IVS Strove to Better Laos While War Raged

Jack Williamson (USAID), local leader Lao Chu (blue shirt), and paramilitary soldiers in front of a Continental PC-6 Pilatus Porter, Lima Site. (All photos courtesy of Frederic “Fritz” Benson via the University of Wisconsin – Madison Library.)

By Marc Yablonka

Hmong Daily News, Friday, September 13, 2024

https://hmongdailynews.com/ivs-strove-to-better-laos-while-war-raged-p739-154.htm, used with permission

Between 1956 and 1975, during the secret war, 384 soldiers of a different kind landed in Laos. Their holsters held no guns. They brought hammers, ploughs and textbooks. Their pockets were not filled with bullets, but with wide-ranging construction, farming, and teaching experience. They pledged at least two years, though some stayed far longer, to the International Voluntary Services, an offshoot of USAID, the United States Agency for International Development.

IVS, as it was commonly known, was a private voluntary organization “founded in 1953 to provide volunteers for international relief and development programs. Over its 50-year existence, this public-private partnership provided volunteers for 1419 assignments in 39 countries,” in a book co-edited by former IVS volunteers Frederic “Fritz” Benson, Gary Alex and Mike Chilton called A Legacy of America’s Global Volunteerism – International Voluntary Services (1953-2002).

In Laos, “the primary goal was training. All IVSers would teach themselves out of a job and turn responsibilities over to the Lao,” the book states.

The salary for doing so was $125 a month, according to Benson.

Air America C-130 evacuating Tai Phuan refugees and their belongings from Lat Sen on the Plain of Jars to the Vientiane Plain from Lima Site 276 in January 1970.

“The first volunteers arrived in 1956. This began a 19-year program [1956-1975] that included 384 volunteers. It was clear that IVS was engaging in a country with a serious conflict underway, and volunteers seemed committed to helping the effort to counter the communist insurgency,” the book adds.

That conflict spread to Laos from neighboring North Vietnam after 1962, when the Geneva Accords of that year declared Laos a neutral country. Soon, upwards of 30 to 40,000 North Vietnamese Army regulars were welcomed across the border into Laos by the Communist Pathet Lao cadres who had themselves been engaged in a struggle for power with royalists and neutralists in Laos.

The aim of the now united NVA and Pathet Lao was to move men and matériel through Laos down what came to be called the Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam, where their aim was to assist in the battle against US Forces.

The US was left with no choice but to deploy US Air Force personnel, sheep-dipped (the military term for plain-clothed), in a conflict that was orchestrated by the CIA with the assistance of Hmong hill tribes known as SGU (Special Guerilla Units), and airlines like Air America, CASI (Continental Air Services, Inc.), Southern Air, and Arizona Helicopters, who would mix missions of ferrying SGU fighters to and from battles against the PL, along with flying in rice and other staples supporting IVS, and USAID employees in their missions to bolster the lives of the people of Laos.

“Still, it is unlikely that any foresaw the scale of the conflict that was to develop and the destruction and loss of life that would ravage the country and engulf IVS in its own crises and controversies. Despite these developments, many volunteers served there and left with a feeling of accomplishment and with life-long friendships and attachments to the country,” the book informs readers.

Fritz Benson was one of them. He arrived in 1968, and IVS would be his employer for the next two years while the secret war in Laos raged on. He came for adventure and adventure is certainly what he got.

