Pat Sajak —

A Belated Merry Christmas from Richard M. Nixon!

ABC-TV's Wheel of Fortune game show host with fellow troops at American Forces Vietnam Network. Sajak is third from the right in the back row. (Photo courtesy Pat Sajak)

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

From the forthcoming book Hot Mics and TV Lights: The True Story of the American Forces Vietnam Network by Marc Phillip Yablonka with Rick Fredericksen.

I first spoke with Pat Sajak in the spring of 2004, having had the good fortune to interview him for an article I was then writing for American Veteran magazine, the quarterly publication of the AMVETS organization, on the history of the Armed Forces Network. Around that time, there was a contestant on the ABC-TV game show Wheel of Fortune, for which Pat was and still is the MC, who had won a lot of money. Pat, being happy for him, responded in kind with a hug. Not long after that, the contestant sued Pat for bodily injury!

On the day of our appointed interview, the phone rings and it’s Pat on the other end of the line. He says, “Let’s see, Marc. What are we supposed to be talking about?” I answered, “Don’t worry Pat! I’m not gonna sue you!” Pat cracked up and what was supposed to be 15 minutes that Pat’s management had allotted out of his valuable time turned into at least 45 unforgettable minutes for me, that resulted in the following story for Vietnam magazine.

When ABC-TV’s Wheel of Fortune game show host Pat Sajak joined the U.S. Army back in 1968, he was looking for “that golden experience in broadcasting,” having previously gotten his first break in radio on WLS in his native Chicago, where he was asked to be a guest teen disc jockey on the Dick Biondi show. It turned out, however, that the Army had other plans for the Windy City deejay.

Astute as the Army might have been with a broadcaster, it did what Sajak called the “obvious”: it trained him to be a clerk typist, shipped him off to Vietnam and made him a finance clerk on the base at Long Binh, about 30 miles outside Saigon.

“And I was a good one too,” Sajak insisted. “I took the job seriously. When I got there, the papers were an absolute mess and I straightened them out. Soldiers would come back just to thank me.”

Sajak was such a good clerk typist that his request to transfer to AFVN, where there was an opening for a morning man, was turned down four times.

He finally wrote a letter to his Congressman, Roman Pucinski (D-Ill.), who coincidentally owned WEDC, the first radio station to hire Sajak (as a newsman). WEDC was a 250-watt multi-lingual station on which Pucinski’s mother had a Polish language show. The Congressman wrote a letter in Sajak’s behalf.

“It’s amazing the power that politicians have,” Sajak said.

Sajak’s own paperwork came through this time and soon he was one in a line of AFVN morning men playing Top 40 tunes, leaning into the mic and speaking those three memorable words most often affiliated with Robin Williams: “Goood morning, Vietnam!”

When asked about that, Sajak said that waking the country up (on the Dawnbuster Show) with those words was very much like what happened with perky radio jingles in those days. Like the jingles, Good Morning, Vietnam just went with the morning drive show. In fact, Sajak recalled a time in the beginning of his career when, because stations were always trying to cut financial corners, morning jocks had to take the name of the deejay that had preceded them in that time slot since those names were already on the pre-recorded jingles.

Sajak remained in Vietnam until New Year’s Eve 1970, having extended his tour another six months because, he is a little reticent to say, he enjoyed Vietnam. “I mean who wouldn’t? There I was living in a hotel, eating in restaurants every night.”

He is quick to attempt to put his Vietnam service into personal perspective though. He notes that others’ lives hung far more in the balance day after day than his ever did.

But serving in Saigon was not always a cake walk.

Sajak recalled how, owing to the infamous 1968 Tet Offensive, which brought the war into the streets of Saigon, indeed to the U.S. Embassy itself one year later, during Tet `69, all rear echelon personnel were ordered to wear a sidearm and practice the use of it at the firing range.

When Sajak went to the range, he found his weapon wouldn’t discharge because the firing pin was broken. Unaccustomed to carrying a gun (“I was not adept at them. Prior to that, I had never carried a weapon in Vietnam”). He was ordered to replace his firing pin. He never did. “I would have been more dangerous to my roommate than any Viet Cong walking the streets of Saigon,” he recalled with a laugh.

It is fair to say that the threat of danger was always there to one degree or another for everyone in Vietnam. During the Tet Offensive in 1968, AFVN’s entire network was put under alert. The Army Headquarters Area Command advised the Saigon station it might be targeted. Extra security was posted and broadcasters were advised to have their weapons accessible. In fact, an alert had gone out to all AFVN detachments in the country, warning that “our facilities may be a target of enemy attack,” and should be prepared to go off the air.

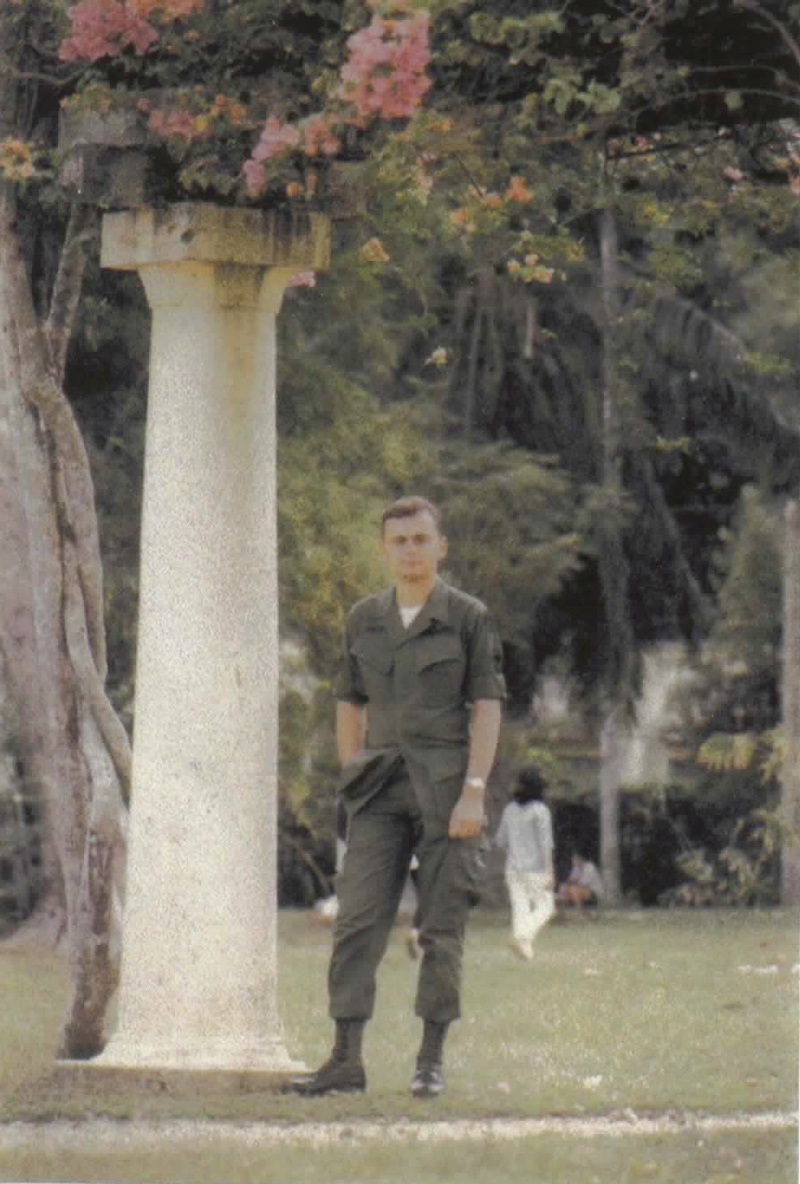

ABC-TV’s Wheel of Fortune game show host Pat Sajak (né Sajdak) in Vietnam. (Photo courtesy Pat Sajak)

Despite the constant threat of danger, Sajak felt almost inexplicably safe during his tour as the AFVN morning man in Saigon. “It was funny and strange. There was a war going on. Barbed wire was everywhere and I was playing records and going to restaurants every night. It was a fairly normal life. And given the circumstances, mine was a pretty lucky duty.”

For Sajak, deejaying for AFVN was also the best radio gig he ever had. He had told me it was the largest radio station he ever worked for and his audience was the largest he ever reached because it could be heard by most American GIs and civilian personnel in-country. His program was simulcast from 6:00 A.M. to 9:00 across AFVN’s up-country affiliates, so the reception was available to a vast portion of South Vietnam. The potential shadow audience of Vietnamese civilians was enormous.

“The philosophy of the station was to program it like a stateside radio station. We played Top 40 music since the listeners were mostly young men. We didn’t have commercials, but we did have snappy PSAs (public service announcements): `Be sure to keep your M-16 cleaned.’ That kind of stuff. We produced our own jingles and ran tight shows,” he said.

Despite AFVN also having television coverage in Vietnam, it was limited by the technology of the day. Because of that, he didn’t get to see Neil Armstrong walk on the moon until the following day because it was on tape delay. It’s one of the anomalies of the Vietnam War; U.S. personnel in Vietnam were among the few Americans in the world who were unable to watch the historic Apollo 11 moon landing on live TV.

Being the AFVN morning man, Sajak was often flown from base to base to warm up the crowds at USO shows where he would introduce stars the likes of Bob Hope.

“Ironically, I never got to meet him. They would just fly me from this auditorium to that one. For security reasons, they would never tell me where I was going. I would be Hope’s warm-up act. But it was a thankless job. The guys didn’t come to see me. They came to see Connie Stevens and Hope. I’d introduce them and be whisked back to Saigon.”

Notwithstanding the fact that Hope and Sajak never met, that does not mean that Sajak’s time on the air at AFVN was devoid of humor. In recent years, one such occurrence was relayed to his fellow AFVN disc jockey, Rick Bednar, who recounted the story in the latter’s interview in Radio World magazine.

“Pat recently told me about a humorous experience he had while hosting his AFVN morning show. President Nixon was scheduled to deliver a Christmas television address to the nation in 1969, and, due to the time difference (and the fact that satellite technology was in its infancy), we were carrying it only on radio during my morning show,’” Bednar recalled Sajak telling him.

“I was playing music as usual, but monitoring the CBS network in one ear. When I heard the president being introduced, I broke in to my music and said, ‘And now the President of the United States.’ I flipped a switch, and the speech could be heard throughout Vietnam.

“Nixon came to a moving conclusion, and there was silence as he began shuffling his papers. I flipped the switch again and resumed my show,” Sajak continued.

“A few seconds later, I was horrified to hear through that same ear that he had resumed speaking. Not only that, he was sending Christmas greetings directly to the troops in Vietnam, who were listening instead to the 1910 Fruitgum Company’s rendition of ‘1, 2, 3 Red Light.’”

“I could have admitted my mistake and gone back to the speech, but I figured there was no point in doing that because I was the only one in the world who knew that Richard Nixon was directing his comments to only one soldier: me! So, if you were in Vietnam at Christmastime in 1969, allow me to wish you a belated Merry Christmas from Richard M. Nixon!”

Humor aside, it is safe to say that Sajak also didn’t sleep very well from the day he worked his first shift at AFVN. There was a nightly curfew in Saigon which didn’t lift until 6:00 A.M., exactly the time he had to sign on the air. That meant, of course, that he had to sleep in the station.

Pat Sajak and Vanna White of "Wheel of Fortune" address the studio audience on Feb 8, 2006, during a taping of the popular game show. The show featured 15 service members as contestants when they hosted "Wheel Salutes the Armed Forces." (Photo credit: U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Tom Sloan)

Because of the nature of his MOS (Military Occupational Specialty), Sajak also got out to meet a lot of the people, both GIs and the local population. To this day, Sajak feels very taken by the Vietnamese people. While in-country, as happened to the Adrian Cronauer character in the Robin Williams film, he was hired to teach conversational English to eager Saigonese, from teens to elderly. That is, until the Army found out that he was drawing two paychecks courtesy of Uncle Sam. That rather abruptly ended Sajak’s fledgling career as an English instructor.

“I often wonder what happened to the people in my English class after what their country has gone through. They were all such nice people. I hope they survived. They deserve to live in a peaceful land.”

And while there is a side of Pat Sajak that knows his duty in Vietnam did not come with the danger of his fellow vets who humped in the jungles of Vietnam, there is also a side of Pat that feels no guilt over that. It is a side of him that brings great satisfaction: He made thousands of GIs’ tours a lot more bearable and a little more like home.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment