Hickory Hill

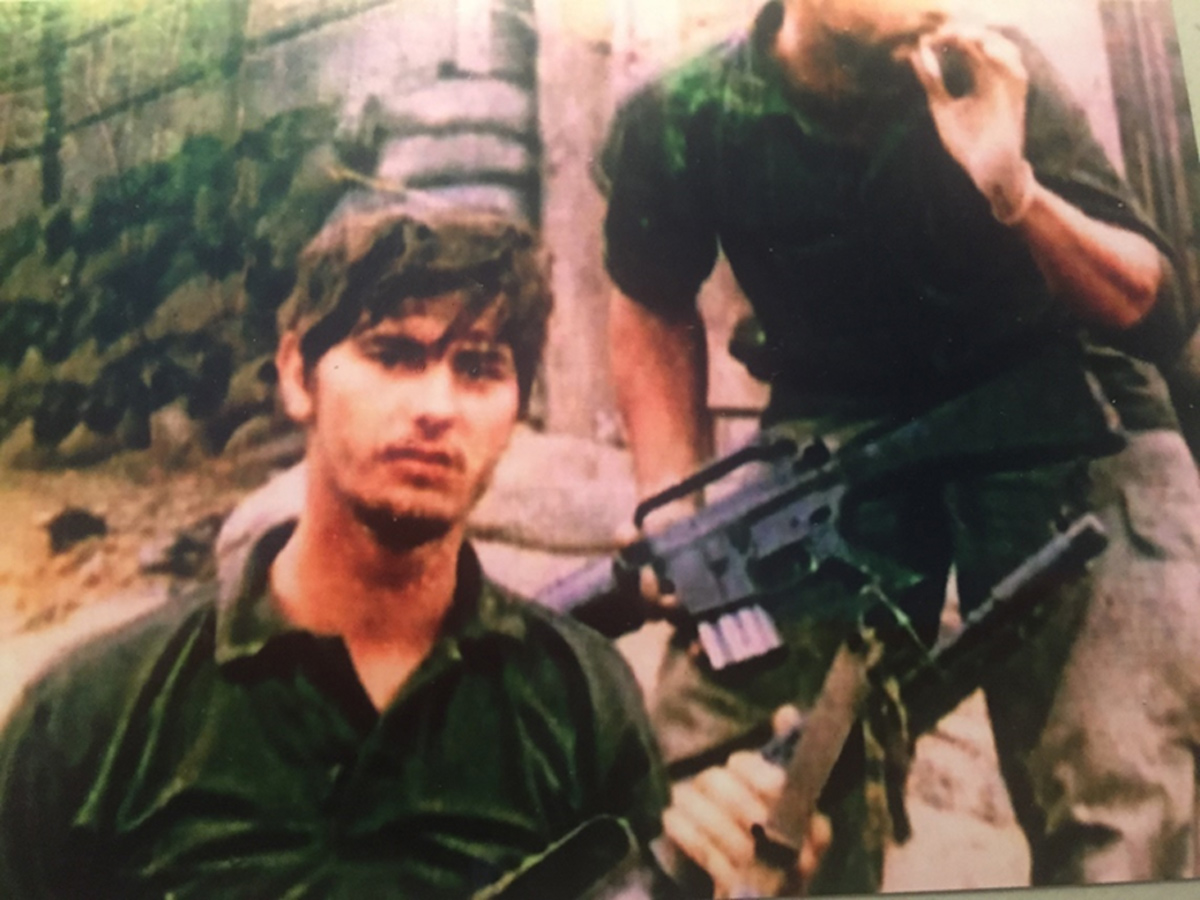

Jon Cavaiani in Vietnam with his CAR-15

By John Siegfried and Dr. Michael B. Evers

from Jon Robert Cavaiani: A Wolf Remembered, Chapter Four, reprinted with permission

“It doesn’t take a hero to order men to go into battle. It takes a hero to be one of those men who goes into battle.”

General H. Norman Schwarzkopf

Soon after the massacre of orphans and monks, Jon was transferred to the Military Assistance Command Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG). His commander was aware that Jon was distraught over the massacre and tried to get Jon to return to the States, apply for OCS, and take a commission. Jon opted to re-enlist, gain a stripe to Staff Sergeant, and remain in Vietnam. He completed one-zero (reconnaissance leader) training, and became involved in clandestine missions across the border of South Vietnam into Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam. His instructor in the course was Jim Shorten, who told Mike Evers that Jon was the best soldier in that group of new Recon Leaders.

“I met Jon in late 1970 when he came to B-53 for 1-0 school (Special Operations Team Leader Course). Jon came across as a country boy, well versed in the out-of-doors.

Toward the end of the course of training, I was his lane grader on the field mission. There were eight men on the team, all from CCN (Command Control North) at Da Nang, Vietnam.

“We were compromised in the field by the enemy, so I called for extraction. The first chopper came in and picked up 4 men via the STABO Rig. These are 120-foot ropes dropped from a motorized pully inside of the helicopter that we hooked to the top of our shoulder harness. The chopper then would pull us up through the jungle and fly us out to safety. The next chopper came in but there were 5 of us left, so Jon and I hooked up together on one rope. As we lifted up, we saw the enemy on the ground, Jon commenced to fire his CAR 15 at them causing us to go into a spin. Jon was having a great time while I was getting dizzy. I started shooting in the other direction to calm the spinning.

When we returned to base camp, B-53, the camp commander wanted me to make sure all the men were ready to be 1-0 team leaders. I told the camp commander, no way, these men need combat time under their belt before I would make then team leaders. I also told him that Jon Cavaiani was the only one who was close to being a good team leader, but SOG missions are a lot more dangerous than running missions in Vietnam, and they needed to be seasoned SOG soldiers first.”1

There were times when, on recon, the teams had to lay low and just let a large force walk past them. Being significantly outnumbered there was no wisdom in engaging the enemy in a firefight. On one occasion, Jon’s team came across an unexploded bomb that was designated as extremely sensitive. So as not to set the bomb off, the members of the team dropped all of their equipment, stripped down to bare butt nakedness and called for a helicopter extraction at a point well away from the bomb. Their radio call for extraction ended with, “Be on the lookout for the naked guys running to the PZ (Pickup Zone).”2

Later, on another recon mission Jon was wounded. He was sent to a field hospital for treatment and recuperation. After convalescing, he voluntarily extended his tour of duty in South Vietnam for another year.3

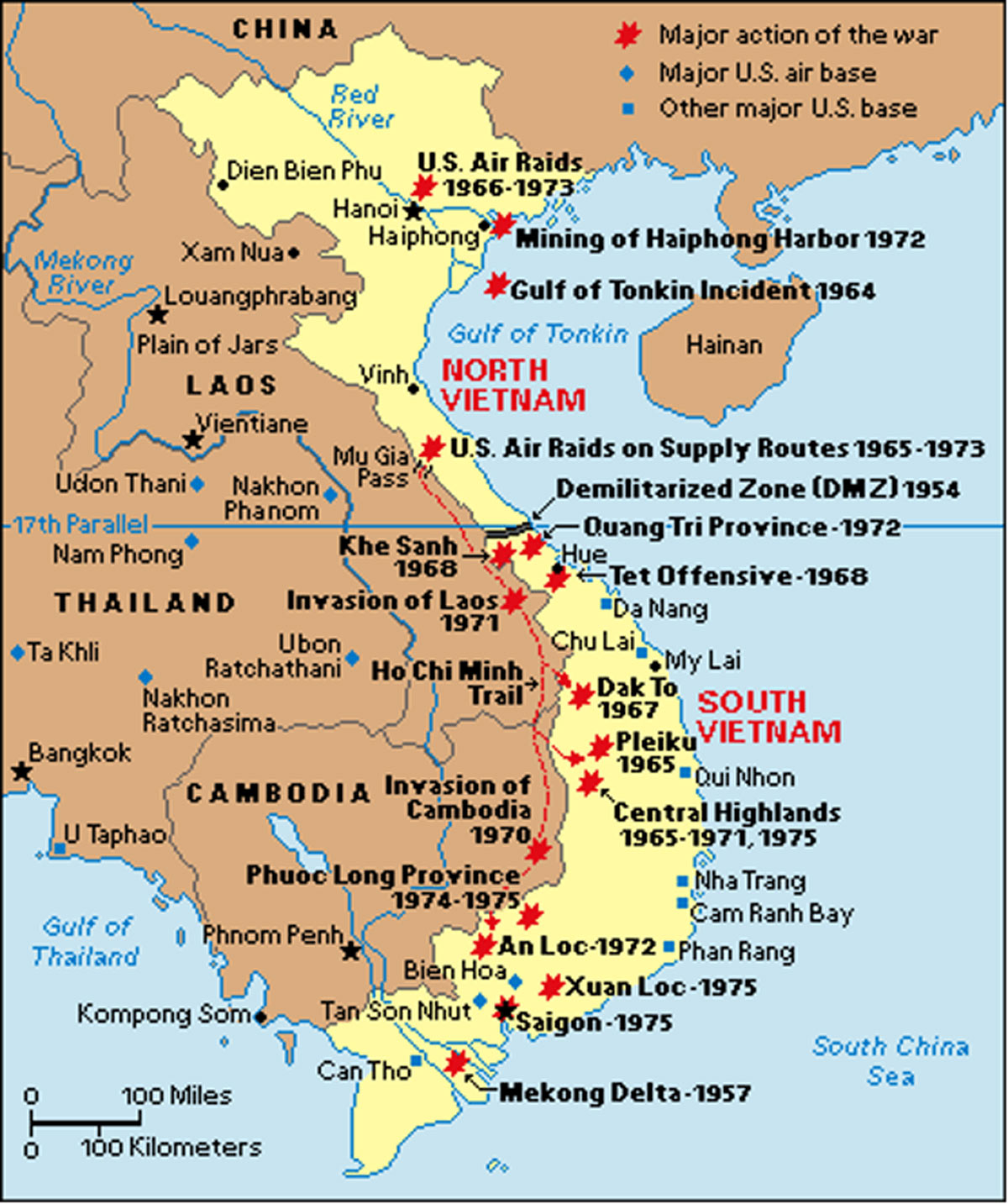

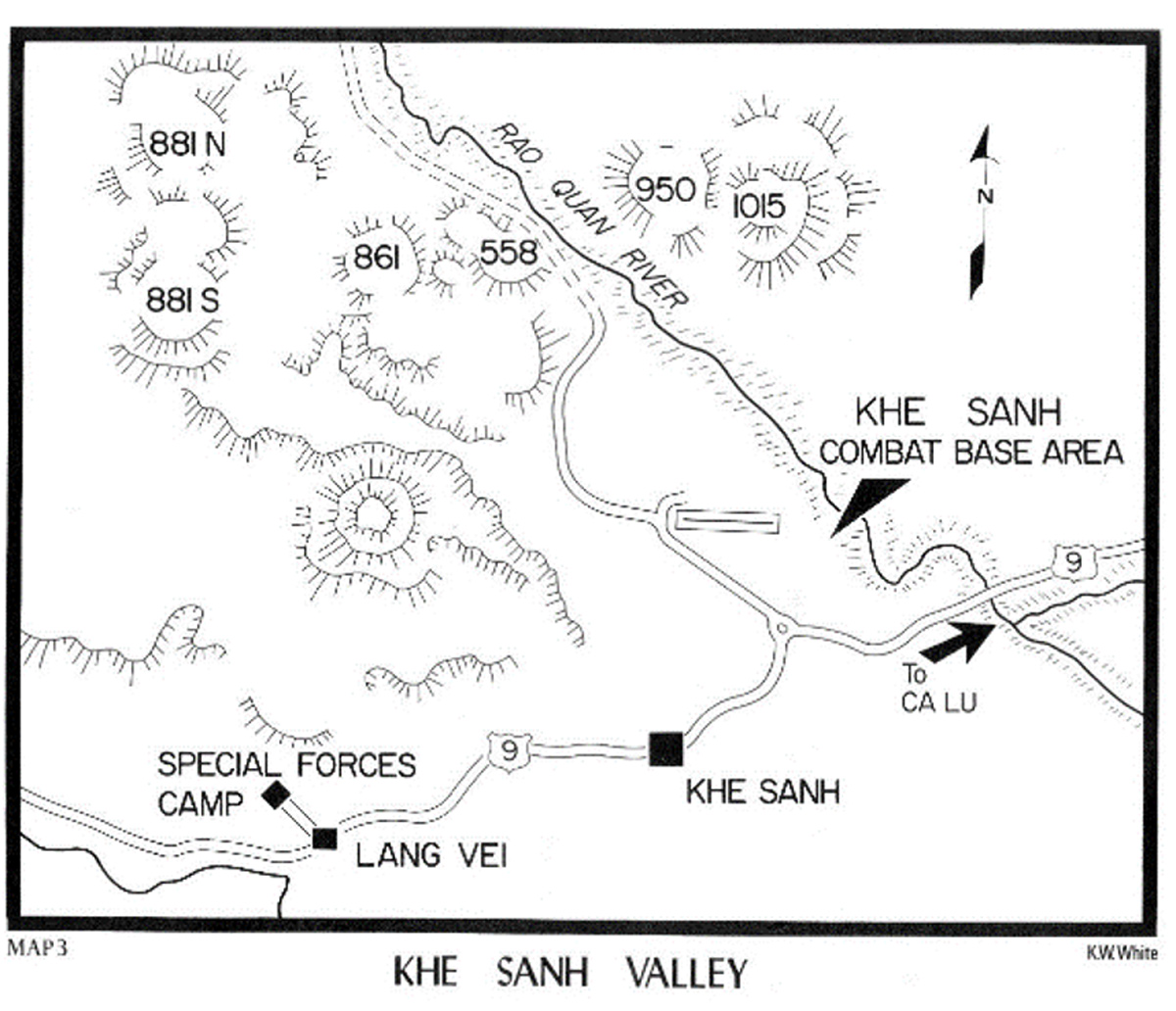

Jon’s next assignment was to lead a platoon at a remote outpost called “Hickory” which was near Laos where it meets what was the border of North Vietnam and The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). “Hickory” was perched just below Hill 1015 and above Hill 915 and was designated as Hill 950. Hills in Vietnam were measured in meters. A U.S. Marine unit had previously held the camp but determined it to be untenable. Prior to Jon’s assignment to Hill 950 (“Hickory”), Sergeant First Class Robert Noe had the dubious assignment of security responsibilities on that hill for a period of time. His comments, regarding the site follows:

“During the briefing before I assumed command of the defense of Hickory, I was told that when it is ‘socked in,’ the only fire support we could call on would be the 175mm Self Propelled Gun Battery stationed at Camp Carroll. These guns had a 20-mile (sic) range. When I plotted the distance from Camp Carroll, I discovered Hickory would be at the outer limits of the field of fire and thought to myself , who the hell would call in 175[mm] at this distance unless it was absolutely the last resort as any attack on Hickory would be in close, I mean Very Close, so any thing (sic) being fired from a long distance would not be that effective or precise for the needs of anyone defending such a small spot.

Often while on Hickory, I would look to Hill 1015, realizing it gave outstanding indirect fire onto Hill 950 and could not for the life of me figure out who the hell would occupy the lower hill, giving any advantage to the enemy if he were to occupy 1015. Little did I know that the Marines had lost 950 for the same reason and later SOG would also. During my stay, I kept all my mortars directed toward the top of 1015 and conducted random firings on it and over the other side and other areas on 1015.

Once Khe Sahn fell to the North Vietnamese in June of 1968, Hickory was a [solitary] very small dot on the map and deep in enemy held territory and anytime the enemy wanted it, they could take it, there are many times the hill was completely ‘socked’ in by low clouds and there would be no air support and you couldn’t see crap, much less hill 1015 where the enemy would surely position themselves to take Hickory. The enemy could lock down the Americans on Hickory by indirect fire, walk down 1015 and across to Hickory.

To me, it was just a bad place to be, a bad, if not impossible hill to defend, but that is the way it was. My tour on Hickory was June thru mid-July 1970.”4

Hill 950 or Hickory Hill (formerly named Lemon Tree) was located north of the abandoned Khe Sanh Combat Base. It was CCN’s top secret radio relay outpost atop of hill 950 established to observe enemy movement and monitor and relay radio transmissions from SOG teams’ operating in Laos. It was the final allied presence in the northwest South Vietnam after the siege of Khe Sanh during the summer of 1969 (Captain George R “Randy” Givens of CCN was given the mission of re-establishing Hickory as a CCN radio relay site, the site also housed the Army Security Agency’s Top Secret “Explorer” system and was monitored by two ASA personnel) until it was finally abandoned on 5 June 1971 when it was over-run by enemy forces. Jon Cavaiani was the Security Force Commander that fateful day, putting up a fierce counter-defense for two days.

Author’s note: On 4 June 1971 Captain Valersky was the ASA officer responsible for the operation of the Explorer system and he had two readers on site with him. Jon Cavaiani was the person responsible for security of that three-man team and the top-secret equipment. Cavaiani had a few other Green Berets, and about 60 Bru Montagnards for which he had leadership responsibility.

Hickory Hill (950), near Khe Sanh and the DMZ (The Assault on Hickory Hill: Noe)

Author’s note: The following account of the battle of Hickory Hill is a compilation from numerous sources to include: Interview notes presented by Pete Laurence; “The Assault on Hickory Hill – June 1971” as it appeared in the Special Forces Association’s Fall 2013 edition of periodical The Drop; Living History of Medal of Honor Recipient Jon Cavaiani video; Interview with Jon Cavaiani by Pritzker Military Museum; Library of Congress; BOARD OF INQUIRY: SGT CAVAIANI; McKim, Keith; Vietnam: Green Beret SOG Medal of Honor Recipients; Yucca Creek Records, 2015; Medal of Honor recipients – Vietnam (A-L)”. United States Army Center of Military History https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SeTr-itHkc&authuser=0;

The National Museum; https://www.thenmusa.org/biographies/jon-r-cavaiani/; various obituaries regarding Jon; and the Citation as presented to MOH Recipient Jon Robert Cavaiani. No slight is intended toward any previous recounting of this battle, and we hope we have compressed the thoughts of many into these few pages. Additional citations presented as appropriate.

A saddle ridge connected the two hills of 1015 and 915 with a small rise in between designated as hill 950. These were about six kilometers north of Khe Sanh, a sight of several fierce battles, the most famous being The Siege that lasted 77 days before the Chinese New Year in January 1968. With a commanding view of the terrain for miles, the mission of the occupants was to conduct reconnaissance, maintain a radio relay site, and monitor enemy movement into South Vietnam.

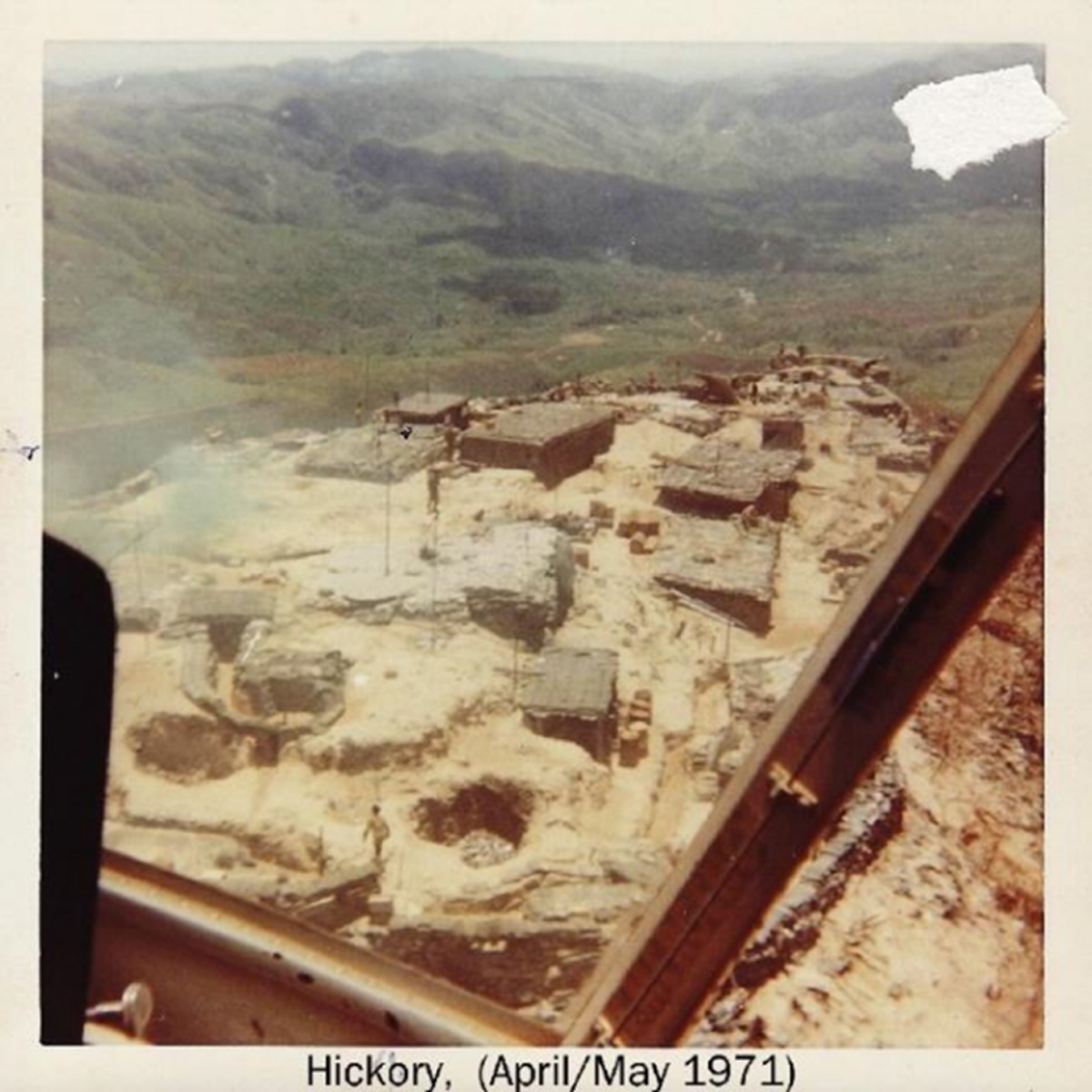

The tiny camp was about 20 meters wide and 50 meters long, clinging to a ridgeline like an old saddle on a bony nag. There were steep cliffs on two sides, a fairly sharp-drop-off on the third side, and on the fourth side a gentle upslope toward the peak of Hill 1015.

Vegetation along the rocky ridgeline consisted of trees (single canopy) with lush undergrowth. The vegetation was sparse enough to allow for unobstructed view of the valley floors on three sides. The camp was surrounded by rolls of concertina wire and a thick earthen berm. In the perimeter, there were tall radio antennas, a small helipad, and a few sandbagged bunkers for storage, sleeping, and protection.

The purpose of the tiny outpost located within enemy held territory was to monitor movement of enemy forces into and out of south Vietnam. Sophisticating sensing devices enabled a small team of Americans to monitor the sensors, read the data coming into the “Explorer” system and report findings to higher headquarters. Captain Valersky was the senior individual of that team and he had two readers, Specialist 4 Robert Garrison, and Specialist 4 Walter Millsap.

Jon and his platoon had responsibility for providing security for this team and for ensuring that the highly sensitive equipment of “Explorer” did not fall into enemy hands. The Russians and Chinese Communists had been trying for years to get this technology and would have paid a hefty price to North Vietnam officials for the capture of one of these systems.

When Jon arrived, the camp was in desperate need of much work to fortify and strengthen its defenses. Jon called for and received a team of Seabee’s (US Navy term for the Combat Engineers) to assist with fortifying the small encampment by replacing concertina wire, rebuilding the berms and bunkers around the small encampment, and reinforcing perimeter barriers. With Cpt Valersky’s calls to his higher headquarters a team of army engineers also came to help fortify the bunkers and berm around the perimeter, but for some reason the request for more concertina wire was not honored. All of this in June 1971.

Hill 950 – Hickory Hill – After Jon and his crew fortified the hill.

Jon’s “Pack” of warriors responsible for securing the listening team and the position to which they were assigned consisted of Sgt Robert Jones (John Robert Jones), Sgt Roger Hill, SGT Ralph Morgan, Sgt. Larry Page—all Special Forces qualified; a forward observer, 2nd Lieutenant George “Skip” Holland (attached from A Battery, 8/4th Field Artillery) and finally about sixty Bru Montagnards. The forward observer was there to communicate with artillery support units and call for artillery fire as needed. A significant problem was that Hickory Hill was at max range for supporting artillery fire. Significant artillery fire support was unlikely, and gunships were a poor option due to time on target and quite often, limited visibility.

The Explorer team reported significant movement of men and equipment coming from the north and moving south. These reports were either ignored or disbelieved, for no interdiction was taken by U.S. or South Vietnamese forces. After about one month, the team on Hickory had strong indications that the enemy had plans to attack and take the hill as they saw significant enemy activity in the area.

Despite being at an elevated location, or perhaps because of the elevation, fog, at times, would set in limiting visibility. The morning of 4 June 1971 was such an occasion. During the night, a heavy fog had limited visibility around the perimeter. Even when using night vision goggles designed to see in limited light – such as starlight on a moonless night – the visibility was almost nil.

Despite being at an elevated location, or perhaps because of the elevation, fog, at times, would set in limiting visibility. The morning of 4 June 1971 was such an occasion. During the night, a heavy fog had limited visibility around the perimeter. Even when using night vision goggles designed to see in limited light – such as starlight on a moonless night – the visibility was almost nil.

That morning the fog was reluctant to burn off as if wanting to hang over the hill like a blanket of fluffy snow. The winds were too light to move it away and the sun was slow in dissipating the mist. Sgt Roger Hill and three others were outside of the perimeter checking security around the lower helipad. Visibility began to improve and that is when they began receiving small arms fire. NVA forces atop Hill 1015 started firing rockets down into the area. Sgt. Hill was wounded in the hand.

Ralph Morgan grabbed his M-16 and began returning fire to provide the four men opportunity to rush back into the perimeter. He rushed to an M60 machine gun that offered greater suppressing fire against the enemy on Hill 1015. Sp4 Millsap manned another machine gun and began to place fire onto the hill and saddle ridge. He then assisted a wounded officer and protected him when a rocket round exploded nearby.

In the early hours of the battle, Cpt Valersky, 2nd Lt Holland, Specialist Millsap, and Sgt Hill were wounded.

Sgt. Roger Hill from Jon Cavaiani’s picture files.

As visibility improved in the morning light, the men inside the perimeter of Hickory could see Chinese-made claymore mines facing them, placed just outside of the perimeter wire. The lifting of the fog allowed them to see, what appeared to be a battalion of enemy (700 plus in number) dug in only forty meters away!

On this day, the farmer from Ballico, California who had enjoyed working with local villagers in their farming endeavors, and who was trained to provide medical care and who had done so much for the indigenous people of nearby villages, would be required to do things he never dreamed of doing. He would have to fight for his life and for the lives of his fellow Special Forces members, and for the people of the Montagnard villages who he had grown to love.

The battle was fierce! The green clad enemy were scampering, firing, and charging ahead in a mélange of terrifying assaults. Some of the enemy had gained the ridge above the camp and this high ground allowed them an unobstructed view of about seventy percent of the camp. Those on this high ground rained direct fire down onto the camp.

Rocket propelled grenade (RPG) launchers poured rockets into the perimeter. These also included B-40’s and 2.75 rockets, as well as rifle and machine gun bullets. The rounds peppering down limited the Green Beret men and their indigenous mates from maneuvering into better positions to gain advantage and return well-aimed fire.

(Later in life Jon would reflect, saying; “I couldn’t outrun ‘em, so I had to fight ‘em!”). And fight he did.

Jon immediately jumped to the .50 Caliber machinegun and began firing at the claymores to neutralize them. This also prevented an all-out rush by the enemy. The .50 Caliber quickly overheated due to the rate of fire, and Jon had to stop to adjust the headspace and timing. As he was doing so, Specialist Milsap, the ASA reader stepped up and asked if he could man the .50 caliber weapon. Jon asked if he had ever fired a .50 caliber machine gun and Milsap responded in the negative, “But you’re a Green Beret, you can teach me in three minutes.”5

Milsap was a large man who wore coke-bottle glasses, but Jon quickly instructed him on how to operate and fire the weapon and told him to keep the thing pointed at the enemy. As he then turned the big gun over to Milsap, he realized what the young soldier had done; he had essentially sent a message to Jon to get back to commanding the defense of the hill. Jon raced from position to position. It was doubtful that Jon knew at the time, but it mimicked the actions of Captain Roger Donlon on 6 July, seven years earlier, at Camp Nam Dong. Captain Donlon was the first Army Medal of Honor recipient of the Vietnam War.

At each position he quickly assessed the men, their supplies, and their medical needs. As he moved, he coordinated air-support, provided medical treatment, re-supplied the men with ammunition, and encouraged them to keep fighting. He seemed to be everywhere, all at once.

At one stop he grabbed a M-79 Grenade Launcher and lobbed a dozen or more grenades at the scurrying enemy. Then he grabbed a M-60 machine gun and threw it up onto the berm; when no return fire was observed he rose, aimed, and fired. He repeated this move a few times, but on one such occasion his face was bloodied by shrapnel from a grenade. Still, he continued-on, ignoring any pain or discomfort.

Jon ran back toward the .50 caliber machine gun because it had stopped firing. As he approached he saw that the berm had been hit just in front of the gun and it had fallen forward. Milsap, a rather large man, was standing up hugging the gun and trying to pull it back into position. Jon arrived and helped him and then saw that Milsap had taken quite a bit of sandbag fiber and sand to his face. It looked as if Milsap’s face had been sandpapered. Milsap told him that he could not see. Jon reached up and took Millsap’s coke-bottle thick glasses off his face at which time Milsap told him “Ah, that’s a little better.” Jon asked if he had a second pair and Milsap told him they were located in his bunker, so Jon ran and got them. With replacement glasses Milsap once again manned the big machine gun.

At one point, Jon recalled that some of their ammunition was still near the helipad and exposed to the enemy. Braving a torrent of bullets and explosions, he led a few men to the helipad, and they pulled the ammunition into a bunker.

Then the enemy began zeroing their mortar rounds, which had been off target, into the camp showering shrapnel and debris everywhere. More than one-hundred mortar rounds impacted in the small camp.

Jon realized that the only way to get any relief from the barrage was to return counter-battery fire on the enemy mortars. He counted the number of thumps from the mortars on the hill which told him how many rounds had been fired (three). When the third mortar round exploded, during a brief pause in the explosions, he raced out with a stick and a compass to poke holes in the impact point of the last round. This effort would help determine a reverse azimuth on the enemy mortars lobbing rounds into Hickory. It was an expedient, not a precise, method. With this type of expedient direction and distance guide to help estimate the locations of enemy mortars, he directed the four-deuce (4.2in) and .81mm mortars at the enemy mortars. The process was a long shot, but the effort was successful in silencing at least one of the North Vietnamese mortars.

Jon was wounded several times, by shrapnel. The camp’s antennas had all been blown down, parts of the berm were destroyed, and a supporting Cobra gunship (an attack helicopter) had been blown out of the sky. Though they fought determinedly, fending off continuing assaults, the camp was pulverized. Nightfall was approaching. These conditions led Jon to a decision to have as many survivors as possible extracted by air.

The position had become untenable. Cpt. Valersky directed Sgt. Page to call for medivac, then rapidly changed the direction to full extraction. Page called the Special Forces Mobile Launch Team requesting immediate assistance. To Sgt. Page the call for extraction was a demand, but to a desk jockey sipping on a cold Pepsi in an air-conditioned structure, it was a request. Shortly they received a response from a voice on the radio to go ahead and prepare for extraction; choppers were on the way. Three helicopters were dispatched.

Cobra gunships and F4 Phantoms preceded the medivac helicopters and placed suppressing fire on the enemy positions. Two medivac helicopters rolled in, one being My Brother’s Keeper and the other Curious Yellow.

On the ground, Jon’s “pack of wolves” skillfully provided covering fire as Jon guided the choppers, one at a time, into the camp, to extract the men out of the camp. Just prior to climbing on board the first chopper, Cpt Valersky directed the destruction of the Explorer equipment and all sensitive items in the bunker. Jon directed Sgt. Page to do so, and Page immediately ran to the site and ignited the prepositioned thermite sheets fed by oxygen tanks that lay atop the equipment. The equipment in the bunker was soon reduced to ash, slag, and melted plastics.

As Warrant Officer Dave Hansen lifted off in Curious Yellow, some men were hanging onto the helicopter skids, but none-the-less, they got on board safely. While on the ground the chopper had taken a few rounds and shortly after liftoff a white smoke began to tail the chopper. Chief Warrant Officer 2 Steve Woods watched Curious Yellow as it left a trail of vapor. Woods aborted his descent into Hickory and followed the damaged chopper. Hansen was able to make an emergency landing and My Brother’s Keeper touched down nearby to take on all been on board Curious Yellow.

Later in the day, slicks (unarmed UH-1H helicopters came in and took a few more off of the hill, even as the battle still raged. Sgt. Page, Sgt. Morgan, and SP4 Garrison were included in those who were evacuated. Morgan later said that he tried to convince Cavaiani to leave the hill and leave the Bru Montagnards behind.

“[I] did not understand why they (Cavaiani and Jones) refused to leave because the Hill was going to fall. There was no way it could be defended any longer as . . . [I] was the last defender on the east, facing Hill 1015, fighting with a M-60 [machinegun]. Now there was nothing defending the saddle between Hill 1015 and Hill 950, and the enemy could just walk across… Cavaiani directed the helicopters that evacuated U.S. servicemen and indigenous Vietnamese who were fighting with them. But he remained behind. ‘That will tell you the most about Jon,’ Ralph A. Morgan, a sergeant in the Special Forces who served with Cavaiani on Hickory Hill, said in an interview.”6

For the eighteen defenders remaining on Hickory Hill the odds were estimated to be 23 to 1.7 At about sixteen-hundred hours a U.S. Air Force “Jolly Green Giant” helicopter was seen coming towards them out of Thailand. That chopper was more than sufficient to pick-up the remaining force on the hill. Jones, Cavaiani, and the Montagnards remaining on the hill could load as the helicopter hovered with the blades spinning and the ramp lowered near or on the ground on the backside of the hill.

But then, the chopper turned around and with only a brief message via radio turned and departed without final approach to Hickory Hill. Some write ups said that the Jolly Green Giant was called back due to inclement weather. In his interview with Pritzker Military Museum, Jon recalled that he could see the bird clearly, he was sure that the pilots could see the hill, and even as the sun set that day, Jon had no problems with visibility. It was a clear afternoon.

The pilot, with seemingly tears in his voice, had told Jon that the mission to pick them up was aborted; the pilot and crew were under threat of court martial by the commander who called off the recovery craft. A “territorial commander” had called for the chopper to “cease and desist.” That commander’s feelings had apparently been hurt, because no one had asked his permission for the helicopter to enter “his space.”8

Richard Whitaker and his team sat aboard several slicks ready to go in and extract the few men remaining on Hickory Hill. The blades were turning, and they were armed and ready. The craft never lifted off. The extraction mission was aborted, and no reason for the abort was provided.

Morgan had asked that he be allowed to stay with them, but Cavaiani, the ranking NCO, ordered him to leave, saying that he and Jones would remain with the Bru pack. The last chopper to leave the hill that day was full. There remained with Jon and Jones sixteen Bru Montagnards. As night was coming on, and with it the blinding fog accompanying it, there would be no more attempts at extraction from within Vietnam.