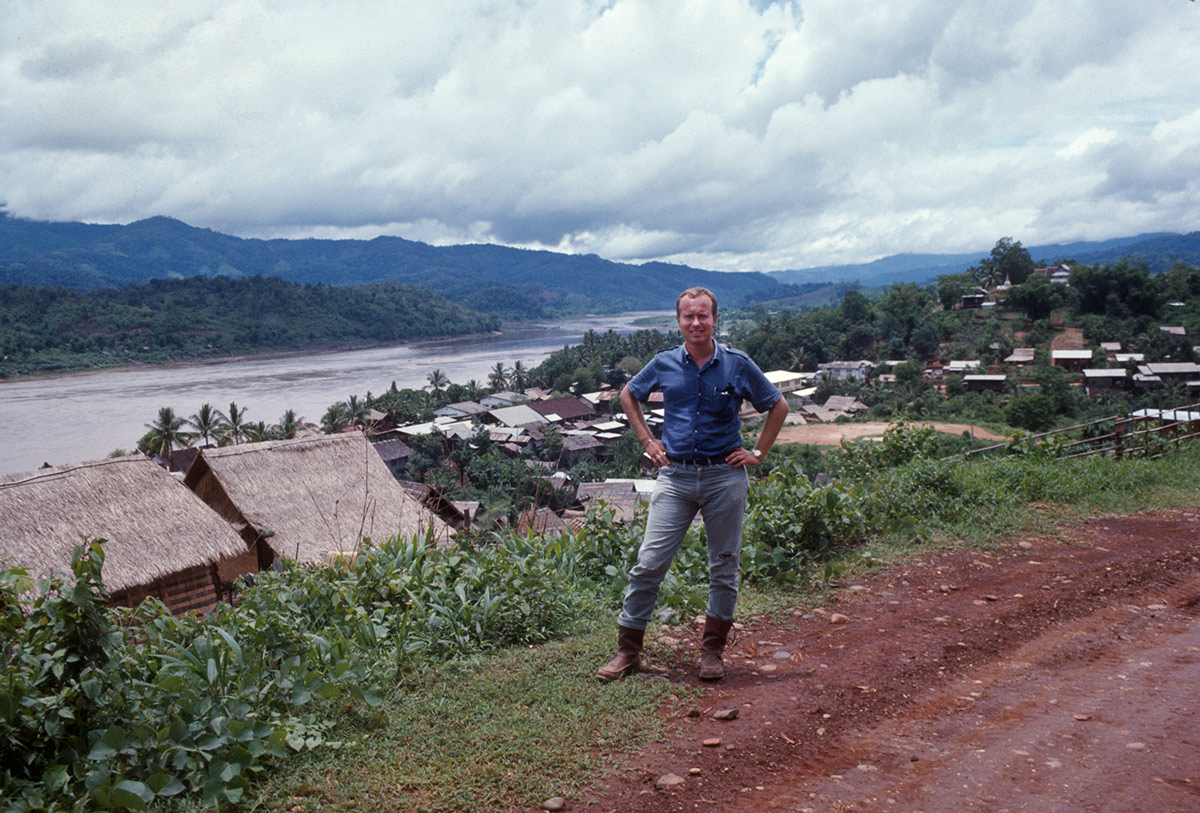

Frederic “Fritz” Benson, USAID Refugee Operations Officer at the time this photo was taken, at Ban Houei Sai at the Mekong River across from Thailand.

“I learned about IVS when I paid a brief visit to Laos in 1966 when I spent a semester at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok,” he told the Hmong Daily News.

While each IVS volunteer had a unique experience, Benson says, “What I did was representative of the wide-ranging and innovative activities engaged in by most IVS/Laos people in response to the local needs in the villages that welcomed them.

“For one year I was in Ban Thalat in rural Vientiane Province engaged in socio-economic research to identify what could be done to enhance the well-being of area villages. In my second year, I was assigned by IVS to do country-wide field work with USAID in refugee reporting,” Benson said.

Like all IVS personnel, Benson underwent six weeks of training in the Lao language. He also had one month of training in social-economic survey methodology in rural Sayaboury Province.

Hmong girl at Nam Hia village wearing ethnic clothes with headdress and silver necklaces.

Others taught English to lowland Lao and Hmong hill tribespeople. Still others performed agricultural work with a mind toward teaching the Lao and minority ethnic groups in the cities and villages throughout Laos from Vientiane in the south to Luang Prabang in the north, and hill tribes in the villages in between, how to be self-sufficient.

Beginning in the late 1960s, “The role of IVS changed based on needs and circumstances after completing urgent refugee resettlement. IVS then moved to longer term development objectives involving research and extension for important cash and food crops. Later, volunteer assignments diversified and became more urban-focused as conditions changed and rural areas became less secure,” according to A Legacy of America’s Global Volunteerism.

In 1960, early on in IVS’s tenure in Laos, during a coup d’état staged by Royal Lao Army General Kong Le, to protect them from harm, IVS volunteers were evacuated to Bangkok. Six months later, Gen. Le was ousted from power and volunteers resumed their work in Laos.

By 1962, IVS teams were positioned in major Lao provincial capitals including Luang Prabang, Sayaboury, Ban Houei Sai, and Pakse, according to the book, before being reassigned to rural areas.

