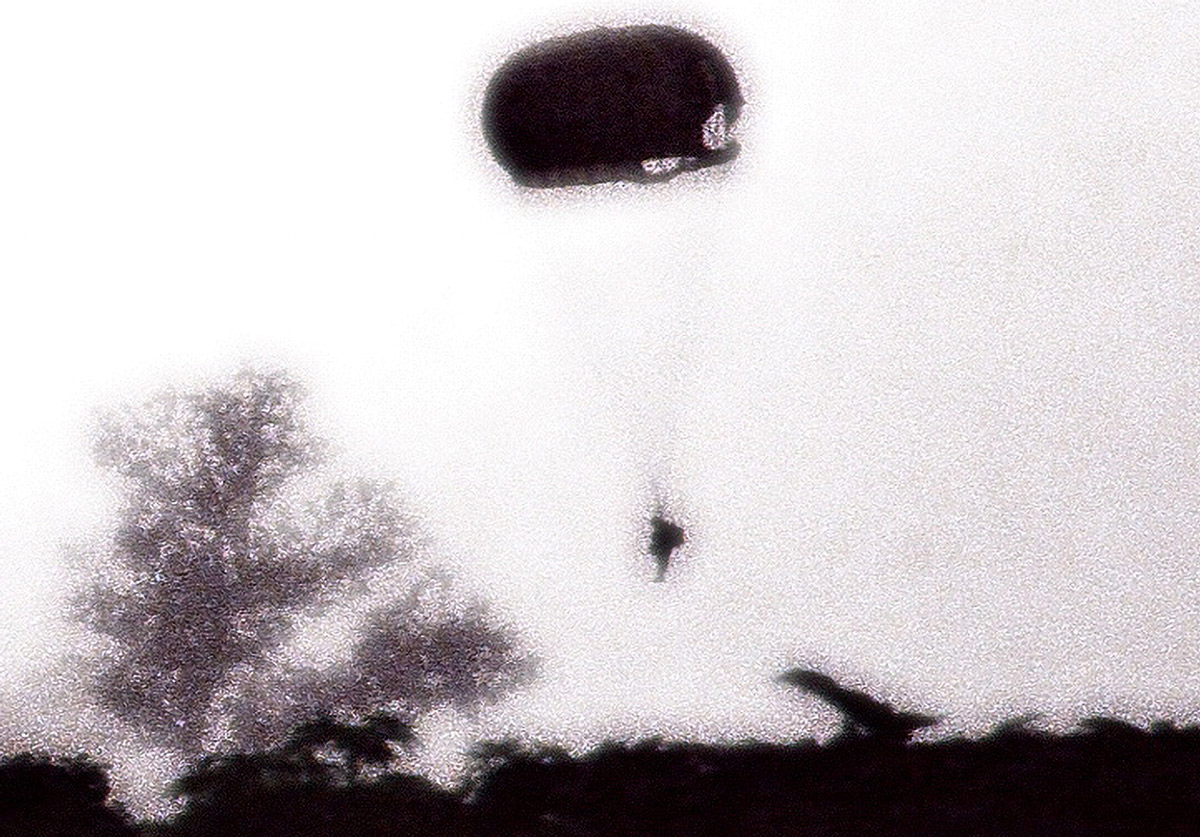

The Jumpmaster stood in front of the tailgate wearing all his gear, boots, fatigues, helmet, T10 parachute in back and reserve in front. His rucksack was slung on a drop line under the reserve and an M16 was slung under the strap of the waistband. His hand was out in the Get Ready hand and arm signal, like a crossing guard signaling stop. Rawlins stirred on the red nylon seat and looked at Burks across the aisle. Burks looked scared. Rawlins wasn’t scared, exactly, but he had a few butterflies in his gut and he needed to get them in formation. A jump was serious business, and a night combat equipment jump was serious business indeed. Every man on the plane carried about 90 pounds, including the two chutes and all his combat gear.

He’d been in the midst of a funny dream when the Jumpmaster yelled “Get Ready!” and held out his hand. He’d been old, in a hospital bed, more fucking tubes coming out of him than under a meatball on a plate of spaghetti. His whole family was softshoeing around in the room. He was dying and knew it. He was full of morphine, so the pain wasn’t so bad. But it was just a dream.

He was nineteen and weighed 150 pounds, and he was about to make a night combat equipment jump on Yomitan Drop Zone on Okinawa. Both jump doors were open. It was cold and the wind roared like a tornado. You could smell the adrenalin. It sizzled, that adrenalin.

“Stand Up!” The Jumpmaster turned his hand over and lifted it from waist high. Rawlins reached across the aisle and took Burks hand and they pulled each other to their feet. All the weight of his gear now hung off him. The minute he left the airplane that weight would disappear, and when he hit the ground he would lose sixty pounds of it. Goddamn how he wanted out of that airplane.

The doctor came in the room. It smelled of hospital, of antiseptic and God knows what all else, that hospital smell. Rawlins hated that smell. His daughter, Julia, looked down at him. She was about fifty now. Her mother was dead. His grandsons sat in chairs across the room. Rawlins breathed and it made a wheezing, choky sound. “Are you comfortable, Dad?” Julia said.

“I’m dyin’,” he said. “How the fuck comfortable is that?”

“Dad,” she said, and then she stopped. Rawlins didn’t care. She’d always been bossy. She was the oldest of his kids, and she had bossed the others mercilessly, for all the good it did her, or them.

“How about a cigarette?”

“Dad,” she said, “you know you can’t have a cigarette.”

“Yeah,” he said. “It might cut my life expectancy from thirty minutes to twenty-nine.”

He shifted again. “Hook Up!” Everybody in the cargo compartment except the Air Force loadmaster, who wore a backpack with a D-ring instead of a static line, reached up and hooked their static line to the anchor line cable.

“Check Static Lines!” Rawlins tugged his static line to see it wouldn’t hop off the cable. Considering it had a sliding safety with a push-button release, that wasn’t very likely. The roar of the engines and the roar of the wind made it impossible to hear the Jumpmaster’s commands. Rawlins was roaring inside. His stomach did flip-flops. In a minute he was going to jump into the night one thousand feet above the shittiest drop zone in the Airborne, Yomitan, an old Japanese airstrip, crisscrossed with runways, plowed for vegetable gardening with concrete honey buckets full of human shit that the Okinawan farmers used to fertilize their fields, and bounded on one side by the East China Sea, two sides by rock quarries, and the other side by an Army Security Agency antenna farm. It was a nine-second DZ

That’s how long they had to clear sixty guys out of the airplane and then they’d be in the air a minute before they landed, on the DZ, on the airstrip, in one of the fucking honey buckets, or like the XO, in a high wind, with his canopy caught in telephone lines, wind slamming him repeatedly against the side of a house.

That’s if the chute opened. If it didn’t you had nine seconds to fix whatever was wrong or you were dead. And for that danger you got an extra fifty-five dollars a month.

“Check Equipment!” Rawlins checked his own reserve, and the backpack of the man ahead of him. Nothing was wrong. There was very little that could be wrong, at least that you could see in the dim light of an airplane at night, with the lights all red, so as not to screw up your night vision.

“Are you comfortable, Mr. Rawlins?” asked the doctor. How old was this kid, twenty? He didn’t look old enough to be a doctor. He didn’t look old enough to be an army medic. “I’d be comfortable if I had a fuckin’ cigarette,” he said.

“’Fraid not, Mr. Rawlins. With all this oxygen equipment this place would go up like a Bruce Willis movie.”

“Well, at least you got a decent reason. My daughter says it’s bad for my health.” He started to laugh but it turned into a wracking wheeze and coughing fit. He raised his hand, as though it had a cigarette in it, reflexively trying to take a drag. The hand was old. It looked like a skeleton hand covered with something like a pepperoni pizza. It was about the worst looking hand he had ever seen.

