AN EXCERPT FROM

Tears Across the Mekong

By Marc Phillip Yablonka

From Tears Across the Mekong, published by Figueroa Press (April 4, 2016), pages 15-38, reprinted with permission.

AN INESCAPABLE HISTORY

France had occupied Indochina since the late 1700s in an attempt to spread its empire, benefit from the vast rubber supply and spread the doctrines of Catholicism. Indeed, it had been a French Catholic priest, Alexandre de Rhodes, who had given the Vietnamese their alphabet by combining the ABCs with the tones and vowels of the Chinese characters the Vietnamese had previously used. The French maintained a policy of le jaunissement (the yellowing) and tied that to their mission civilitrice, to convert the “little heathen yellow man” to France’s way of thinking and behaving.

By contrast, the American mission in Indochina was quite different. In Laos, that meant that the United States ventured there clandestinely in order to enlist the help of the highland hill tribes collectively known as the Hmong, and the Royal Lao Army, to stop communist encroachment into Laos. Air America, the noted airline operated by the Central Intelligence Agency, constantly dropped supplies to the Hmong to help in their sustenance. In addition, the United States was clandestinely involved in Laos because the North Vietnamese Army’s major supply route—called the Ho Chi Minh Trail—was actually a system of several routes weaving through the jungles. It was designed to supply the war effort of the then-dubbed Viet Cong guerillas in the south. It extended from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia back down into South Vietnam. In Laos, though bomb craters and unexploded ordnance might prove otherwise, officially, the war there never happened.

The web site www.legaciesofwar.org has a slightly different take on things:

“From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance over Laos during 580,000 bombing missions—equal to a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24-hours a day, for nine years. The bombing was part of the U.S. Secret War in Laos to support the Royal Lao Government against the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Armies. Many villages were destroyed and hundreds of thousands of Lao civilians were displaced during the nine-year period.

“Of the 260 million cluster bombs dropped, up to 30 percent of the cluster bombs dropped by the U.S. in Laos failed to detonate, leaving extensive contamination from unexploded ordnance (UXO) in the countryside. These “bombies,” as the Laotians now call them, have killed or maimed more than 34,000 people since the war’s end—and they continue to claim more innocent victims every day.”

As with every war, there is another side to this story. Australian Vietnam war correspondent Barry Wain, in his book The Refused: The Agony of the Indochinese Refugees, wrote, “In Laos, the takeover meant much the same thing for the Hmong, a minority hill tribe. One faction of the Hmong, with a history of collaboration with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, was marked for annihilation. Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces attacked them in their mountain villages, ambushed them as they fled and pursued survivors all the way to Thailand,” Wain wrote.

“For other Laotians, including the lowlanders, the socialist transformation was not fatal, but deeply traumatic. Thousands were packed off to remote re-education camps. Vestiges of Westernization were eliminated abruptly, and all personal liberties were severely restricted. Private enterprise was strangled, but no alternative system was developed to produce needed goods.”

While the traditionally held view is that American involvement in Indochina occurred between 1961 and 1975, it actually dates back to World War II. Before then, Nguyen Van Thanh, a popular young Vietnamese from the old imperial capital of Hue, under the nom de plume Nguyen Ai Quach (“Nguyen the Patriot”) had written various tracts and poetry to instill a sense of nationalism in his people. By the end of World War II, that same nationalist leader, by then calling himself Ho Chi Minh (“One who enlightens”) sought American assistance in driving the occupying Japanese forces out of his country. That assistance came in the form of supplies and military training from the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), which had evolved into the CIA by the end of the war. Ho Chi Minh remains the most intriguing figure in the Indochina wars of both France and the United States. Quite the world traveler as a young man, he worked as a mess boy aboard a Marseilles-bound ocean liner, as a baker’s helper at the Carlton Hotel in London, and even as fry cook in New York’s Harlem, where it was said, he developed an empathy for the struggle of American blacks.

Looking across the Mekong River at Thailand (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

By 1946, the Japanese were gone and the old colonial power, France, was back in control of its Asian foothold. Ho Chi Minh hoped the same kind of American assistance would be forthcoming in his fight to drive the French from the area. But in spite of the fact that, after Ho returned and his Viet Minh had rescued American pilots shot down by Japanese canon fire during World War II; in spite of the fact that, after Ho returned from the jungles at the end of World War II to reclaim Vietnam, American planes flown with CIA pilots overflew the square in Hanoi where Ho gave a speech quoting from our Declaration of Independence; and in spite of the fact that Ho wrote President Harry Truman three times pleading for American assistance in kicking out the French, that assistance never came.

For after all, by that time Truman’s plate was full with a newly communized China, and a Korean War against communism, Senator Joseph McCarthy leading Red Scare here at home, and a pervading opinion that France, as inept, and in many cases pro-German, as it had been during World War II, was still our ally. Moreover, France was an ally whose own effort in Indochina America had financed. In addition, while Ho indeed was a nationalist, he had joined the French Communist Party in 1924. All of these were factors in Truman’s decision not to respond to Ho’s plea.

Truman, in fact, did the opposite. He demonstrated support for our French allies with American aid totaling $80 billion to finance France’s war by the time its debacle occurred at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. It was at Dien Bien Phu that the French command strategized that all it needed to do was entrench itself at the bottom of a valley near Vietnam’s border with Laos and pick off Ho’s Viet Minh one by one as they descended from the mountains. What they did not know was that by cover of night in the deepest darkest jungle, the cadres maneuvered canons and shells up steep hidden trails on bicycles to the mountain tops. So, at the appointed hour, and for days afterwards, it was the French who were obliterated and overrun, not the Vietnamese. The French surrendered and left Indochina in every way but culturally, as French culture, food and language linger there even today.

Aiding the French at Dien Bien Phu, although no American troops other than American pilots flying French supply planes in the AO (area of operations) took part—(with our financial contribution to the war effort in tow)—was really the beginning of American involvement in Indochina. Not too long after the French withdrew, American CIA operatives began to be more and more prominent. Names like Lucien Conein and Edward Landsdale (once believed to be the model for the Alden Pyle character in Briton Graham Greene’s classic Vietnam novel The Quiet American, about the waning days of French Indochine and the burgeoning involvement of the U.S. in the region, though Greene himself denied it) began to surface. Then, with the election of President John F. Kennedy, came a commitment of Special Forces advisers wearing Green Berets to Vietnam and, secretly, in Laos. (Here it is worthwhile noting that Kennedy’s predecessor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a private meeting before Kennedy moved into the White House, purportedly told the young, new President, “Forget about Vietnam. Laos is your problem.”). What followed was America’s longest protracted and undeclared war lasting through four presidencies in which over 58,000 Americans and over three million Vietnamese, an estimate one to three million Cambodians and untold numbers of Laotians lost their lives.

After the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, and the toppling of the regimes we supported in Cambodia and Laos that same year, out of a sense of responsibility, caring and guilt for abandoning them, the United States and other countries such as France, Canada and Australia (with its own past in Indochina in tandem with ours) undertook the massive task of resettling millions of Indochinese refugees displaced by the war in Southeast Asia. Millions of escapees from the new communist order, many who had worked and fought alongside Americans, were resettled in those and other countries—300,000 in the United States alone. But before being resettled in third countries, they had to endure further tribulations and terrible tenures in United Nations-sponsored refugee camps in Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines.

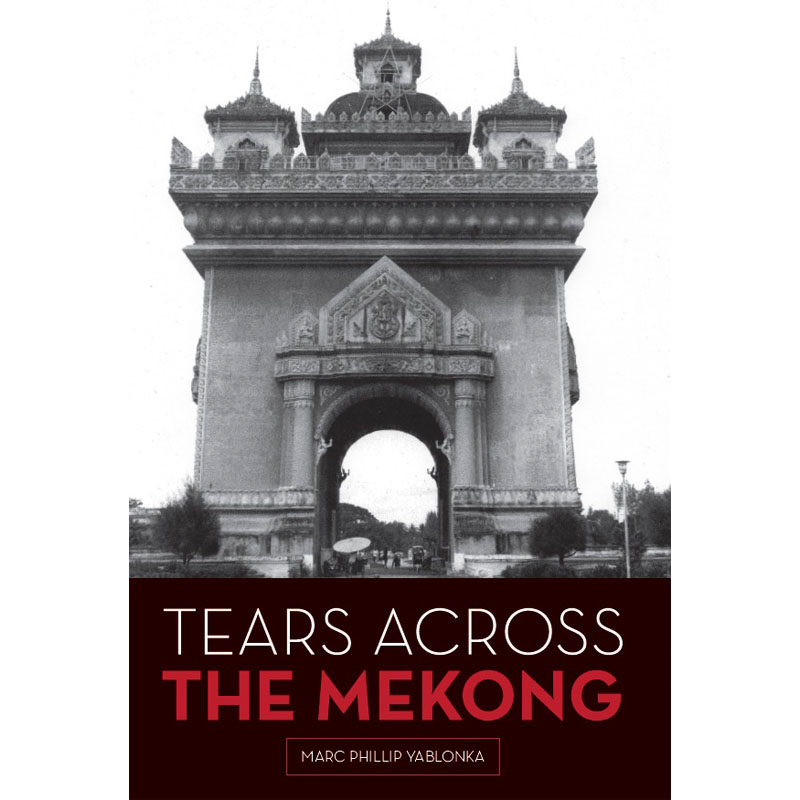

The Patuxay Monument—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Like their fellow refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia, the Laotians packed real and emotional suitcases before coming to the U.S. The most common emotion they all shared was fear. Naturally, countless among them had been terribly abused both by the communist system they’d fled and by those who controlled the refugee camps in Thailand. Although the Lao had undergone acculturation training before coming here, in reality they knew little about the new world that had inherited them just as they had inherited it. The memories of their past, from the 1970s through the `80s, when the Lao had to fight for their lives, underlie the entire Laotian experience. Thousands of Lao sent to re-education camps dubbed the “Seminar” (supposedly a one- or two-week imprisonment that ended up lasting up to ten years or more) did not survive. The sponsors of the Seminar, brothers to the Viet Cong and Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge, who were known as the Pathet Lao, fooled their fellow Lao into thinking their stay would be educational. The only lesson they learned was just how cruel man’s inhumanity toward his fellow man can be. Lao in the camps, especially those who worked with the previous regime, spoke French, wore glasses (indicating they were intellectuals), were teachers, doctors, or other professionals, were by virtue thereof, enemies of the state and were often tortured to death.

Most who were released or escaped from the Seminar also found a myriad of trauma awaiting them upon return home. They faced suspicion from relatives, neighbors, and friends simply because they had been incarcerated there. The Pathet Lao were everywhere watching people, waiting and ready to jail and kill them at the slightest negative comment about the new communist regime. If persons who had been in the Seminar could get beyond that, the next obstacle was being able to clandestinely arrange a getaway into neighboring Thailand. Would their plans remain a secret? Would a Pathet Lao cadre knock on their door one midnight prior to an escape for which they paid a Laotian in gold? The next great barrier was nature itself. To get out of Laos, one needed to traverse the Mekong River. Currents had to be uppermost in the minds of parents with children who could not swim. The boats escapees either bought or commandeered were flimsy at best. What’s more, the same Thai pirates that sailed the South China Sea robbing, raping and killing Vietnamese and Cambodian boat people plied their same trade upon the Lao attempting to cross the Mekong.

Once they got beyond the grasp of the pirates, the Lao thought they would be free and secure inside Thailand. Untrue. The United Nations-run and Thai staffed camps in Thailand as well as those in Malaysia proved to be hotbeds of corruption. Said the refugees, they were not fed properly. Nor did they receive enough water to drink or bathe in. Money sent to them from relatives already in the West was cut into by camp “bankers” who demanded a percentage or else. Communist agents were allowed to fester among the refugees threatening them with death unless they returned to their former countries. Owing to a continuum of bureaucratic red tape, refugees were forced to live in primitive lean-tos for years before being repatriated to a third country. Of course, the Thai government denied that any of this ever occurred.

THE HMONG AND THE CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency and U.S. Army Special Forces had a vested interest in propping up the Hmong Hill tribes and, without a doubt, the most famous Hmong tribesman of all, the Royal Lao Army’s General Vang Pao, a chieftain. He was purportedly paid large sums of money to recruit fellow tribesmen to fight alongside the Agency and the Special Forces in Laos in “SGUs,” or Special Guerilla Units. The Agency enlisted Vang Pao in an effort to stem the tide of the North Vietnamese-supported communist insurgency there promulgated by the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army, itself spilling into Laos. In exchange, the Hmong received much needed weapons to protect themselves along with all the rice they required. Directly after the war, the CIA, Department of State and Immigration and Naturalization Service went out of their way to aid the Hmong in their resettlement in the U.S. as a thank you.

Among the CIA agents first to make contact with Vang Pao was Anthony Poshepny, known to those who knew him as Tony Poe, codename: Agent Upin.

In early 1961, Poe had parachuted into the hills of Laos to train Vang Pao and his fellow Hmong in their fight against the Pathet Lao communists during the civil war then occurring in Laos. Some accounts claim the CIA’s intent was to support Vang Pao’s connection to the opium trade in Laos, while others say the general’s connection to the drug is what severed the relationship between Poe and Vang Pao.

“Tony was a heavy drinker but the whole drug dealing/opium crap is mostly BS,” said a friend of Poe’s from their time together in Laos and who chose to comment anonymously. “These stories have been around for a long time and the Mel Gibson movie on Air America only reinforced them. Did Vang Pao and the CIA aid in the opium business? Yes, in that it was the only cash crop of the Hmong. Did opium move on U.S. aircraft? Yes, but it was not a major U.S. government-sanctioned operation. Vang Pao did not need the cash from the drug trade. The CIA had a C-130 loaded with cash flown into Long Tieng monthly.”

Poe stayed in Laos until 1970, when the CIA relocated him to Bangkok. During his years in Laos, he married a Hmong princess and—legend holds—kept pickled heads of Pathet Lao in jars of whiskey. He was reported to have offered 5,000 Lao Kip to any Hmong soldier who would bring him the ear of a communist Pathet Lao, an offer which did not particularly please his superiors. According to the web site http://www.nndb.com, whenever they would challenge his kill counts, he would package up the ears and send them to the CIA station in Vientiane.

One day out on patrol, Poe saw a young boy with no ears. When he asked how this could have happened to the lad, he was told that the boy’s father had cut them off in order to get 10,000 Kip from Poe. This greatly disturbed Poe, and from then on, legend holds he would only accept severed heads in exchange for the reward.

“I don’t know anything about the heads,” stated the anonymous source. “But he did have a jar of pickled ears.”

Though Tony Poe was rumored to have been the model for Marlon Brando’s character Col. Kurtz in the film Apocalypse Now, director Francis Ford Coppola and Poe both denied this.

“That wasn’t me,” he told the web site www.laoveterans.com. “I didn’t contradict orders. Everyone says I got too involved with the locals. I say, `Hey, that’s leadership.’” Poe, who had had several fingers amputated, died in Sonoma. California in 2003 of heart failure.

Aiding Tony Poe and other CIA operatives from the skies over Laos, as it did over Vietnam and Cambodia, was the noted airline Air America. Air America had evolved out of post-World War II Taiwan-based Civil Air Transport, which was sold to the U.S. government and consigned to the CIA. It was manned by pilots and ground personnel, most of whom had seen military service going back to World War II Korea and certainly Vietnam. Its mission in Indochina was to go where the military could not or refused to go, whether in the fixed-wing Pilatus Porter, C-47s or Huey helicopters. Missions ranged from rescuing down pilots, and transporting Hmong warriors into battle to resupplying Hmong outposts with weapons and ammunition. The reputation of Air America and its brave personnel was besmirched almost beyond reparation after the war by media and cinema alike. Many Air America alumni are still fighting to correct it

The Russian Embassy—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Reaction to American use of the Hmong during the war in Laos was not regarded favorably in all circles at the time. Judith Luther, then a social worker with the United Cambodian Community social service organization, was one who was angered by the use of the Hmong to fight the Lao and North Vietnamese communists. “In all their history, the Hmong never crossed their borders in war. That never happened to them. They are not at all a warlike people. That was something imposed upon them. Once it was, they turned out to be incredible warriors and the CIA really exploited that. As a consequence, they were virtually wiped out.”

Charlie Waters, a veterans advocate from Fresno, California, home to one of the largest Hmong communities in the United States, sees it differently, however. “The Hmong worked with us for 15 years, and lost in excess of 30,000 troops fighting for the United States. This is the least we can do to begin to pay you back for the service that you did,” Waters said at a recent Fresno rally in support of Vang Pao and his fellow Hmong soldiers.

Fresno area leaders are lining up in support of a bill, introduced by Congressman Jim Costa and 22 other representatives, which would recognize the Hmong soldiers as American servicemen. That, in turn, would allow them the right to burial in a national cemetery in the United States. Meanwhile, surviving Hmong vets say they are honored. “The most important thing is we want to be recognized as American soldiers. We shed blood in the Vietnam war to protect the American country, please recognize that,” Hmong veteran, Bhou Vu recently told KMPH-TV, Fresno through a translator.

“It’s fitting and proper that the United States recognize those of you who are still here, with an appropriate honor for your service to our country,” the Congressman said at the rally. He spoke before some of the nearly seven thousand Hmong veterans alive today who would qualify for a military burial.

Steve Schofield is a retired Army Reserve major from Sheboygan, Wisconsin. He was a Green Beret combat medic in Vietnam in 1968, who served with SOG, the Studies and Observation Group, troops who conducted cross-border operations into Cambodia and Laos. Later he worked as a civilian medic with the U. S. Agency for International Development in Laos between 1969 and 1975. Schofield believes he holds the key to our collective understanding what the Hmong should mean to us if they don’t already:

“The main message is to educate…because so few people know,” he recently told his hometown newspaper the Sheboygan Press. “The Hmong suffered tremendous casualties. Twenty percent of the male population was killed in that war. Anyone that’ll listen to me, I’ve talked about [the Secret War],” Schofield said. “Most audiences I spoke to have been very receptive and of them say, `I had no idea. I just didn’t know.’”

The Light at the End of the American Tunnel

To this day, fear of death pervades among the Hmong hill tribes’ people who were never able to get out of Laos, though the Hmong who are here and the lowland Lao have worked to surpass that fear. While it has been harder for the Hmong who still fear for the welfare of their families and fellow Hmong remaining in Laos, all of them, mountain people and lowlanders, will never forget the fear they felt. It must appear in their dreams constantly, although they have tried to move beyond it. They were and are arresting in the gentleness that shines from their faces. They are extraordinary in the sense that, with all they have lived through, they are still able to retain harmony, their most important principle. In interviewing them, I found them truly peace-loving. They have an unbreakable will to survive in the West, but at the same time, keep intact the customs with which they grew up in Laos, however difficult a chore that may have been for them then. Their problems were indeed many, but their resolution has seen them through.

THE LONG, LONG JOURNEY OF BOUNLIENG PHILAVONG

From 5:00 until 7:30 every morning, from 1975 through 1984, Bounlieng Philavong did what he called “crazy things.” Sentenced to what the ruling Pathet Lao communists paradoxically dubbed the “Seminar,” he leveled hills with a shovel so he and other prisoners could build bamboo huts. He dug up old roads which were never repaved. He would then return to Camp 06, two hundred miles outside of Sam Neua, northern Laos. He returned every morning for Marxist indoctrination, which he likened to a concentration camp.

In the afternoons, the tanned, soulful-looking Lao cut wood in the distant forests and then returned to camp with the timber piled high on his back. Then, he was invariably ordered to grow rice, degrass fields, or cut still more lumber. Late each night, he returned to one of the 24-bed unwalled hootches which he shared with 50 men. The next morning, the cycle started all over again.

His routine stayed the same for every day of the nine years he spent in the Seminar. He lived on bug-infested rice plus whatever birds, mice, and snakes he could catch to supplement his diet. All of this, and the daily doses of Marxism he was also forced to ingest, was almost too much for him. “I was almost driven insane by communism,” Bounlieng says.

The son of a lawyer and a typical Laotian housewife, this native of Pakse, southern Laos, speaks of his country almost idyllically. His eyes begin to mist. “Life under the French regime was easy.”

It was an easy life where salaries were only sufficient. Working for the government was the objective of many Laotians like Bounlieng. Those that did got much prestige but less money, he said.

That life came abruptly to a halt in 1954, just as it did in neighboring Vietnam. The Geneva Accords of that year divided Vietnam into a communist North under Ho Chi Minh, and an American-backed South presided over by Ngo Dinh Diem, a Buddhist-hating Catholic. But Laos was untouched by any divisions in country and was “very beautiful then. The trees, the rivers, everything was natural. Then the (Viet Minh-backed) Pathet Lao communists changed the concept of beauty by changing our mentality,” the French-educated, Vietnamese-speaking Bounlieng asserts. “There was no more self.”

The Young Years and Early Manhood

When he was young, many of Bounlieng’s teachers were Vietnamese owing to the fact that in those times, as even today, the two countries, Vietnam and her “little land-locked brother” Laos, were politically and culturally close. “They loved me very much. I worked very hard every day and received the best marks among all the Lao and Vietnamese in class.”

His teachers at the French lycée in Laos’s capital Vientiane felt the same way. They admired him so that they used to take him home and feed him though he is nonplussed by their actions. “I don’t know why they did that,” Bounlieng says.

“When the French came to Laos, they didn’t want to leave because they found our country so beautiful and the people so peaceful. Life there was easy for them.”

His lycée instructors encouraged his studies so much that he went on to pursue advanced degrees in economics and finance in France and Switzerland. He had planned to follow in his father’s footsteps and study law, but those plans were interrupted by a fateful decision to return home.

1960s Laos

Feeling political urgency, Bounlieng came back to Vientiane in 1966. The government had been in turmoil since 1960, when a little-known Royal Lao Army paratrooper, Gen. Kong Le, instituted a coup d’état in Laos. Upon the French withdrawal from all Indochina in 1954, Laos saw a shift from French to American influence; this while President Eisenhower occupied the White House. With the election of President John F. Kennedy came a shift in concern in Washington, D.C. from Laos, which Ike had warned JFK about, to Vietnam, which he had been eager to showcase on the rebound after the disastrous Bay of Pigs incident in Cuba, where CIA agents and Cuban exiles attempted to overthrow the regime of Fidel Castro. He did this by sending in American advisers, an elite unit of Special Forces personnel who wore, and were known as, Green Berets.

Soon after returning home, Bounlieng accepted the job of Chief Inspector/Auditor of the Royal Lao Ministry of Finance. But he grew dissatisfied with that job and soon moved over to the Laos’s national airline, Royale Air Lao, where he became the Director of Finance.

The Communist Takeover

In 1975, as it was with Vietnam and Cambodia, Laos fell into the hands of a communist régime, the Pathet Lao. And, as it was with Laos’s neighbors, the new régime felt intellectuals, doctors, government employees and military personnel who thrived under the previous Royal Lao regime were “disturbing,” as Bounlieng spins it mildly. They suspected those who wore glasses, since bespectacled people painted a picture of intellectualism that the Pathet Lao despised yet feared at the very same time.

“With communism, the Pathet Lao ruled everything and everybody. They ruled every word we spoke. People’s mentality was one of physical pressure,” Bounlieng stressed, “but communism hasn’t developed since the Vietnam War. Nobody wants it anymore.”

But in `75, communism wanted Bounlieng enough to cart him off to the Seminar, and the reality of that experience hit Bounlieng and all non-believing Lao very hard. Throughout Laos’s long and rich history, they were always mediators of conflicts between the centuries-old nation states in the region: Tong King, Annam, Cochin China, and Champa (modern day Vietnam), the Khmer (Cambodia), and Siamese (Thai). The principle of harmony being foremost among them, the Lao were always accommodating of their fellow Southeast Asians. That ceased in 1975.

“We did not suspect what was going on. We did not know how to be,” Says Bounlieng. The communists pulled out those who had served Laos faithfully. They extricated those, like unsuspecting Bounlieng, who had previously actually been willing to work alongside the Pathet Lao. In his mind, the thought of a coalition government was acceptable, since many of the high echelon officials of the Pathet Lao had been his schoolmates back in France. He observed a certain challenge in working with them. He even admits, “I wanted the communists to succeed!”

“If you belonged to the former régime, your conception became theirs. We didn’t think about Soviet or Vietnamese communism. We thought that, if it was Lao, it was good. It was still Lao, so why not work together?” he asked himself at the time.

Tears Across the Mekong author Marc Yablonka with young Buddhist bonzes—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Phaly Pao)

The Seminar

The communists promised Bounlieng and hundreds of others in the government they would all be able to maintain their same positions after learning the new system’s ways at the Seminar. Of course, nothing of the sort ever happened. “The Pathet Lao were clever liars. We were captured by the very word ‘Seminar,’ so most did not flee. That even in spite of the secretive warning given Bounlieng by his friend, the Minister of Travel, of the truth he would soon learn.

In July 1975, Bounlieng was ordered to his first Seminar at l’école Normale (the teachers college) in Vientiane. “We saw reality very quickly. We were already frightened by the time we had flown to Xieng Khouang. Tanks met us. They were posted in positions so that we could not escape. We began to have the idea that we were not being sent to `study’ in the Seminar at all.”

The Pathet Lao, Bounlieng remembered, separated those who had been in the Royal Lao Army, those who had been police, and those civil servants who had worked for the government. Bounlieng was on the latter.

The Pathet Lao had told those it was carting to the Seminar that they would be given a full ceremony upon arrival. However, when Bounlieng deplaned from the 50-seater Caribou prop that had stolen him away from his family and work, he and his fellows were met by one solitary Russian military vehicle commandeered by an unranked Pathet Lao soldier. No “ceremony” ever took place.

“At that point, I realized that what a friend aboard the plane had told me was true. We were,” he hesitates for a second and reverts to his second language, “les prisoniers.”

Bounlieng was then shuttled from one Pathet Lao re-education camp to the next, all within a matter of days. From the camp at Xieng Khouang he was deposited into another at Vieng Xay. These camps were holding tanks in typical Laotian villages with bamboo huts, a few brick buildings and perhaps a hotel.

The worst of his incarcerations came when he was transferred to Camp 06. He was devastated. “When I got there, I saw the camp was,” again he drifts back to French, “éntouré de fils barbelés” (surrounded by barbed wire).

At 06 Bounlieng soon learned the Pathet Lao were in the habit of circulating the laborers from one group to another every few days. “This drove us crazy. By doing so, the prisoners could never quite build up enough trust in one another to confide and conspire. “Everything was secret,” he said.

Early in his imprisonment, Bounlieng realized that the only way to survive was to cooperate with the Pathet Lao, which is exactly what he did, but he never once trusted their motives. “I had to survive the detention and not make a mistake again. Some thought about escape, but I didn’t because I knew that I would get caught. Those who ran were often spotted by villagers whose sole duty it was to report them. If they chose not to, and they themselves were caught, they would be sent to the Seminar as well.” Then they would be forced to undergo the same re-education glorifying Marxism. If that happened, they would often hear, “Comrades, your group will do such and such,” Bounlieng remembered. While the prisoners were all “comrades,” that name could never be applied to the Pathet Lao superiors. Prisoners were under strict orders to address them as “uncle” or “brother.”

“Everybody away from home thought only about going back home. The more they thought about home, the more crazy they became. We were not animals. We were human beings, but they treated us like animals.”

The Pathet Lao told us, “All of you, do not think about Vientiane anymore. Think only about the Party. There is no `self.’ Everything is for all.”

Bounlieng’s wife paid a surprise visit to him only once. He forbade her from coming again. “I didn’t want her to see me in the camp. I tried to work and stay active, but I just didn’t think.”

Then, in 1984, without warning, to Bounlieng’s total disbelief and happiness, most likely because he had been as cooperative with the Pathet Lao as his mind and body would let him be, he was informed that he had been placed on a list for “immediate release.” However, that “immediate release, typical of the Pathet Lao, evolved into an almost unbearable wait of several months. Eventually though, he was freed, and he returned to his family in Vientiane.

Home Again

When he returned home to Vientiane, Bounlieng was shocked to learn his wife had become a Pathet Lao collaborator. Even with that knowledge, he still asked his wife to escape Laos with him and their four children. She refused, Bounlieng understood, because she had a brother in the re-education camp and because she did not want to leave her parents behind. He could not countenance his wife’s favoring and remaining in a country whose ruling régime had imprisoned him for nine years. Had she been brain-washed? Bounlieng does not think so.

By 1984, thousands of people had already fled Laos. Those numbers included vast thousands of Hmong tribes people who been instrumental in aiding the Central Intelligence Agency in their fight against communist insurgency during, not only the Vietnam War, but also the “secret war” that occurred alongside it in Laos. It was a war that few journalists got clearance to cover and so, on paper anyway, it was a war that never happened.

Meanwhile, all of Bounlieng’s friends had become strangers. They did not trust him, nor he them. It was a feeling of mutual suspicion. He suspected and felt suspect to others. “It was not the same. The Party had eyes.”

The Party forced this educated individual to work as a street cleaner some nights and to man a gun functioning as a gendarme on patrol on others. The “comrades” whom he had been with in the Seminar were all gone. Everywhere were new, untrustworthy faces, faces he had never seen before. He dared not talk truth with any of these people. “I was frustrated. When we talked, it was only about the Party. Not what we were really thinking.” They were terrified of being turned in to the communists. After the third night on guard duty, Bounlieng had had enough. “I had to go away. I could no longer trust my neighbors. Even fathers, brothers, husbands and wives were reporting each other. If that had happened to me, suicide would have been a happy solution.”

Escape to Thailand

Bounlieng now had to think quickly and secretly. With the political climate continuing to heat up in Laos, he began to fear for his life. He decided, with the help of his uncle, also a recent detainee of the Seminar, to escape. His plan was elaborate. They decided to take the eldest of his four children, his then 17-year-old son Phouttasak, whom he knew would understand. Together the three of them plotted to trek across the Mekong River into Thailand. “We couldn’t tell anyone else that we planned to escape. We couldn’t make another mistake. My son agreed to go on the condition that we immigrate to France. I promised him,” but that was a promise that Bounlieng was unable to keep. His son did not begrudge his father that because he owes his life to him.

Bounlieng’s uncle contacted a middle-man, who contacted yet another middle-man, who, in turn, contacted a taxi driver who picked them up at the appointed hour of the day they decided to flee. All of these transactions set them back 5,000 Thai Baht, a much more sought after currency than the almost worthless Lao Kip. The cabby arrived at Bounlieng’s parents’ house at two o’clock in the afternoon. “People would be going back to work then after the siesta. No one would suspect us.”

Bounlieng’s parents, whom he had decided to tell after all, were crying bitterly. “I received their blessings and they gave me five small Buddhas to protect me on my journey.” He wore those Buddhas around his neck hidden in a blue crocheted pouch throughout the escape. They remain in that pouch to this day. And when he produced them, thoughts of the parents he left behind cloud both his eyes and his mind.

Before escaping, Bounlieng ironically, perhaps daringly, put on spectacles (the Pathet Laos’ symbol for intellectualism) and a hat so that he would not be recognized. Together with his son and uncle, he bid his parents good-bye and set out toward the Thai border. He slipped away in the direction of freedom never telling his wife, youngest son and two daughters good-bye, though his youngest son later escaped Laos himself along with a former colonel in the Royal Lao Army.

There were several check-points along the way however. The first was a house seven miles away at the edge of the Mekong. Six tension-filled hours awaited them there. A canoe was to have been awaiting them. It wasn’t. More Thai Baht had to be paid for that. While Bounlieng waited, he asked himself, “Why does the sun take so long to go to sleep tonight?” Finally a canoe was located and they shoved off; however, the current of the Mekong proved too strong and they were forced to beach the craft on an island in the middle of the river. In retrospect, it was an island that saved their lives because, had they continued trying to cross the river, they might have capsized and Bounlieng’s son could not swim. “We all might have died,” he said.

They reached dry land, but they were not out of danger. Soon they fell prey to Thai pirates—notorious for robbing, raping and killing many of the boat people fleeing the grips of communism in Southeast Asia—who were there to bid them a frightening welcome. The pirate’s vessel had been waiting for them in the dark shadows of some out-of-the-way cove, and when Bounlieng’s boat hit the sand, the first thing they heard was the loud voice of one of the pirates ordering them to stop. The middle-man who had provided the canoe told Bounlieng, his son and uncle to hide in the sand beside the canoe.

Vietnamese woman with dinner—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Bounlieng, at first, thought the whole thing a set-up on the middle-man’s part and was ready to kill him. It wasn’t. Anyway, the middle-man’s life would soon be the least of his worries. “I thought to myself, `To kill must be easy, and they are going to kill me now.’ I was so close to death.”

The pirates forcibly escorted them deep into the island to a plantation. From there, they were brought to a small cabin for interrogation. Bounlieng and his uncle pleaded with the pirates not to harm them. They swore that they had nothing of value on them and that all they wanted was to escape Laos. They tried to bribe the pirates with chocolates, bread, cigarettes, whatever they had, but that did not work. The pirates separated all of them and cross-examined them one by one. They asked the three how many Thai Baht they had with them. Luckily, prior to escaping, they had all memorized an erroneously low amount should such a scenario befall them. Equally lucky, the pirates never found the majority of their money which they had hidden in the soles of their shoes.

“I saw one of the pirate’s swords dangling inside the cabin and I thought how many people had already been killed by it,” Bounlieng remembered. He credits the fact that they had purposely dressed as peasants with saving their lives.

“I thought I would die that day. I thought to myself, `If I don’t die today, then I will never die.’”

The experience with the Thai pirates and the fear they caused in him taught Bounlieng a lot and it guides his life even today. “There’s so much in life. I was so close to death. I knew that I might be afraid later, but I had already been close to the edge. Today, I feel that if I die, that’s just fine.”

Miraculously, the pirates escorted them to the Thai border at Tha Bo…but not before fobbing them of 9,000 Baht. “With Thai pirates you could expect anything,”

Eighteen long and treacherous hours later, they were inside Thailand—they thought safely. They paid another 1,000 Baht to buy bicycles, the only available transportation, to get from Tha Bo to Nong Khai, where a distant cousin of Bounlieng lived.

The Refugee Camps

At Nong Khai, the trio thought they were doing the right thing when they reported to the police. However, when Bounlieng announced their intent to reside with his cousin, Thai hands were out for another bribe: an additional 1000 Baht just to keep them all from being locked up in jail for good. All three were then ordered to enter the refugee camp there immediately. There would be no residing with his cousin whatsoever. “It did not take us long to figure out that corruption with a capital C was Thailand’s middle name,” Bounlieng said.

For the next year, Bounlieng’s experiences in Thailand were not that much different than those he had in the Seminar in Laos. From Nong Khai, they were sent to another refugee camp called Nopho in Nakhonephanonh, where they and thousands of other Indochinese refugees underwent the screening and relocation process. “It was another hell. There were double rows of barbed wire all around the camp, which, if you tried to leave, they would jail or shoot you, he recalled.

The rooms at Nopho were built to sleep four, but there were no beds. Six to nine people were often crammed together. The Thai in the neighboring town went from being dirt poor to enterprisingly better off in no time at all. They sold wood through the barbed wire fences to the refugees there. From this timber the refugees constructed beds to add to the pillows, blankets and mosquito nets they had been given upon entry. Those lucky enough to afford cooking utensils built kitchens outside of their makeshift huts. All of them barely survived with very little meat, spoiled fish, rice, sauce and oil that had been provided by the United Nations, which oversaw most of the refugee camps in Thailand. “We didn’t receive enough food,” Bounlieng said, lashing out at the UN.

His only satisfaction at Nopho came from the fact that he was able to be with his son. But his son brought him anguish at the same time because he yearned to get out and go into town. “We were illegal. If the police caught him, that would have meant trouble. I worried so much,” he said.

The violence that Bounlieng thought he had left behind in Laos caught up to him again in the refugee camp in Thailand. “There were even communists inside creating problems. Everybody who arrived at the camp wanted to get out and many even lied, fabricating stories about connections to the U.S. government in order to do so. The communists in the camp took advantage of the situation and spread rumors that we would have to live in the camp forever, that the camp itself was going to be moved deeper into the mountains, or even that no countries would take us.”

Impoverished houses—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

If fear of the “in-house communists” wasn’t enough, there were even youth gangs roaming the camp robbing and accosting their own people.

When asked to respond to these charges, Second Secretary of the Thai Embassy in Washington, D.C., Jukr Boon-Long took strong exception to the many accusations leveled at his country by a multitude of Indochinese refugees however. “We have a lot of problems with the Lao screaming that the screening process is unfair. The UN High Commission for Refugees has had no report of complaints from Bangkok. I don’t think the Lao know what they are talking about. The system works well,” he said.

But not for Bounlieng, who countered that many of the refugees remained afraid to complain because they did not want to jeopardize their chances for resettlement. Also many who had made it out still had relatives residing in the camps whose chances to be released they didn’t want to effect negatively. Hence, no one would ever have dared file a complaint.

The New York-based Lawyers Committee for Human Rights sided with Bounlieng. “Screening was conducted in a haphazard manner with little concern for legal norms. Extortion and bribery were widespread. And despite the observatory rule, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Thailand proved incapable of ensuring a reliable and fair procedure.”

Bounlieng remained incensed by his treatment for years after and was heard by this writer to warn the Thai and the UNHCR, “They will have trouble one day. They will receive the same treatment.”

Bounlieng grew quickly tired of life at Nopho. “I told myself that I would go to any country that accepted me: Japan, New Zealand, Australia, I didn’t care. I just did not want to wait anymore.

“It was a prison. It was worse than the Seminar because at least we could eventually leave.” Not the refugee camp, though. Any refugee who wandered outside of the camp except to buy food at the market between noon and 2:00 o’clock would be put in jail. If that happened, three hundred Baht needed to be shelled out in order to bribe one’s way back into the camp, Bounieng remembered.

Water for washing, bathing and cooking was rationed daily, Bounlieng reiterated. “We didn’t even have enough to wash ourselves. They treated us like animals.”

Nopho had been built to hold 15,000 refugees. By the time Bounlieng arrived there in 1984, however, 42, 000 Indochinese were shoved together in the camp. Corruption, as the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights attested, was indeed rampant. Any money sent from abroad to the refugees passed literally through the hands of the “camp banker,” who invariably took his share when converting the USD or French Francs into Thai Baht. “They called it a commission,” Bounlieng mused.

Young beggar girl leading her blind father around—Vientiane, Laos (Photo courtesy Marc Yablonka)

Resettlement Process

It took Bounlieng, his son and uncle almost a year to get out of Nopho. For others, the process took years. Bounlieng’s previous connection to the Lao government gave him the status of P-4. It wasn’t the best, P-1. But it was high enough for Bounlieng, his son and his uncle to emigrate out of Thailand for good. Bounlieng said with a great deal of bitterness that it was entirely possible for a refugee that had been a janitor at the U.S. Embassy or a clerk at the PX on a U.S. military installation in Vietnam to receive P-1. At the same time, an educated person, such as himself, did not have as easy a time departing the camps.

Remembering the promise he had made to his son before escaping Laos, Bounlieng planned at first to go to France. However, the French only allowed those with parents or grandparents already settled in France to immigrate there. The two brothers Bounlieng had living in Paris and Toulouse were not direct enough ties for the French government to approve him. Ironically, as he later found out, having those brothers in France almost disqualified him from being accepted by the U.S. government, whose philosophy at the time was that refugees would have an easier time getting accustomed to life in the West if they were resettled in a country where any family members resided. American immigration officials were prone to denying many applications from refugees, like Bounlieng, who fit that profile. For him, any refusal would have meant more time—undoubtedly years —in the camps.

In applying to resettle in the States, he purposefully neglected to mention his brothers in France. He feared that to do so would mean the French would once again be in control of his destiny, a vicious cycle would occur because his brothers were not close enough kin to allow his resettlement there, and he would be forced to languish for years in the camps before some other country would approve of his repatriation. “All I would have to look forward to is more waiting, hoping and dreaming.”

His ploy was uncovered, however, when American officials cross-referenced the visa application that his sister had made previously to the U.S. She had included information about their brothers in France. So once again Bounlieng was forced to think and act instinctively. He told the American officials they had never sent him any money while he was at Nong Khai and Nopho, so he no longer considered them his brothers. Of course, that was not true, but the interviewers bought his story, stamped his, his son’s and his uncle’s visas and they were all free men.

Actual freedom came only after another six months in what Bounlieng referred to as a “much better camp” on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines. There they went through the acculturation process, learned American customs and studied English. “When I left Bataan, my thoughts were, `No more trouble. I’m on my way to America now. I’m safe from communism.’”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR — Marc Yablonka is a military journalist and author. His work has appeared in the U.S. Military’s Stars and Stripes, Army Times, Air Force Times, American Veteran, Vietnam magazine, Airways, Military Heritage, Soldier of Fortune and many other publications. He is the author of Distant War: Recollections of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, Tears Across the Mekong, Vietnam Bao Chi: Warriors of Word and Film, and Hot Mics and TV Lights: The American Forces Vietnam Network.

Marc from 2001-2008 served as a Public Affairs Officer, CWO-2, with the 40th Infantry Division Support Brigade and Installation Support Group, California State Military Reserve, Joint Forces Training Base, Los Alamitos, California, where he wrote articles and took photographs in support of Soldiers who were mobilizing for and demobilizing from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.

His work was published in Soldiers, official magazine of the United States Army, Grizzly, magazine of the California National Guard, the Blade, magazine of the 63rd Regional Readiness Command-U.S. Army Reserves, Hawaii Army Weekly, and Army Magazine, magazine of the Association of the U.S. Army.

Marc’s decorations include the California National Guard Medal of Merit, California National Guard Service Ribbon, and California National Guard Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf. He also served two tours of duty with the Sar El Unit of the Israeli Defense Forces and holds the Master’s of Professional Writing degree earned from the University of Southern California.

Leave A Comment