Hmong family in Muong Phieng wearing traditional clothing.

IVS volunteer W. Wendell Rolston, a retired Indiana farmer recalled, “When I came to Laos, I hoped to better the educational, health, and agricultural programs, as well as to improve the living standards of Laos. We hoped to do this through a teaching and demonstration program, emphasizing the self-help process,” he told editors Alex, Chilton, and Benson.

But the burgeoning “secret war,” as it came to be known, often got in the way of what IVS personnel were sent to Laos to accomplish and endeavored to do.

James Malia, who served with IVS between 1967 and 1971, whose mission was to train Royal Lao Government forestry personnel in forestry inventory methods, told author Thierry J. Sagnier for his book The Fortunate Few: IVS Volunteers, “Significant change for IVS was precipitated when volunteers began to be killed—four Americans and two Lao assistants in a two-and-a-half-year period. Despite all intentions to the contrary, IVS was identified with one side in a civil war.”

“To those on the other side, we were part of the enemy and clearly marked by our white skin and round eyes. When shots were fired, IVSers were fair game. And since we were in the rural areas where the war was being contested, we were highly vulnerable,” he told Sagnier.

Reflecting on the dangers IVSers faced in Laos, Fritz Benson recalled, “I was transferred out of Ban Thalat for security reasons in July 1969.”

Still, IVSers did not lose sight of why they were in Laos. That was true for Malia as well.

“I had volunteered to do good works, to see some of the world, and to learn what I could,” he added.

Distribution of USAID/Ministry of Social Welfare supplies to Akha refugees at the paramilitary Team 5 village base, Chommok. Lima Site 345.

Like several of the males who volunteered for the IVS, Malia was a pacifist.

“As a practical matter, I also was completing my alternative service as a conscientious objector. I went to Laos excited and optimistic about what I would be doing. In retrospect, I also was naïve,” Sagnier tells readers Malia said.

IVS, like every organization that had supported the Royal Lao Government, left Laos in May of 1975, when, just as had happened one month earlier in neighboring Vietnam, Laos fell to the Communist forces.

Reflecting on her time with IVS, English teacher Merritt Stevens wondered whether she had done the right thing by volunteering for IVS.

“I have to admit I am truly not sure what I accomplished. Since Laos was taken over by the Communists in the mid-1970s and hearing that Lao people were being sent to [re] ‘education’ camps, tortured or killed, I feared the worst. What had I done? By teaching English, I may have put my students in harm’s way. It was a burden I felt for nearly 40 years,” Sagnier wrote Stevens told him in The Fortunate Few.

What allayed her fears for her students was put to rest when, while visiting Portland, Oregon years later, she was able to contact one of her former students.

“I learned that most of them not only survived the Communist takeover but are leading very successful lives all over the world,” Sagnier wrote she informed him.

Lao soldiers after an early morning attack on Ban Thalat by the Pathet Lao on 24 July 1969.

Though Fritz Benson’s tenure with IVS was over in 1970, rather than leave Laos he was engaged by USAID’s Office of Refugee Affairs to do regional work until 1972, whereupon he was transferred to USAID’s Refugee Operations Office in Luang Prabang, where he worked until 1974.

With all those years in-country and exposure to the war in Laos, needless to say, when he heard the news that Laos had fallen, he told the Hmong Daily News, “I was disappointed but not surprised. At least the war came to an end although it led to the flow of refugees out of Laos to escape from the emerging Communist regime.”

“Did IVS make any significant contributions in the long-term development of Laos?” asked James Malia. “It is hard to say. Our primary contribution was at the human level. We worked to impart knowledge, skills, and awareness of alternatives. How many of those we assisted were still alive at the end of the war, how many chose to stay in Laos, and how many were able to work with the new government, is unknown. Hopefully, there were some. IVS did what it could.”

During the years following the closure of IVS’s operations in Laos in 1975 a number of former volunteers returned to Laos and traveled throughout the country to visit cities and villages where they used to work. Almost invariably their experiences were positive, meeting people they used to know and seeing the outcomes of projects they initiated. There were also a few IVS volunteers who returned to Laos in different capacities to support development programs. One of the former IVS education volunteers, Wendy J. Chamberlain, returned to Laos as the US Ambassador from 1996-1999.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment