Storied “Spy Girl” Betty McIntosh Lit Up Morale Operations Branch

Elizabeth P. McIntosh, then Elizabeth McDonald, in uniform in WWII. (Courtesy U.S. Army)

By Marc Yablonka

Six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered dashing General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who had distinguished himself during the battles of World War I, to head up the Office of Strategic Services, the OSS, which soon enlisted 13,000 brave men and women from an almost eccentric variety of backgrounds. The OSS was the first clandestine unit to serve all branches of the military and was the precursor to the CIA.

Names like Allen Dulles, who would become the first head of the CIA, Walt Rostow, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., later aides to President John F. Kennedy, John Birch, after whom the ultra-conservative society was named, Monsignor Giovanni Battista, later Pope Paul the VI, Arthur Goldberg, who went on to become American Ambassador to the UN and a Supreme Court Justice, all found their way onto the OSS roster.

Even film director John Ford, actor Sterling Hayden, and TV chef Julia Child held membership in this elite intelligence community.

Yet another name on the list was Betty McIntosh.

Not long after her enlistment into the spy corps, she lay sleeping in Mei Yuan Women’s quarters of the OSS compound in Kunming, China. Without notice, a group of Chiang Kai-Shek’s Chinese nationalist troops burst through the door with an unassembled machine gun and ran to the balcony, where they began to fire on the Maoist forces who were strafing the city.

Strangely, that incident was not the most harrowing for the former Scripps-Howard News Agency war correspondent from Leesburg, Virginia. What she termed “a trip over the hump” was. That March 1945 journey—a flight in an ATC (Allergic to Combat, she laughingly calls it), zigzagging up, down, and over the steep mountains of southern China, while the planes seasoned pilots of the CBI (China-Burma-India) Theatre dodged lightning and thunder—was burnt upon her memory.

“You could look down and see other planes which hadn’t made it. They were like crosses in the snow,” she remembered sadly.

In her autobiography Undercover Girl, published in 1947, she recalls how, on that very same “milk run,” as the pilots called it, 26 ATCs were downed by Japanese Raiders in one ten-hour period on New Year’s Eve.

McIntosh thought she was destined for death and clutched many a talisman on the flight, including a St. Christopher, five-leaf clover, and a Japanese 1,000-stitch belt.

“The stitches represented prayers from as many Japanese girls for the return of the wearer,” she wrote.

She chuckled, recalling that, while most of the OSS operatives kissed Kunming’s tarmac when the plane touched down, her friend Julia Child, who had been reading a book, seeming completely undisturbed throughout the horrific flight, deplaned first and, noting the typical scenes one associated with China, “the coolies…the curling rooftop of a small temple near the airfield,” turned to disembarking compatriots and said, “Why this looks just like China!”

McIntosh, an operative from 1943 to 1945, was enticed into the service by a Department of Agriculture major, after being somewhat stymied in her journalism career.

“I wanted to go overseas and they were not letting the gal reporters go beyond Honolulu. I wanted to do in the Pacific what I hadn’t been able to do as a war correspondent. I was assured of a great time, though I didn’t have the foggiest idea of what I was getting into,” McIntosh said.

Her knowledge of the Japanese language, which she had picked up while living with a Nisei (second generation) Japanese family in Hawaii, put her in good stead to be assigned to the Black Propaganda Unit of Morale Operations (MO).

With black propaganda, contrary to white (“disinformation, the Office of Military Intelligence, the VOA [Voice of America] …”), “we practiced being double agents. We were thinking double, producing the dissemination of slanted propaganda,” she said.

Morale Operations artist Sergeant William A. Smith carries Betty McIntosh across flood waters in Kunming China, 1945. Alongside them is Chinese cartoonist Tong Ting. The building is the Morale Operations print shop. (Courtesy U.S. Army)

While in training, McIntosh described a visit by anthropologist Margaret Meade, who had done research in the Pacific. She taught them how people in the area thought. “We had to get inside the enemy’s head,” McIntosh emphasized.

On one such operation in 1944, she and fellow OSS officer William Magistretti were posted in New Delhi. Their British counterparts had imprisoned an uncooperative Japanese officer whom they captured in Burma.

“It was toward the end of the war and we were trying to get the Japanese to leave Burma by all means possible,” she said. “But they had been taught never to surrender.”

When McIntosh and Magistretti entered his cell, they found him silent, staring out of his window. Incredibly, Magistretti, who spoke fluent Japanese himself, having attended Japanese university before the war, recognized the prisoner as a classmate.

The POW became convinced to write an order, written by what McIntosh termed a “psycho-styling pen on filmy paper,” erroneously approved by the Japanese High Command in Tokyo, which stated that it was okay to surrender, especially if one were badly injured.

Next, OSS Detachment 101-Burma deployed a Cachin hill tribesman to infiltrate out of the jungle, capture a Japanese courier, kill him, and plant the order in his pouch.

“Within two weeks and for the next six months, we began to notice many Japanese voluntarily surrendering,” McIntosh said.

Though she was not in the European Theatre during the war, she knew well another OSS feat, rewriting the famous German song “Lili Marene,” sung by Marlene Dietrich, another OSS enlistee, with lyrics that were “twisted a bit so that some lonely Nazi soldier, reminded of his country, would hear, “Hitler is ruining Germany.”

Such was the world of black propaganda.

After the war, McIntosh went back into journalism. “What happened to me shouldn’t happen to anybody,” she said. “I went to work for Glamour magazine.”

And she soon found out that her OSS training was an obstacle to her first career.

“I tried, but I couldn’t write a straight news story after the war. I just kept thinking of devious things like `how can I fool these guys?’”

Journalistically restless, by 1949, she found herself back in the undercover world. By then, the OSS had become the CIA, which assigned her to Japan, where she stayed for a year. Her work there remained classified for many years.

She then wrote the book Sisterhood of Spies about the women of the OSS.

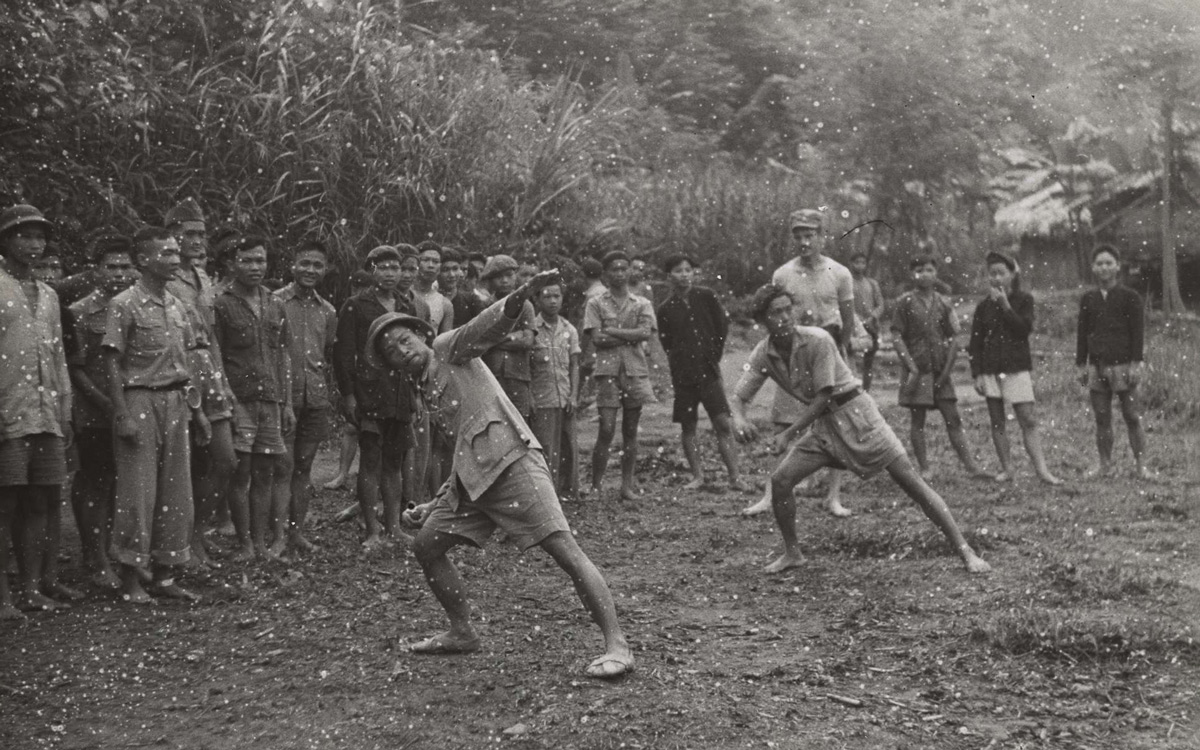

OSS officers watch as Viet Minh practice throwing grenades. (Courtesy National Archives)

Author’s note: This article was updated from a piece I wrote in 1997 for Military Family magazine. (No relation to Military Families magazine).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist whose reportage has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Between 2001 and 2008, Marc served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California. During that time, he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment