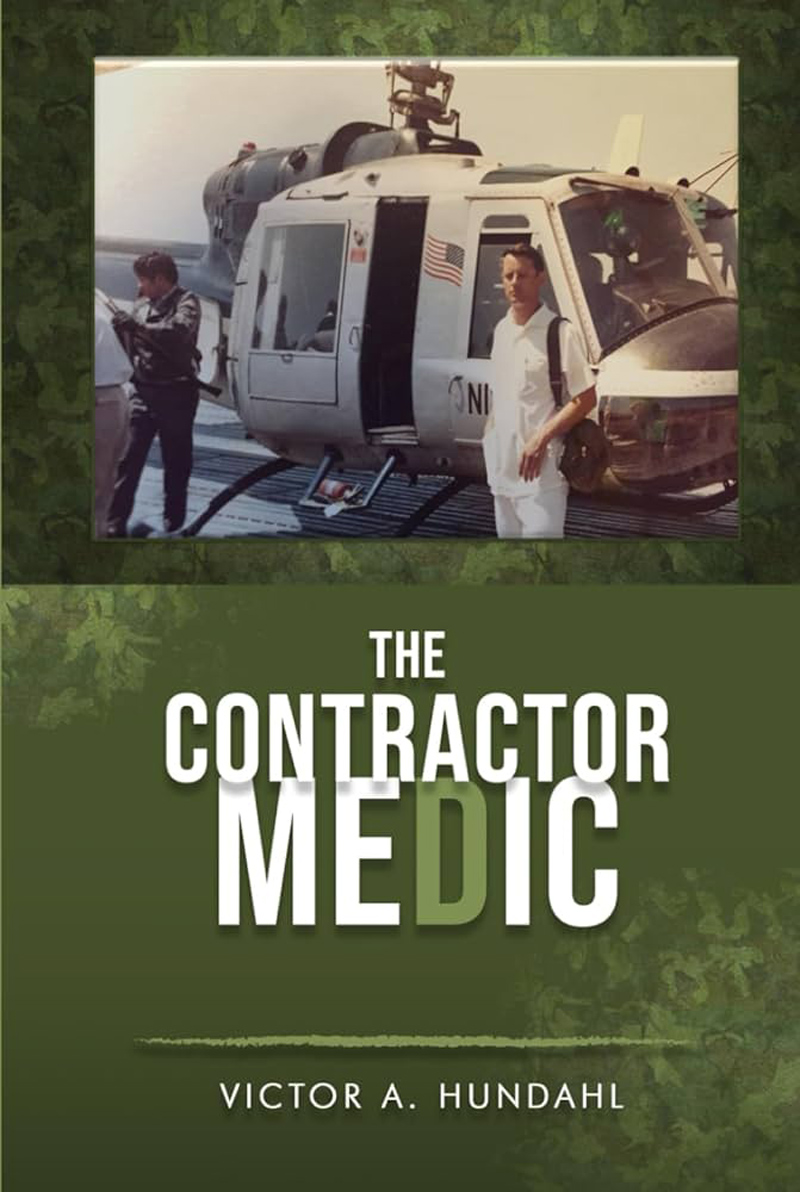

AN EXCERPT FROM:

THE CONTRACTOR MEDIC

By Victor A. Hundahl, The Contractor Medic, The Book Publishing Pros (May 15, 2024), pages 1-7, used with permission

As a civilian medic serving during the war in Vietnam from 1965 to 1972, I had my share of close calls. I found myself in plenty of hairy experiences, often alongside G.I.s who displayed remarkable acts of courage and compassion but who typically remained nameless to me. After serving four years in the United States Marine Corps and becoming a medic with the Montana National Guard Special Forces unit in Kalispell, I went to Vietnam in 1965 as a civilian field medic for the American RMK-BRJ Construction company. I diagnosed and treated diseases, administered emergency care for war wounds and industrial accidents, and performed minor surgeries such as suturing minor lacerations. We acted as primary care physicians to the company employees and others in need in areas where doctors and clinics were unavailable. I was the sole medic treating patients in my clinic. Since I was in a war zone, the most frightening and bizarre events sometimes punctured my relatively routine days.

In early 1969, I received an emergency call at my Chu Lai dispensary, which sat a few hundred yards from the perimeter of the military compound. The highway was rebuilt and resurfaced with asphalt by our construction company and an accident near the construction site.

My interpreter, Nhan, and I immediately left in our white ambulance with its red cross markings. Earlier in the morning, the Army had cleared the road of mines and booby traps, enabling us to speed along in the hot, bright sun. We arrived at the accident scene on the road next to a small Vietnamese hamlet with small thatched huts. As was my habit, from inside the ambulance, I quickly scanned the area, checking out the gathering Vietnamese. I saw five U.S. Army soldiers on a jeep with a mounted machine gun. It appeared to be a tense but orderly situation. Based on experience, however, we knew to be on guard, pulling the ambulance over to the side of the road, I jumped out, medical bag in hand. A small, handsome boy, about eleven years old and clad only in black shorts, was lying next to the massive wheels of an earth mover trailer. The boy appeared dead from the enormous abdomen and pelvic crushtype trauma. With a stethoscope, I examined the boy by auscultation, listening for heart sounds, but found none. His pupils were fixed and non-reactive to light or finger touch. I was careful not to rush my movements to demonstrate care and respect for the boy, particularly given the gathering crowd of villagers.

Nhan and I placed the boy in a green body bag. As I started to zip up the bag, a young girl ran up to put something in the bag. She shoved body parts before my face as I partially unzipped the bag. I realized what they were when she opened her hands to drop them into the bag. It was the boy’s testicles. Somehow, I managed to maintain my composure and zipped up the bag. Nhan and I placed the boy in the ambulance until the village chief could determine what to do with him.

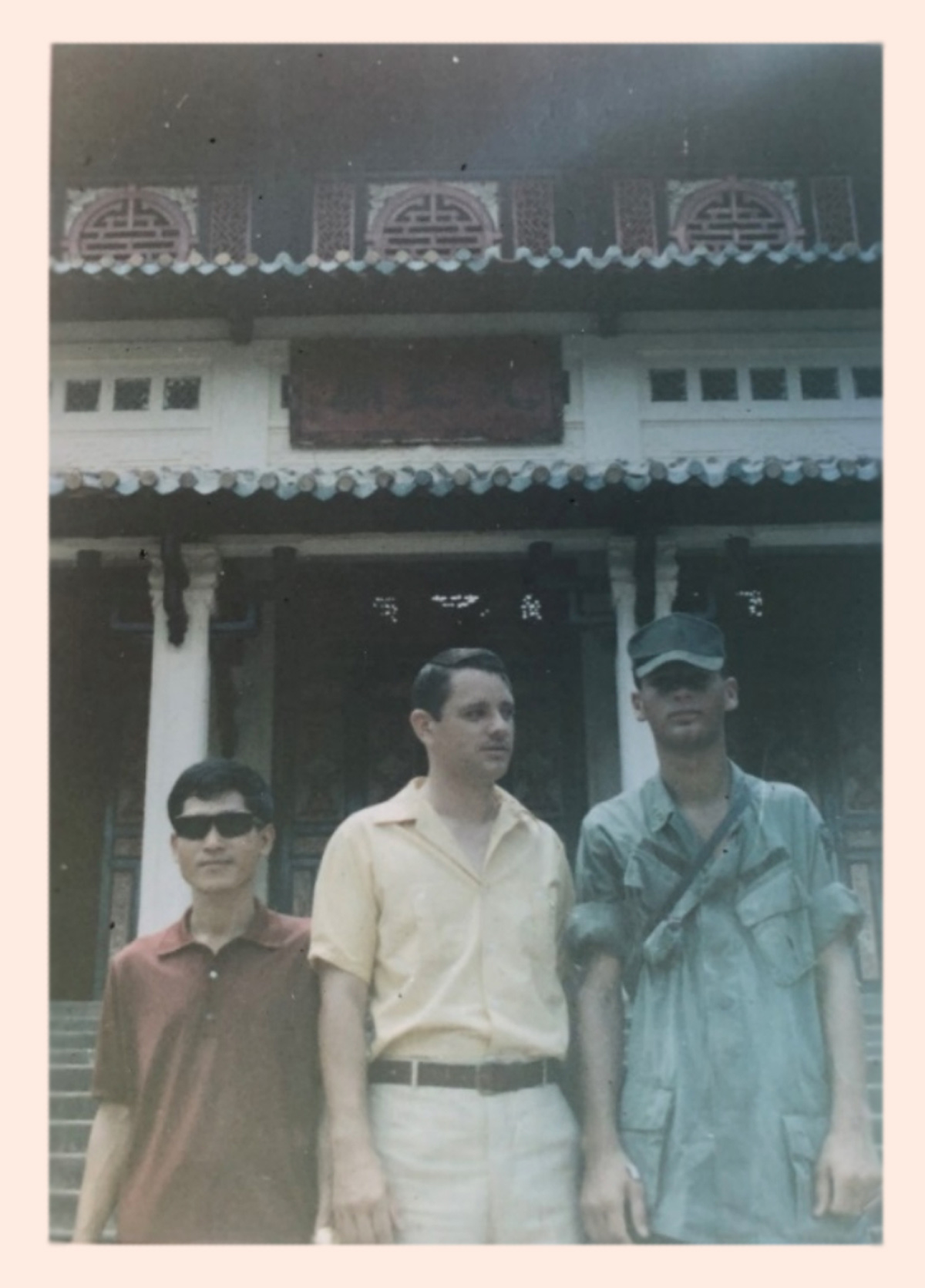

Left: Nhan, Center: Vic Hundahl, Right: Quang, Chu Lai, 1968-1970 (Photo Courtesy Victor Hundahl)

I walked to the hamlet and found a clearing between the thatched huts and the jungle where I could gather my thoughts. Then I saw a frail old man dressed in black pajamas and a grayish, stringy “Ho Chi Mein” beard slowly walking from the cluster of huts toward me into the clearing. He was in tears and howling uncontrollably. I later learned that he was the boy’s grandfather. Suddenly, one of the five American soldiers screamed, “GRENADE!” Now I saw clearly that the old man, arms stretched above his head, had a hand grenade clutched between his hands, his fingers grasping the pull ring. Two of the soldiers ran up and grabbed the old man. As one soldier wrapped his hands around the older man’s hands and the grenade, the other pinned the older man’s arms. A third soldier ran up, an extra safety pin ready to insert into the grenade. In the meantime, l looked around the area for any other hostile action, but the older man appeared to be acting alone. One of the soldiers yelled. “Doc. we need you!” I was already reaching into my medical bag and was preparing a syringe with a sedative. The older man was so small and frail that I prepared half the usual adult dose. I raced to the tightly joined group and swabbed the older man’s arm. I looked up, and in front of our terrified, sweating faces was this grenade, with Vietnamese and American hands wrapped tightly around it. Looking away from the grenade in front of my face, I realized the grass and sky were never so bright with green and blue. A lovely day to die, I thought.

In that instant, it reminded me of the famous picture taken of the Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, only this was not a flag but a live grenade. Another odd thought struck me as I swabbed the older man’s arm. Here I am, by habit and with due diligence, disinfecting the am1 of a man who wants to kill me. I injected the sedative into his upper arm, and the older man slowly relaxed as I supported his lower body. The G.I.s then very carefully eased their fingers under the old man’s and squeezed the grenade handle as another replaced the safety pin and yelled, “Grenade secure!” finally, the old man fell into my arms. Then, led by a small girl, I carried him to a thatched hut and laid him down on a simple bamboo mat. After the village chief took possession of the dead boy and waited an hour to ensure the situation was calm, Nhan and I returned to the Chu Lai dispensary.

I will always remember those G.I.s. Even though I never knew their names, I will always remember their faces. They were so young, in their twenties, but they demonstrated maturity, compassion, and discipline in the face of likely death. I would do almost anything for these G.Is, and I was confident they would do the same if I were in a jam.

The freezing winter wind stung my face as I left the Cessna 180; it was my last free fall skydiving parachute jump at the Big Fork junction in Montana on November 8th. 1965. The frozen ground hit me hard as I did the parachute landing fall. I tried to shake off the shivering cold, gathered my parachute, and walked to the highway to wait for my ride back to Kalispell.

Three weeks later, on November 28, 1965, I stepped off the Pan Am passenger jet at the Tan Son Nhut, South Vietnam Airport, and felt suddenly smothered with the sweltering heat and high humidity, which took my breath away. The climate was at the extreme opposite edge of the cold Montana weather. After customs procedures, an R.M.K. construction company representative took my passport and other documents. Then, I was transported with a few other civilian company workers to a field in the middle of the airport. A company representative told me to pick a tent and cot and stay put while being processed by Vietnamese and U.S. Government agencies. Luckily, the holding area lasted only three days and two nights. Other personnel bad been there for over a week and were still waiting in the sweltering beat. It started a nearly seven-year Vietnam career with the RMK-BRJ construction company, which ended in June 1972.

I never dreamed the Vietnam War would involve my Father and two brothers. My Father would arrive a month or so later to work for RMK-BRJ. Two brothers would follow me, Jess, a Marine, and Peter in the U.S. Army; both would serve a tour of duty in Vietnam. A third brother, Gary, served in the U.S. Army and was assigned to Germany during the Vietnam War. My family would serve ten years of combined Vietnam field service.

Left: Vic Hundahl, Right: my brother Jess, Chu Lai, 1968 (Photo Courtesy Victor Hundahl)

Left: Loi, my driver, Center: Vic Hundahl, Right: my brother Peter (Photo Courtesy Victor Hundahl)

Cam Ranh Bay

The silver Second World War C-47 landed at Cam Ranh Bay, and then I was Jeeped to our company work site on the beach about a mile south of the U.S. Air Force base. It consisted of tents for Americans and other third-country workers and large tents for a mess hall and dispensary. Our shower was a large 50-gallon drum supported by a wood platform with ocean water pumped to it. Due to the two-week monsoon, the ground was sloppy and muddy; our tents and bedding were soaked wet. It takes weeks for things to dry out.

I spent two years at Cam Ranh Bay from November 1965 through January 1968, where I was the sole medic responsible for caring for 4,000 Vietnamese RMK-BRJ workers. I lived and worked in the Vietnamese camp 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the only American to do so. I lived with them and ate what they ate. I trusted my safety with them, and they knew l would give them my best care. The Vietnamese called me “Bacsi Vic” in English, Doctor Vic.

Unlike the American military and political establishments, living in the work camp allowed me to learn about their culture, history, and aspirations. The Vietnamese had conducted jungle warfare for one thousand years against the Chinese occupation until the Chinese withdrew. Using the same hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, they defeated the French at Dien Bein Phu in May of 1954, and now it was the Americans and its ally’s tum to be sucked into the swamp, fighting a competent and determined Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army.

Vietnam existed since 2879 BC and was ravaged by civil wars and repeatedly attacked by China, Mongols, Chams, Dutch, French, and now fighting the Americans. In my mind, the American planners never studied the military history of Vietnam or tried to understand it, nor did they know the South Vietnamese and less the North Vietnamese. Or we were so arrogant that we failed to recognize the motivating factor of the North Vietnamese desire to the South and North Vietnamese again as one nation and one people, against the corrupt Southern Vietnamese government.

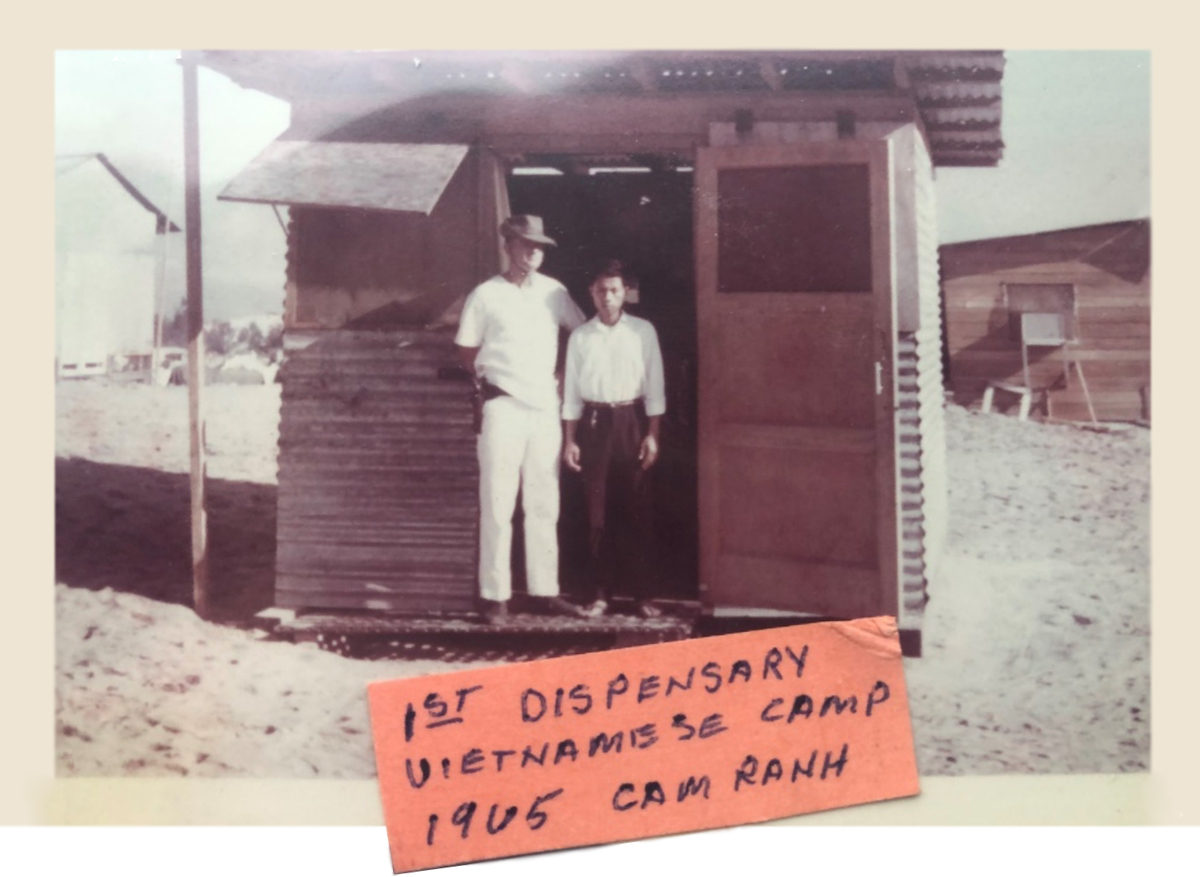

Vic Hundahl and Chinh, Cam Ranh Bay 1965-1967, Vietnamese Work Camp first dispensary. (Photo Courtesy Victor Hundahl)

Left: Chinh, Right: Vic Hundahl, Cam Ranh Bay, 1965-1967 (Photo Courtesy Victor Hundahl)

A young man about 25 came into my small shack bearing a laceration over his right eye. Chinh Coa Minh spoke good English, and I needed an interpreter and someone that I could teach to help me. As I sutured up his wound, we talked about the risks and job duties; I quickly evaluated whether he was a good fit to work with me day and night within the confines of the Vietnamese work camp. He readily proved to be a quick learner, assisting me in suturing wounds and wound care and helping to dispense medications. Never having ever driven a vehicle and eager to learn, I took him out to a field and taught him how to drive the ambulance. Now, I could attend to trauma victims in the back of the ambulance while he drove to a military hospital. Chinh was loyal and worked with me side by side, caring for trauma patients and, at times, the dead—many times under hazardous war-like conditions, for nearly two years while stationed at Cam Ranh Bay.

From time to time, the Vietnamese Army and U.S. Army would raid the Vietnamese camp, arresting V.C. suspects and draft dodgers and recovering weapons and demolitions. I never feared for my safety. During rioting between Vietnamese and third-country nationals, I would be suturing up knife lacerations on arms and hands while mutual combatants sat across from each other, watching me work while waiting their tum. All the while, yelling and fighting were around my wood shack dispensary. After suturing the same Philippine worker on three different occasions during the one day of rioting, I strongly urged him to return to his tent and take a break.

Fortunately for me, all employees accepted that my dispensary was a haven. l became very experienced in diagnosing and treating tropical diseases such as dengue, Q fever, rat bite fever, and malaria. I worked through three plague epidemics with up to 12 Vietnamese patients in my dispensary. I learned to accept the Vietnamese custom of families moving to the patient’s bedside. I let them become involved in their care, cooking, and feeding the patient.

About the Author:

Victor Hundahl, after a four-year stint with the Marines, and medical training with his Montana SFNG unit, Victor spent time on assignments in Vietnam, Johnston Atoll and Africa.

He is a long-time member of the Special Forces Association Chapter 23 Golden Gate Chapter.

Leave A Comment