An excerpt from

A War of Their Own

FULRO: The other National Liberation Front, Vietnam 1955–1975

By William H. Chickering

A War of Their Own—FULRO: The Other National Liberation Front, Vietnam 1955-75; published by Casemate, pages 152-163, used with permission.

Nguyen Huu An, the North Vietnamese general at the battle of Ia Drang (p. 128), had come to the conclusion there was a way to nullify the American advantage in air mobility.

By drawing the Americans into a forested area with only a few places for helicopters to land—unlike the Ia Drang valley, which had been savannah—he could construct traps at the most likely places. He envisaged attacking a Special Forces camp first, causing an American infantry division to respond, then leading the division down a daisy chain of small battles by seeming to retreat until, in a clearing he had prepared near the border, the Americans would leapfrog to block the North Vietnamese from reaching their sanctuary in Cambodia. At that point, hidden antiaircraft guns would blast the helicopters out of the sky, and his troops could annihilate any Americans left alive. (“Annihilate” (tiêu diệt) was the word used in North Vietnamese Army (NVA) mission orders. Hanoi saw early that US resolve would dwindle with every American killed. Hanoi’s highest military award was the “Hero Killer of Americans Medal.” Achillean rage, killing 20, garnered a First-Class ribbon. Though the word “annihilate” could also mean “wound, capture, cause to desert, or even send fleeing from battle1, in practice it meant kill, and that included executing the wounded.)2

Nguyen Huu An decided on the Plei Trap Valley.

He and his staff had spent months personally walking the terrain, identifying and numbering likely landing zones, deciding whether each would be a killing zone itself or a gateway to a fortified ambush some distance away. For killing zones, he ordered pits dug to hide antiaircraft machine guns on tall tripods, with bullets as thick and heavy as the butt of an Altamont pool cue. The largest clearing had 12 pits within it, beneath straw mats, placed downwind so as to target the choppers’ underbellies when they lilted up to land.3

The general was acutely aware the Americans had 24-hour photographic surveillance from high altitude, not simply from the daily buzz of low-flying aircraft, so he insisted no leaves be allowed to wither above his hidden roads, no streams be muddied even briefly, and nothing edged or straight or pale leap from the dark holes below to strike American eyes. As the time for his trap approached, he ordered the laying of dummy telephone wire and the construction of a dummy footbridge to misdirect the Americans.

He was confident his men had a psychological edge over American soldiers, which he attributed to “superior morale and politics.” He was probably right. Convinced their country’s survival depended on expelling the Americans, they had an advantage in that most terrible of combat, hand-to-hand. In turn, hand-to-hand combat was crucial because the general had deduced one other thing from Ia Drang—that the only way to escape the ripping metal and roasting petrol dropped from airplanes was to “grip the Americans’ belt,” closing as rapidly as possible with the GIs, literally throwing themselves forward into one-on-one combat.

In the coming battle, he was sure that earth would defeat sky.

He probably did not give much thought to the Americans’ Montagnard troops, whom he referred to as “puppet commandos.”

On the morning of November 8, 1966, almost exactly one year after Ia Drang, 160 Jarai soldiers of the Mike Force were suited up and lounging back against their packs in loose formation on Pleiku’s runway. Despite their relaxed pose, every man felt a tension inside that wound tighter as the helicopters began their start-up process.

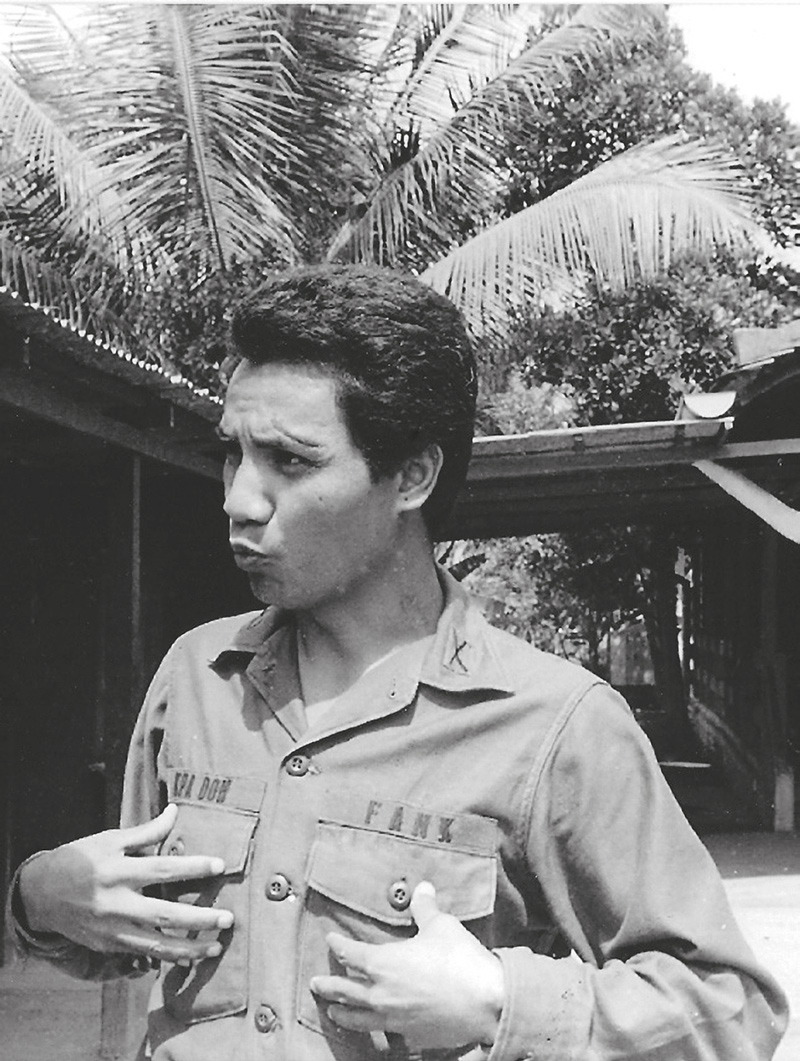

Moving among them in the billowing red dust was Kpa Doh, half-smiling but deadly serious, checking their equipment, himself bullous with grenades and pouches. As chief interpreter, he had no military rank, but his military experience was at least on a par with the Montagnard company officers, if not greater, having spent three years going out on patrols with Americans.

By virtue of his FULRO rank, he was the company’s political officer, essentially its commissar because the Mike Force was almost 100-percent FULRO. Every pay day, he would circulate, collecting everyone’s FULRO dues, one-tenth of their pay. (All Montagnard CIDG camps had a significant proportion of FULRO members, but the Mike Force units—Pleiku and Project Omega—had the highest numbers because they contained no Vietnamese at all.)4

Left to right, Kpa Doh, Y-Bham Enuol, and Nay Luett (Photo by CPT Crews McCulloch)

The Vietnamese Security Police accepted this situation, because it made the troublemakers easier to watch, and sent them all more often into the jungle, where they were less likely to infect other Montagnards with their ideas and more likely to die. The police knew Kpa Doh had been instrumental in the Second Rebellion and would have liked to quietly kill him, but when he took refuge in the Mike Force, they sat back to let the enemy do it for them.

He had just informed the soldiers of their mission, going into the Plei Trap, which they all knew was occupied by North Vietnamese. Some even had relatives there who worked for the occupiers as bearers. But what Kpa Doh told them was even more ominous, that they would be moving along the flank of the American 4th Infantry Division, wedged between it and the border. They would be first to make contact with the enemy, at which point they had to stay alive long enough to bring in the airplanes or American soldiers from the division. In other words, they were bait.

The six American Green Berets were their link to the sky, to its life-saving bombs or artillery shells directed onto the enemy, not onto them. However, they had heard this was sometimes an impossible distinction. (Indeed, four months later, Kpa Doh and the Pleiku Mike Force went out on an operation during which 14 Jarai and one American were killed by an errant US bomb.)

Whatever inchoate motivations the young Montagnards had—Jarai warrior tradition or hatred of Vietnamese or loyalty to comrades—they must also have had something higher to make them go out repeatedly on such dangerous operations, with no end in sight. It is reasonable to assume this was FULRO-related, either dutiful (gaining combat experience), or patriotic (preparing for their Final Battle with the Vietnamese), or both.

Passing over the massif below, the Jarai shuddered as cold, pure air whipped through helicopter doors, open for the machine guns. Raised in hamlets with no machines more complicated than manual water pumps, they had gotten used to this bounding, bird-like flight in no time, or casually pretended they had, but were happy to return to warm, moist air as the choppers dropped back down to skim the treetops. A brown, frothy river flashed by below, then strobing glimpses into the jungle’s depths.

In the distance to the north, razor-crested mountains marked the border with Cambodia. In the flatlands to the west—where they were heading—the border was anyone’s guess. As a dividing line, a figment of some Frenchman’s imagination long ago, it had been irrelevant until war came along.

The choppers slowed to circle a clearing below. A forest-covered hill jutted up just to the north. It showed no reflections of sunlight through its leaves, but the landing zone itself certainly had a North Vietnamese watcher, who would have stayed long enough to see the first choppers disgorge six Montagnards and two Americans each, then hurry to report the arrival of “commandos.” The sight of these small, dark men, with grins and gold teeth, and armed to within an ounce of staggering, cannot have been reassuring to him.

The whump-whump of choppers faded to blood’s thudding in the ears. One of the Americans was exhibiting signs of excess adrenaline. Kpa Doh kept ostentatiously calm to protect his Jarai from contagion.

The morning was still cool. This was the beginning of tropical winter when dryness plays the same role as dying light at higher latitudes. As they set out, chinks of clear blue sky were visible through the canopy far above. There was little undergrowth. They moved quickly to get away from the landing zone. Behind them, they heard the clatter of another two units of CIDG arriving, who headed off in a different direction, then silence.

General Nguyen Huu An would have learned by radio within minutes of their landing. But the successive arrival of more units at the same landing zone was too many for watchers to track. The Mike Force left without being followed. A rear guard, put out by the Jarai, made sure.

Over the next half hour, the forest began to drowse. Nearing midday, bird calls ceased. The point man—the most experienced Montagnard, chosen by the Jarai themselves—needed no instructions to slow down. Move, stop, and listen. Move, then stop, then listen. The pauses grew longer as the heat suffocated sound.

Kpa Doh (Courtesy of William Chickering)

The point man froze as he came round a large tree.

Those behind him knew instantly that he had enemy in front. For long seconds, no one breathed, then the point man ducked as he jerked his rifle up to begin firing. The first three Montagnards scrambled forward to join him. The tremendous noise went on and on, then diminished to scattered popping—shots being fired back by escaping enemy—then silence.

In a depression below was one dead soldier amid a large number of packs and helmets and parts of antiaircraft guns, and blood trails leading up the other side. Following the blood, they found more gun parts and eventually assembled three antiaircraft guns and their tripods.

The dead man had no rank or insignia but was much bigger than the average Vietnamese, thus likely a Chinese artillery advisor. The fact that he was killed outright, but none of the others were, was hard to explain unless he had tricked the point man into giving him time to get off a first shot himself—perhaps their eyes had met for an instant then, with superhuman self-control, he had kept his eyes sweeping the jungle foliage. This had bought him only a few more seconds of life but saved the others.

First blood was a shock, as was the battle roar that had ripped the midday heat. Until now, they could hope the Plei Trap was empty, but the presence of an antiaircraft detachment meant a very large number of North Vietnamese was somewhere around, perhaps 2,000 men. Even the Montagnards guessed this and were unnerved. Kpa Doh’s remedy was to put on one of the NVA helmets and stroll about as though nothing had happened. As he came around a tree, the hyped-up American almost shot him.

Awareness of the beast jumped a notch two hours later when they found its lair, a wide area of bamboo huts with sleeping platforms and classrooms, even a small firing range—all ringed by foxholes. Despite the gloom of late afternoon, deepened by a forest canopy purposefully woven overhead, the bamboo had the gleam of recent construction. The lieutenant decided to spend the night, taking advantage of the defenses, setting out Claymores, explosives that spray shrapnel in one direction on detonation by signal down a wire.

Three of the Americans brought out a deck of cards and played Hearts until dark, a calming thing to do, at least for those calm enough already. Kpa Doh watched them intently, occasionally asking questions as to the rules. (On subsequent Mike Force operations, some Jarai played Hearts too.)

Night was the worst. The North Vietnamese preferred to attack at dawn. They would maneuver as close as possible to American lines after nightfall, during the forest’s slow-building frenzy of creature calls. Scouts would crawl in first to cut the Claymore wires, then unspool telephone wire back out to guide them back with their comrades. Then they would wait in the hours of dead silence after midnight, to attack in a rush at daybreak.

Sometimes, but not tonight, the two sides could smell each other in the moist air. Americans thought the Vietnamese smelled like wet clothes. The Montagnards claimed they could tell North Vietnamese by their sickness smell, from malaria and/or months on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Bothersome to all were the mosquitoes wafting in the air around midnight. Unknown to any of them, Anopheles was making blood brothers of men about to kill each other.5

Close to the equator, the sun drops like a rock and daylight comes up with a rush. Americans were poor at gauging this, but the Montagnards knew exactly when to get ready. If any American still slept, they nudged him awake in the last black hour.

Along the backbone of Southeast Asia, it got cold overnight. Men shivered as they watched the blackness slip away between the trees. But no attack came.

The next morning they set off west toward the Cambodia border, about five miles away. Undergrowth thickened, slowing progress. The point man would drop to the ground from time to time to peer beneath the brush ahead. More worrisome, the canopy overhead was thickening too. Their sky was disappearing, which meant that, if they met a large enemy force, they could not count on bombing because it required visual contact through the canopy.

By now, the general knew exactly where the Mike Force was, and sometime after noon, they started catching glimpses of small groups of North Vietnamese in the distance, eerily motionless, looking right at them. If anyone went in pursuit, the watchers would disappear.

They rested that night on a knoll, again setting out listeners who were instructed to pull back in if any strange noise occurred, a cluck or mournful cry, something that did not belong in the cacophony after dark. They again set out Claymores, like shotguns primed with lead nuggets, but they waited until it was too dark to be seen doing this. The Americans had been issued Dexedrine, to stay awake. No one needed it.

Unknown to them, the general had given orders to ignore them for the time being, to be ready instead for an American infantry battalion that would arrive any time now, about two miles away. At one prominent clearing, the crews of 12 camouflaged antiaircraft guns had been waiting for a full month, sitting at the bottom of earthen pits. Positioned just across the border to pounce on the arriving division were soldiers of the 88th Regiment.

Y-Bham Enoul, a French-educated Rhade civil servant, was the president and commanding general of FULRO. (Courtesy of William Chickering)

However, word had failed to filter down to every North Vietnamese soldier that there was a company of “Saigon puppet-army commandos” out there in the forest, stealthier than the American infantry. The next day, two Vietnamese were captured. Grilled by a Vietnamese-speaking Jarai, one prisoner revealed he had been told Americans would cut his head off and eat his remains.

With no blood paid yet, Americans might have felt the bill mounting. But Kpa Doh and his Jarai could not have thought in those terms. Their war had no scales, no clocks, no substitutes running in from the sidelines. Their enemy would never cease taking over the highlands unless violently stopped. If they ever allowed themselves to imagine the day their war would be over, the span of time stretching out before them had only one metric—the number of enemy they could kill—just like the North Vietnamese.

General Nguyen Huu An had guessed right. A battalion of the American 4th Infantry Division did airlift the next day into one of the areas he had prepared.

However, by pure chance, the lead helicopter pilot chose to land in a clearing adjacent to the one with the antiaircraft guns, one that was brushy and uneven, letting his troops off at a 10-foot hover instead of settling down. No ground troops were killed during the landing, though three gunships were shot down. The Americans headed to a low hill 1½ miles northeast of the Mike Force and started to dig in.

The next night, after an hour-long 120 mm mortar barrage, the 2nd Battalion of the 88th NVA Regiment breasted through head-high thorn bushes to attack the low hill, some reaching the Americans’ foxholes to leap in with bayonets.

Surprisingly, the final count of US casualties in this battle was a low five killed, 41 wounded (not counting the helicopter crews).

The Plei Trap operation was Bob Ramsey’s first combat experience, at age 26. Despite that, he found himself calm, which he attributes to extensive prior training. “Kpa Doh was the same way,” he said, “Too busy thinking, taking everything in.” (For both of them, however, it was more likely innate.)

The following is based on Bob’s account, with contributions by Jake, the lieutenant.6 It picks up the story on the fourth day.