“Sound Off For Equipment Check!” What the hell was his number in the stick. Six, he was six. The count came from the back of the aircraft. “Fifteen okay!” There were four sticks of jumpers, two outboard and two inboard. Rawlins was number six in the right outboard stick. “Seven okay!” the guy behind him yelled and slapped Rawlins on the ass. He barely heard it over the engines and the wind. “Six okay!” Rawlins yelled and slapped the guy ahead of him on the ass.

The doctor was talking to Julia. “I’m afraid it won’t be long now, Mrs. Janizewski. Your father’s lungs are gone; his heart is gone. He’s seventy-five and he’s had a hard life. I don’t know why he’s alive now.”

Julia gave a weak grin. “He’s tough,” she said. “He was a paratrooper.”

The doctor said nothing. He didn’t know the difference between a paratrooper and a dung beetle. Rawlins wheezed. It sounded like broken equipment. He didn’t know how he was alive either, or why. He shoulda been dead how many times? Five that he could count, but here he was, expiring in this crappy-ass hospital

“Stand In the Door!” The first man moved into the door. The whole stick moved forward a step, outside foot forward, all in a line. When the first man disappeared they’d start a shuffle forward that gathered speed like a freight train, all in step, all synchronized, like they’d practiced so many times, to get clear of the airplane and land close together, ready to fight.

So much could go wrong. Rawlins remembered the time Burks had gone out, to the end of his static line, and just stopped. He hung flapping behind the aircraft. Everybody else, including Rawlins, jumped, and it’s a wonder nobody hit him. The approved thing to do in a case like that was to put your hand on your helmet to show you were conscious. Then they’d cut your static line and you’d pull your reserve. If you were unconscious they’d fly around as long as they could and then foam the runway, which in theory you might survive, but more likely you’d be sanded to death in suds.

But Burks didn’t do either of those things. He climbed hand over hand back into the aircraft. The loadmaster almost fainted when a hand came around the door from outside. That was some muscular Afro-American citizen.

The two boys got up and stood over Rawlins. Julie and the boys were looking down at him, two druggies and a real estate agent. He’d have been better off face down in a rice paddy. That would … ah, fuck it, what’s the diff? He’d had a life. He’d lived life like his ass was on fire. There was only one thing left to do. That was all the business he had left.

The light winked green, in the dark and the roaring aircraft. “Go!” the Jumpmaster shouted.

One guy disappeared from each door and the stick started stomping forward, weighted down with all that gear. He felt weak. He felt like he couldn’t breathe. He didn’t know how he could even stand up weighted down with all that shit. He shuffled forward. The guy ahead of him disappeared. Rawlins wheeled into the door and looked at the night. It was like he’d never seen it before. It was cold and blackness and that was all. He crouched, and grabbed the outside of the aircraft with both hands. He jumped up and out, into the night and the stars.

Every other jump he’d counted to four and felt the tug as the chute opened and deployed. But this time he just kept going.

About the Author:

Jim Morris joined 1st SFGA in 1962 for a 30-month tour, which included two TDY trips to Vietnam. After a two year break, he went back on active duty for a PCS tour with 5th SFG (A), six months as the B Co S-5, and then was conscripted to serve as the Group’s Public Information Officer (PIO). While with B-52 Project Delta on an operation in the Ashau Valley, he suffered a serious wound while trying to pull a Delta trooper to safety, which resulted in being medically retired.

As a civilian war correspondent he covered various wars in Latin America, the Mideast, and again in Southeast Asia, eventually settling down to writing and editing, primarily but not exclusively about military affairs.

He is the author of many books, including the classic memoir War Story, available in Ebook format in The Guerrilla Trilogy, which also includes his books Fighting Men and The Devil’s Secret Name . The Dreaming Circus was released in the summer of 2022 — information available at https://www.innertraditions.com/books/the-dreaming-circus.

Jim was editor of the Sentinel for 2020 and had just taken on editorship when this story was published in the January issue.

Yomitan dz was a short miserable rock (coral) strune old air field. I had the honor of making my jumpschool 5 on this damn mess. I was with the 400th USASA SOD (Abn) attached to the 1st SFA IN THE EARLY 60’S.