Jon and his fellow soldier Jones could have been on one of those loads that departed Hill 950 that day. The Americans could have left the Montagnards to fend for themselves and then escape and evade as best they could. But Jon chose to remain behind with his remaining few men. In an interview with Pritzker Military Museum much later in life, Jon essentially stated, in essence, that “Because my little people (Bru Montagnards) bleed just like I do, I was determined to remain on the ground to help them.”9

As daylight faded into darkness and with increasing enemy fire, there were no more helicopters coming for further extractions. Eighteen residents of “Hickory” remained to defend the small bit of ground through the night.

Jon’s actions throughout the day had led to the evacuation of most of his men and now to a prolonged defense of the outpost with but a few men. It seemed immanent that an overwhelmingly larger enemy force was sure to annihilate those who remained on the ground atop Hickory. Still fighting for their lives were sixteen Montagnards, another Special Forces Sergeant from Texas named John Jones, and Jon Cavaiani. Jones may have tried to make a joke of the situation by saying, “This is our Alamo.” But if he did so it was unlikely that anyone laughed.

In an attempt to hold onto the back half of the camp, Jon crawled to the front half and prepared a booby-trap to greet the next assault wave. He rigged a 105mm artillery round so that he could detonate it at the appropriate time. He placed mortar rounds and other equipment around it so that these too could cause harm and/or be damaged beyond use by the enemy. Any remaining equipment that might be useful to the enemy, he destroyed using thermite grenades.

Then, for the first time in Jon’s combat experience, he strapped on a steel helmet. He then issued more ammunition and encouraged the men to dig a little deeper. It was his intent to make it very costly to the enemy when they again assaulted. Perhaps it was “Alamo,” Vietnamese style.

At about eight o’clock in the evening, just as the sun was setting, the enemy renewed its assault on the small camp. The few men remaining in the camped braced themselves and returned fire as best they could. The odds were about twenty-three to one in the NVA’s favor. A front row of enemy fired automatic weapons while a second row lobbed grenades over their heads as they advanced. The Montagnards and two Americans returned fire, but the advancing enemy breached the wire, crawled up and over the berm and swarmed into the front part of the camp.

That was when Jon detonated the artillery round creating a huge crater and literally blowing several of the enemy off the ridgeline. With that huge blast the enemy retreated. During this lull, Jones rose from his position near the mortar pit and scampered back to Cavaiani’s position on the western perimeter. They then moved to the remnants of a bunker to try and consolidate their efforts.

However, about two hours later, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong renewed their assault. At first, they came in groups of about ten or twelve, moving more cautiously than before in case there were more booby-traps. As their confidence grew, they began to send wave after wave of about fifteen attackers every fifteen-minutes or so.

Because Jon had set the few remaining men in positions that created a crossfire along the bottlenecked entry into the back part of the camp, many enemy soldiers were killed and wounded. It was a long night of human wave assaults. It was danger close. After each assault, during the few moments of respite; wounded would be tended to, and ammunition redistributed.

There were no bombers or fighter aircraft available for support. However, Jon was in contact with a Stinger orbiting overhead. It was a C-119 with a Gatling Gun that would put bursts of 7.62 rounds on the perimeter. The Stinger also dropped illumination flares. The flares gave an eerie effect to the life and death drama.

Jones manned the radio communications, while Jon and the Montagnards fought gamely. Jon used the machineguns and focused the direction of fire of the remaining few. Through the night they withstood the incessant barrage of rocket fire, mortars, and small arms fire; they beat back wave after wave of charging enemy.

Shortly after 0500 hours, but just prior to the NVA breaching the perimeter in mass, Jon and Sgt. Jones passed the word to the Montagnards to try and escape off the mountain. Knowing that they could not hold out much longer, Jon ordered the Montagnards to “di di mau” (boogie out of the camp) and had Jones call for the Stinger to fire on their position. As they all headed over one of the steepest slopes of the hill, Jon was shot in the back near the spine. His men came back to help him, but he ordered them to go. He covered their escape with blazing M-60 machine gun fire.

When the enemy took control of Hickory. Jon had Sgt. Jones contact the Stinger and have them fire on the camp again as they dove into a sandbagged bunker. For some unknown reason, the Stinger did not fire on the enemy swarming the hill. The fire power of the Gatling Guns on board the stinger would have likely annihilated the swarming NVA and allowed Jones and Cavaiani to escape. With no Stinger support firing directly on the hill, the two Americans huddled in the small bunker, about seven-by-seven feet in size, and waited. The bunker had a thick sandbagged cover and only one trench-like slit for entry and egress. Patiently they waited for the inevitable moment of their discovery, preparing to kill silently with their knives or more likely, to be killed by the enemy.

The enemy death toll was somewhere between three and four hundred. The North Vietnamese were initially so excited about taking the hill that they failed to search the bunkers. But then, two of them came to the access and entered one at the time. Jon let the first man go past him, then swiftly killed the second man with his Gerber. Jones took on the lead man, but in that struggle, despite killing the North Vietnamese soldier, shots were fired, which alerted the enemy above. One of these two NVA soldiers was the son of a NVA Colonel. Jon would pay dearly for that later.

Hearing the rifle fire, the enemy soldiers above reacted quickly. A grenade was thrown into the bunker, and it was deafening. Jon was wounded, again, by the grenade’s shrapnel, and Jones was wounded severely. Realizing that they were surely trapped, Jones crawled out of the bunker to surrender, but he was killed immediately by a North Vietnamese soldier. Another grenade was tossed into the bunker to finish off anyone else inside. Only Jon remained and the blast deafened him and caused more hemorrhaging. It also destroyed the last line of communication for Jon back to his friends at it tore apart their one remaining radio. Up until that time, Americans in the Stinger above and back at Special Forces Headquarters had been monitoring the entire battle, hearing everything up to the final grenade.

Hours later, after morning fog had burnt off, reconnaissance aircraft could see the outpost and confirm that it had indeed been overrun; Hickory Hill was now in the hands of the enemy.

Per records of the Library of Congress under the heading of BOARD OF INQUIRY: SGT CAVAIANI, JON R., JONES, JOHN R., WITNESS STATEMENTS10 the following gives a clearer picture of the chaos in which Jon Cavaiani and John Jones found themselves.

On 3 August 1971, a Board of Inquiry was convened to determine the status of Sergeants Cavaiani and Jones. Witness statement had been gathered from U. S. personnel and Montagnard personnel who had been evacuated from hill 950. These were presented to the board and reviewed. A document dated 9 June offers that 11 CIDO’s were interviewed and that nine of the eleven had seen SSG Cavaiani under intense small arms fire and B-40 rocket fire. One CIDO stated that he saw SGT Jones lying on the ground near a mortar pit. None of the CIDOs could confirm the death of either Cavaiani or Jones. Several of the statements appear below:

Major Herold B. Quarino provided the following:

“Last contact with US personnel was established 0505454 (sic) Jun ’71, at that time the radio operator stated in a whisper, ‘They are two feet from me, out.’ A FAC [forward air coordinator] came on station 0506034 (sic) but could not establish radio or visual contact at that time. On 051250 – 051305H Jun 1971 a UH-IH flew a VR [visual reconnaissance] over the site with good visibility and observed no personnel or bodies. On 051525H a UH-1H flew within 150ft of the site. On 051730 an attempt was made to insert a rescue force on the site. The attempt was aborted due to heavy enemy ground fire. The E&E [escape and evasion] route was not flown on 06 Jul due to unworkable weather.”

Larry Page’s statement reads:

“When I left the site Sgt Jones and Sgt Cavaiani were in good condition. Sgt Cavaiani had suffered a minor frag wound to the left side of his face at approximately 1700hrs. Both men were located at the west perimeter organizing their people for extraction this time was approximately 1630. (sic) [pen and ink correction made to reflect hours and initialed].”

Roger Hill’s statement reads:

“The last time I saw SGT Jones, and SGT Cavaiani was on or about 1130 on 4 June 1971. Both were in good health and spirits. They were both in the process of re-organizing troops and ammo, while also taking care of the wounded.”

A transcription of Ralph Morgan’s statement follows:

“At approximately 1945 on 4 June I departed the radio relay site, on the last extraction of the day. At this time, I saw SGT Cavaiani and SGT Jones both in good health. However, SGT Cavaiani had suffered a fragmentation wound to the face and both men were in low spirit. I was the last American to see either of these men.”

A statement taken by a U. S. Army officer from a Montagnard soldier named Tung states (through a translator):

“…CMD Tung states that he witnessed one American with a mustache (Sgt Cavaiani) being shot by an NVA, from close range, with remaining American at the vicinity of a mortar pit, receiving a heavy volume of SAF(small arms fire) and hand grenades.’’

A different soldier named Tung wrote his own statement and signed his name in cursive:

“At 0400 hours I was in a bunker on the west side of the radio relay. I saw SGT Cavaiani fire his CAR-15 at an NVA soldier and kill him. Another NVA, approx. 3 meters from SGT Cavaiani fired an AK-47 and I saw SGT Cavaiani fall to the ground. At approx. 0500 hours I saw SGT Jones crawling to the mortar pit in the center of the perimeter. The last time I saw SGT Jones he was near the mortar pit and receiving many hand grenades and small arms fire. The hilltop was covered with fog, and I could not see well. I left the hill at 0510 hours.”

Yet another CIDG soldier named Ai-Ta provided the following through an interpreter about what he observed on the morning of 05 June 1971:

“From his bunker on the western perimeter, CIDO AI-TA OBS one American lying on the ground near a mortar pit inside the perimeter. He observed a possible B-40 rocket, or mortar round explode 2 to 3 feet from the American. CIDG AI-TA also observed one other American lying near the western perimeter, and SAF [small arms fire] fire being placed on and around the American.”

A CIDG soldier named A Van provided the following:

“At 0530 hours 5 June 1971 I saw enemy advancing and saw SGT Cavaiani kill or wound 25-30 enemy with M-60 MG fire. Approximately 2 minutes later SGT Cavaiani was wounded by a B-40 rocket and was screaming. A second B-40 rocket hit the position and there was no sound from SGT Cavaiani. The last time I saw SGT Jones he was in the mortar pit. I left the hill at 0545 hours.”

From one named KINH:

“At 0530 hours 3 [sic] June 1971 I saw enemy advancing and SGT Cavaiani fired on them with the M60 MG killing or wounding 20-30 enemy, SGT Cavaiani continued to fire for 1-2 minutes. A B-40 rocket was fired into SGT Cavaiani’s position and I heard him scream. I saw SGT Jones lying two meters from the mortar pit. At 0545hours I left the hill after yelling for SGT Cavaiani and getting no answer.”

Similar reports were rendered by CIDG personnel A-Vat, Phong, Xang, Quang,Nui, Va-Chuai, Quai, and A-Cum. These individuals reported that it was still dark and foggy when they departed the hill about 0540 hours.

Photo of Hill 950 0n 5 June 1971 taken by W.O. Dave Hansen during Recon Flight to determine the extent of damage and ascertain the potential for locating U. S. personnel who might have survived the battle.

Having considered the statements presented, the board prepared a document dated 20 August lending closure to the investigation. The document bears the concurrence the Commanding General, United States Army, Vietnam that Sgt. Jon R. Cavaiani and Sgt. John R. Jones should be listed as missing in action.

Soon thereafter, for having held out so valiantly, for having saved so many lives of his men, and for having killed so many of the enemy, Jon was recommended for the Medal of Honor. Cpt. Valersky submitted the recommendation as a posthumous award.

Sadly, for Sergeant John Jones the board was incorrect. However, the board was correct in Jon Cavaiani’s case, for he was not yet dead. After the last grenade, Jon had played dead which wasn’t too difficult at that point. A North Vietnamese soldier had entered the bunker and checked him out, then threw Jones’ dead body on top of him. The tarp paper that lined the bunker was then set on fire. Using his willpower, Jon stayed inside, as long as possible, withstanding the choking smoke and boiling heat that seared his hands, back and face.

Forced by the unbearable situation, he finally crawled out of the bunker to face whatever fate awaited him. Fortunately, the group of enemy soldiers that had burned the bunker had moved on to other interests. This allowed Jon time to crawl into yet another bunker.

The “new” bunker had been partially destroyed by a rocket, so Jon hid among the debris. He was still determined to eliminate any enemy who might find him. As daylight began to appear in its foggy form, he watched legs pass back and forth for what seemed like an eternity.

Eventually a soldier entered the bunker and began to probe around. When he pulled the cover off Jon, he was shocked and too surprised to speak or yell. Jon’s knife went forcefully into the man’s heart. Muffling the man’s gurgling, Jon tried to pull the knife out, but it was stuck in the man’s sternum. As he pulled, the burned meat of his hands started to rip. Leaving the knife protruding from the man’s chest, Jon crawled under a bunk that had survived the night, then passed out.

When Jon came to, there were two enemy soldiers in the bunker. Again, Jon feigned death. One of the enemy soldiers sat on the bunk and reached down, grabbed Jon’s leg, and raised Jon’s leg by the ankle. The man turned Jon’s foot slightly, studying the size of his boots perhaps for fit on his own feet. It must not have been a good fit, for the man dropped the leg and continued rummaging in the bunker. He left shortly thereafter.

Summoning all his strength, Jon stealthily crawled out into the fog, slithered over the earthen berm, and down the steep sides of the mountain. Shot, torn by shrapnel, badly burned, yet scared enough to overcome the pain, he headed through the jungle toward Dong Ha.

“By this time, I was crazy. And just did not want to get caught,” Jon would later recall in an interview with Soldier magazine.11

Deafened by the grenade, he moved only at night. He tried to re-call and use the Escape and Evasion training received in the Special Forces course at Fort Bragg (called SERE: Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape). Hunger, sleep deprivation, and self-reliance had been part of that training; but now it was real – this was his life that he was fighting for – not just a medal or certificate. He reflected on his life on Ugo’s farm. To survive, chores needed to be done. There was no choice.

During Jon’s interview at the Pritzker Military Museum interview, he told the audience that, and we paraphrase here, he learned that when eating insects, it is best to first remove their legs. Otherwise, the critters would try to crawl back out.

By moving only at night, he avoided the enemy over the next few days, covering several kilometers, and finally approaching Camp Fuller. He elected to await daylight so as not to be mistaken for an enemy saboteur/sapper. But while waiting for daylight to make his presence known, a Vietcong soldier who had been tracking him and others who had crawled down the slopes of Hill 950 stumbled upon him. The Vietcong soldier looked to be about sixty years old and was shaking as he pointed his rifle at Jon. Because of the man’s nervousness, and because Jon was exhausted, he did not resist. At gunpoint, Jon was marched all the way back to near Hickory, and to enemy interrogation in a Vietcong encampment. The march back was not easier, but it was faster in the daylight.

Jon imagined what might be in store for him. He recalled an earlier time when he had found the remains of a Special Forces friend who had been captured by the communists. Found two days after the capture, the body was still warm but dead. They had popped the soldier’s eyes, perhaps with sharpened bamboo sticks that lay nearby and bloodied, gutted his intestines so that they were still attached but dangling outside his body. There were signs of other grotesque indecencies to include severing his penis and testicles. All surely culminated in a most agonizingly slow death.

Near Hill 1015, Jon’s arms were tied behind his back and a T-Bar was slid through so that he was hoisted off the ground. Spasms of pain coursed through his already torn and bloodied body. They beat him and pounded him as he hung suspended. Each blow to his body brought excruciating pain, not only to the targeted spots, but to his arms and shoulders as he bounced up and down in his suspended state. But all Jon would provide was his name, rank, and serial number. After long and excruciating amounts of abuse, Jon still refused to provide the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) interrogator the desired response. The interrogator then had five Bru Montagnards brought forward. These were five of the men who had served with Jon at Hickory. They, too, had been captured. The interrogator told Jon to respond to all questions or he would kill each of these men in turn.

Jon responded with, “Cavaiani, Jon, Staff Sergeant…” when he was cut off by the noise of a pistol being fired. As Jon started to speak, the Interrogator had casually raised his pistol and shot the nearest Bru Montagnard. Jon said, “You can kill them all and me, too, but you still will get nothing from me.” The NVA officer again raised his pistol to the temple of a second Bru and pulled the trigger.

SSG Jon Cavaiani reporting to President John F. Kennedy on 12 December 1974 after being awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Jon remained silent. Seeing that this method was not making Jon talk, the North Vietnamese officer had the beating resumed. In defiance Jon said, “My grandmother hits harder than that.” They then went to hitting him with rifle butts, pistol whipping him, and kicking him. In doing so they fractured three vertebrae in his neck and three in his lower back. Repeatedly, he fell unconscious from the blows.

Eventually, Jon was lowered to the ground where, after some time, he regained consciousness. When he did so he noted that his facial wounds and hands had been rudimentarily bandaged and that he was dressed in an American flight suit. He was then forced to stand and walk in a specified direction. It was when they approached a village below the Vietcong encampment that he realized that he was to be paraded through villages as if he were a pilot of a US jet that had been shot down. The bandages were designed to show that proper treatment was being provided.

“So, this political officer (North Vietnamese) had the villagers all riled up (because there had recently been U. S bombing raids in the area). – The political officer had announced to the villagers that he was bringing a U. S. pilot though their village – a pilot who had recently bombed their region – They all had their sticks, and they were going to beat this pilot as he was paraded through their village. But the political officer screwed up because he removed the flight helmet that had been placed on me. Well, this little old grandma got right up into my face, and all of a sudden, she let out with a loud, ‘Boxie (sic) Jon!’ ‘She had recognized me.’ Jon had helped deliver four babies in that village and one of them was the grandma’s grandchild. Well, the political officer lost face (with the villagers.) because he had lied.”[45]

Author’s note: Lying and falsification are unacceptable behaviors in most Asian cultures and brings significant shame upon the person and the family.

Local farmers joined in waving to him and calling to him. They recalled how that “Bác S? Jon” had helped them with their farming techniques. The villagers knew how he had cared for their children and had delivered some of them into this world. They knew that he was not a jet pilot. They knew him as a caring and compassionate farmer and medic. That he had been in the dull position of regional veterinarian was cause for the villagers to have fond remembrance of him. Their calling to him on that day may well have saved his life.

With the NVA political officer having lost face for putting on a pretense, Jon was spared. As he departed the village for a new, but unknown destination, Jon saw the Political Officer one last time – he had been tied to a tree.

Jon marched on foot across the DMZ. After a time, he was placed in the back of a truck for a short distance and then placed on a train for the long trip to Hanoi. While on the train Jon recognized some of the Bru Montagnards who had been with him on Hill 950. There was hardly a handful. He quietly whispered to one but there was no response. He then asked why they would not speak with him. One quietly responded, “The train has many eyes and ears.” About 20 miles short of Hanoi, the train stopped and the Montagnards who had served with him were taken away; hopefully to a prison camp for South Vietnamese but probably to a re-education and indoctrination camp. It is likely that none survived.

As the Montagnards were moved off the train, Jon saw a Vietnamese man who he knew to be an interpreter on Hill 950 step from the train and, discarding his South Vietnamese Army jacket, donned a North Vietnamese jacket bearing the rank of Lieutenant. He was both welcomed and saluted by the North Vietnamese. Bile rose in Jon’s throat and he vomited.

Over the next twenty-three months, he was held in such infamous prisons as Plantation Gardens, The Zoo, and the Hanoi Hilton.

To the Army Jon was presumed dead but listed as MIA. To some of his hopeful family and friends he was missing. To himself he was just worn down, aching, and tired – but happy to be alive. His wounds were crudely bandaged, but the bullet lodged in his back was not removed. As for the numerous fragments of shrapnel in his flesh, he was forced to sharpen a bamboo stick and remove as many of them as he could himself. Some fragments, fibers, rocks, and sand would have to wait for extraction at some later date or just stay in place.

Endnotes:

1. Shorten, Jim; Jim Shorten (Jones) <theemeraldsea@aol.com> Date: Mon, Aug 15, 2022, 4:58 PM, Subject: Re: SGM Cavaiani To: john@johnsiegfried.com <john@johnsiegfried.com> Forwarded to Michael Evers evers.michael.b@gmail.com Oct 6, 2022 for insertion

2. Pritzker, Op Cit

3. Living History of Medal of Honor Recipient Jon Cavaiani; interview at: https://youtube.com/watch?v=4SeTr-itHkc&feature=share

4. Noe, Robert L.; et al; The Drop: “Assault on Hickory Hill,” June 1971; Special Forces Association Fall Ed.; Fayetteville, NC; 2013

5. Pritzker; Op Cit

6. Langer, Op Cit

7. McKim, Keith; Vietnam: Green Beret SOG Medal of Honor Recipients; Yucca Creek Records, 2015

8. Pritzker; Op Cit

9. Pritzker; Op Cit

10. Congress, Library of; MANUSCRIPT/MIXED MATERIAL, BOARD OF INQUIRY: SGT CAVAIANI, JON R., JONES, JOHN R., WITNESS STATEMENTS (e-location at: https://www.loc.gov/item/powmia/pwmaster_76566/

11. Baldi; Op Cit; page 51

To paraphrase Willie Nelson, my heroes have always been Green Berets. Thank you for your sacrifices and mentoring.

DOL

When i was reassigned to ODA-762 in Jan ’83, a MSG NOE was team sgt. He was retiring and moving to Hawaii.