PART ONE:

The “Double Nickel” — Special Forces in El Salvador

By Greg Walker (ret), USA Special Forces

SF soldiers assigned or attached to the U.S. MilGrp -El Salvador were awarded the JMUA early on in the campaign.

“Operating under the potential and real dangers of both political and physical fire, U.S. Armed Forces personnel designed and carried out a program to help build the Salvadoran Armed Forces from a small, ill-equipped and poorly led force to the point where it is now well on the road to becoming one of the finest fighting forces in Latin America.”

~ Mr. David Passage, charge d’ affaires, U.S. Embassy San Salvador, Memorandum to U.S. Southern Command CinC

Passage, whose duty station was the embassy in San Salvador, goes on to point out that U.S. Military Group (MilGrp) personnel “have been shot at” and “that they are high priority targets for enemy attacks.” According to the memorandum, then-ambassador Thomas Pickering “specifically requested to be associated” with the recommendation that a Joint Meritorious Unit Award (JMUA) be authorized to those members of the MilGrp assigned and attached and who served for over sixty days in any capacity between January 1, 1981, and June 7, 1985. “The Military Group has been paid the ultimate compliment,” wrote Passage. “The Communist-backed guerrillas have publicly ascribed to them the fact that the guerrillas are losing their war. No commendation can be written that is so credible a testament to their effectiveness.”

The “Double Nickel”

“Congress and the administration had agreed to this limit with little discussion or rancor. This was something like a handshake deal. When some members attempted to write it into law, they failed. This seems like the way policy and politics ought to work. Honorable individuals of two branches of government and two parties decide what the issue is — we want to avoid creeping from training and advice to full-scale involvement à la Vietnam. How do you do it? You keep the numbers too small to get into real trouble. What size is that? The 55-man limit, in which so many put so much stock (and many thought was the law of the land) was arbitrary and had been reached in offhand fashion.” (El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means by Donald R. Hamilton, 2015)

In 1981, fifteen Green Berets were deployed to El Salvador. They were selected for their linguistic abilities and training expertise. The composite team under the command of then Captain David Morris was stationed in the Republic of Panama with the then forward deployed 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) at Fort Gulick. Their mission? Train the struggling Salvadoran Army’s first immediate reaction battalion, the Atlacatl, at Sitio del Nino just twenty miles from San Salvador.

However, this was not the first time U.S. Special Forces had interfaced with the Salvadoran military. American advisers began working alongside Salvadoran military units in 1962 when the first mobile training team (MTT) was deployed to conduct a counterinsurgency/civic action/psychological operations survey. On June 30, 1972, the 8th Special Forces Group, preceding the 3/7th in Panama, was deactivated. It then became the 3/7th which would carry out the bulk of upcoming MTTs to El Salvador, specifically from January 1, 1981, until the United Nations brokered Peace Accord in February 1992.

Dr. Todd Greentree was a junior political officer with the U.S. Department stationed at the embassy in San Salvador during this period. In May 2021, Greentree shared his assessment of the political/military situation in El Salvador during his tenure there. “Saigon had fallen just a few years earlier,” he points out. “But after Nicaragua, the U.S. was not going to lose another country to the Soviet Union and Cuba in Central America. President [Jimmy] Carter found aiding the Salvadoran government extremely distasteful, and his ambassador, Robert White, was an emotional human rights crusader, especially after the four churchwomen were raped and murdered [by Salvadoran troops] on his watch.

“Yet it was Carter who authorized lethal assistance to the Salvadoran military in one of his last decisions before leaving office in January 1981. Reagan inherited El Salvador as [his] first foreign policy crisis. He eventually embraced counter-insurgency but was initially more concerned to reassure Americans that El Salvador was not going to become another Vietnam.”

Forced to appease public opinion at home, the Pentagon devised a plan to establish a limit on Special Forces advisers to serve in El Salvador. As fifty-five advisers were already stationed and working in El Salvador the decision was made to preserve the funding already in place. The Pentagon told both the President and Congress, when asked, that fifty-five in-country advisers/trainers was a satisfactory number. After that the manpower ceiling was “etched in stone,” according to a former MILGRP commander. In 1979, funding for the growing civil war in El Salvador stood at $12 million dollars. By 1982, this amount had increased to $80 million. Mission requirements (i.e., a military victory over the communist insurgents) increased, as well. The guerrilla forces fighting under the banner of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) were proving to be far more organized, better funded, and trained by Cuban, Nicaraguan, North Vietnamese, and East German advisers than originally anticipated. “No one wanted to take the chance of seeing the increased aid cancelled,” offers a former MILGRP member. “It was obvious more advisers were required to carry out the additional taskings, yet the limit of fifty-five would not be challenged.” It was believed that requesting additional advisers would invite disaster. Political and social push-back was growing in the United States, fueled by the negativity of the Vietnam war still fresh in the minds of many Americans and the 5th Column of Marxist organizations and social activists groups in the United States.

The peace movement ramped back up to mount protests against U.S. aid to El Salvador

“The War Powers Act and the Reagan administration’s careful avoidance of its triggers guided military action in El Salvador in two critical ways. First, it created the 55-man limit on the size of the MILGRP. Although this limit never had the force of law, it became an informal but honored deal between the administration and Congress: Keep it at 55 and we the leadership will not seek a confrontation over the War Powers Act. The second was the administration’s pledge to Congress that U.S. military personnel “will not act as combat advisors, and will not accompany Salvadoran forces in combat, on operational patrols, or in any other situation where combat is likely.” This second pledge defined the operational boundaries for U.S. personnel.” (El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means Donald R. Hamilton, 2015)

The “Double Nickle,” as the Green Berets serving in El Salvador self-described themselves, became a tripwire limit for the Congress to demand adherence to. Fortunately, there was a way around the “55” and the Pentagon used it almost immediately.

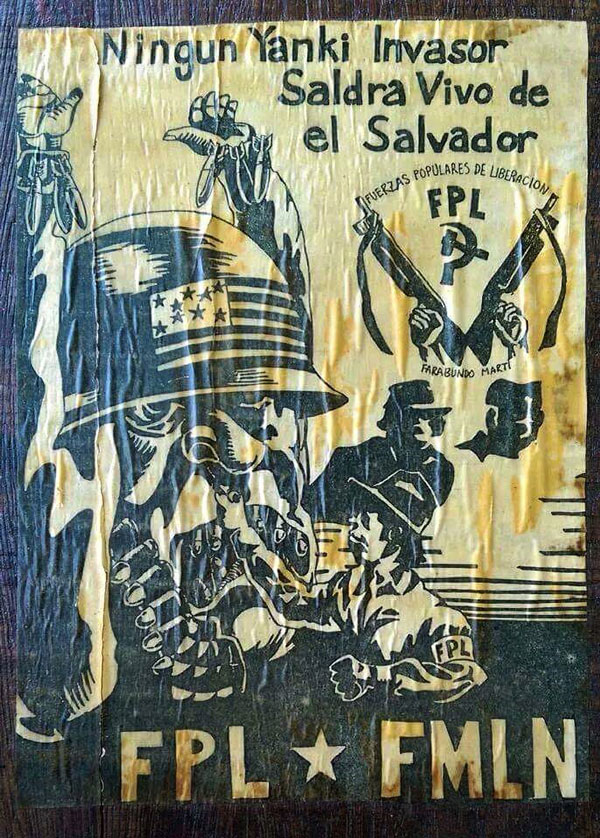

“No American invader will leave El Salvador alive”. Leaflets like these were commonplace during the war and American Special Forces advisers were at the top of the guerrilla hit list.” (Author collection)

“Don’t get caught”

Policy loopholes existed which allowed for additional Special Forces qualified soldiers to be assigned legally in-country. The positions allotted to the MILGRP were filled with Green Berets who would not be counted under the “55” line in the sand. In this manner, the number of uniformed advisers/trainers assisting the Salvadoran military was between 85 and 100 “snake eaters” at any one time. The advisers were complimented with an additional 50 to 75 CIA paramilitary advisers/trainers, many of these Vietnam veterans of the MACV-SOG special projects during the Vietnam war, a fair number who had remained in Special Forces reserve units after leaving active duty.

And Congress did its part on both sides of the aisle. “The six-man permanent party in the MILGRP was insufficient to support all the movement of all the supplies and MTTs flowing into the country. Congress was notified, did not object, and the staff was increased to twelve. After about 18 months, it became obvious that Salvadoran soldiers injured on the battlefield were dying or becoming permanently disabled because Salvadoran battlefield medics were insufficient in numbers and deficient in training. The U.S. had the capacity to train them but did not have a means to do so within the 55-man limit. Eventually Congress informally agreed to exclude members of a medical MTT from the count.” (El Salvador in the 1980s: War by Other Means, Donald R. Hamilton, 2015)

Special Forces advisers received imminent danger, or combat pay, the appropriate documentation provided by the MILGRP commander stating the adviser had been/was exposed to hostile fire.

In a 1986, Army legal decision regarding the increasing submission for combat awards and decorations for those who were either taken under enemy fire or in the field with their Salvadoran units conducting operations, the JAG advised the Pentagon there was no legal reason such awards should not be authorized. The Army, in specific, was quick to ignore the decision for purely political reasons, whereas the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force continued to approve such awards and decorations for their service members in El Salvador.

“We were in a war. Everyone knew it was a war,” recalls one Army adviser/trainer. For the Green Berets in specific the unwritten warning was not to get caught by the international media in the field or carrying anything more than a handgun.

“You could expect to be put on the First Thing Smok’in back to Panama if you were photographed or filmed with an M16 rifle,” recalls a retired El Sal veteran. “We were authorized to draw and carry M16s, MP5 submachine guns, grenades, and shotguns once on the ground. Sometimes we drew the weapons from the Salvadoran units we were working with. Other times we drew them from the embassy armory. It was a cat-and-mouse game with a mild reprimand if you got caught.”

And from a former embassy public affairs officer. “Most of the international media stationed in El Salvador understood that our guys carried something other than a pistol. I (and many others) told journalists and anyone else who would listen that the policy and congressional understanding was that the trainers were forbidden to be “equipped for combat” and that a long gun did not meet that standard. I think politicos in Washington panicked and demanded the guys [be] sent home after being photographed with M-16. Most of the serious journalists understood that the guys sent home were not guilty of anything substantive.”

In the meantime, Purple Hearts were already being approved, albeit very quietly, for 3/7th Green Berets wounded in-country like SSG Jay Stanley in February 1983 while traveling by helicopter in what was described as an “operational flight”. Stanley was returned to Panama to recover from his wound. He received a Purple Heart. Two warrant officers and a master sergeant were deemed responsible for his being on the flight and were put on “the next thing smok’in” back to their unit at Fort Gulick.

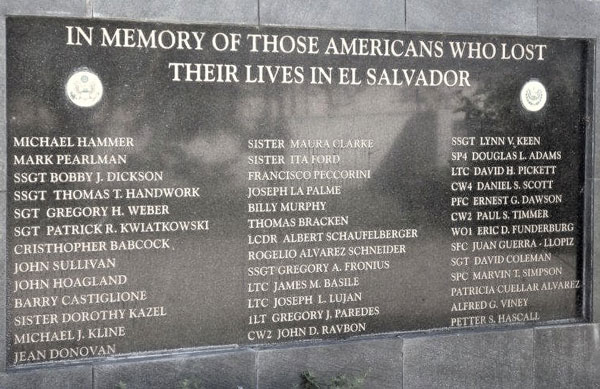

A stark reminder at the U.S. embassy of those Americans killed during El Salvador’s civil war. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

Killed in action – stories behind the body count

Thirty-nine Americans were killed over the course of the ten-year civil war in El Salvador. In the case of those who were U.S. service members, how they died was all too often misrepresented by the U.S. Government at the time or outright lied about.

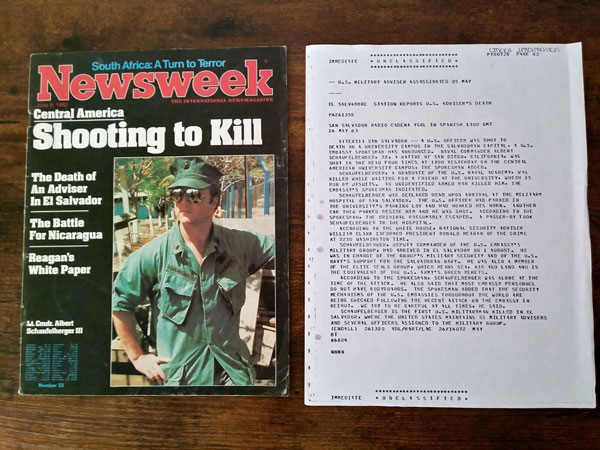

May 25, 1983 — LCDR Al Schaufelberger, 33, of Chula Vista, California, deputy commander of the U.S. military advisory group in El Salvador and the embassy’s senior security officer was the first American service member killed in El Salvador. He was shot in the head three times as he sat in his car on the campus of the University of Central America in San Salvador, waiting for his girlfriend. A Marxist guerrilla group claimed it conducted the assassination. An FBI investigation conducted in-country offered the Navy SEAL officer had been killed by a jealous former boyfriend of the young woman. However, in a 1993 interview, former guerrilla commander Gilberto Osorio affirmed the attack was conducted by a small urban terrorist cell seeking to become the sixth fighting force under the FMLN umbrella. The FMLN had rejected the group’s request and in turn its members sought to demonstrate their effectiveness. The fierce political blowback from Schaufelberger’s murder forced the FMLN to disown the killers.

The author visited with LCDR Schaufelberger the day before he was assassinated. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

June 19, 1985 — the Zona Rosa attack — four marines were the first American military personnel to be killed since May 1983, when Lieut. Comdr. Albert A. Schaufelberger was shot to death as he sat in his car on the grounds of the Central American University.

The slain marines were members of the guard force for the United States Embassy. They were wearing civilian clothes and per embassy policy were unarmed while off-duty. Two other marines survived the attack without injury.

Four U.S. Military–Marine Security Guards were killed in the Zona Rosa attack in San Salvador, El Salvador on June 19, 1985. A warning was received at the U.S. embassy about an impending attack, but the Marines were never informed nor prevented from off-duty activities in the city. Embassy guards were not permitted to carry sidearms unless on duty. (Photos U.S. Marine Corps)

Staff Sgt Bobby Joe Dickson

Staff Sgt Thomas Handwork

Sgt Patrick R. Kwiatkowski

Sgt Gregory H. Weber

Two individuals allegedly connected to the Zona Rosa operation, Pedro Andrade and Gilberto Osorio, were living in the United States. At the time of Andrade’s arrest in El Salvador in 1989, he was alleged to have masterminded the attacks. In June 1990, he was allowed to enter the United States on a three-year public interest parole. Osorio is a United States citizen and is still living in San Francisco, California. After a May 1995 CBS 60 Minutes expose, hosted by Ed Bradley, the U.S. Department of Justice investigated both Osorio and Andrade. Andrade, identified as the mastermind for the operation, was found to have become an informant for the CIA ,which later allowed him and his family to relocate to the United States. Upon this discovery, Andrade was deported back to El Salvador.

Osorio, who fought under the name “Gerardo Zelaya,” is a former guerrilla commander whose last command was with the FMLN–PRTC, the most violent army of the five such forces under the FMLN flag. It was the PRTC that sanctioned the attack on the marines. According to the U.S. DOJ report, “Osorio was one of the founding members of the CPS, which was formed in November 1979 to support the Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR), a Marxist terrorist group composed of students, peasants, and labor unions whose objective was to establish a Marxist government in El Salvador. The source also reported that Osorio had worked on “El Pulgarcito,” a Salvadoran newspaper. The source reported that Osorio and Martinez were going to travel to Mexico City, where they would meet with Rafael Manjivar, a member of the Communist Party of El Salvador. They would then travel to El Salvador to establish direct contact with the guerrilla groups and join them in the struggle in any capacity that the Coordinadora [Leadership Coalition of Leftist Groups in El Salvador] wanted. The source advised that Osorio wanted to join the fighting groups or terrorists.”

Osorio was found not to have participated in the actual attack but in his role as Chief of Operations for the PRTC he, as likely as not, knew of the plan.

A warning was received at the U.S. embassy about an impending attack, but the Marines were never informed nor prevented from off-duty activities in the city. Embassy guards were not permitted to carry sidearms unless on duty.

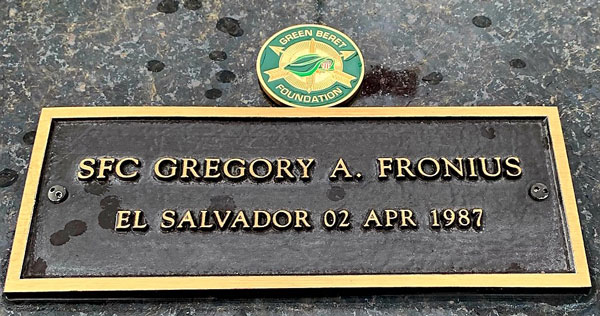

Today the language lab at 7th Group is named after the 1st Green Beret KIA in El Salvador. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

March 31, 1987 — Relatives of SSG Gregory A. Fronius, a 28-year-old Green Beret sergeant, were told he was slain during a guerrilla attack on the Salvadoran brigade’s headquarters at El Paraiso. They were informed Fronius had died in his barracks while asleep when a mortar shell struck. In fact, Fronius had bolted from the barracks to rally Salvadoran soldiers for a counterattack. Fronius, fighting alone from an elevated position, bought time for Salvadoran officers to secure the command bunker when several guerrilla sappers (trained by the North Vietnamese in Nicaragua) shot him multiple times. Fronius, slipping down a stairwell into the courtyard below, was mortally wounded, as his autopsy report was obtained years later in a FOIA request of the Army showed. Upon reaching his body the guerrillas realized he was still breathing. Enraged to find an American adviser had thwarted their plans to attack the bunker, they placed a shape charge beneath his body and detonated it.

Upon returning from San Salvador, his team leader, Major Gus Taylor, helped collect the young Green Beret’s remains. “We recovered about 17 pounds of Greg,” he told this author over the course of several interviews. The rest was scattered…we had to pick pieces of him out of the overhead trees.”

Taylor and another member of his mobile training team would set out with selected Salvadoran snipers from the base after he had met with the then U.S. MILGRP commander. For 30 days the men hunted down and shot any guerrilla or guerrillas they encountered. Taylor, deeply affected by the loss of Fronius, would later provide crucial photographs and information to the Veterans of Special Operations – El Salvador while they were being interviewed by CBS’s Ed Bradley in 1995. Greg’s brother, Stephen, was also interviewed. He also met privately with Taylor.

In June 1998, at the largest awards and decorations ceremony held by the 7th Special Forces Group (A) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, SFC Fronius’ 12-year-old son stepped forward to receive his father’s posthumous — and initially denied by the Army — Silver Star.

May 1996 — while attending the dedication of a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery honoring those KIA in El Salvador, Ms. Judy Lujan, wife of Army Lt. Col. Joseph H. Lujan, recalled the Army telling her that her husband died in [July] 1987 when the helicopter carrying him crashed into a hillside during stormy weather. (View the Memorial ceremony at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3uy8Ey23Is&t=36s)

“But the Army never produced her husband’s personal effects or photographs of his corpse, despite her repeated requests,” she said yesterday. “I can’t get on with my life, I can’t do anything, until I know for sure he’s dead,” she stated. (Public Honors for Secret Combat, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1996/05/06/public-honors-for-secret-combat/f764f45e-1b75-4e8c-8c32-94844434d5e0/)

After the crash, the Army had announced the bodies of those killed had been recovered and returned to Panama. It was a lie.

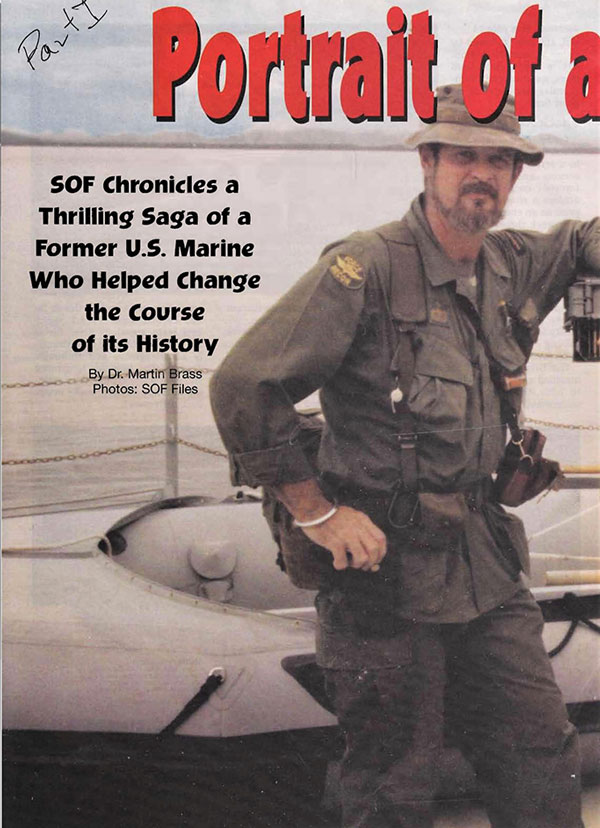

Marine Force Recon veteran Harry Claflin trained and advised the Salvadoran parachute battalion, and later created and trained the Special Operations Group (GOE). Commissioned as an officer he would spend nine years in El Salvador as a combat adviser and mentor. (Robert K Brown/Soldier of Fortune, Sept. 2007, https://www.sofmag.com/sof-fights-communism-in-el-salvador/)

Harry Claflin is a Force Recon veteran of the Vietnam war. He spent nine years in El Salvador as a trainer and combat adviser and was commissioned as a captain by the Salvadoran Army. His capabilities, accomplishments, and professionalism were officially recognized by both the Salvadoran Armed Forces and the U.S. MilGrp as well as the United States Marine Corps. He is an Associate Member in Good Standing of the Special Forces Association.