They are still moving west toward the border. By midafternoon, they see light ahead through the trees—a large clearing. (General Nguyen Huu An had chosen not to include this clearing in his plan, possibly because it was so close to the border that the Americans would never use it as a major landing zone.)7

They hold back, sending out small patrols to reconnoiter around its edges. Bob takes one to the right, around the northern end,8 keeping the white shimmer to his left. The forest is triple canopy, thus with little undergrowth, and visibility is good, as far as 50 yards. The sun is still high enough for sunlight to filter through. At one point, he sees two motionless North Vietnamese scouts’ watching them. When the scouts finally move, seen through the trees, they flicker.

Coming around the northern tip, he finds a dirt road coming out of Cambodia, wide enough for vehicles. He then continues his recon down the western side of the lakebed, returning by the same route to report to Jake. The road looks certain to be used. Jake wants Bob to set up an ambush there, but not until after dark. In the waning light of afternoon, Bob retraces his steps to decide on a position, taking key Jarai with him (but not Kpa Doh, who is with Jake).

Because they are being watched, the only possibility for deception is to change location when it is pitch black. Sometime after 7:00 pm, with only a sliver of waning moon in the west and clouds blotting the stars, Bob takes 50 men straight across the bare hardpan of the lake to the location scouted earlier, where they put out Claymores facing the road. He tells the Montagnards that a red flare will be his signal to withdraw straight back across the lakebed. Otherwise, they need little instruction, certainly not in ambushes. Bob sits with his back against a tree, certain something is going to happen, and begins a very long night.

Meanwhile, Jake and the main body of the Mike Force, with Kpa Doh, move further away from Bob, down the eastern edge of the lakebed and set up their perimeter, a semicircle looking out into the forest. Tactically and psychologically, the open space and sky at their backs belong to them and the forest belongs to the North Vietnamese, especially when Jake learns, on a radio call to preregister artillery support, that they are now out of range. So, no artillery, just air.

Sometime after midnight, the Montagnards break out shouting—a violent, startling cacophony—then stop, their bellows echoing into the forest. One of the men heard or smelled the enemy. The usual reaction would be to fire into the night, but the men were sending a message more important than bullets: “We dare you to attack. We are Jarai.”

As daylight creeps through the trees, Jake feels, then hears, the distant drone of the forward air controller (FAC) and raises its pilot on the radio. (A small, vulnerable airplane that flits and swoops, the FAC is a crucial intercessor between earth and sky if troops get in trouble, by directing airstrikes.) The pilot asks for help determining their exact location, as there are one or two other clearings in the area. Jake begins directing him to the correct lakebed. It is about 6:00 am.

Bob had been watching the road appear out of the night, as if the remainder of his fated life—short or long—were in a film bath.

Montagnard troops in formation, 3rd Company, Pleiku Mike Force, 1966 (Courtesy of SGM Robert Ramsey)

Suddenly, firing breaks out to his front. It is from the men furthest forward at his listening post, then from the rest of his troops. In the gray light, he can make out enemy in a column of three coming from Cambodia. They had begun scattering and dropping when he fired the Claymores, and, in his mind’s eye forever, he sees more of them fall like bowling pins. They begin returning fire. Its volume grows, and he realizes there are more enemy than he thought (later he figures out this was a weapons platoon, with mortars, preparing to set up at the northern end of the lakebed). He fires the red flare, yelling for his men to withdraw. The North Vietnamese fire a red flare, too, which results in their ceasing fire, then pulling back. This makes no sense—unless two red flares meant “withdraw” to them. Their temporary mistake gives his group time to get across 200 yards of dangerously open ground. Last to cross, he helps one Jarai who has been hit. Bullets are kicking up dust around them as they reach the tree line.

Meanwhile, Jake is on the radio to the FAC when he hears Bob’s explosions and the rattle of gunfire. Less than a minute later, his own perimeter is attacked. The North Vietnamese had been out there in the forest all night, waiting to attack, when Bob’s encounter forced their hand. They are only coming from the south, suggesting they did not have time to encircle him. The first wave of attackers comes in a ragged rank toward the ring of Jarai, who are belly down on the ground in pairs, firing from behind small trees.

The Montagnards have been trained to fire one bullet at a time, but rapidly, aiming at the enemies’ legs because their carbines kick upward. Some do just that, some fire wildly on automatic, and a few do not fire at all, paralyzed. Out of some perverse pride—mirroring the Americans, or perhaps it was the other way around—the Montagnards are not dug in and have no helmets, which costs some their lives, but the North Vietnamese tend to fire high which saves many others. With time, gaps appear in the defensive line as Montagnards are killed or wounded. In the din, they yell to each other. Even the simplest of men grasp quickly what it takes to survive and, from time to time, someone rises to a crouch and moves to fill in.

For their part, the North Vietnamese have been trained to throw themselves forward—to hug the Americans’ belt—to avoid the napalm and bombs sure to come behind them. They have been told the Americans will cower like rabbits, but it is unlikely many believe that, plus they know they are also facing Jarai. They do know that the faster they attack and encircle their enemy, the better their chances of survival. Some are impelled as well by hatred of the invaders. But the rifle fire is more deadly than expected, and the Mike Force has two .30-caliber machine guns. One stops firing early, but the other puts up a murderous wall across the front of half the perimeter until it stops abruptly—there are shouts in Jarai and one brave soul stands up to change barrels (the other barrel having grown too hot)—then resumes fire.

The first attack seems confused and hesitant. Jake has the sense of enemy “just moving around” to his front. Eventually, the North Vietnamese withdraw. They have lost the advantage of surprise, and the minutes are ticking down until the American planes arrive.

By attacking from a different direction, they might still derive some advantage, and this is probably what delays their second attack.

Meanwhile, Bob has been making his way south just inside the treeline toward the sounds of battle. His men having preceded him, he is alone, in brushy forest, and beginning to think that all enemy are further south when he comes across a dead Jarai in dark, black-striped fatigues, glistening with blood.

Montagnard troops (Courtesy of SGM Robert Ramsey)

Suddenly two Vietnamese in khaki emerge in front of him. They are sideways to him, but one begins to turn. He shoots both dead with his carbine only half up from the hip. Shortly afterward, he comes across a Vietnamese crawling, with his pants down at his knees “as though gut-shot”—wounded in the abdomen. Their eyes meet. Bob lets him go and keeps moving south, joining the northeastern part of the Mike Force perimeter.

Around 7:30 am, the first airplanes arrive, propeller-driven Skyraiders, ground-attack aircraft from the Korean War that drop napalm and cluster bombs, the latter loosing a stream of bomblets that explode on large branches, showering shrapnel in a rolling wave. For now, it kills only North Vietnamese on the other side of the lakebed.

Mortar rounds start landing near the Mike Force position, the hollow sound of their tube-launches coming from the northern end of the lakebed. Jake and a Montagnard step out of the tree line to fire grenades toward the mortars, and the mortaring stops. Meanwhile, the Americans have guessed the size of the North Vietnamese force—almost four times their own number—and are beginning to worry about running out of ammunition.

A second attack begins, now from the east. Bob takes cover behind a large log, with a nearby eight-foot hedge. Down the line he can see the lone machine gun, already with a large number of enemy dead to its front, not quite a pile yet but two North Vietnamese are using the corpses as cover. One throws a Chinese potato-masher grenade that fails to explode. The attackers come crouching at a trot, screaming, an inhuman sound. Bullets crack in the branches. Trees splinter. Leaves rain. To Bob, it is like the roaring approach of a giant lawnmower. He sees a rocket-propelled grenade zipping toward him for a half-second before hitting a nearby tree with a deafening explosion that blows him several feet to the ground. Again, the enemy’s attack slows, many now firing from behind nearby trees or on their bellies. He can hear their officers urging them onward in high-pitched voices. He begins lofting grenades over the top of the hedge at concentrations of them. This has the added advantage of killing without giving away his own position. He has eight grenades; when he runs out, he scuttles to collect more from dead Jarai.

On the radio with the FAC, Jake calls for an airstrike “danger close.” When he gets it, some hot fragments strike within the Mike Force perimeter. The FAC needs to know better where they are. Jake steps out from the tree line to throw two colored smoke canisters onto the lakebed. Suddenly, he feels as though a baseball bat hits him full force in the abdomen, dropping him. He cannot move his legs. Under fire, Bob and another sergeant drag him to a safer location.

Around 8:00 am, jets arrive with 500-pound bombs that blast whole trees into the air a second after their screaming runs. This only makes the enemy’s attempt to get close more insistent, with attacks coming from the east, then the north.

However, now the FAC knows exactly where the Mike Force is located. Skyraiders can strafe close to its perimeter with 20 mm cannon, shells that explode on impact and light fires, adding to the haze. The Mike Force reports 50 percent casualties over the radio and requests reinforcements and more ammunition.

In the distance, Bob sees Kpa Doh moving upright through the smoke, which looks first to Bob as if he has lost his mind. Then he realizes Kpa Doh is walking behind a line of his men, probably reminding them to aim low or to save ammunition, or maybe steadying them because they have become agitated by how close the bombing is getting. A couple of them already have minor wounds from hot fragments.

Suddenly, Kpa Doh shakes his head, as though stung by a wasp. Dropping his carbine, he tears off his web gear as if angry, throwing it to the ground. Then, after a pause, he picks up a big stick and resumes walking, tapping his men’s boots as he passes. He has been struck in the neck by an AK-47 bullet. Barely able to speak, he is letting his men know he is still there.

Bob cannot pinpoint exactly when this happened, except that the feeling there were enemy soldiers everywhere was lessening.

“It didn’t even knock him down,” Bob says. “It just looked like it pissed him off.”

Until I heard this, Kpa Doh had seemed inauthentic to me—a cultural hybrid out of place in a story about Montagnard agency. But this—this was 100 percent Jarai. News of it would have spread to Jarai and Rhadé everywhere, instantly raising his status within FULRO.

“His only armor was his heroism.”

Thus say the eroded words on a Cham stela from a thousand years ago, describing a forgotten king.9

The battle was essentially over by midmorning. Fourteen Jarai were killed, 40 were wounded, some badly, and got medevaced out around noon. Kpa Doh waited till last, then went out too.

Fifty-eight North Vietnamese were found dead, scattered about the battlefield. Some ten to twenty lay in front of the machine gun. Further out, some had been killed by airstrikes. Many others—dead or dying—had been dragged away by their comrades.

Elements of the American division began to arrive around noon, airlifting in a small bulldozer to dig a burial pit on the dry lakebed. There were so many North Vietnamese dead that they also brought in a front-end loader to carry their bodies.

Bob watched from a distance as it tipped the lifeless bodies into the pit, heads lolling, still gangly youth.

All six American Green Berets survived despite being in the thick of battle while one-third of the Mike Force Jarai were killed or wounded.

1. Merle Pribbenow, interview with author, November 28, 2017. click to return

2. As Merle Pribbenow pointed out to me, there is some irony in the fact that the North Vietnamese Army also had a body count. click to return

3. Phil Courts, “Shootout on the Cambodian Border,”, Vietnam Helicopter Pilots’ Association, at www.vhpa.org/stories/Shootout.pdf; and Phil Courts, interview with author, December 7, 2017. click to return

4. A sympathetic US master sergeant (Frank Quinn) knew about the dues because he stored the piastres in the unit safe until Kpa Doh made his next trip to Mondulkiri. That virtually all the Montagnard CIDG were FULRO was common knowledge, supported by Jim Morris (War Story (Boulder: Paladin Press, 1979), 21) and Y-Tlur Eban (interviews with author, 2009 onward) who quoted one FULRO leader (Phillipe Drouin) as boasting, “Any camp where there are Montagnards, these are our troops.” My own Project Omega Mike Force battalion was said to have been “rented” from FULRO. click to return

5. Some Jarai on this operation, with known (previously quantified) immunity to local Falciparum strains built up over a lifetime in the Central Highlands, nevertheless came down with acute malaria, either because the stress of combat temporarily weakened their immune system and thus allowed the malaria always lurking within them to escape immune control, or because they had been bitten by mosquitoes freshly laden with unfamiliar Falciparum strains from the Northern Highlands, i.e., picked up by the North Vietnamese on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and brought south. The timing of these cases’ onset tends to suggest the latter. Note: though Kpa Doh’s unit and its battle are not specifically named in the journal articles from which I extracted this information, it is clear they refer to the Pleiku Mike Force and its major operation in western II Corps in November 1966. Stephen C. Hembree, “Malaria Among the Civilian Irregular Defense Group During the Vietnam Conflict: An Account of a Major Outbreak,” Military Medicine 145 (1980), 751–52. click to return

6. The other three Americans were Frank Huff, Frank Quinn, and Danny Panfil. All three were equally important to the outcome of the battle, but I was unable to interview Frank Huff, killed in action five months later, or Frank Quinn, who was especially close to Kpa Doh and who died of natural causes in New York City only a few years ago. Danny Panfil preferred not to be interviewed. During the battle, Danny helped Bob drag the wounded Jake to safety under fire, and later, as a medic, worked to save Jake. Frank Huff was with Bob on the night ambush and then, during the battle, took over the radio, calling in airstrikes after Jake was wounded. click to return

7. No one is exactly sure today which clearing it was. Some believe it was bisected by the border. For unclear reasons, it was named “Pali Wali” by the Americans. click to return

8. The lakebed was roughly banana shaped and actually on a northeast–southwest slant, but I refer to “northern” end and “western” and “eastern” sides for clarity. click to return

9. Georges Maspero, The Champa Kingdom, translated by Walter E. J. Tips (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2002), 168. click to return

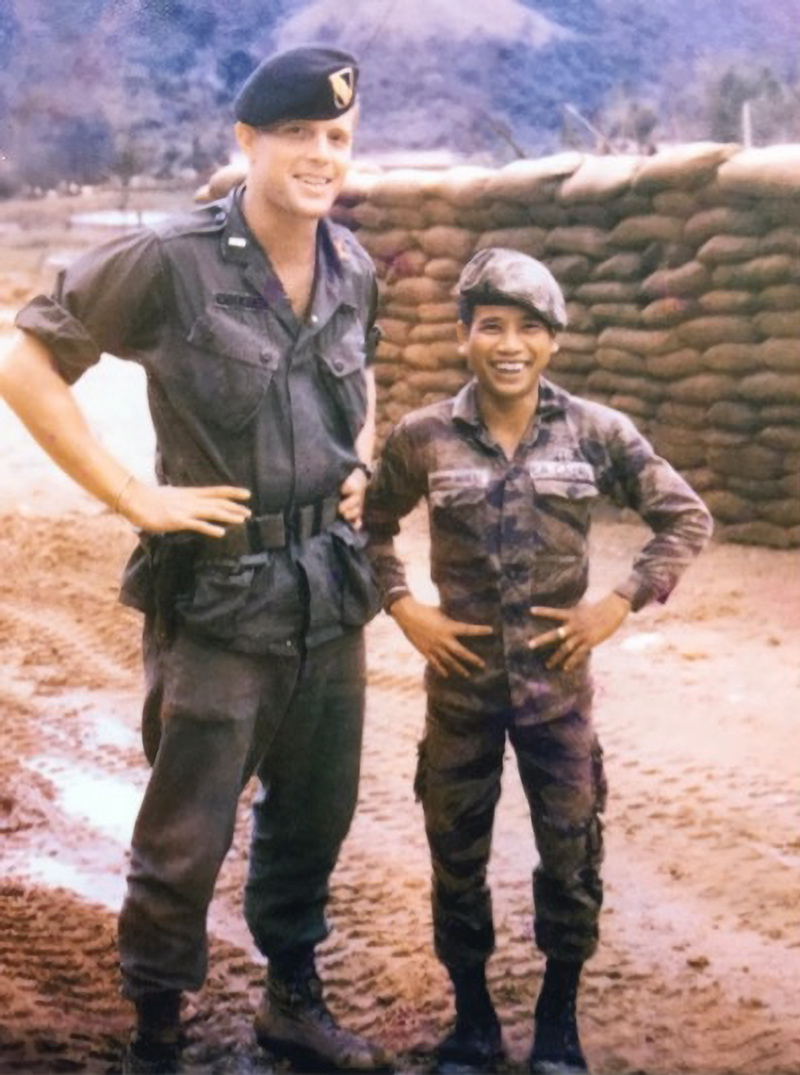

Author with Hre interpreter at Gia Vuc, Dinh-Nieu (Courtesy of William Chickering)

About the Author

William Chickering dropped out of Yale in 1963 to enlist in the paratroops. When Vietnam heated up, he became an officer, then joined Special Forces. After Vietnam, he went back to college, then medical school, subsequently working as a doctor in Korea, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, Cameroon, and China. He moved to Phnom Penh with his French wife and two children in 2012 to track down the story behind FULRO.

Leave A Comment