“None of the bodies were recovered,” recalled Claflin in early 2021. “The lake is over nine hundred feet deep. I was there at the [Air Force] base when the crash happened. It was really foggy, and the pilot misjudged the height of the bank and hit hard. I was in my BOQ, and it woke me up. I got with [Mike] Kim who had been teaching SCUBA to a team from the PRAL recon company. He said where it went into the lake was the deepest part.

Marine Force Recon veteran Harry Claflin trained and advised the Salvadoran parachute battalion, and later created and trained the Special Operations Group (GOE). Commissioned as an officer, he would spend nine years in El Salvador as a combat adviser and mentor.

“The lake gets warm from time to time. I did not know it was still an active volcano. The last time it had any active action was in 1986 when we had the earthquake in San Salvador. If it blows it will take Illopango city and the air base off the face of the earth.

“That is the reason all the military aircraft were moved to Cumalopa, and a new base built. The only thing left at the old base is about two hundred paratroopers and base maintenance. The runway and part of the old base is a civilian airport now.”

The nighttime mission Colonel Lujan and the others were killed was a medevac effort. Two Special Forces advisers, assigned as trainers at the Salvadoran training base in La Union, had gotten into an argument over a Salvadoran female. During the confrontation, one of the Green Berets shot the other with his M16. Due to the seriousness of the incident senior American military officers were onboard the helicopter as investigators.

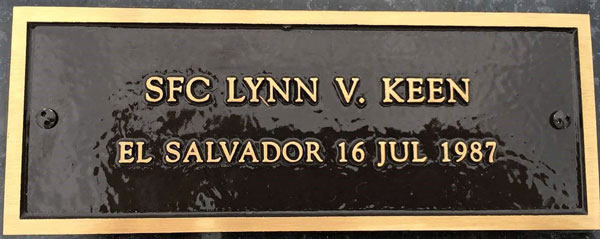

SFC Lynn Keen, MOS 1840D, was assigned to A-Co, 3/7th SFGA at the time of his death. (Photo courtesy Greg Walker)

Just seven minutes after taking off the pilot was forced to attempt to return to the airfield due to extremely poor weather. It was during this attempt that the crash occurred. The Pentagon identified the victims as: Sgt. 1st Class Lynn Keen, 27, a Special Forces medic; 1st Lt. Gregory J. Paredes, 24, a pilot; Chief Warrant Officer, John D. Raybon, 29, copilot; Spec. 4 Douglas L. Adams, 22, of Corvallis, Ore., the crew chief; and Lt. Col. Joseph L. Lujan, 41, Special Forces. Also killed was Air Force Lt. Col. James M. Basile, 43, of Cheshire, Conn., the deputy commander of the U.S. Military Group attached to the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador.

The only survivor was identified as Sgt. 1st Class Thomas G. Grace. An official said Sgt. Thomas G. Grace, 32, an Air Force medic, was seriously injured in the crash. Salvadoran civilians found Grace and called for help. A Salvadoran helicopter crew had also launched at the same time but took a different flight route due to the weather conditions. It successfully reached La Union and transported the wounded Special Forces solder to San Salvador. The Green Beret, who was evacuated by the Salvadoran helicopter, underwent surgery at a San Salvador hospital for a severed artery in the neck, a Pentagon spokeswoman reported. He was reported in stable condition and later flown to an Army medical center in Texas.

Although consideration was given by the Pentagon to recover the bodies from the lake, it was determined the effort would have required hardhat divers and would have been a major undertaking during an ongoing shooting war. An inquiry by this author as to the status of the missing service members and any thought of mounting a recovery operation today was submitted to the Defense MIA/POW Accounting Agency in Hawaii. At the time of publication there has been no response.

The hard right over the easy wrong

In the case of U.S. special operations forces and how they affected the longest war in Central America, their performance and credibility clearly outshone that of both military leaders and politicians back home. In March 1993, to his great credit, former USA Special Operation Command commander GEN Carl W. Stiner (ret.) sent the author a formal letter in support of combat awards and decorations. “I concur with your proposal,” the highly respected Special Forces officer wrote. “Without the superb support of the special operations forces in El Salvador, the duration and intensity would have been even greater.”

Click here to continue to Part Two:

About the Author:

Greg Walker (ret) served with the 10th, 7th, USASFC, and 19th Special Forces Groups (Airborne). He is a veteran of the war in El Salvador and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Mr. Walker founded the Veterans of Special Operations – El Salvador, a grassroots fraternal organization that was at “the tip of the spear” in the 10-year long political campaign to see combat awards and decorations authorized for those who served, all Services, during El Salvador’s civil war. He is a Life member of the Special Operations Association and Special Forces Association.

His awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge (X2), the Special Forces Tab, the Meritorious Service Medal (X3), and the Washington National Guard Legion of Merit.

A DoD trained and certified Warrior Care case manager with the U.S. SOCOM Warrior Care program (2009-2013) Walker advocated for the most seriously wounded, injured, or made ill Special Operations Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, and Airmen serving during the Global War on Terrorism.

He is the author of At the Hurricane’s Eye — U.S. Special Operations Forces from Vietnam to Desert Storm (Ivy Books, 1994), among other literary contributions to U.S. SOF history.

Today, Greg lives and writes from his home in Sisters, Oregon, along with his service pup, Tommy.

Photo: Greg and Tommy

Aloha, Greg, it would be my honor to have you attend this humble NCOs retirement ceremony in June/July 2023 in Hawaii. I hope you remember me from our CFLCC pre-OIF knife/close-hand combat training days on Doha ~ Claudia (SGM, one each)

Greg, I am/ was a personal friend of CW2 John Raybon( misspelled on the marble memorial at the embassy in San Salvador) and attended his funeral here at Ft. Bragg( it will ALWAYS be Ft. Bragg to me). Is he MIA? Did we not bury my friend? Is he still at the bottom of that lake/ volcano? Did SFC Thomas G. Grace swim ashore.?We were told the aircraft crashed into the side of the volcano as the shifting weather pushed the aircraft (a UH-1H) closer to that side without knowing it.

Greg, I need to know, is he buried here at Ft. Bragg or what can I do to mount an investigation or whatever it takes to get these heroes ( including a still grieving wife’s husband) recovered and buried in a country they died for, not died in?

Sincerely,

Bret Andres

US ARMY( ret too)

Hi Bret, your comment has been passed on to Greg Walker. Coincidently Greg has been working to track down information about the incident you refer to. If you haven’t already heard from him, I’m sure you will soon.

Regards, Debra Holm, SFA Chapter 78 Webmaster

I knew Chief Raybon, and Doc Keene from Spec Ops on the ES/Hondo border the summer of ’84. There have been posts about this on the Facebook group- US Army Honduras and Panama. A replier said he was on the causality recovery mission..

The US GOV policy during the war in El Salvador was to present the deaths and wounding of US military personnel in El Salvador as anything other than combat related. Literally every US service member killed during that war was subject to an alternate truth regarding their deaths. In May 1996, Ms. Judy Lujan, while attending the dedication of our memorial at Arlington National Cemetery gave this quote to the Washington Post.

“Judy Lujan, wife of Army Lt. Col. Joseph H. Lujan, was told her husband died in 1987 when the helicopter carrying him crashed into a hillside during stormy weather. But the Army never produced her husband’s personal effects or photographs of his corpse, despite her repeated requests, she said yesterday. “I can’t get on with my life, I can’t do anything, until I know for sure he’s dead,” she stated.”

I have spoken to Ms. Lujan and others recently and our conversations have led to a number of FOIAs being submitted to various US GOV agencies regarding this tragic crash.

There are significant events and questions regarding the US GOV claim of having recovered all those who were killed in the crash…as Ms. Lujan’s 1996 statement reveals.

I am hopeful that as with the case of SFC Greg Fronius (KIA 1987), and LTC David Picket and his crew chief, shot down in 1991. In all three cases the US GOV first claimed there was no combat involved in the deaths. In 1998, after investigations were pursued, it was shown all three had died as the direct result of a military action. Fronius’ family would receive his revised decoration, originally denied, of the Silver Star. Pickett’s family, after a long battle, would receive his posthumous POW medal.

Because of the charade surrounding her husband’s death – Ms. Lujan only this year began receiving her husband’s full survivor benefits pay (55% of his retirement pay). Up until this year she only saw $200 a month remitted – due to the apparently misleading official account of LTC Joseph Lujan’s death.

In SF, and SOF, our credo is “No Fallen Comrade Left Behind”. More to follow as this investigative report unfolds.

I had been in El Salvador for exactly one month when this helicopter accident took place, a couple of days after the accident i saw pictures taken by CW2 Jose A Salazar (RIP) a H500 PILOT of all military personnel who died when the Huey crashed against the mountain as they took off from Ilopango. That picture is still fresh in my mind.

I was in San Salvador the night of the accident serving with a Medical Training Team as an adviser in the Laboratory Field. Being assigned to the Department of Pathology due to my MOS it was my responsibility to take care of the bodies once they were recovered. I can attest to the fact that the bodies were recovered and I personally dealt with the situation.

Response sent directly to Greg Walker:

Thank you for the prompt response. The night of the accident I was at the Medical Team house with another team member (SSG Alberto Garcia ) and of course monitoring our Motorola radios. Garcia told me and I quote, ” We just lost a bird”, since he was paying close attention to the communications going back and forth. We immediately left the house enroute to the Military Hospital since it was our place of duty. We spent the night waiting for news and the recovery efforts. It took all night for the bodies to be brought back to the morgue. it was at that time that I recognized LTC Lujan, he had been to Fort Bragg (JFK antiterrorism training) with me prior to departing to El Salvador.

There was another Laboratory Technician with me as part of our team (SSG Juan Garcia) and it became our responsibility to body bagged all six bodies in preparation for sending them to Panama for further investigation (autopsies?). With the exception of one of the pilots who had a compound fracture on a leg, everyone else suffered the expected trauma due to the impact. Everything they had in their possession was left inside the individual body bags. Once the bodies were picked up from the morgue SSG Garcia and I had no other communication with the Mil Group Chain of Command or anybody else.

SSG Garcia retired in San Antonio, TX as a MSG, so did I.

Please let me know if you need any additional information.

Greg, it has been a long time since our 3/7 SFGA days at Fort Gulick when I was the Bn S-4 and the Support Center Director in the FOB when activated (5/78 to 5/80). Those days were confusing when were assigned to the Army Brigade in Panama meaning we were treated like a conventional Infantry Battalion (leading to many issues that needed resolution). But the real comment I was going was the late Joe Lujan was my class leader when we were in SFOC together (I was number two by seniority in the class with special instructions due to my unique experience. I won’t bore you with how a conventional airborne QM Captain just completing a tour as the Commander of a composite Rigger unit in the 101st Airborne Division; another story/issue. The bottom line was I was an SF-qualified QM officer and it didn’t long to realize that I would not get another position in Panama. When I realized my Joe Lujan connection, I provided this story through social media to a member involved with the effort to help with the late LTC Lujan case. he was mentioned in your article. To make a long story even longer, I was not aware of Joe’s death until long after my retirement.

I end this diatribe with my apology/. This comes from a homebound guy with a lot of illnesses (ask Skip;)

Greg good morning. I am retired SGM Sanchez. I never had the honor of meeting you. I met a few others during the Civil War in El Salvador. I was one of those serving under ?. I trained and developed civilians and military on Psyops in country, I also served alone under two agencies out of the DNI umbrella made of U.S. and Salvadoran intelligence. Well just saying hello and remembering good and bad and risky moments in Country. Merry Christmas.

SGM Sanchez

Greetings from Texas! My classmate in the eighties father lived in El Salvador part time. He was a pilot in the army and was retired. He brought us t shirts from his bar which was located in El Salvador. I was young and spent many hours by late night camp fires listening to his stories of duty, honor and hell. He passed many years ago. I cannot locate any information on his army service time in Vietnam which he had many awards and medals from. ….. or contractor work he eluded to many times. Fast forward. 40 years passes. I retire from my own 30 year career working for USG and government contractors. Last night he came to me in a dream and demanded I find out who he was during those years in El Salvador. I realize this is totally out of left field. He made an enormous impact on the path I followed as a young man. Any information you might be willing to share concerning Mr. John kellum would greatly be appreciated. No pressure as this request seems ridiculous.